The Rise of Female Pastel Artists: From Rosalba Carriera to Mary Cassatt

By Furio Rinaldi

December 23, 2021

—Roberto Longhi on Rosalba Carriera, 1946She knew how to express with incomparable force the evanescent delicacy of an epoch.

Through a prominent array of works by female artists, the exhibition Color into Line: Pastels from the Renaissance to the Present sheds light on the key role women played in the development and evolution of pastel.

There are few surviving examples from the 17th century attesting to women’s experimentation with colored chalks and pastels. It was only in the 18th century that pastels became closely associated with women. This was mostly due to the overwhelming critical and commercial success achieved by a female artist from Venice, Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757), known as Rosalba, who popularized pastel as a medium for high-end portraiture. Capturing the essence of her time—sophisticated, mundane, and seductive—Rosalba’s allegories and bust-length portraits were executed through innovative techniques, such as using dry brushes and mixing pastels with water, that endowed her works with an unprecedented painterly effect and velvety finish. Her style proved to be highly influential for her male contemporaries, from Jean-Baptiste Perroneau (1715–1783) to Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789), setting pastel’s technical standards for centuries to come.

Rosalba Carriera, Portrait of a Lady as Diana, ca. 1720. Pastel On Blue Paper, Laid Down On Canvas, 13 3/16 x 10 13/16 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Prentis Cobb Hale Jr., 1959.114. Photograph by Randy Dodson, image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

While several female artists gained recognition in the previous centuries, none was more influential nor met with similar critical appreciation than Rosalba. Her achievements were recognized first by the market (as she enjoyed tremendous commercial and financial success), as well as by the critics: for her merits as a pastel artist, Rosalba was welcomed as a member by the art academies in Rome (1705), Bologna (1720) and, in a notable exception to its 1706 statute against admitting women, the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, which accepted her in Paris in 1721.

Curator Furio Rinaldi in a conversation with Xavier F. Salomon, deputy director and chief curator at the Frick Collection, on Rosalba’s impressive body of work and adventurous life.

Women’s limited access to art academies, as well as the inferior academic status initially granted to pastel and related genres (like portraiture and still life), contributed to its growing popularity among female artists in the 18th century, especially in France. When in 1770 the Académie royale finally revised its rules and resumed the admission of women, Elisabeth-Louise Vigée-LeBrun (1755–1842) was among the few artists to enter the institution and enjoy the privileges previously granted only to her male counterparts—namely, exhibiting and selling work at the state-sponsored exhibition held in the Salon Carré at the Louvre, commonly known as the ‘Salon.’

Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun, Portrait of Mrs. Spencer Perceval (née Jane Wilson, 1769–1844), 1804, Private collection. Image courtesy Wikimedia

Vigée-LeBrun mastered the crayons with superb deftness of touch, learning the craft from her father, Louis Vigée (1715–1767). “My father made very good pastel drawings; he did some which would have been worthy of the famous Latour. My father allowed me to do some heads in that style, and, in fact, let me mess with his crayons all day,” she wrote in her memoir, which she composed between 1835 and 1837. Louis Vigée’s striking portrait of his mother (Elisabeth’s grandmother) is part of the Museum’s collection and attests to his daughter’s praise.

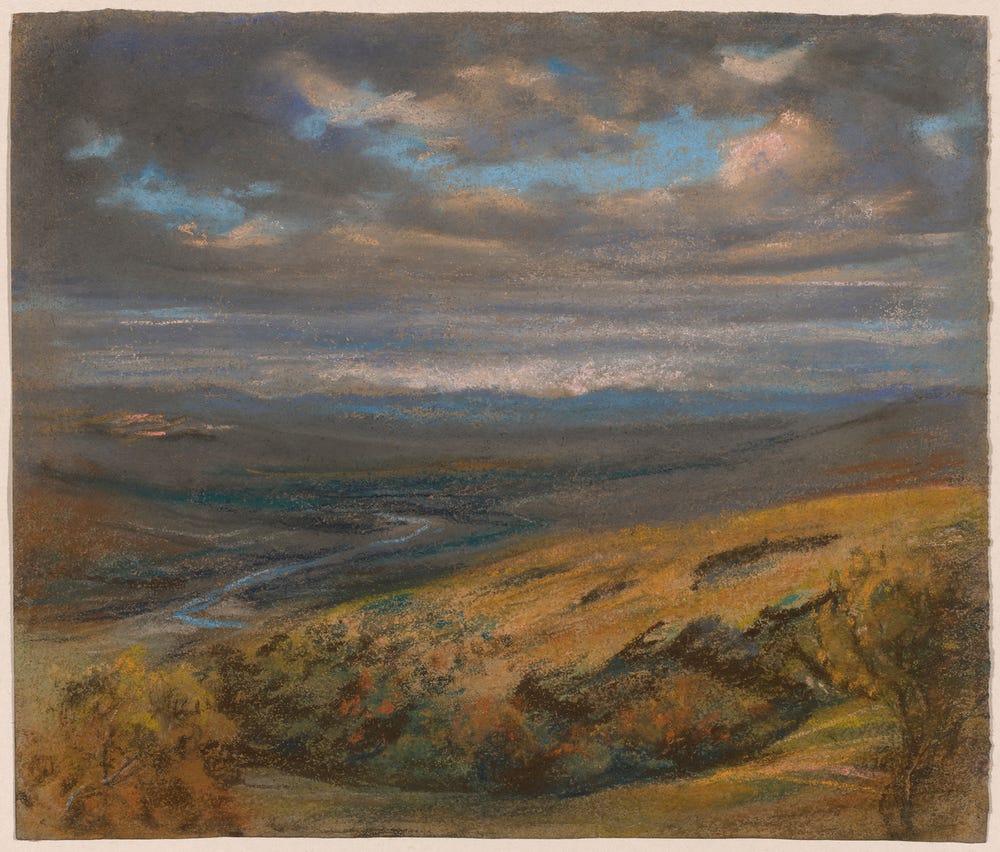

Elisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, A Hilly Landscape with a River, ca. 1820. Pastel on paper, 9 1/16 x 10 13/16 in. (23 x 27.5 cm.). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts Endowment Fund, 2021.58. Photograph by Randy Dodson, image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Mostly famed for her portraits, Vigée-LeBrun played a seminal role in the development of pastel landscapes. The artist first applied herself to the genre upon her exile to continental Europe after the French Revolution in 1789. Returning to France from Switzerland in 1808, the artist brought with her “about two hundred pastel landscapes,” by her own count, of which only approximately fifteen survive today. The rare example A Hilly Landscape with a River (ca. 1820), recently acquired by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, is characterized by its striking modernity. In taking up her pastels to immortalize the landscape, the artist inaugurated a practice that went on to flourish in the 19th century. Easy to handle and well suited for excursions, pastel gradually overtook watercolor and oils as the most popular medium for executing landscapes.

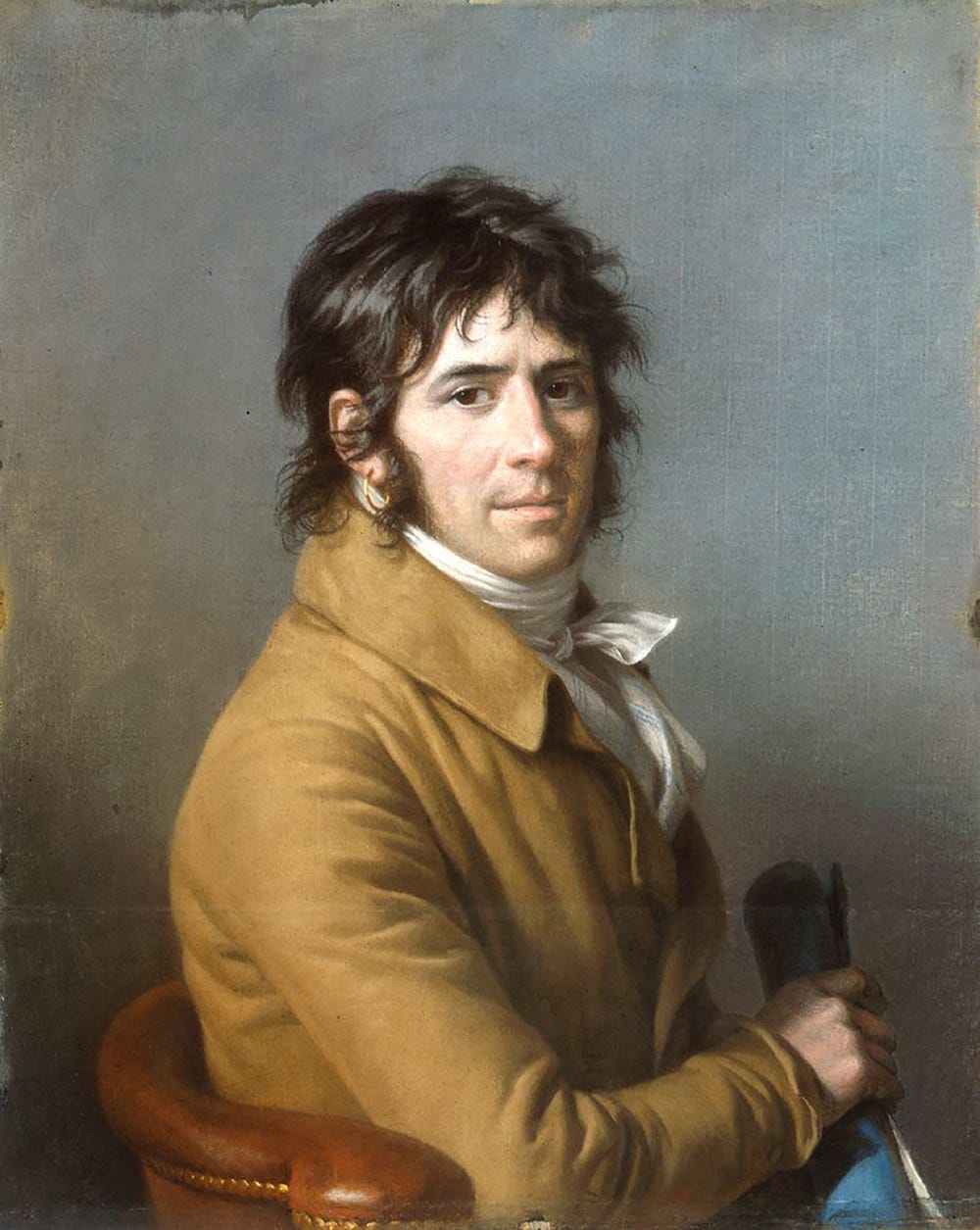

Marie Gabrielle Capet, Portrait of Marie-Joseph Chénier (1764–1811), ca. 1798. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, California, Gift of Mortimer C. Leventritt, 1941.305. Image courtesy Wikimedia

While never accepted by the Académie royale, Marie Gabrielle Capet (1761–1818) experienced an accomplished career as a pastel portrait artist. Trained and mentored by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803), another female artist working in pastel, Capet gained recognition in post-revolutionary France for sophisticated portraits characterized by cool colors and rigorous designs, as demonstrated by her portrait of the Jacobin revolutionary Marie-Joseph Chénier (ca. 1798), on loan to the Legion of Honor from the Cantor Arts Center. Fashionably decked out in a fitted redingote and cravat, his hair au naturel (without a wig), the sitter in this portrait comes to life through Capet’s spontaneous depiction of him. Her work marked an important transition from the frivolity of the ancien régime (pre-revolutionary France) to the restrained sobriety of the French Consulate period (1799–1804).

While many women in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were establishing themselves as working artists, the male-dominated market and academic circles continued to promote a gendered discourse when valuing the medium of pastel. Disparagingly, the literature from the period often compared pastels’ powdery medium, palette, and application to women’s makeup and dismissed those working in this technique as hobbyists and amateurs. To criticize the Swiss pastel painter Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789), the president of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, Joshua Reynolds, infamously stated that “his pictures are just what ladies do when they paint for amusement.” The treatment that Eva Gonzalès (1849–1883) received at the 1874 Salon exemplifies such practice, even decades later. While her ambitious realist painting Une loge aux Italiens was quickly rejected by the admission jury, her pastel La matinée rose, an intimate toilette scene, was accepted.

Curator Furio Rinaldi in conversation with Laura D. Corey, project manager and senior researcher at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, discussing challenges encountered by female artists in 19th-century France

Gonzalès’s intimate portrait of her younger sister, Jeanne, offers a luminous example of the artist’s unique and bold pastel handling: by using short hatched lines, she ensured maximum brilliance and dynamic effects. Gonzalès adopted a canvas support, whose surface provided the tooth necessary to hold the particles of color (a practice she adapted from Édouard Manet [1832–1883], her mentor). In the lower left of the work, a wide, band-like stroke is visible, where she flattened and dragged the side of the pastel stick, suggesting a wrapped bouquet of flowers.

Eva Gonzalés, The Woman in Pink (La Femme en rose) (portrait of Jeanne Gonzalès), 1879. Pastel, 45 × 37 cm. Collection of Diane B. Wilsey. Photograph courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

The birth of Impressionism marked a powerful resurgence for pastel across Europe and America. Advocating truthfulness and modernity, artists such as Gonzalès, Berthe Morisot (1841–1895), and Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) pursued a new spontaneity in pastel through highly experimental techniques and striking color effects. The medium’s saturated brilliance was particularly suited to these artists’ bold sensibilities, while its formulation, with no drying time, allowed them to execute works far more rapidly than they could with oil painting. This reduced sitters’ posing time, which was an advantage specifically in the portrayal of children, who could not (or would not) sit still for long periods. In 1898, Cassatt remarked to Harris Whittemore that pastel was, in fact, “the most satisfactory medium for [portraying] children,” a sentiment she shared with her contemporaries Morisot, Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927), and Theodore Butler (1876–1937).

Mary Cassatt, Bust of a Young Woman, ca. 1885–1890. Pastel, Over Charcoal (or Black Chalk), On Discolored Gray Wove Paper, 16 7/8 x 15 3/16 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Memorial Gift from Dr. T. Edward and Tullah Hanley, Bradford, Pennsylvania, 69.30.22. Photograph by Randy Dodson, image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Cassatt’s bold mastery of the medium is displayed in the unfinished portrait Bust of a Young Woman (ca. 1885–1890), a highlight of the museum’s collection. Drawn with dynamic and gestural strokes, the freely crosshatched backdrop of yellow and light-blue pastel lines underscores the sitter’s sour expression (made evident by her arched eyebrows). Cassatt’s bold pastel techniques and unconventional palette were deeply influenced by her close friendship with Edgar Degas (1834–1917), who held this work in his personal art collection.

Radically diverging from the painterly style of the past, female Impressionist artists preferred their pastels to have a looser, more sketch-like appearance. They often obtained this effect by using a rapid hatching system that infused works with a vibrant, lifelike quality. Gonzalès, Cassatt, and Morisot applied pastel to daring subjects with great technical prowess. In doing so, they asserted themselves as formidable artists, transcending and even overturning the traditional narrative that pastel was particularly suited to women’s assumedly “more delicate” sensibilities.

Text by Furio Rinaldi, Curator of Drawings and Prints, Achenbach Foundation for Graphics Arts at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Color into Line: Pastels from the Renaissance to the Present is on view at the Legion of Honor from October 9, 2021 through February 13, 2022.