Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497–1543), Portrait of Henry VIII (detail), 1540. Oil on wood, 88.5 x 74.5 cm. Palazzo Barberini, courtesy of the Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Anti ca, Rome (MIC). Biblioteca Hertziana, Isti tuto Max Planckper la storia dell’arte/Enrico Fontolan

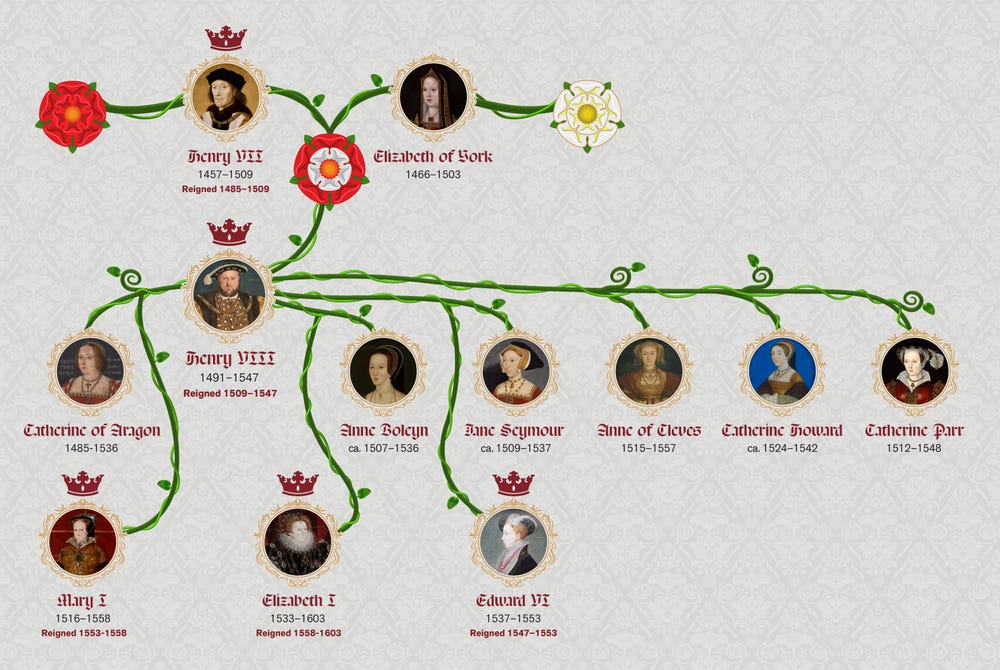

The story of the Tudors is history’s ultimate family drama, with a full cast of characters arranged in a complex family tree. Through an array of splendid artworks, The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England brings to life the court culture of this dynasty, which ruled England from 1485 to 1603. Here is a breakdown of the major figures in the exhibition and how they relate to one another and other prominent figures in 16th-century and present-day Europe.

Henry VII

Henry VII (1457–1509; r. 1485–1509) was the founder of the Tudor dynasty. Prior to his reign, the Plantagenet dynasty had ruled England since 1154. This dynasty was divided into two rival branches, the houses of Lancaster and York. The houses engaged in an intermittent civil war over the English crown, referred to by historians as the Wars of the Roses (1455–1485). Henry VII had a distant claim to the Lancastrian line through his mother, Margaret Beaufort (1443–1509). (His Welsh father, Edmund Tudor, had no claim to the throne.) Henry defeated the last York king, Richard III (1452–1485), in battle in 1485 and usurped the crown, bringing an end to the conflict. To heal the feud between the houses, he married Richard’s niece, Elizabeth of York (1466–1503), with whom he had four surviving children: Arthur (1486–1502), Margaret (1489–1541), Henry (1491–1547), and Mary (1496–1533). Henry sought to build alliances and secure his fledgling dynasty by marrying his children to foreign royalty. Arthur was briefly wed to the Spanish princess Catherine of Aragon (1485–1536) before his death in 1502, while Margaret was married to James IV of Scotland (1473–1513). Margaret’s descendants, including her granddaughter Mary, Queen of Scots (ca. 1542–1587), were distantly in line for the English throne. Through cautious politics and miserliness, Henry VII amassed a fortune and built a stable foundation for his younger son, Henry VIII.

Henry VIII

Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497–1543), Portrait of Henry VIII, 1540. Oil on wood, 88.5 x 74.5 cm. Palazzo Barberini, courtesy of the Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Anti ca, Rome (MIC). Biblioteca Hertziana, Isti tuto Max Planckper la storia dell’arte/Enrico Fontolan

More confident than his father and in possession of a full treasury, Henry VIII spent lavishly on the construction of new palaces and sumptuous works of art to adorn them. He was the classic Renaissance prince: chivalrous, highly educated, and a patron of artists and scholars. Seeking to rival the courts of his counterparts, especially Francis I of France, Henry raised the English court to a new level of sophistication. Despite his religious conservatism, he severed England’s ties with the Catholic Church in 1533. He established himself as Supreme Head of the Church of England, wielding spiritual and secular power over his subjects. His later reign was increasingly tyrannical. He dissolved monastic establishments and confiscated church property. He invaded France in 1544 and executed hundreds of his subjects for refusing to acknowledge his authority. Despite this, it was Henry VIII who brought English court culture fully in line with the standards of the Renaissance through his patronage of artists such as Pietro Torrigiano (1472–1528) and Hans Holbein the Younger (ca. 1497–1543).

The Six Wives of Henry VIII

Hans Holbein the Younger, Jane Seymour, 1536. Oil on wood, Framed: 35 1/4 x 25 13/16 x 1 3/4 in. (89.535 x 65.564 x 4.445 cm), Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Gemäldegalerie, 881

Henry VIII notoriously married six times, inspiring biographies, novels, films, and, recently, a musical. Upon ascending the throne in 1509, Henry married his brother’s widow, Catherine of Aragon, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. Catholic doctrine generally forbade a man from marrying his brother’s widow, but Catherine insisted that her marriage to Prince Arthur had not been consummated. The pope therefore granted special permission. Catherine was highly educated, charitable, and a devout Catholic. Of her multiple pregnancies, only a daughter, Mary I (1516–1558), survived, but Henry desperately needed a male heir. Catherine’s inability to provide the king with a son drove him to seek a divorce on the grounds that her previous marriage to Arthur had indeed been consummated. A six-year legal battle known as the “great matter” followed, with Catherine backed by her powerful nephew, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. It was the pope’s ultimate refusal to grant a divorce that compelled Henry to break with Rome in 1533. Catherine was stripped of her title and banished from court until her death in 1536.

Henry’s desire to divorce Catherine was also motivated by his love for one of her ladies-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn (ca. 1507–1536). Related to the noble Howard family, Anne was intelligent, elegant, and charismatic. Anne’s interest in the Protestant Reformation may have influenced Henry’s decision to break with the papacy. Their discreet wedding in 1533 was followed by a lavish coronation. Like her predecessor, Anne’s multiple pregnancies produced only one living daughter, Elizabeth I (1533–1603). Determined to rid himself of Anne, Henry had her beheaded on false charges of adultery and incest.

Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour (ca. 1509–1537), whom he married just 11 days after Anne’s execution, died giving birth to his longed-for son, Edward VI (1537–1553). Nevertheless, Jane was always depicted posthumously in Tudor family portraits as the mother of the heir. Now estranged from Catholic Europe, Henry sought to forge new Protestant alliances through marriage to the German princess Anne of Cleves (1515–1557) in 1540. Having fallen in love with a miniature portrait of Anne painted by Hans Holbein the Younger, Henry was repulsed by her appearance when she arrived in England. Learning from her predecessors, Anne agreed to a divorce and was rewarded with large estates. She lived out her days in relative peace as an honorary member of the royal family, with the rank of “king’s sister.”

Henry’s fifth marriage, to the teenaged Catherine Howard (ca. 1524–1542) when he was 49 ended in 1542 when he had her beheaded for adultery. His final wife, the widow Catherine Parr (1512–1548), promoted closer ties between the king and his three children, acting as a mother figure to them. She was the first woman to publish a book in English, Prayers or Meditations (1545), under her own name and supported Protestant reform. Henry nearly signed a warrant for her arrest on charges of heresy, but she persuaded him to forgive her. She outlived him and remarried before dying in childbirth.

Edward VI

Willem Scrots, Edward VI, King of England, ca 1550. Oil on wood, Framed: 28 15/16 x 32 11/16 x 3 9/16 in. (73.5 x 83 x 9 cm); 22 13/16 x 26 3/4 in. (58 x 68 cm). Compton Verney Art Gallery & Park, UK

Edward VI, the son of Henry VIII and his third wife, Jane Seymour, was nine years old when he inherited the throne. He had been educated by Protestant tutors and, under the direction of his Protestant advisers, the English Reformation accelerated. The traditional mass was abolished, and a Book of Common Prayer was sanctioned for use during church services. Edward did not live long enough to complete England’s religious transformation, dying of tuberculosis in 1553 at 16.

Mary I and Philip II

Edward was succeeded by his older, fanatically Catholic sister Mary I, daughter of Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. During her parents’ divorce proceedings, Mary was forbidden from seeing or corresponding with her mother, stripped of her status as princess, and made to serve as a maid in the household of her newborn half-sister, Princess Elizabeth, daughter of Anne Boleyn. Mary was reconciled with her father in the aftermath of Anne’s execution, but only after acknowledging her parents’ marriage as unlawful and herself as illegitimate. As queen, she reversed her father’s and brother’s religious reforms, reconciling England with the papacy and condemning some 287 Protestants to burn at the stake. Seeking closer ties with her maternal relations who ruled much of Catholic Europe, the queen married her younger second cousin, Philip II of Spain (1527–1598). The marriage was unpopular with the English nobility and, following a humiliating false pregnancy, Philip left England. Mary died childless in 1558.

Elizabeth I

Nicholas Hilliard (English, 1547–1619), Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603), 1576–1578. Oil on panel, 32 1/16 x 24 1/8 x 3/16 in. (81.439 x 61.278 x 0.476 cm). Family of James Rothschild, on loan to Waddesdon Manor since 2017, 27.2017 ©️ The National Trust, Waddesdon Manor. Photo: Waddesdon Image Library, Mike Fear

The daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth I was a moderate Protestant who sought to repair the religious divide her father and siblings had caused, and grant a degree of tolerance. Surrounded by Catholic enemies in Europe who regarded her reign as illegitimate, including her cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, Elizabeth established far-reaching diplomatic relations with Ottoman Turkey and Morocco. Following England’s unlikely defeat of an attempted invasion by the Spanish Armada in 1588 sent by her former brother-in-law Philip II, Elizabeth’s reign became a golden age of prosperity and cultural achievement. Her many suitors included the likes of Czar Ivan the Terrible of Russia, but she never married. Instead, she cultivated the image of a virgin queen wed to England. Her death brought an end to the Tudor dynasty, and she willed the throne to Mary, Queen of Scots’s son, James VI of Scotland (James I of England, 1566–1625).

The Tudors’ Legacy

The legacy of the Tudors lives on in contemporary Britain. When James I’s Stuart dynasty ended in 1714 with the death of childless Queen Anne, the throne passed to George I of the House of Hanover (1660–1727). Charles III, who will be crowned king on May 6, 2023, is a ninth-generation descendant of George I. George I was a great-grandson of James I, who was a great-great-grandson of Henry VII. Therefore, although Henry VII’s dynasty lasted just three generations, Tudor blood endures in the British royal family today.

Text by Thomas Wu, former assistant curator, European decorative arts and sculpture.