"What a strange power there is in clothing.”

– Isaac Bashevis Singer

John Singleton Copley was largely self-taught, using the few resources that were available to him in colonial Boston. By the time he was twenty, his talent as a portraitist was widely known throughout early America. Both Copley and his patrons wanted to present themselves through portraiture—the artist, to demonstrate his technical abilities and attract new commissions; his sitters, to communicate their material wealth, status, and power.

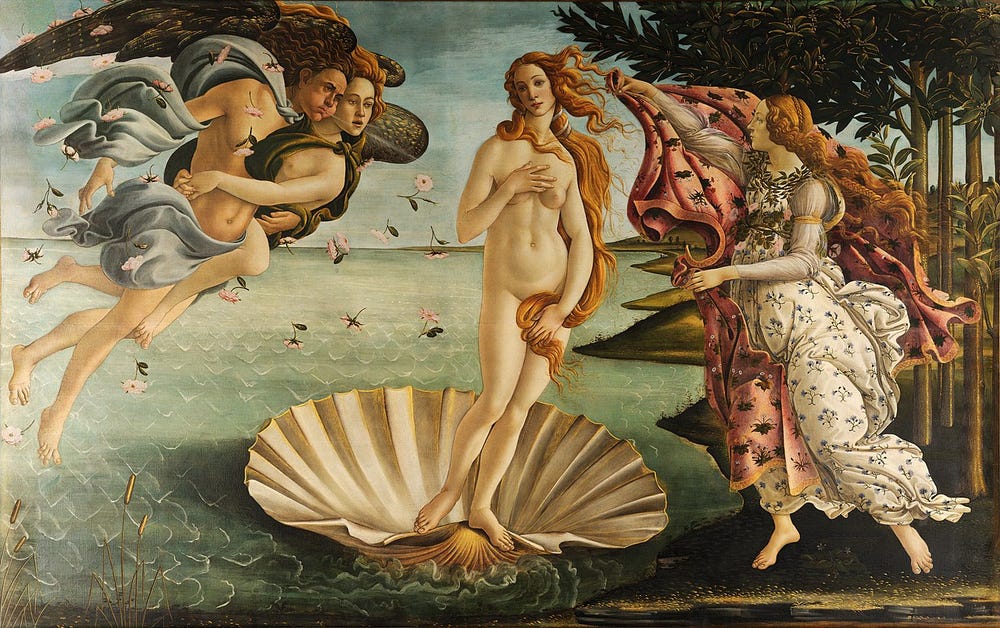

This portrait of nineteen-year-old Mary Turner Sargent was painted in the year of her marriage to Daniel Sargent, the son of a Massachusetts shipowner. Mary stands next to a fountain, a sliver of sky visible above her head. She delicately gathers the skirt of her dress, perhaps to keep it away from the splashing water, and with her right hand she holds a scallop shell—an attribute of Venus, goddess of love and beauty. The goddess Venus was symbolically born out of a shell, as famously depicted in Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, ca. 1485 (The Uffizi Collection). Although the shell constitutes a small detail in Copley’s portrait, it serves to more fully convey a sense of the sitter’s character and feminine virtue.

John Singleton Copley, Mrs. Daniel Sargent (Mary Turner), 1763. Oil on canvas, 491/2 x 391/4 in. (125.7 x 99.7 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd, 1979.7.31

Sandro Botticelli, Birth of Venus, ca. 1485. Tempera on canvas, 67 7/8 x 109 5/8 in. (172.5 x 278.5 cm). The Uffizi Collection, Inv. 1890 no. 878. Image courtesy of Wikimedia

Mary’s lavish blue satin-weave silk dress indicates her new marital status and showcases the painter’s technical mastery. Copley was widely known for his ability to paint lustrous surfaces and fabrics, and it would have been important to realistically capture this undoubtedly expensive dress made from imported silk. Copley painted at least two other portraits of women wearing this same blue dress: Mercy Otis Warren (ca. 1763) and Mary Toppan Pickman (1763). Each woman is shown in a slightly different pose, presenting various details of the gown’s luxurious fabric and trimmings, suggesting that all three portraits featuring this powerful status symbol were painted from life.

Left: John Singleton Copley, Mrs. Benjamin Pickman (Mary Toppan), 1763. Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 in. (127 x 101.6 cm). Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Bequest of Edith Malvina K. Wetmore, 1966.79.3. Image courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery; Right: John Singleton Copley, Mrs. James Warren (Mercy Otis), ca. 1763. Oil on canvas, 495/8 x 391/2 in. (126.1 x 100.3 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bequest of Winslow Warren, 31.212. Image courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston

These three portraits were among many in Copley’s oeuvre that attested to his interest in elite fashion and its ability to telegraph status and power. His 1765 portrait of Mrs. George Watson provides another compelling example of the artist’s interest in capturing the fine details of costly imported fabric, her dazzling magenta dress an affirmation of the sitter’s wealth vis-à-vis her access to European goods. Despite the strain between the colonies and Great Britain, the colonial upper class still desired imported clothing, seeking to dress in the latest English styles in order to demonstrate their good taste and access to the latest fashions from across the Atlantic.

John Singleton Copley, Mrs. George Watson, 1765. Oil on canvas, 49 7/8 x 40 in. (126.7 x 101.6 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Partial gift of Henderson Inches, Jr., in honor of his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Inches, and museum purchase made possible in part by Mr. and Mrs. R. Crosby Kemper through the Crosby Kemper Foundation; the American Art Forum; and the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 1991.189. Image courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum

Copley’s attraction to the fashions worn by the wealthy elite of colonial American was also deeply personal: though he had humble beginnings as the son of Boston tobacconists, he fashioned himself as a gentleman—intending to rise in his station, he aimed to present himself as a peer of his wealthy clientele. When John Trumbull traveled to Boston to visit Copley in 1772, he was surprised by the splendor of his clothing:

I remember [Copley’s] dress and appearance—an elegant looking man, dressed in a fine maroon cloth, with gilt buttons—this was dazzling to my unpracticed eye!

According to art historian Carrie Rebora Barrett, contemporary accounts attest to “Copley’s obsession with elite fashion and the highly differentiated goods that were a hallmark of the consumer revolution.” Copley internalized these values and created a body of work that provides evidence of some of the various ways in which the early American elite dressed to communicate their economic, social, and political power, both real and aspirational.

Text by Lauren Palmor, assistant curator of American Art. This text is an excerpt from the selected works publication, de Young 125, available for presale in Spanish, Mandarin, and English from the Museum Stores.

Learn more about American art at the de Young.