Alaska Native Art

November 23, 2022

Welcome

This project was developed in partnership with the Alaska Native Heritage Center and educators Lauren Ayagakuchax̂ Peters (Unangax̂) and Stephen Qacung Blanchett (Yup’ik). It features the contributions of artists and cultural practitioners from across Alaska. We are grateful for each person’s participation and guidance: Qaĝaalakux̂, Quyana, Gunalchéesh, Haw’aa, Quyanaq, Thank you.

Welcome: We are Alaska

—Abel RyanLearning about art is . . . learning a new way, new language, almost. A new way of seeing the world . . . cultural education.

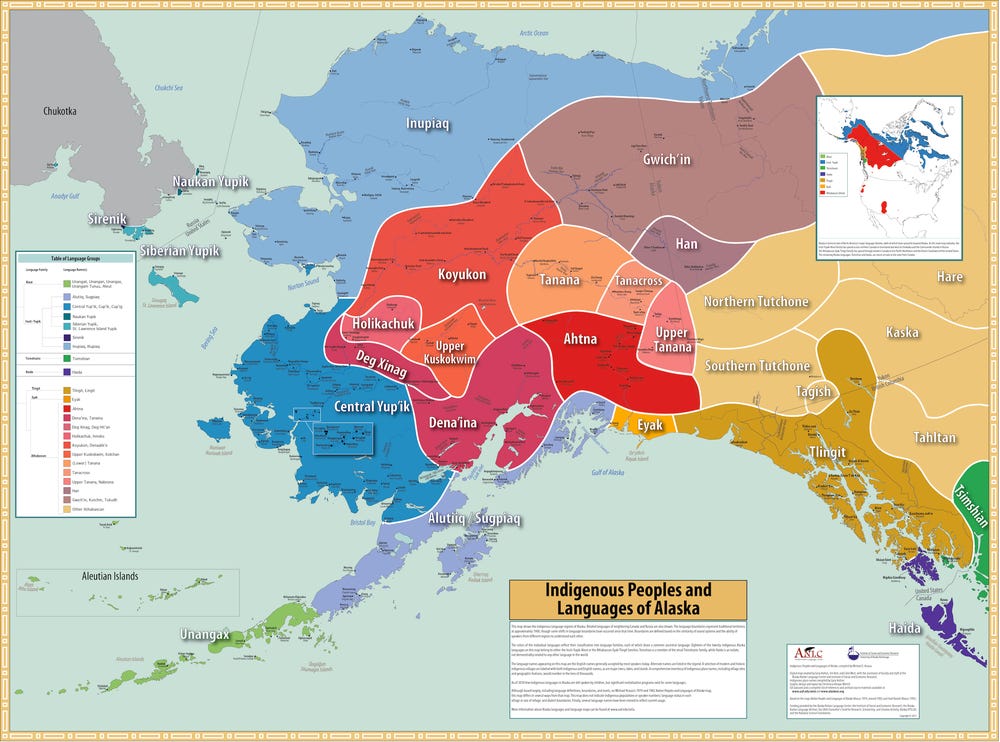

Alaska is the largest geographic state in the United States and encompasses over 660,000 square miles of diverse landscapes: oceans, mountains, forests, and tundra. It is the homeland of many Native peoples, whose ancestors have lived on and moved across the land since time immemorial.

Krauss, Michael, Gary Holton, Jim Kerr, and Colin T. West. 2011. Indigenous Peoples and Languages of Alaska. Fairbanks and Anchorage: Alaska Native Language Center and UAA Institute of Social and Economic Research. Online: https://www.uaf.edu/anla/collections/map/

As we look to Native communities in Alaska, we acknowledge the Indigenous peoples of the Bay Area. The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco are located on the ancestral homelands of the Ramaytush Ohlone. The greater Bay Area is the ancestral territory of the Miwok, Yokuts, and Patwin, as well as other Ohlone peoples. Indigenous peoples from many nations, including from communities in Alaska, make their home in this region today.

The artworks in this Close Look are united by cross-cultural themes: Family, Sustenance, Transportation, and Celebration. Each theme is introduced by a short film featuring cultural practitioners from different regions of Alaska. Their voices enliven the collection and connect historical objects to contemporary communities.

The themes are grounded in the Shared Values of Alaska Native Cultures and explore the importance of language, ecology, resiliency, and survivance across these topics. This is not a comprehensive survey of Alaska Native arts; it is an offering of an alternate interpretative framework.

Celebration: Dancing who we are (still), 2022. Produced in partnership with The Range

As you explore this Close Look, we invite you to draw connections between the films and historical works. We encourage you to be guided by questions rather than seek answers. We invite you to listen to others’ perspectives and reflect on how you uphold the values and beliefs of your own culture. How are these values and beliefs embodied in the artworks and objects around us? What can we learn by taking a Close Look?

Project team

Partners

Alaska Native Heritage Center

Advisors

Lauren Ayagakuchax̂ Peters (Unangax̂), PhD scholar, University of California, Davis

Stephen Qacung Blanchett (Yup’ik), cultural heritage manager, Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska

Collaborators

Paul Asicksik (Iñupiaq), community engagement manager, Alaska Native Heritage Center

Tara Bourdukofsky (Unangax̂), director of cultural and education services, Alaska Native Heritage Center

Yaari Walker (Saint Lawrence Island Yupik), community engagement manager, Alaska Native Heritage Center

FAMSF team

Hillary C. Olcott, associate curator, arts of the Americas

Emily Jennings, director of school and family programs

Magnolia Molcan, web managing editor

Patricia Buffa, director of digital strategy

Sheila Pressley, director of education

Christina Hellmich, curator in charge, arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas

Khamisi Norwood, digital media producer

Megan Bates, digital media producer

Hannah Freeman, senior teaching artist

Antonia Smith, web content coordinator

Film interviewees

Alvin Amason (Sugpiaq Alutiiq)

Stephen Qacung Blanchett (Yup’ik)

Louise Brady (Tlingit)

Perry Eaton (Sugpiaq Alutiiq)

Emily Edenshaw (Yup’ik / Iñupiaq)

Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit / Unangax̂)

Lily Hope (Tlingit)

Aaron Leggett (Dena’ina Athabascan)

Marie Arnaq Meade (Yup’ik)

Margaret Nakak (Iñupiaq / Yup’ik)

Abel Ryan (Tsimshian)

Haliehana Alaĝum Ayagaa Stepetin (Unangax̂)

Christopher Sumdum Jr. (Tlingit)

Yaari Walker (Saint Lawrence Island Yupik)

Andrew Weaver (Yup’ik)

Special thanks

Michele Trefon

Emily Edenshaw

Jaimeann Bell

Presley West

Alaska Native Heritage Center Native Games Team

Herring Rock Water Protectors

Thomas G. Fowler Education Fund

Katelyn Stiles

Jennifer Younger

Thomas Gamble

Courtney Fallow

Renee Villasenor

Randy Dodson

Robert Carswell

Family

Family: Connecting generations through art

Shared Values

Know Who You Are — You Are a Reflection on Your Family

Honor Your Elders — They Show You the Way in Life

—Abel RyanA lot of our designs have to do with our identities and our stories. . . . We use this art form to represent who we are as individuals but also who we are as a group.

Why do we wear what we wear? What do our clothes say about us, our families, our environments?

Clothing is often the first thing we notice about one another. It is a powerful tool of communication and speaks to our cultures, values, and backgrounds. This is even more true for ceremonial clothing, or regalia. Designs, passed down through generations, can be the intellectual property of communities or individuals — owned, maintained, and shared at the discretion of communities or leaders.

Haida artist, Hat, late 19th century. Spruce root and paint. 10 x 14 x 14 in. (25.4 x 35.6 x 35.6 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Estate of Mrs. Thomas B. Bishop, 54.76.6

How do we honor our forebears and share cultural pride?

Designs reflect family ties and broadcast who the wearer is and where they are from. The materials used speak to place — sourced from the environment and protecting the wearer from the elements that surround them. Chilkat style textiles, called naaxein in the Tlingit language, are made by weavers from the southeast region of Alaska.

—Lily HopeOur Chilkat blankets record history. They tell who we are as a people. They tell our clan stories, memorial stories . . . They’re really our written history before words were put on paper.

Tlingit or Haida. Chilkat blanket, mid 19th century. Mountain goat wool, cedar bark, dog fur, sinew, and thread. 51 x 64 in. (129.5 x 126.6 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Museum purchase and exchange, M.H. de Young Art Trust Fund, Simon Bibo Mercantile Company, Dr. Joseph Simms, H.H. Welsh, Mrs. Milton H. Esberg and the Henry J. Crocker Estate, by exchange. 72.38. Photograph by Randy Dodson

Tlingit or Haida. Chilkat blanket, mid 19th century. Mountain goat wool, cedar bark, dog fur, sinew, and thread. 51 x 64 in. (129.5 x 126.6 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Museum purchase and exchange, M.H. de Young Art Trust Fund, Simon Bibo Mercantile Company, Dr. Joseph Simms, H.H. Welsh, Mrs. Milton H. Esberg and the Henry J. Crocker Estate, by exchange. 72.38. Photograph by Randy Dodson

This atkuk (parka) was made by a skilled Saint Lawrence Island Yupik seamstress for a specific man in her life. The parka features family designs and the signs of its maker, communicating at a distance who the wearer was.

This atkuk (parka) is made from bird breast skins and trimmed in dog fur. The bird skins are lightweight and provide excellent insulation, making the parka ideal for hunting. Saint Lawrence Island Yupik. Man’s parka, early 20th century. Murre breasts, dog hair, seal skin, cotton, and bast fibers. 46 7/16 x 26 in. (118 x 66 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Percy L. Schoof, 47476. Photograph by Randy Dodson

Creating these garments and regalia requires a great deal of knowledge: harvesting the materials, processing them, and assembling them into a completed piece. This work is often planned and executed over months or even years.

Clothing designs speak to family ties, traditions, and stories. Their creation requires stewardship of knowledge, materials, designs, and the practices of making. This stewardship crosses generations, forging ties to ancestors while creating a legacy for future culture bearers.

Sustenance

Sustenance: Caring for ourselves and our environments

Shared Values

Live Carefully — What You Do Will Come Back to You

See Connections — All Things Are Related

—Haliehana StepetinEvery time we eat our Native foods, we say it makes our spirits full . . . Eating the foods that we’ve always eaten is a really deep connection to place. It invites all of these relationships that we have to sustain and maintain.

What knowledge is required to sustain oneself within an environment?

Those who practice subsistence lifestyles harvest food and resources from the environments around them — hunting birds and mammals, fishing, and gathering plants from the land and sea. They must know when and where to harvest resources, how to process them, and how to sustain them for the following seasons.

This ceremonial spoon is made of mountain goat horn. The handle is carved with clan designs. It may have been made as a gift for a member of the opposite moiety. Tlingit artist, Spoon, ca. 1880-1900. Mountain goat horn. 9 3/4 x 2 3/4 x TK (24.8 x 7 x TK cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Dr. H.W. Yemans, 6323.

This wooden spoon was intended for regular home use. It was made for and used by a specific person. The red and black painted designs mark it as a special object. Yup’ik artist, Spoon, ca. 1890. Wood and paint. 2 3/4 × 7 1/4 × 1 5/8 in. (7 × 18.4 × 4.1 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.217. Photograph by Randy Dodson

How do we nourish our bodies, minds, and souls?

A subsistence lifestyle instills mindfulness and respect for the environment but also for the community, the ancestors who shared their knowledge, and future generations of cultural stewards. Tools for harvesting, processing, and sharing food are often made with animal parts — bone, teeth, sinew, and horn — and are beautifully decorated.

—Yaari WalkerYou cannot take more than what you need. You must not waste. And you must share . . . As Alaska Native people, when we hunt and we gather, we try to utilize as much as we can.

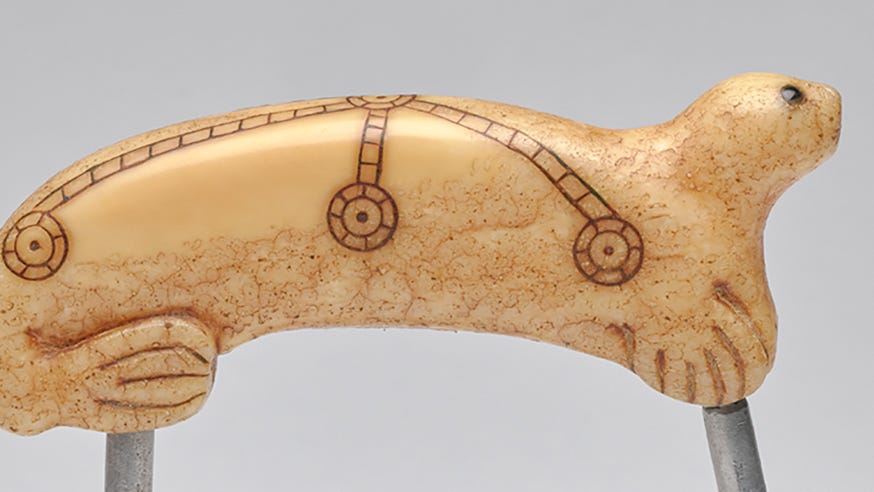

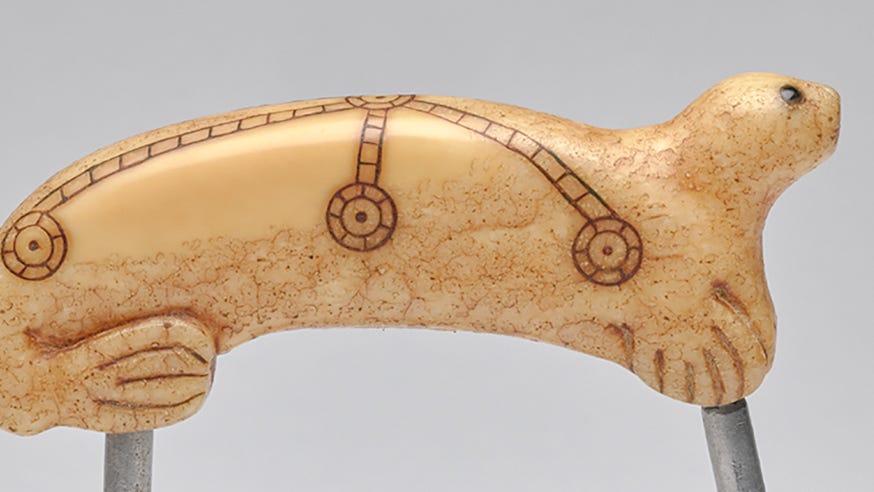

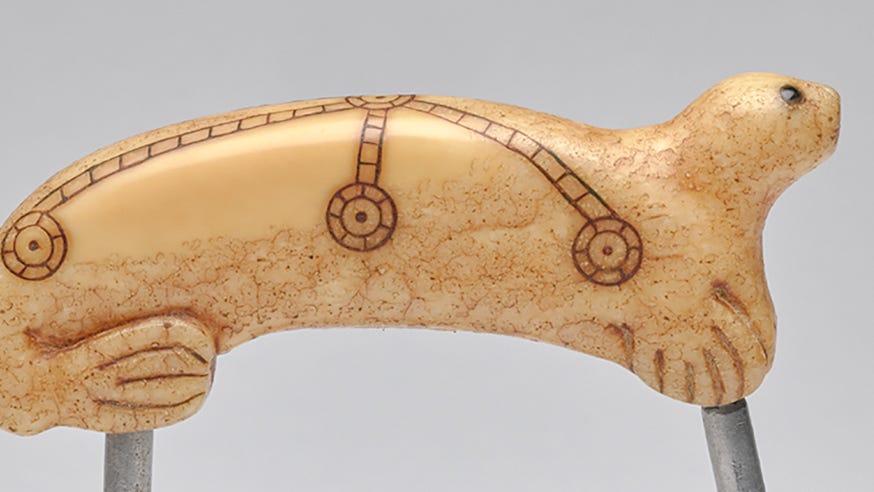

Hunters incorporate animal parts into their tools. This ice scratcher is made of seal claws attached to a wooden handle. Yup’ik artist, Ice scratcher, ca. 1880. Wood, seal claws, and sinew. 3 1/8 × 10 1/8 × 1 3/4 in. (7.9 × 25.7 × 4.5 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.228. Photograph by Randy Dodson

The handle is carved into a seal face to show respect for the animals who give their lives to sustain human communities.

This ice scratcher was made and used by a Yup’ik hunter. Ice seals use their teeth and claws to maintain breathing holes in frozen waters. They are attracted to the scratching noise of other seals, so a hunter would use this tool to attract potential prey.

Ulu refers to a semicircular blade with a handle. The term is derived from the Iñupiaq word uluuraq (woman’s knife), but this type of knife is used across Alaska.

Ulu handles are typically made of bone, walrus tusk, or wood. Blades vary in size and shape depending on the intended use. This technology is ancient and has changed little through time.

Cup’ig artist, Ulu, ca. 1890. Iron alloy, walrus tusk, and pigment. 51/4 × 71/4 × 5/8 in. (13.3 × 18.4 × 1.7 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.24. Photograph by Randy Dodson

How can we be more conscientious about our impact on the environment?

Despite generations of policies by the US and Canadian governments to remove Native peoples from their lands and restrict cultural practices, principles of subsistence living persist. Today, however, many communities’ livelihoods, resources, and activities are threatened by legislation, commercial fishing practices, and global warming. Food sovereignty is paramount for communities to protect their ability to sustain themselves and their environments.

Learn more

Can Indigenous subsistence rights still be protected in Alaska?

Legal efforts of Alaska Native communities to maintain subsistence living

How Alaska Native communities are building resilience to climate change

Impacts and responses to climate change within Native communities

Transportation

Transportation: Navigating the land and sea

Shared Values

Accept What Life Brings — You Cannot Control Many Things

Have Patience — Some Things Cannot Be Rushed

—Perry EatonWe look at water different than other people. You see patterns on the water . . . You read it. You literally read it.

What propels us to move?

Moving across the landscape is an integral part of life. We travel to procure food and supplies, to see loved ones and friends, to attend events. Alaska encompasses diverse terrains and environments change through the seasons; seas and marshes freeze in the winter, making distant locations easier or harder to reach.

Transportation: Navigating the Land and Sea (still), 2022. Produced in partnership with The Range

How do we move across the places we live? What sorts of knowledge and skills does this require?

With more than 66,000 miles of shore and a multitude of inland waterways, Alaska has the longest coastline of any state in the nation. Navigating it requires advanced technology and deep knowledge of weather, terrain, and necessary tools, as well as great stamina built through training and games.

Games like the high kick increase strength, coordination, and pain tolerance, training travelers to survive long distances and stave off hypothermia. Yup’ik artist, Ball, early 20th century. Hide. Dimensions TK. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mrs. Grace Wallace, 60.16.

—Nicholas GalaninEverything we do is connected to place.

In the southeast, Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, and other Pacific Northwest communities carve canoes from the trunks of cedar trees. Called yaakw in Tlingit, these boats vary in size, and, depending on the shape, can be used to navigate fresh water systems or open ocean.

(left) Like a full-sized boat, this model canoe is painted with clan designs. Haida artist, Model canoe, late 19th or early 20th century. Wood and paint. Dimensions TK. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Horace L. Crocker, 38319. (right) This model boat is painted with clan designs and also features carvings on the bow and stern. Tlingit artist, Model canoe, late 19th century or early 20th century. Wood and paint. 38 3/4 x 8 1/2 x TK in. (98.4 x 21.6 x TK cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Estate of Mrs. Thomas B. Bishop, 54.76.43.

Many boats are decorated with designs relating to the families, clans, and communities who make and use them. Designs relating to families and stories announce who the riders are as they approach other communities.

Many northern communities in Alaska use skin boats. Large, high-capacity crafts called umiaq (large skin boat in Inupiaq), are used by whale hunters in the far north and can be used as shelter when on land.

Iñupiaq artist, Model umiak, ca. 1880. Seal hide, caribou hide, wood, baleen, and paint, 8 × 34 × 10 in. (20.3 × 86.4 × 25.4 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.86. Photograph by Randy Dodson

Smaller watercraft are called kayaks, derived from the Yup’ik and Inupiaq word qayaq; in Unangam Tunuu this type of boat is called an iqyax. Traditional kayaks have wooden frames and animal-skin hulls. Each community makes different shapes, depending on the type of water that needs to be traversed. Kayaks are personalized, made to the proportions of the user, as are the tools.

Yup’ik artist, Model kayak, 1920–1950. Bone, walrus tusk, sea mammal intestine, wood, thread, and paint. 23/4 × 93/4 × 11/8 in. (7 × 24.8 × 2.9 cm) Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.372. Photograph by Randy Dodson

Communities are always on the move. In Alaska, expert navigation is required to cross great distances and negotiate dangerous weather. It involves the participation of many skilled makers, who help carve wood for boats and paddles, sew skins for cover and clothing, and share knowledge of navigation. All of this fosters a deep connection to place and is an expression of cultural practice and identity.

Learn more

A Qayaq to Carry Us

Video series on one community’s journey building a kayak

Traditional Transportation

Multigrade curriculum resources exploring the importance of kayaks

Northwest Coast Canoes

Exploration of the types, construction, and uses of canoes

Celebration

Celebration: Dancing who we are

Shared Values

Share what you have — Giving Makes You Richer

Accept What Life Brings — You Cannot Control Many Things

—Louise BradyThere is a reason why we have had ceremony for so long. Because it’s a very powerful way to build relationships . . . Celebration is relationship building and healing.

Why do we celebrate, and how? What roles do celebrations serve for individuals and within a community?

Ceremonies are opportunities to gather and share culture. They remember the past, mark the present, and look to the future. They allow us to witness changes in the lifecycle of a person: birth, naming, adulthood, marriage, death, and mourning. Celebrations mark the seasons and activities engaged in during those times. Some ceremonies are appropriate for everyone to see, while others are restricted to select groups. They can be means of sharing joy and sorrow, of engaging in prayer and remembrance.

Yup'ik drumming and dancing at AFN

How do we celebrate?

Different kinds of artists collaborate for celebrations: musicians drum and sing, dancers perform. Food for feasts is gathered, prepared, and shared; the act of gathering becomes part of the process of celebration. Regalia makers create ceremonial garments, masks, and accessories. The cycle of celebrations provides a rhythm to life.

Fans are used during dances by communities across Alaska. These contemporary fans are made of colored grass woven into the shape of puffin faces and trimmed with fur. Alice Smith (American, Cup’ig, active 20th c.). Dance fans, late 20th century. Sweetgrass, reindeer fur, and hide. 12 x 14 x 1/2 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.346.

This historic fan, carved with a human face, lost its original feathers. Yup’ik dancer and artist Chuna McIntyre designed a mount to add feathers so the fan is whole again. Yup’ik artist, Finger mask, ca. 1880. Wood, pigment, and glass beads with modern feathers. 4 3/4 x 3 1/4 x 1/2 in. [cm TK]. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.188. Photograph by Randy Dodson

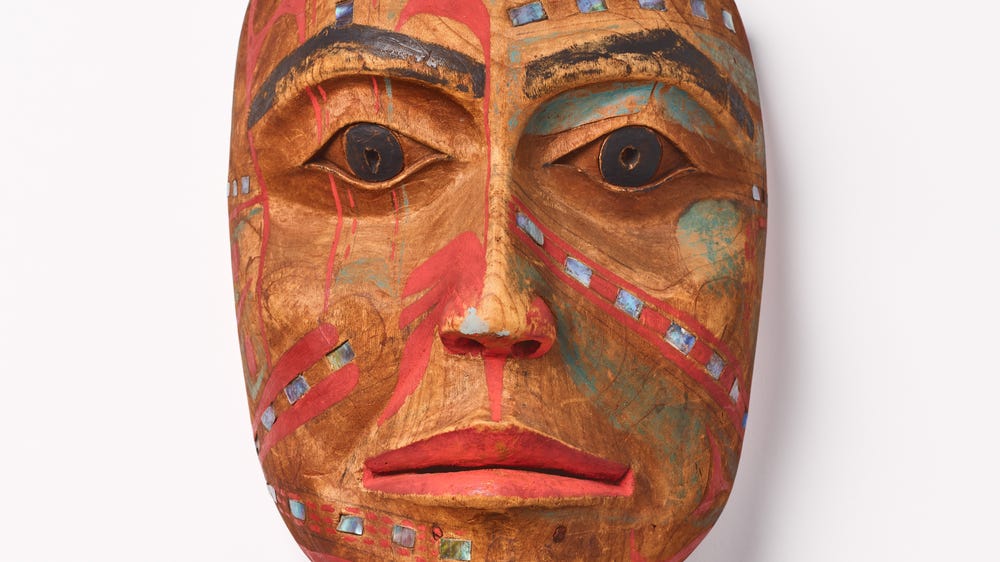

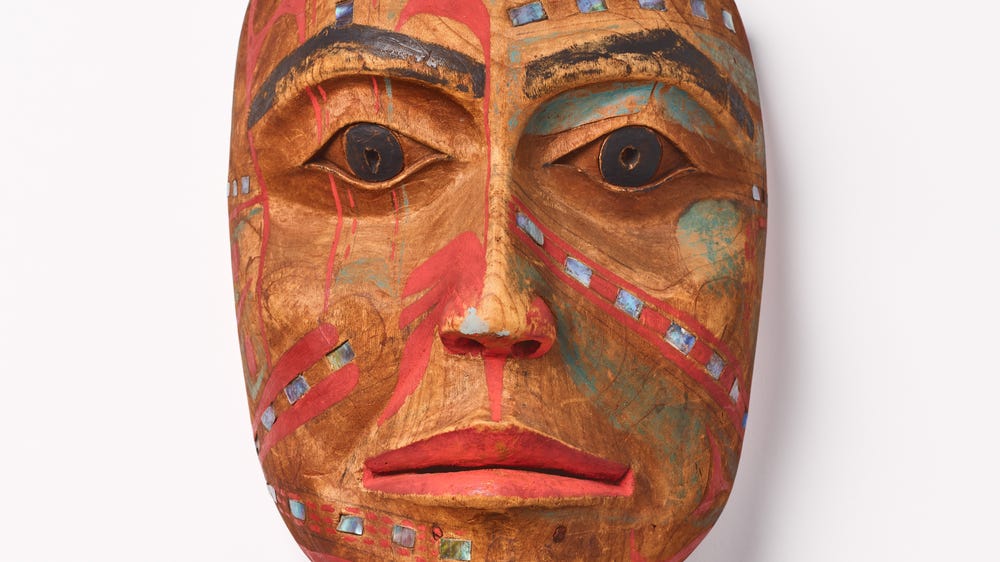

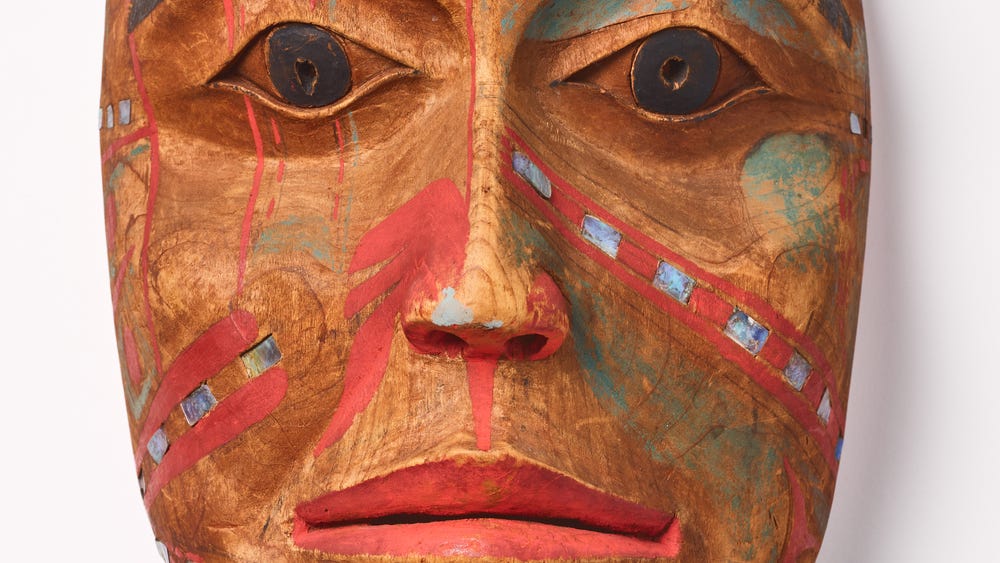

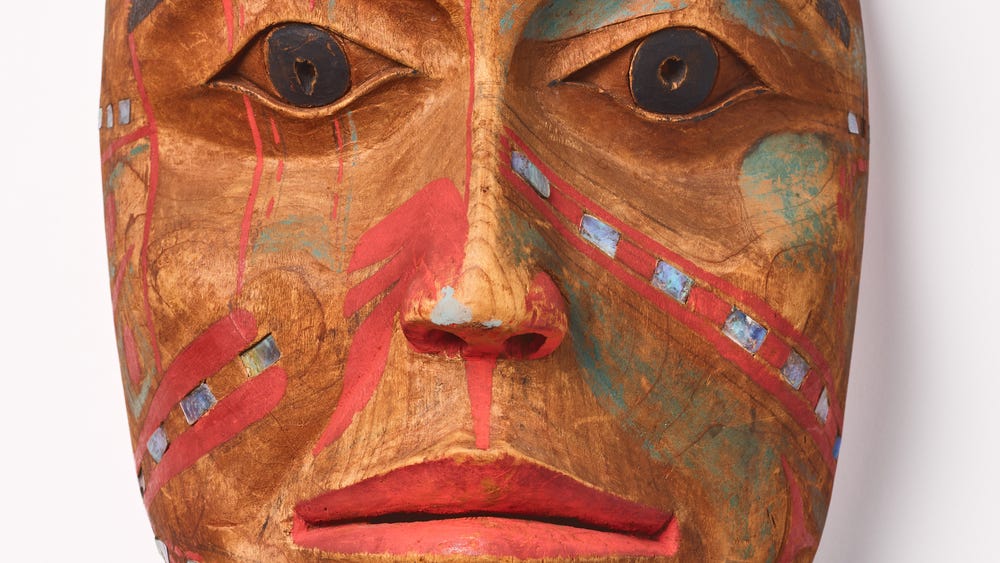

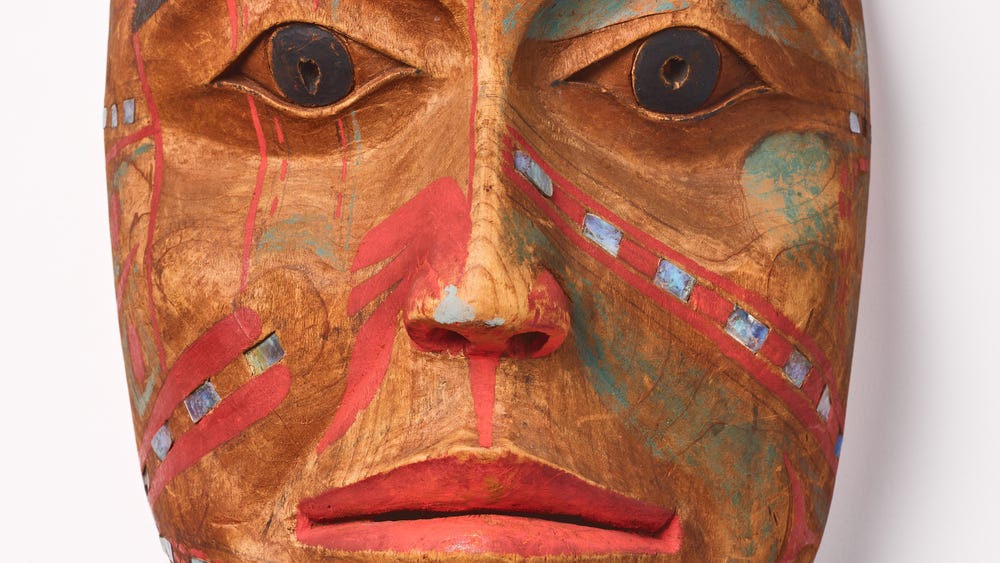

Regalia and other ceremonial objects may belong to a community, family, or individual. This mask was carved for a specific person who would have danced it in a public ceremony like a koo.éex’.

Tsimshian or Tlingit artist. Mask, ca. 1800–50. Wood, paint and abalone shell. 10 × 8 × 5 1/8 in. (25.5 × 20.5 × 13 cm). Gift of the Thomas W. Weisel Family to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2013.76.125. Photograph by Randy Dodson

The attendees were witnesses and validated the spiritual connection. They were paid for their participation so the exchange would be a balanced one.

These two masks from further north are related to ceremonies honoring the spirits of the animals that sustain human life. The celebrations are held in the winter and the dancers ask the animal spirits to return in the spring and offer their bodies to worthy hunters.

This is something that . . . went to sleep — I don’t like saying lost because . . . . . . that makes it sound like it’s permanent, but there’s no permanence, I don’t believe, in the colonization interruptions that we experienced.

—Haliehana Stepetin

Celebration is a powerful means of cultural expression and, for Native communities, survivance. In 1883, the US Congress passed the Religious Crimes Code and banned all Native ceremonies and dances. This followed a government policy to forcibly send Native children to Anglo-Christian boarding schools, separating families and disrupting cultural practices. It was not until 1978 that the American Indian Religious Freedom Act reinstated Native Americans’ rights to practice cultural rites and ceremonies. Today, celebration is an essential means of exercising religious freedom, strengthening communities, and reviving practices for future generations.

Learn more

History through a Native Lens

Timeline of historically traumatic events, settler-colonial policies, and Native resistance movements

Carved from the Heart

Exploration of how mutual support, art, and ceremony create paths to healing