Thornton Dial, Lost Cows, 2000 – 2001. Cow skeletons, steel, golf bag, golf ball, mirrors, enamel, and Splash Zone compound, 76.5 x 91 x 52 in. Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio, Rockford, IL / Art Resource, NY. © Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Revelations: Art from the African American South

Revelations: Art from the African American South celebrates the debut of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco major acquisition from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation in Atlanta of 62 works by contemporary African American artists from the Southern United States.

Included in the current acquisition are paintings, sculptures, drawings, and quilts by 22 acclaimed artists, including Thornton Dial, Ralph Griffin, Bessie Harvey, Lonnie Holley, Joe Light, Ronald Lockett, Joe Minter, Jessie T. Pettway, Mary T. Smith, Mose Tolliver, Annie Mae Young, and Purvis Young. The history of the partnership between the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and the Souls Grown Deep Foundation dates back to 2006, when the Museums hosted the loan exhibition The Quilts of Gee’s Bend.

The cultural origins of these artworks can be traced back to the African Diaspora, slavery, and the Jim Crow era of institutionalized racism, which restricted both physical freedom and freedom of expression for African Americans. Despite these barriers, in the segregated and comparatively safe spaces of churches and cemeteries, as well as in the fields and forests, African Americans created a cultural language that led to the evolution of distinctly African American musical forms such as gospel, blues, jazz, and rock ‘n’ roll.

These rich musical traditions were paralleled by visual traditions that typically were symbolic in form or concealed from view in order to escape censure or destruction. Working with little or no formal training, and often employing cast-off objects and unconventional materials, these artists have created visually compelling works that address some of the most profound and persistent issues in American society, including race, class, gender, and religion.

Only during the modern civil rights movement did these visual traditions and their messages move into the open — initially in the private yards of African American homes, and later in commercial galleries and public museums. Historically marginalized, patronized, or promoted with reductive terms such as folk, naive, or outsider, these artists have earned equal consideration in the history of American art. Put in the context of the larger American Art collection at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the works — which include some of the finest contemporary art created in the United States—have the potential to influence American cultural studies to more accurately reflect the nation’s historical diversity and complexity.

A companion exhibition, drawn entirely from the recently acquired Paulson Fontaine Press archives, will also feature prints by Lonnie Holley, as well as four quilters centered around Gee’s Bend, Alabama — Louisiana Bendolph, Mary Lee Bendolph, Loretta Bennett, and Loretta Pettway.

In depth

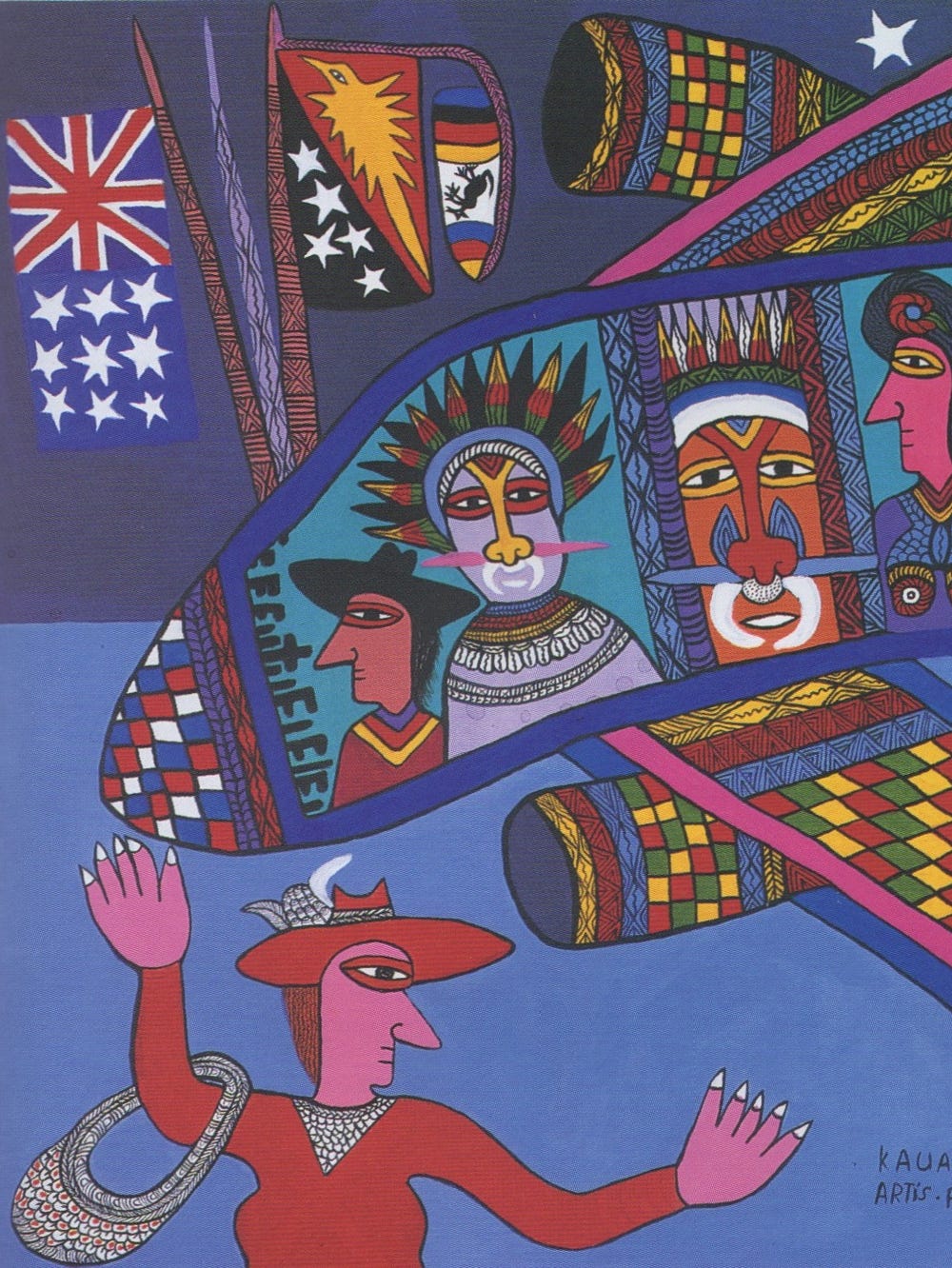

The introductory gallery will include a group of press photographs that document pivotal events in the Civil Rights movement, including the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama; the 1964 murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner; and the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King in Memphis, Tennessee. The last gallery will include works representative of a pan-African sensibility in contemporary art, including: African American artist Robert Colescott’s A Taste of Gumbo (1990), which depicts a white woman sampling black food and culture; Ghanaian artist El Anatsui’s Hovor II (2004), which uses recycled aluminum bottle caps to comment on post-colonial economic and cultural exchange; and British artist Cornelia Parker’s Anti-Mass (2005), created from the timbers of an African American Southern Baptist church burned by arsonists.

Acquisition Highlights

Thornton Dial (1928 – 2016)

“Art is like a bright star up ahead in the darkness of the world. It can lead peoples through the darkness and help them from being afraid of the darkness. Art is a guide for every person who is looking for something.” – Thornton Dial

Dial — whose life encompassed the institutionalized racism of Jim Crow, the modern civil rights movement, and the first African American president — is the most acclaimed artist represented in the collection. Dial began making art after losing his job as a steelworker in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1981. His ambitious artworks address a panoramic array of issues spanning from African American experience in the South to the events of 9/11 and America’s war in Iraq. His works have been included in solo exhibitions at the New Museum of Contemporary Art (1993); the American Folk Art Museum (1993); the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2005); and the Indianapolis Museum of Art (2011), as well as numerous group exhibitions, including the Whitney Biennial (2000).

Dial’s sculpture Lost Cows (2000 – 2001), created with painted skeletons of cows, ostensibly addresses the cycles of life and death that are critical to rural agrarian life. The abstracted skeleton behind the four white cows struggles to guide his wayward herd. As the title Lost Cows suggests, the sculpture critiques the supposedly superior white supremacists (represented by pelvic bones that resemble Ku Klux Klan masks) that created the Jim Crow system, while simultaneously becoming dependent upon — and “lost” without — the African Americans who worked as nannies, servants, maids, cooks, drivers, and caddies (represented by a white golf bag).

Lonnie Holley (b. 1950)

“My thing as an artist, I am not doing anything but still ringing that Liberty Bell, ding, ding, ding, on the shorelines of independence. Isn’t that beautiful? Can you hear the bell I’m ringing? And will you come running?” – Lonnie Holley

The 1979 death of Holley’s niece and nephew in a house fire led him to carve their tombstones, which marked the beginning of his career as an artist in Birmingham, Alabama. Holley combines the most pedestrian of recycled materials to create visual stories — often linking the past to the present — that are intended to teach and to inspire. His work has been included in solo exhibitions at the Birmingham Museum of Art (2003) and the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, College of Charleston (2015).

Holley’s assemblage Him and Her Hold the Root (1994), the artist’s most iconic and striking work, is comprised of a smaller “female” rocking chair that rests its “arm” upon a larger “male” chair, as if mirroring the supportive and stabilizing relationship of an absent female/male couple. Together, they support a large, anthropomorphic tree root with a “trunk” and “limbs” that recalls both family tree genealogies and the preservation of oral history and traditions through the generations. The composition clearly references elders remembering their roots, but it also subtly suggests that a younger generation is in danger of forgetting — or ignoring — its past.

Ronald Lockett (1965 – 1998)

“I don’t think I’ll be here when I’m 60, so I want to prove to people that I can succeed in what my dream was.” – Ronald Lockett

Lockett, the cousin of Thornton Dial, lived in Bessemer, Alabama, and inherited from his uncle and mentor a belief in the political and social power of art. His works, many fabricated from sheet-metal siding, focus on both timeless themes of life, death, and rebirth, as well as contemporary political and social issues, including nuclear destruction, domestic terrorism, civil rights, and the degradation of the environment. Lockett’s works — all created in the decade before his death at 32 from complications of HIV/AIDS — were recently featured in a major retrospective exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum (2016).

Lockett’s sheet-metal assemblage England’s Rose (1997) was inspired by the death of Princess Diana, who was among the first public figures to physically embrace people living with HIV/AIDS. The vertical bars recall both the vertical fence of Kensington Palace that was inundated with floral bouquets and the public’s perception that Diana was “imprisoned” by her role in the royal family. The gradual but inexorable descent of the rose bouquets from vivid life and light at the upper left into death and darkness at the lower right would have had special resonance for Lockett, who died the year after the work was completed.

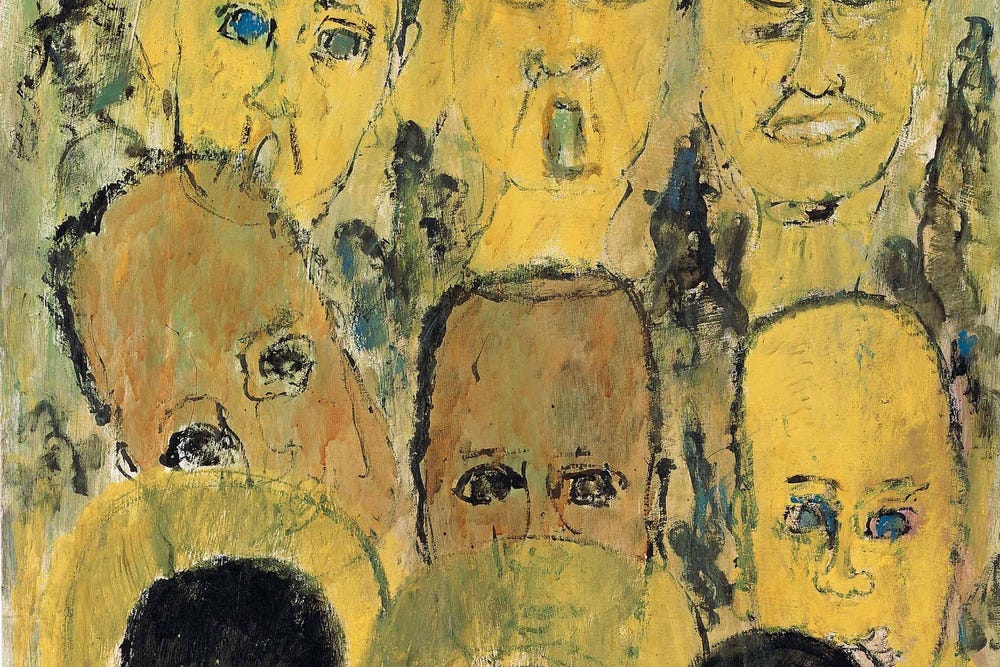

Purvis Young (1943 – 2010)

“In all the poverty, the crime, the pushin’ drugs, there is love. There is help. There is a change.” – Purvis Young

Young first turned to art while imprisoned as a teenager, when he began reading art books. Following his release in 1964, he was inspired by the example of the Black Arts movement, which advocated for politically engaged works that addressed African American experience. In the late 1960s Young’s Overtown Miami neighborhood rapidly declined into poverty and crime after the completion of Interstate 95 deprived the community of street traffic and consumers. Young sought sanctuary in the then-vacant “Goodbread Alley,” where he installed hundreds of mural paintings in an outdoor public gallery that documented both the harsh realities of life in Overtown, and his belief in divine intervention.

Young’s oil painting Talking to the System (ca. 1975), depicts three righteous young people, two of them with beatific halos, confronting four white and two black elders. The painting pays tribute to the essential role played by young African Americans — some of them martyred — in confronting systematic and institutionalized racism through the civil rights and black power movements of the 1960s and 1970s. At the same time, Young’s painting speaks to the perennial tension between older and younger generations, a dynamic that transcends race.

Ralph Griffin (1925 – 1992)

“I feel just like the astronauts exploring up there [on Poplar Root Branch stream]: I just want to see what I can find in these roots and things.” – Ralph Griffin

Griffin began making art around 1978 and is best known for creating sculptures from driftwood branches and roots that he retrieved from “Poplar Root Branch” stream near his home in Girard, Georgia. He asserted, “There’s a miracle in that water, running across them logs since the flood of Noah.” Griffin prized roots that appeared to have great age and “deep feeling,” and responded intuitively to the shapes and subjects that they suggested, saying that he “put a bit of vision on the root.” His root sculptures also evoke associations with the famous black conjure root, John the Conqueror, said to have talismanic and magical properties.

Griffin’s Noah’s Ark (ca. 1980), his most important wood assemblage, is based on the biblical account of Noah, who is instructed by God to build an ark for his family and a sampling of all the world’s creatures prior to the deluge. Griffin’s extraordinary conception of the Genesis story appears to conflate the blue waters of the flood, the white sky, the blood red of the flesh destroyed in the deluge, and the black mountain where the ark came to rest in one abstracted, boat-shaped form. For Griffin, the apocalyptic associations of Noah’s ark may have foreshadowed the equally cataclysmic slave ships that carried their human cargo across the Atlantic Ocean from Africa to America.

Joe Light (1934 – 2005)

“I think I have the answers to a lot of things from my experience. I work at trying now to just better my life. . . Everything is to the light.” – Joe Light

The redemptive messages of Light’s art were shaped by a delinquent adolescence, two prison terms, and a religious conversion in which he found spiritual guidance in traditional Jewish teachings. Light drew inspiration for his art from the Old Testament, and saw himself as a modern-day Moses exhorting viewers to adhere to moral standards of conduct in order to achieve spiritual salvation. Around 1975 he began painting both sacred and profane images to critique hypocrisy and injustice, but also to cultivate understanding and truth, exhibiting them publicly on and around his house in Memphis, Tennessee.

Light’s oil painting Dawn (1988) appears at first glance to be an indecipherable jumble of the calligraphic forms that the artist termed “Abraham’s writing,” after the biblical patriarch. Closer examination reveals the inverted and reversed phrase God of Israel, a personal declaration of devotion and a public proclamation of the path to spiritual salvation. The painting illustrates the Exodus story of the Israelites who flee slavery in Egypt for freedom in Canaan. Pursued by the Egyptian pharaoh and his army, Moses parts the Red Sea with his staff, enabling his people to cross on the dry land (symbolized by the flowers), while walls of blue water tower over him on either side.

Joe Minter (b. 1943)

“The way you make an African a slave, you make him invisible. I’m making the African visible.” – Joe Minter

Minter’s service in the U.S. Army combined with later jobs in metalworking, auto mechanics, and construction, proved ideal for his work as an artist, which he commenced in 1979. Minter’s yard in Birmingham, Alabama, which he calls the “African Village in America,” seeks to restore communal culture and pride, and is the most famous “yard show” in the American South. This outdoor museum tells the rich history of Africans and African Americans, with representations of African warriors, slave ships, segregated buses, Martin Luther King’s Birmingham jail cell, and grave markers for the four young girls killed in the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham (then known as “Bombingham”).

Minter’s welded metal sculpture Camel at the Water Hole (1995) is one of his “message pieces,” which are related to his “African Village in America,” but also serve as autonomous statements about African American history. Created from pick axes and shovels, this abstracted construction critiques the exploitative history of slavery and Jim Crow racism, which treated African American workers as “beasts of burden” akin to camels. As Minter notes, “My African ancestors built America on the sweat of their backs, in their blood, in their life — free slave labor — and the only pay is death.”

Reviews

Stories

Film

Special guests Lonnie Holley, Danny Glover, Paul Arnett, and Delroy Lindo comment on "Revelations: Art from the African American South."

Gallery

Sponsors

Director’s Circle: Diane B. Wilsey. President’s Circle: The Honorable Willie L. Brown, Jr., Belva Davis and William Moore, Denise Bradley-Tyson and Bernard J. Tyson, Paul A. Violich. Curator’s Circle: Sharon Bell and Karen Bell Francois and Family, Dr. Ronald and Mrs. Rosemarie Clark, Jill Cowan and Stephen Davis, Joyce and Al Dixon, Jr., David Fraze and Gary Loeb, Allison Nicholas Metz, MD and Family, Brenda Wright, California Hawaii State NAACP. Conservator’s Circle: Jeana Toney and Boris Putanec. Benefactor’s Circle: Cheryl Algee and Steven Eugene Davis, Ernest A. Bates, MD, Megan Bourne, in appreciation of Belva Davis, Tracy and Damon Burris and Family, Supervisor Malia Cohen and Warren A. Pulley, Francee Covington, Sterling A. Davis and Darolyn D. Davis, Frankie and Maxwell Gillette, Anette Harris and Marc Loupé, George and Marie Hecksher, Mauree Jane and Mark Perry, Sarah Ogilvie, PhD and Jane Shaw, PhD, Barbra Ruffin-Boston, Deborah Sims, Ed.D., Angelique and Irving Frank Tompkins, The San Francisco Chapter of The Links, Incorporated, Anonymous.