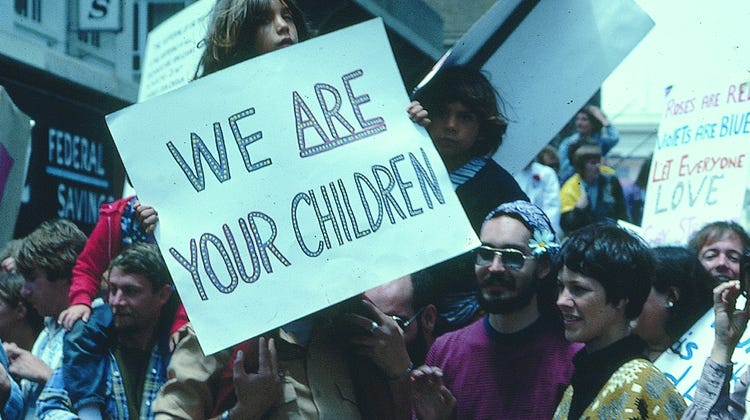

Participants march in the 1977 San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade. Photograph by Crawford Barton, Crawford Barton Papers (1993–11), GLBT Historical Society

In the first half of this year, more than 450 anti-LGBTQ bills have been introduced in legislatures across the United States. Some would prohibit trans kids from accessing vital health-care services, sports teams, or even the bathroom. Others would prohibit teachers from discussing LGBTQ history in schools, or force them to break the trust of their students by outing them against their will. Still others would ban Pride flags and drag performances. All of them attempt to shove LGBTQ people, our culture, and our history back into the closet.

As the new leader of the GLBT Historical Society, I am deeply troubled by the increasingly violent ideology attempting to erase the rights and lives of LGBTQ people, particularly women and people of color, throughout our country. I am committed to using every resource at our disposal to fight back for our future.

Participants march in the 1977 San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade. Photograph by Crawford Barton, Crawford Barton Papers (1993–11), GLBT Historical Society

According to a recent survey, just knowing a trans person significantly increases the likelihood that someone opposes anti-trans legislation. Exposure to the simple reality of queer existence is one of the most powerful antidotes we have to push back against the poisonous rhetoric and policies that seek to erase us. And it’s exactly why the work of cultural institutions like the GLBT Historical Society and Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco is so important. They provide exposure to new ways of imagining, providing glimpses into worlds that many of our visitors may otherwise never be able to experience.

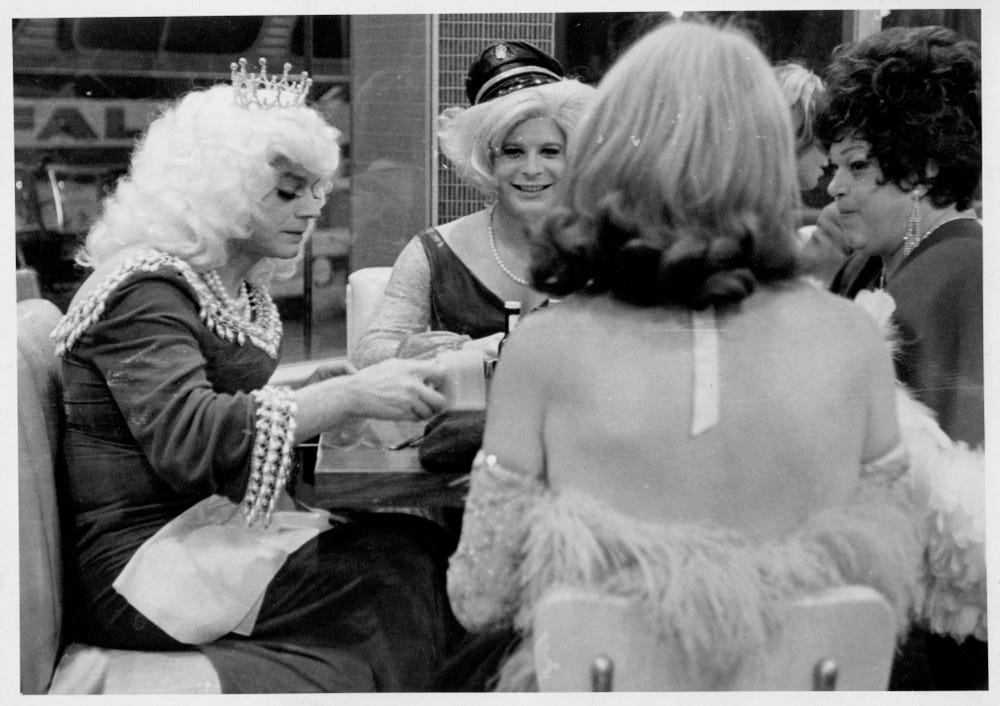

At our Castro museum — the first of its kind in the United States — we uplift more than a century of incredible LGBTQ history. We shine a light on the drag performers who entertained crowds more than half a century ago. We highlight the brave transgender folks who stood up against police brutality at Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco in 1966, one of the first uprisings of LGBTQ people in America. We share personal stories from Asian and Pacific Islander elders engaged in AIDS activism, community building, or simply creating a joyful existence. We show a century’s worth of home movies documenting queer joy, chosen families, and the places throughout San Francisco that have been home to a wide range of LGBTQ communities.

Inside Gene Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood, ca. 1966. Photo by Henri Leleu, Henri Leleu Papers (1997–13), GLBT Historical Society

Cultural institutions like ours are important because we invite audiences to explore new ways of being, and to inhabit the perspective of another person, even if only for a few moments.

In the newest exhibition at our museum, we invite visitors inside the hot-pink universe of drag performer Doris Fish. The show encourages visitors to get lost in her world, ponder the distance between her reality and ours, and imagine what it would be like to feel just as glamorous as she did.

While the subjects differ significantly, the incredible new exhibition at the de Young by Kehinde Wiley, An Archeology of Silence, similarly invites viewers to inhabit the artist’s perspective. The beautifully rendered portraits and sculptures responding to systemic violence against Black people force questions about who belongs in a fine arts space, how those killed within a violent system should be remembered, and even how much space — mental and physical — we allow those taken from us to occupy.

Installation view of Kehinde Wiley: An Archeology of Silence, de Young Museum, San Francisco, 2023. Photo by Gary Sexton

This is how cultural institutions play a role in social change. We provide the antidote to the hateful ideas being spread by extremists. We deconstruct the silences and invisibilities that have been built up around us.

Tens of thousands of people visit the GLBT Historical Society Museum each year, most of them from outside of the Bay Area. And they take the perspectives and ideas from our institution back with them. In this way, we serve as a hub for a global exchange of information, ideas, and hope for a better future.

The segment of one of the original rainbow flags created for San Francisco Gay Freedom Day 1978 rests in its case at the GLBT Historical Society Museum. Photograph by Andrew Shaffer

As we celebrate the beginning of Pride month — itself a commemoration of a fight against police brutality — I invite you to visit our museum in the Castro district and experience our vast queer past for yourself. We have countless stories to tell and some truly incredible objects, from the only known remnant of the original rainbow flag to a 1960 map of lesbian hot spots to gender-bending photos from the California gold rush.

How do you combat a violent movement determined to erase an entire community? By continuing to share the stories of the people whose shoulders we stand on. By showing that we've always been here — and aren’t going anywhere.

Text by Roberto Ordeñana, executive director of the GLBT Historical Society. Learn more about the museum, the archives, and how to get involved at glbthistory.org.