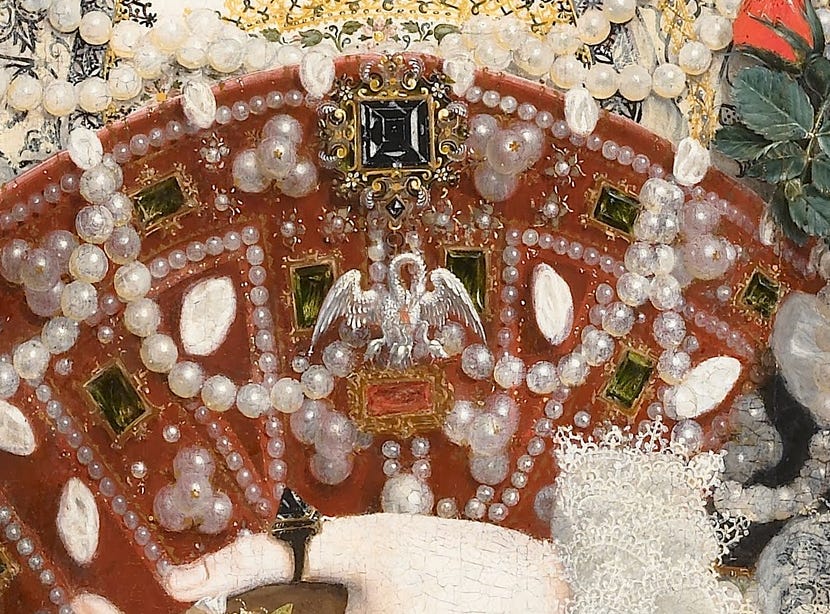

Nicholas Hilliard and workshop, Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (Pelican Portrait) (detail), ca. 1573–1575. Oil on panel, 78.7 x 61 cm. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. Presented to the Walker Art Gallery by Alderman E Peter Voues in 1945, WAG 2994. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Before Henry VIII’s two daughters, Mary I and Elizabeth I, England had never seen a woman sovereign. Its first queen, Mary I (1516–1558), ruled briefly, but left a mark through her violent efforts to return Protestant England back to the Catholic faith. Upon Mary’s death in 1558, her half-sister Elizabeth (1533–1603) inherited a realm fractured by religious wars — and wary of female rulership. Elizabeth’s early reign saw the publication of pamphlets like John Knox’s The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women (1558), which denounced female leadership as “repugnant to nature.” Ultimately, Elizabeth’s finesse as a diplomat and peacekeeper secured her right to the throne, but she faced the ongoing challenge of reconciling her gender and the authority of her rule.

Nicholas Hilliard (English, 1547–1619), Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603), 1576–1578. Oil on panel, 32 1/16 x 24 1/8 x 3/16 in. (81.439 x 61.278 x 0.476 cm). Family of James Rothschild, on loan to Waddesdon Manor since 2017, 27.2017 ©️ The National Trust, Waddesdon Manor. Photo: Waddesdon Image Library, Mike Fear

Like her Tudor forbearers, Elizabeth understood the power of portraiture to promote the legitimacy of her sovereignty, circulating her portrait widely among her subjects and at courts abroad. Nicholas Hilliard’s Queen Elizabeth I from Waddesdon Manor lends insight into how Elizabeth’s queenship found visual expression. Who can deny the majestic aura of the portrait’s sitter, flame-haired and bejeweled, with her unblemished visage and distant gaze?

Establishing a visual brand

No artist was more instrumental in the development of Elizabeth’s pictorial persona than Nicholas Hilliard (ca. 1547–1619). Though he originally trained as a goldsmith, Hilliard’s prowess as a miniaturist secured his first commission from the Queen in 1572. The fruits of this initial sitting included a charming handheld image of Elizabeth and a record of the Queen’s preferences for future depictions, specifically without “anye shadow.” Evidently meeting Elizabeth’s approval, Hilliard scaled up the miniature for a trio of rare in greate, or large-format, portraits — including the Waddesdon portrait above and the “Pelican” and “Phoenix” portraits (left and right, below). In each portrait, Elizabeth’s “shadow-free” expression betrays no worn signs of age (despite two decades on the throne), conveying the stability of her reign.

Nicholas Hilliard and workshop, Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (Pelican Portrait), ca. 1573–1575. Oil on panel, 78.7 x 61 cm. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. Presented to the Walker Art Gallery by Alderman E Peter Voues in 1945, WAG 2994. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Nicholas Hilliard, Queen Elizabeth I (Phoenix Portrait), ca. 1575. Oil on panel, 78.7 x 61 cm. National Portrait Gallery. Purchased, 1865, NPG 190. © National Portrait Gallery, London

While nearly identical in composition, the artist distinguished the Waddesdon portrait from the Phoenix and Pelican pictures with a background of crimson drapery and the ornate ensemble outfitting the Queen. Among the three portraits, no plumed fan or lace ruff is alike! In the Waddesdon portrait, Elizabeth’s dark velvet dress provides a suitable contrast for the glistening gemstones covering her person. Enameled daisies weave into her puffed, silver sleeves as pearl teardrops dangle from her powder-dusted hair, arranged to form an ethereal, winglike shape behind her shoulders. Perhaps most opulent is the gilded pelican pendant on a gold chain, flanked by Tudor roses, hanging from her shoulder.

Embodying the pelican mother

Beyond exemplifying the splendor with which the Queen surrounded herself, Elizabeth’s clothing choices were acts of self-promotion that conveyed her competence as a ruler. Wardrobe inventories indicate that Elizabeth owned at least four pelican broaches, and she frequently incorporated the jeweled motif into her portraits and dress (as shown in the Waddesdon and Pelican portraits).

Detail of Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (Pelican Portrait) showing Elizabeth I’s pelican broach

According to lore, the pelican mother plucked its own breast to feed its young in times of scarcity — even though it meant her own demise. Prominently pinned to Elizabeth’s own chest in both portraits, the pelican pendants portray this sacrificial action. Here, the bird’s nourishing blood is tastefully represented by a ruby stone. The pelican also held significance in Christian iconography. It often served as a symbol of Christ’s self-sacrifice, as he died to atone for humanity’s sins. Elizabeth’s association with the pelican not only amplified the quasi-maternal devotion she projected onto her subjects, but also reinforced her divinely bestowed position as the head of the Church of England. In these portraits, Elizabeth literally wears her role as nurturer and protector, entrusted to sustain the physical and spiritual health of her country.

Becoming an Icon

Elizabeth relied on her court to uphold and exalt her sovereignty, and the majority of her portraits were commissioned by courtiers for display at their estates. What better way to express one’s loyalty? Sir Amias Paulet, Elizabeth’s ambassador to France, led marriage negotiations between the Queen and Francis, Duke of Anjou, the younger brother of King Henri III of France. Anjou was the last suitor Elizabeth considered before adopting her “Virgin Queen” persona. Paulet ordered the Waddesdon portrait of Elizabeth from Hilliard (who also painted a miniature of Anjou) as well as a likeness of himself.

Nicholas Hilliard, Sir Amias Paulet (c. 1533–1588), 1576–1578; Rothschild Family. acc. no. 28.2017. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Elizabeth’s portrait first hung alongside Paulet’s in his Parisian residence and then, after the failure of the match, at his home in England. The pairing demonstrated — and strengthened — Paulet’s association with the sovereign. This example underscores the status Elizabeth’s image enjoyed even in her own time and how Hilliard set a new standard for royal iconography. Through the portrait, Elizabeth’s unflinching gaze continues to hold power in our own century.

Text by Isabella Holland, curatorial assistant, European paintings.