A Testimony to These Times: “The de Young Open” Art Acquisitions

By Timothy Anglin Burgard, Emma Acker, and Lauren Palmor

March 11, 2021

One of the most significant features of The de Young Open was the option for the artists to sell their works and retain all the proceeds. While the myth of the “starving artist” who lives and dies only for their work may appear romantic in a fictional film or novel, artists living in the real world deserve to be paid for their years of study and skill. In response to the extraordinary breadth, depth, and quality of the exhibited artworks, and as a gesture of support for the local artists who enrich our cultural landscape, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco purchased sixteen works from The de Young Open. Here, the three American Art Department curators describe why they find several of these acquisitions personally meaningful.

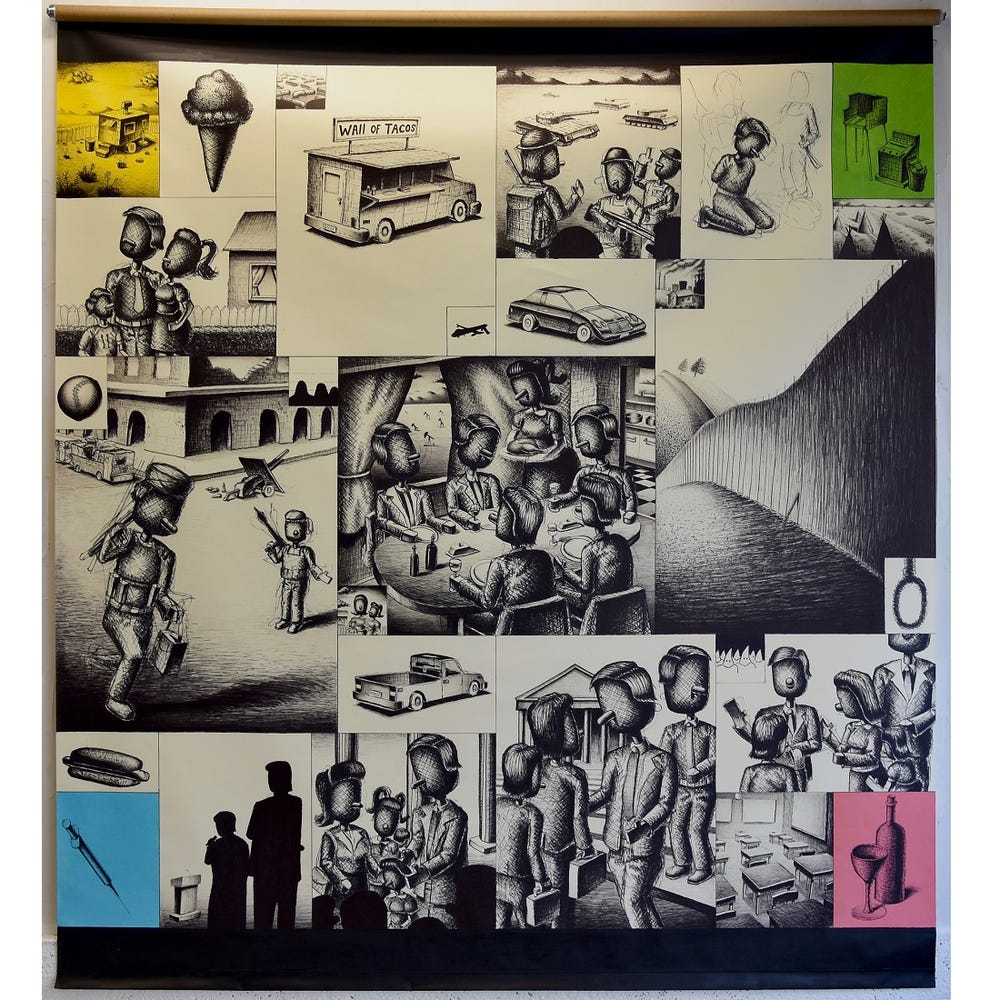

Evri Kwong’s This Land Is Your Land, This Land Is MY Land (2020)

Like many people, when I was very young I thought of art museum visits as a form of travel that enabled me to see magical and mysterious objects from other places and times. Art museums also seemed to present themselves as sanctuaries where one could seek temporary shelter from the problems of ordinary life.

However, as I grew older, so did my appreciation for the artists who remind us that art museums, while seemingly a world unto themselves, are also part of the real world outside their windows. While offering visual beauty, mental stimulation, and spiritual inspiration, art objects can also challenge and critique the stories we tell ourselves by revealing hidden truths.

Evri Kwong's painting This Land Is Your Land, This Land Is MY Land (2020) reinterprets the title of Woody Guthrie's famous 1940 folk song to pose questions regarding issues of racism, inequality, and corruption that impact people living in the United States. Although Guthrie’s song typically is interpreted today as a patriotic anthem to the beauty of the American landscape, it actually offers a critique of the contrast between the United States’ high ideals and its harsh realities.

Evri Kwong, This Land Is Your Land, This Land Is MY Land 2020. Mixed media on window shade, 80 x 72 in. (203.2 x 182.9 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, the American Art Trust Fund, 2020.42

One of Guthrie’s original song verses criticizes the wealthy who hold private property unavailable to other Americans, an issue underscored by Kwong, who intentionally capitalizes the word “MY” in his painting’s title. A second song verse describes the poverty and hunger that gripped the nation during the Great Depression of the 1930s—a situation that led Guthrie to end his song with, “I stood there wondering if / This land was made for you and me.”

Similarly, Kwong’s cartoon-like composition juxtaposes twenty-eight contrasting images that pose tough questions regarding America’s international interventions, as well as issues of inequality, global warming, drug addiction, and racism here in this country.

Evri Kwong discusses his work on our Youtube channel.

Kwong’s powerful visual comparisons include an American family enjoying a Thanksgiving dinner while flanked by scenes of war in Syria and the border wall with Mexico; a small, rural camper home adjacent to a suburban house with a white picket fence; factories belching pollution and the Dakota Access Oil Pipeline on the Standing Rock Reservation; an ice cream cone and a hot dog with prescription pills and a syringe; and Barack Obama’s inauguration as president of the United States with a crowd of Ku Klux Klan members and a hanging noose.

Like snapshots collaged in a photo album, Kwong's images depict individual episodes from the history of the United States, but he leaves it to viewers to reconcile the best and the worst aspects of our nation’s history. His use of an actual window shade that can be rolled up or rolled down by viewers pointedly introduces the idea of what issues Americans choose to see—or to block from their sight.

- Timothy Anglin Burgard, Distinguished Senior Curator, Curator-in-Charge of American Art, Curator of The de Young Open

Tom Colcord’s Gentrification of the Dead (2019)

As a native of Oakland, California, I have fond memories of taking trips with my mother to various parts of the Bay Area on BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit), sometimes riding out to “the end of the line” to visit a new locale. One such adventure was to Colma, an incorporated town of 2.2 square miles located on the San Francisco Peninsula. Although my recollections of the experience are vague, forever emblazoned in my mind are images of tightly clustered homes clinging to hilly streets, and of wide expanses of vivid green lawn. The latter comprise Colma’s predominant landscape feature: the seventeen cemeteries that have earned the town the moniker, “City of Souls.”

Inspired by Kate Laster’s 2019 San Francisco Art Institute M.A. thesis, San Francisco–based artist Tom Colcord’s surreal and hauntingly beautiful painting, Gentrification of the Dead (2019), reflects on the strange and disturbing local history that helped shape Colma—which was originally named Lawndale when it was founded as a modern-day necropolis in 1924. At the turn of the twentieth century, to make room for more housing, San Francisco passed a series of ordinances first banning burials in the city, then calling for the closure of cemeteries. Ultimately, more than 150,000 dead bodies were moved from graveyards in San Francisco to Colma, a place where the dead infamously outnumber the living. As the title shared by the thesis and the painting ironically implies, San Francisco’s deceased, like many workers here today, could no longer afford to live in the city.

Tom Colcord, Gentrification of the Dead, 2019. Oil on Canvas, 72 x 72 in. (182.9 x 182.9 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, the Volunteer Council Acquisition Fund and the American Art Trust Fund, 2020.40

Colcord layers imagery in his paintings to create, as he puts it, a “multidimensional and chaotic space” to describe “the fluidity of perception.” Gentrification of the Dead incorporates a background view of cities on the Peninsula, along with a structure that evokes a sinking mausoleum. The elegiac selection of objects in the painting is suggestive of various mourning rituals drawn from some of the diverse cultures that have shaped the San Francisco Bay Area. The Chinese paper lanterns floating ethereally in the scene reflect the influence of Chinese culture on the region. They also represent Chinese reverence for the dead—contrasting with San Francisco’s displacement of the dead in order to reinvent its landscape and real estate market. On the table at left, the headless statue of the Buddha—a figure that represents for Colcord the idea of reincarnation—symbolizes, in decapitated form, San Francisco’s neglect of the dead. The various ceramic objects and small plants in the scene recall offerings for an ancestor altar, contributing to the painting’s spiritual qualities.

Dreamlike and meditative, Colcord’s painting engages with the history and culture of the Bay Area, and offers a critical lens on the issues of gentrification and displacement that continue to affect the region. Colcord’s penetrating work resonates with that of contemporary California artists represented in our collections that similarly reveal the limitations of the California Dream.

- Emma Acker, Associate Curator of American Art

Casey Gray’s Recipe for Survival (2020)

Between the coronavirus pandemic, urgent calls for social justice, and rampant wildfires, 2020 was a challenging and transformative year, one that demanded a reexamination of our values and priorities. We have come to more clearly recognize the value of time spent with family and friends and the relative meaninglessness of material goods and pursuits. After spending a year sequestered at home, talking to loved ones over online video chats, we have come to appreciate the preciousness of our personal connections. For many, it took a year of global crises to realize how much we had taken for granted “in the before times.”

Artists have historically shown us what truly matters, and perhaps we should have been paying closer attention. For example, vanitas (or “vanity”) still lifes, which flourished in early seventeenth-century Europe, were designed to express moralizing messages about the fragility of life. These works often juxtaposed emblems of death with luxurious objects, underscoring the transience of material pleasures. After months of isolation and reflection at home, I can now more fully appreciate such representations of the passing of time and the preciousness of being.

Casey Gray, Recipe for Survival, 2020. Acrylic spray paint, molding paste, fluid acrylic on birch panel, 31 1/2 x 40 1/2 in. (80 x 102.9 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, American Art Trust Fund, 2020.41

Casey Gray’s Recipe for Survival (2020) alludes to this still life tradition, and he inventively exploits the inherent flatness of spray paint to offer a contemporary meditation on being and finding one’s purpose and spiritual sustenance in these challenging times.

Gray’s compositions begin with digital collage studies, which incorporate a variety of found source material that the artist then manipulates in order to adjust scale, palette, and composition. The final result is then sketched out by hand and spray-painted. Describing his process, Gray notes, “This tension between the digital and the handmade, and exploring the perceived overlap of the two, is reflected in multiple facets of my work. It is the conceptual foundation of my personal philosophy towards making. I believe the definition of art is the organization of experience, and my work is a testament to this idea.”

A meditation on self-reliance in the twenty-first century, Recipe for Survival expresses Gray’s belief that “hard work and a meaningful relationship to nature are essential requirements for maintaining inner peace and overcoming extreme hardship, whether that be a global pandemic or a personal misfortune.”

Watch Gray paint a pear.

The “recipe” of the work’s title calls for a large selection of “ingredients”—everyday objects chosen for their symbolic potential in relation to the relevant theme of survival in the year 2020. In addition to such essentials as firewood, a hatchet, and a skillet, Gray also includes diverse references to art, beauty, and nature—in order to survive these challenging times, we also require artistic and spiritual nourishment. In the center of the composition, a digital tablet with a cracked screen displays a traditional fruit still life, representing technology’s inability to provide a substitute for real-life experience. In the upper left corner, a gardening glove points heavenward, a monarch butterfly landing on the tip of its finger, signaling the importance of our connection to nature and the divine.

- Lauren Palmor, Assistant Curator of American Art

Learn more about how our staff organized the exhibition, and explore more of the artworks acquired from it. We are thrilled to announce our intentions of making The de Young Open a triennial event.