Acquisitions of Contemporary Textiles from “The de Young Open”

By Jill D’Alessandro

March 25, 2021

For myself, The de Young Open was an incredible opportunity to be introduced to artists with whose work I was not already familiar. Through the exhibition, the costume textile arts department was able to make key acquisitions from two Bay Area artists, both of whom use the textile medium as a tool to address societal issues that impact our contemporary lives.

Fabric artist Alice Beasley has been exhibiting her work nationally and internationally for more than twenty years in solo, juried, and group shows, including exhibitions organized by the prominent African American Quilt Guild of Oakland, of which she is an active member. Beasley works both with store-bought printed fabrics and her own digitally printed fabrics and finds in them the colors, shadows, and textures she needs to create her subjects, by cutting the fabrics into small, organic shapes and piecing them together. A prolific artist, Beasley uses the quilt medium to create a breadth of work with subject matter that varies from still life to portraiture to family narratives, as well as pointed commentary on societal issues including politics, the environment, and the Black experience in the United States. In her work, Beasley draws upon the quilting tradition that she describes “to be one of the oldest forms of how women in particular showed and provided comfort to the people around them.”

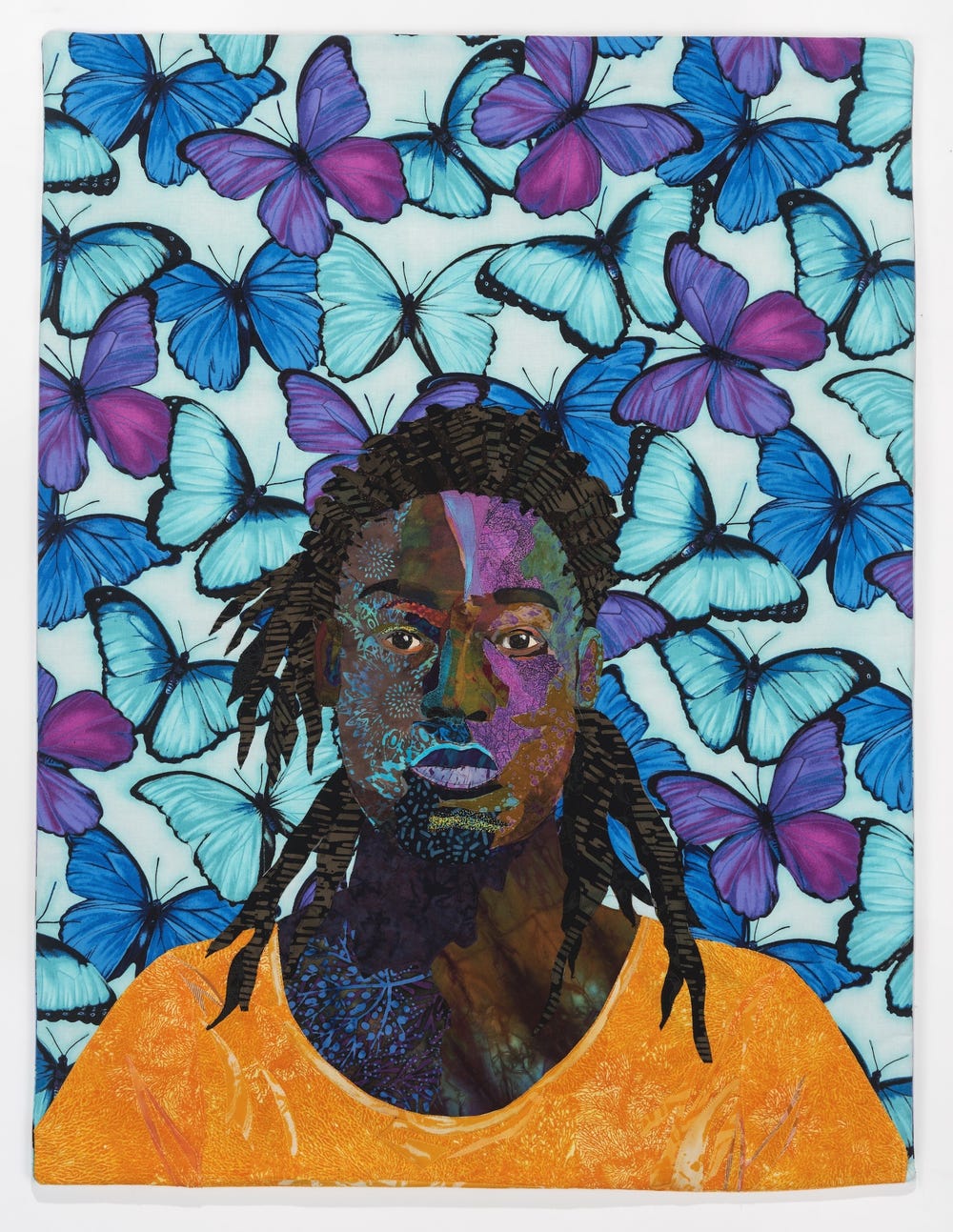

Alice M. Beasley (b. 1945), Floating Into the Heat of the Moon, 2019. Printed cotton; pieced, appliquéd, 32 1/2 x 24 1/2 in. (82.6 x 62.2 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Art Trust Fund, 2020.43.

Beasley is a former attorney who worked for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) legal defense fund, and approximately half of her work is political in nature. However, Floating Into the Heat of the Moon (above) was not intended to be political; it was simply meant to be a portrait of a young Black man, whom she envisioned in her mind. During The de Young Open panel discussion for our Virtual Wednesdays program, Beasley described her subject as having an “almost poetic, tender look with moonlight lighting his face and butterflies dancing above.” She intentionally gave him a neutral expression, inviting the viewer to create their own stories. Yet, cognizant of the current highly politicized climate surrounding the Black body, Beasley remarks: “Frankly, anytime you are showing the humanity of a Black man these days, you are necessarily entering into a narrative that requires a movement just to expound the simple proposition that Black lives matter.”

Watch D’Alessandro in conversation with textile artists here.

In the past few years, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco have acquired African American quilts from both the Souls Grown Deep Foundation and the Eli Leon Trust, which included the works of quilt makers such as Rosie Lee Tompkins, Arbie Williams, and Sherry Byrd. In a recent interview with the author, Byrd commented on the difference between the more traditional quilt makers, such as herself and her mother and grandmother, and “the younger, more modern generation of ‘East Bay Quilters’ who appeared on the scene after the Great Depression and WWII up to the present.” Byrd explains, “This generation appreciates and embraces the quilt as an artistic canvas or platform to express the inner depths of their souls. They want to not only create a beautiful ‘eye candy’ composition that captivates many. Their goal is twofold: First, they want and need to create beauty, but second, they also need to express and ‘tell’ stories, old and new that embrace individual and grouped feelings, hopes, dreams, trials, tribulations, and injustices, and the list goes on. They are brave pioneers in a new territory of the quilt/art making horizon.”

Beasley’s Floating Into the Heat of the Moon beautifully illustrates Byrd’s observations on the work of contemporary African American textile artists, and in doing so, enables the Museums to tell a richer and more complex story about African American quilt making traditions and the diversity of Black experiences.

Like Beasley’s, Sherwin Rio’s work offers the Museums a new vehicle for examining our permanent collection and allows us to better contextualize social and political issues through the use of personal narrative. Rio is an interdisciplinary artist who, as he articulates, “uses metaphors within a Filipino American lens to deflate systems of opposition and separation within cultural and historic convergences”. He is a graduate of San Francisco Art Institute, where in 2018, he received both the MFA Outstanding Graduate Award, and the Outstanding Graduate Award in New Genres, among many other achievements. As Rio explains, “My work often does this metaphorical positioning using the Filipinx and Filipinx-American framework to understand history, omission, to weave in family stories, imagine a more dignified and hopeful future, and tie in Southeast Asian proverbs that I grew up with.”

Sherwin Rio (b. 1992), SECOND GLOVES, 2019. Embroidered pineapple fiber (piña), 12 x 5 in. (30.5 x 12.7 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum Purchase, Art Trust Fund, 2020.44

SECOND GLOVES is from a series in which Rio reconfigured embroidered barong tagalog shirts, the national dress of the Philippines worn on formal and semi-informal occasions, into a pair of delicate and nonfunctional, or rather ineffectual, boxing gloves made of pina cloth. For Rio, SECOND GLOVES is a metaphor for the Filipinx-American fight for post-colonial visibility and agency. During the artist panel at Virtual Wednesdays, Rio shared his motivations in creating this body of work after moving to the Bay Area for graduate school. The series arose from Rio’s reflections on the West Coast struggle against orchestrated violence and oppression of Filipinx immigrant and migrant workers, while simultaneously contending with and critiquing the tropes of Filipinx nationalism and masculinity. He explains, “This work is a response to that [paradox], using the metaphor of boxing, which is an intricate, orchestrated, and studied kind of fight but at the same time sort of paradoxically deflating the instruments of the fight themselves.”

Rio’s intentional choice of pina cloth is noteworthy. Not only is it fragile, but it also serves as an emblem of the weighted history of colonialism in the Philippines. While the barong tagalog is today worn as national dress--a symbol of national identity—both the pineapple plant and embroidery were brought to the Philippines by European settlers, who introduced the cultivation of plants to be used as a natural fiber. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, embroidered pina cloth became a prized export good for the Philippines for markets in Europe and the United States, and workshops were established to train primary school children (both boys and girls) to create fine laces for the global market. Thus, SECOND GLOVES adds a new dimension and interpretation to the Museums’ existing collection of embroidered handkerchiefs and blouses from the nineteenth century.

The Bay Area has been a vibrant center for the textile arts since the 1940s. This was made evident in the strength of the textile artworks represented in The de Young Open, and I am pleased to have these extraordinary examples join our permanent collection as a testament to the public exhibition.

Text by Jill D'Alessandro, Curator in Charge of Costume and Textile Arts

Unfortunately, the de Young had to close its doors to the public again only six weeks into the run of The de Young Open. Learn more about how our staff organized the exhibition, and explore some of the artworks acquired from it. We are thrilled to announce our intentions of making The de Young Open a triennial event.