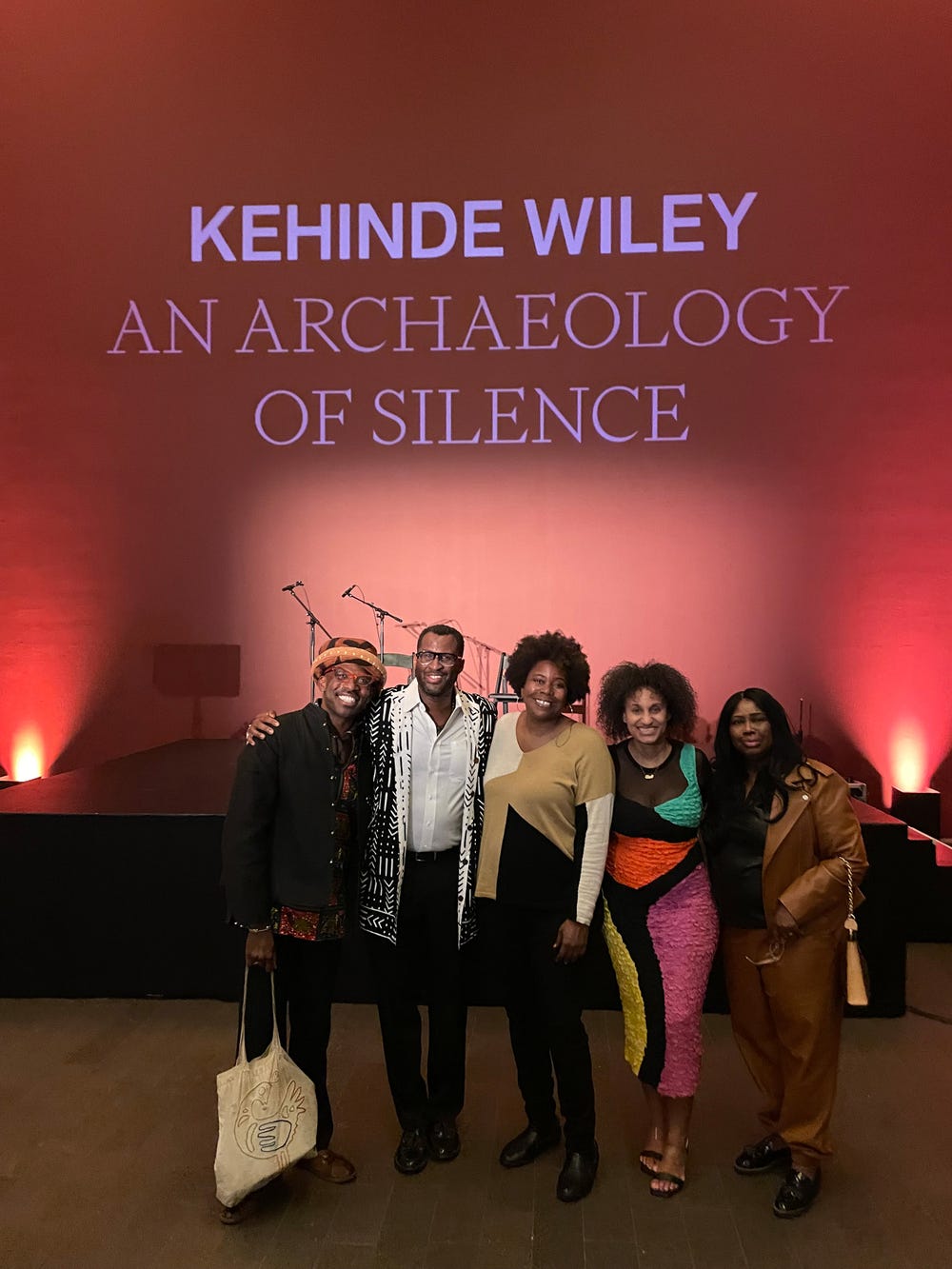

Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence at the de Young, 2023. Photograph by Gary Sexton

My role as the inaugural director of interpretation is to ensure we are telling the most inclusive stories to the broadest audience. I call this equitable interpretation. So far, this has meant reviewing wall texts and developing an interpretation partners program for special exhibitions whose themes are connected to the experiences of local communities.

My position came out of what is often framed as the racial reckoning of 2020, following the murder of George Floyd. While the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF) had already begun anti-racism work, like so many arts institutions, they felt a new urgency to address histories rooted in exclusion and white supremacy.

I consulted with FAMSF for three years prior to the creation of the director of interpretation position. I had the chance to peek behind the scenes at the Museums’ attempts to tell more inclusive, thoughtful, and meaningful stories. The experience affirmed what I perceived to be an unwavering truth: words matter. What might seem like simply replacing a word with a synonym could have a truly validating and instructive effect on our visitors. For two current exhibitions, Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence and Ansel Adams in Our Time, I collaborated with FAMSF staff and local community interpretation partners to create narratives that help guide and situate the exhibitions.

Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence

When it was suggested that the titular sculpture of the Kehinde Wiley exhibition be housed in the de Young’s main thoroughfare, Wilsey Court, my response was visceral. We needed an opt-in and opt-out for visitors and staff to mitigate potential harm to those impacted by systemic violence against Black people. The artworks, symbols of vulnerability and transcendence in the face of anti-Black racism, deserved an intentionality of care for Black visitors.

Installation view of Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence, de Young, 2023. Photograph by Gary Sexton

I knew I wanted interpretation partners to guide the way we framed this exhibition, so I contacted 20 local organizations working to dismantle systemic violence against Black and Brown people. I remember calling an organization focused on preventing youth violence; their executive director said she did not think they could support our effort because, “We don’t have the bandwidth, with all of the violence going on in Oakland.” This was a reminder to keep the people affected by the silence this work uncovers at the heart of the interpretation.

I was honored that seven people representing local organizations agreed to join this ministry of meaning. One partner is Reverend Wanda Johnson, the mother of Oscar Grant, the young Black man murdered by a Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) police officer at Oakland’s Fruitvale Station in 2009. As a Black man from the Bay Area, I often think about Oscar Grant, because his humanity was obscured by the color of his skin and in a moment his life was stolen.

Rev. Johnson and the other interpretation partners met with me, Claudia Schmuckli (the exhibition’s curator), and other FAMSF staff to consider Wiley’s work and the words most appropriate to describe the paintings and sculptures. The partners suggested important shifts in language, including changing “state-sanctioned violence” to “systemic violence,” “Black bodies” to “Black people,” and “victims” to “victims and survivors.” They wondered if this exhibition would exacerbate the fatigue on Black minds, hearts, and spirits given the prevalence of Black death in news media and popular culture. They also asked about how Black joy and resistance could be incorporated into the experience.

Interpretation partners at the de Young: André Bloodstone Singleton, Abram Jackson, Dr. Micia Mosely, Dr. Akilah Cadet, and Rev. Wanda Johnson. Photograph courtesy of Abram Jackson

Devin Malone, director of public programs and community engagement, suggested we create a respite room next to the exhibition and a resource room housing books and other information to support visitors afterward. The respite room includes note cards and a notebook for visitor reflections. The resource room offers a takeaway pamphlet with resources related to organizing, advocacy, grief, mental health, and political education. The resource room also includes texts that reflect the art historical references in Wiley’s work and contemporary sociopolitical works, like Tricia Hersey’s Rest Is Resistance and Breeshia Wade’s Grieving While Black. In addition, several interpretation partners contributed to our audio tour and web articles, which can be found on the exhibition web page. André Bloodstone Singleton, cofounder of The Very Black Project, often referred to our interpretation meetings as a virtual healing circle. This reminded me that, beyond telling an inclusive story, our time together was also an opportunity for a cohort of Black people impacted by systemic violence to heal through the medicinal powers of art.

Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence at the de Young, 2023. Photograph by Gary Sexton

Thanks in part to the Museums’ engagement with these community partners, Google.org agreed to become a sponsor partner for the exhibition, letting us offer eight free weekends (in addition to our Free Saturdays), free audio tours, a short documentary, additional community meetings and discussions, and coverage of the exhibition on Google Arts and Culture.

I recently ran into a young Black man in the galleries. He shared that he had not expected the exhibition to impact him in such a deeply emotional way. His eyes began to well up, and we held each other’s gazes, sharing an inner knowing and appreciation for a body of work and its interpretation that would hopefully allow us and many others to feel and heal.

Ansel Adams in Our Time

Under the leadership of Christina Hellmich, curator in charge of the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, and Hillary Olcott, associate curator of the arts of the Americas, the Museums have worked in consultation and partnership with Indigenous cultural consultants on our collections and exhibitions since 2015. Our 2021 Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo exhibition was co-presented with Pomo curators and cultural leaders Robert Geary, Sherrie Smith-Ferri, and Meyo Marrufo. Our recent Alaska Native Art project was developed in partnership with the Alaska Native Heritage Center and educators Lauren Ayagakuchax̂ Peters (Unangax̂) and Stephen Qacung Blanchett (Yup’ik). Given the sometimes-problematic collection and presentation of Indigenous objects in Western museums, Hellmich and Olcott are committed to shifting the power of who is telling the stories and what audiences might engage and learn from the Museums’ work.

This inclusive tradition is an important backdrop for the collaboration that ensued for Ansel Adams in Our Time. The exhibition originated at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and included consultation with Indigenous scholars from the Osage Nation, Nez Perce Tribe, and Dine / Navajo Nation. The consultants supported a more inclusive narrative about the presentations of Native American homelands and ancestors that are a huge part of Ansel Adams’s work.

Installation view of Ansel Adams in Our Time, de Young, 2023. Photograph by Randy Dodson

When we embarked on the interpretation planning for the Ansel Adams show, we noticed that Indigenous communities from the Southwest were not originally consulted about the images. Considering that Adams’s photographs include several Pueblo communities, we decided to reach out to Brian Vallo (Pueblo of Acoma), and Joseph “Woody” Aguilar (Pueblo of San Ildefonso). I worked closely with Hellmich in these efforts, as she established these relationships in her department’s work on a stewardship and publication plan for Pueblo pottery in the collection. In our virtual sessions with Vallo, Aguilar, and other Indigenous interpretation partners, we asked three important questions: 1) Is this photograph or object appropriate to display? 2) If so, is what is written about it appropriate? and 3) If not, what shifts in words, framing, or historical context is needed? What came out of our meetings were important shifts in language, like using “cultural observance” instead of “dance,” “vanquished people” instead of “vanishing race,” “ancestral pueblo” instead of “ancient ruins,” and “inhabited and stewarded” instead of just “inhabited.” Many considerations emphasized addressing ideologies of settler colonialism that informed the way Native people were represented and the misperceptions therein.

Ansel Adams (1902–1984), Indian Dance, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico, 1929. Gelatin silver print, framed: 17 1/8 x 21 1/8 x 1 in. (43.498 x 53.658 x 2.54 cm); image: 5 5/8 x 7 3/4 in. (14.288 x 19.685 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, The Lane Collection ©️ The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The “In the American Southwest” section of Ansel Adams in Our Time includes photographs taken by Adams at San Ildefonso Pueblo, Acoma Pueblo, Taos Pueblo, and Zuni Pueblo from 1927 to 1946. These four Pueblos are sovereign nations and federally recognized tribes. At one of our meetings, Aguilar looked closely at an image titled “Indian Dance” and exclaimed, “That’s my great-grandfather!” A collective gasp ensued — an ancestor in an image, from the time when many subjects were unnamed by photographers, had been identified. Not only that, but a descendant was present to speak about this ancestor’s legacy. Aguilar authored an extended label for the exhibition on the photograph and his great-grandfather: “This is a Cloud Dance (Po-Woh-Geh-Owingeh), and the person that is second from the right is my great-grandfather, Joe Aguilar. This cultural observance is a spring ceremony for special occasions where rain, the landscape, and cosmology are centered.” This instructional label is a powerful addition to our interpretation. While the photograph was taken at a time of uneven power relations between photographer and subject, the voice of a descendant provides new agency.

Another critical part of the exhibition was a “Take Action” resource guide. We wanted to ensure the list of resources centered opportunities to practice allyship with local Indigenous communities. Kanyon Sayers-Roods (Mutsun-Ohlone / Costanoan, California Indigenous Two-Spirit), founder of Kanyon Consulting, partnered with us on the categorization of opportunities and suggested specific opportunities for visitors inspired by the exhibition’s emphasis on environmentalism. The resource list also included suggestions from FAMSF staff and reflected a broad range of opportunities centered in local Indigenous allyship.

Looking forward

Interpretation speaks to the mission and vision of FAMSF in practical and profound ways. The creation of the director of interpretation role, in addition to our work with interpretation partners, is a wonderful moment in power shifting. It prepares a foundation for a 21st-century institution that is truly for all. From the shifting of words to the incorporation of community voices, equitable interpretation ensures our audiences have meaningful museum-going experiences. I am excited to see what is still to come in this important anti-racist approach to interpretation. The possibilities are endless, and I am ever so hopeful.

Text by Abram Jackson, director of interpretation.