The subject of power is all around us these days as people fill our streets, some with songs and signs calling for justice and change, and others waving flags and carrying guns and pushing against that tide. People power, political power, and the omnipresent power of the relentless COVID-19 virus seem to encapsulate what power is in this moment. But when we consider what moves people or things, what effects temporary or lasting change, we find a force that is fed by a will of spirit that can be found in the very disparate yet interlocking art pieces at the de Young museum.

The de Young collection is awash with examples of power, from portraits to scenic views, but one that I find reflective of history and today is Eastman Johnson’s The Pension Claim Agent (1867).

Eastman Johnson, The Pension Claim Agent, 1867. Oil on canvas, 25 1/4 x 37 3/8 in. (64.1 x 94.9 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Mildred Anna Williams Collection, 1943.6

Certainly, an ongoing discussion in many households is how does and how should the government serve the people. Who decides who will get support and who will find a hardback or locked door? In The Pension Claim Agent we see a bureaucrat, with an open valise crowded with well-ordered papers, interviewing a Civil War veteran who has lost a leg in battle. The agent sits as the man leans on a hewn wooden crutch. The small cabin holds three generations, and one multipaned window provides the only light in the cabin, shining brightly on the agent’s face and on the observant daughter but leaving the grandparents and wife shadowed. Why, one wonders, does the man with one leg stand while the other sits? Perhaps the agent fills the last chair, but what of the bed? And why does the disabled man have to convince the agent that he is due a Civil War pension? Does the agent not see the gun the father can no longer use to hunt food for his family? Can’t he see that the man has only one leg? Doesn’t he know this man is indeed a veteran? Here, the power is clear. The agent has the power, the family the need, and the soldier is forced to plead his case and accept whatever ruling is given. It seems like this is the power of one, but it is more: There is the power of the government pulling in one way, and the power of thousands of soldiers demanding their earned pensions for duties performed and losses incurred. The end of the story is not told in this painting, but we can certainly feel the roles of the powerful brandishing the law and those powerful in spirit.

In The Pension Claim Agent the petitioner and adjudicator are mortals, with human strengths and fragilities. The Nail and Blade Oath-taking figure (19th century) from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, like the pension claim agent, wields power and authority and helps to deliver assessments and justice. But its power lies in the human petitioner reaching into the world of the ancestors for guidance and deliberation.

Nail and Blade Oath-taking figure, 19th century. Wood, metal, nail, horn, branches, and glass, 32 1/2 x 12 in. (82.6 x 30.5 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, gift of Mrs. Paul L. Wattis and the Fine Arts Museums Acquisition Fund, 1986.16.1

When I first started to teach poetry at the de Young, this figure stood in a gallery in the old de Young building, which was being refilled with art objects after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. I was drawn to the object, which even in the mostly empty gallery radiated an energy. Once coated in sacred oils, this carved image was meant to serve as a nexus for resolving disputes and making judgments. Vows and promises were embedded into the effigy with a blade or nail. Maybe the issue was a verbal dispute, a question over property claims, a spiritual malaise that needed a balm, or even a resolution to a murder. A naganga, or specialist in the realm of spirits, guided the discussion or argument through ritual, chants, and insights. Each detail of the carving has significance. A bilongo, or small cloth bundle, would contain seeds and medicinal elements that fed the spirits. The bell is a call to the spirits. The mirror at the figure’s center is an entrance to a spiritual realm. Here the powerful authority is not the human world of government officials and the common man, but the power of the ancestors, the power of the dead to bring justice and mete out protection or punishment as needed. It is not the government official, or even the spiritual guide, who judges but the divine spirits awakened by a naganga who invokes their power.

Unknown artist, La Carreta de la Muerte (“Chariot of Death Carrying the Angel of Death”), ca. 1900. Cottonwood, horsehair, glass marbles, paint, leather, string, nails, paper, and fabric, 40 x 48.5 x 20 in. (101.6 x 121.9 x 50.8 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of the Haley Family Trust, 1995.28a-e

Both the The Pension Claim Agent and the Nail and Blade Oath-taking figure show demonstrations of power on the lives of specific individuals seeking a hearing or needing counsel. But the idea of power operates on a far more profound level in La Carreta de la Muerte (Chariot of Death Carrying the Angel of Death; ca. 1900), which affects every person. While the first two art objects require an appeal, this third power object exists as a reminder that we are all powerless under its control. Death is always present in our lives—perhaps it touches a relative, perhaps a celebrity some admire or try to emulate, or perhaps it surfaces as a body count—those slain in extrajudicial killings, those struck down by COVID-19, those struck down by accidents and illnesses, those struck down in war. Death riding its chariot comes close to our homes and the angel enters without our bidding and will not leave despite our prayers and pleadings. Here is power in its most simple form. It is a power that can sometimes be forestalled but never vanquished.

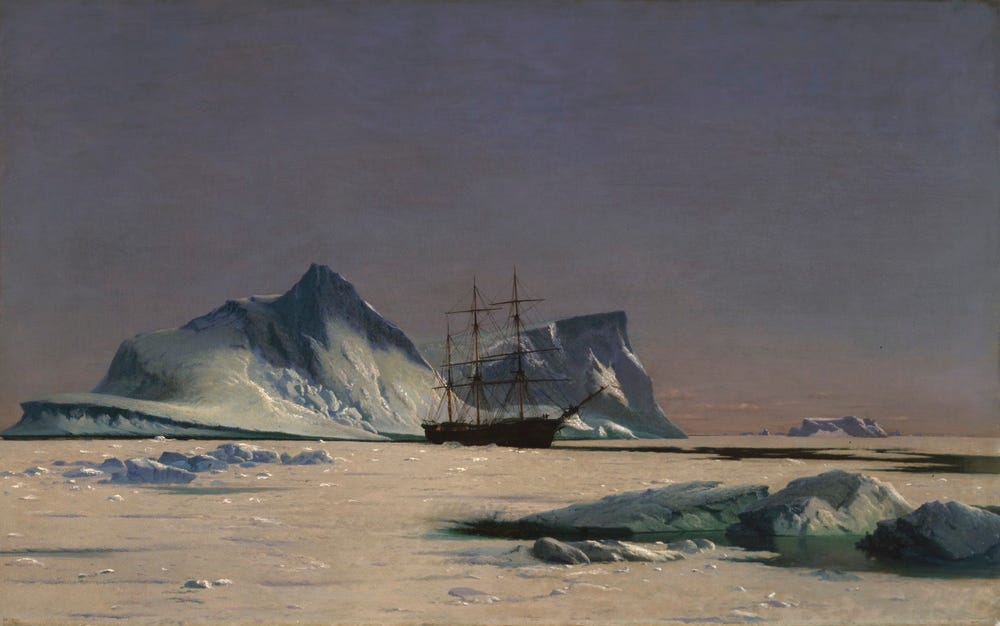

William Bradford, Scene in the Arctic, ca. 1880. Oil on canvas, 29 5/8 x 47 5/8 in. (75.2 x 121 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Agnes van Eck Reed, 1991.39

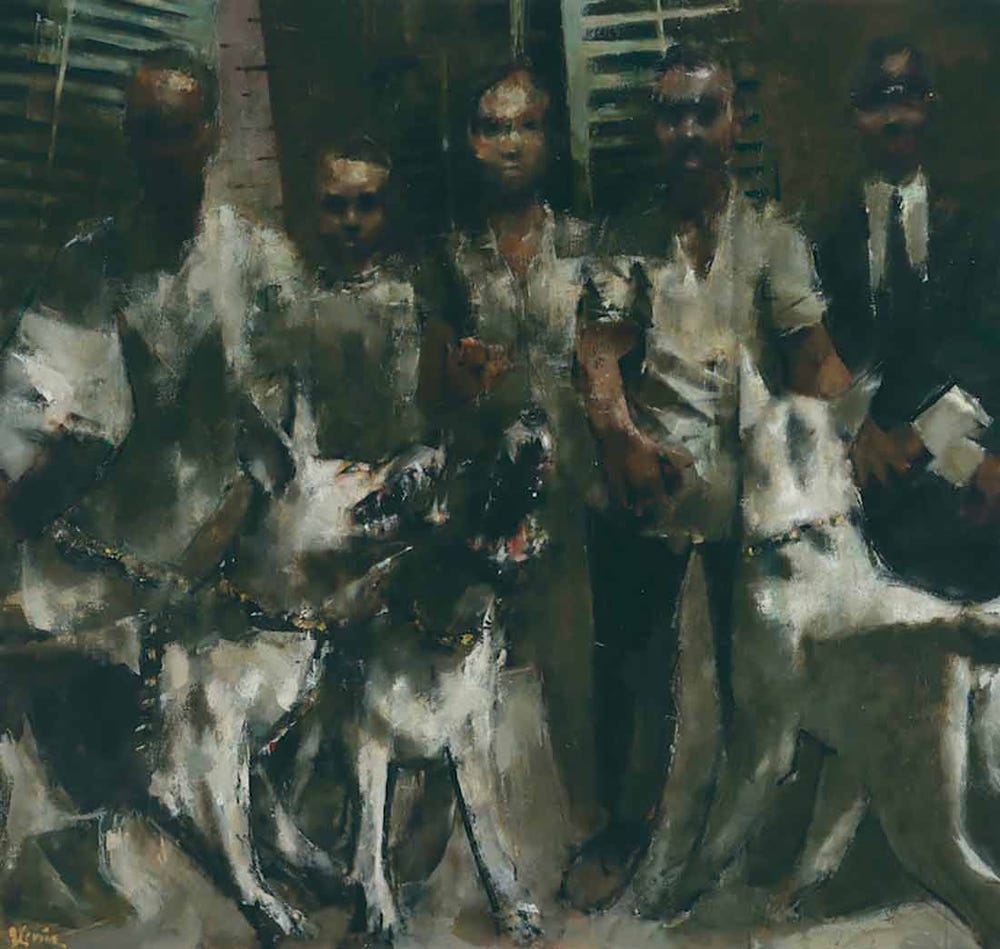

Power has many manifestations in the de Young. The icy arctic trapping a ship until the spring heat melts the frozen bay in William Bradford’s Scene in the Arctic (ca. 1880), the shields and spirit boards of New Guinea, or the resisting young people in Jack Levine’s Birmingham ’63. There is The Gold Scab: Eruption in Frilthy Lucre (The Creditor) (1879), by James Abbott McNeill Whistler, which shows the ability of the artist to ultimately trump the power of money, in this case by depicting his creditor as a monster, and there is also power that is gentle, comforting, and unifying as in Frederic Edwin Church's Rainy Season in the Tropics (1866). In this museum there is art that reflects power that is physical, transactional, environmental, spiritual, and artistic. We can see that while humans do have certain powers, ultimately we are only one part of our complex universe and some powers extend beyond our grasp and outside our vision, even as we join together to manifest our power and make threatening and destructive, or nurturing and sustaining, change.

devorah major is a poet, novelist, essayist, and former FAMSF poet-in-residence. She is San Francisco's third Poet Laureate.

Jack Levine, Birmingham ’63,1963. Oil on canvas, 71 x 75 in. (180.3 x 190.5 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Dr. Leland A. Barber and Gladys K. Barber Fund, American Art Trust Fund and Mildred Anna Williams Collection, by exchange, 1999.69. Art © Susanna Levine Fisher/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, The Gold Scab: Eruption in Frilthy Lucre (The Creditor), 1879. Oil on canvas, 73 1/2 x 55 in. (186.7 x 139.7 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mrs. Alma de Bretteville Spreckels through the Patrons of Art and Music, 1977.11

Frederic Edwin Church, Rainy Season in the Tropics, 1866. Oil on canvas, 56 1/4 x 84 1/4 in. (142.9 x 214 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Mildred Anna Williams Collection, 1970.9