Power on Paper: Kara Walker’s Resurrection Story with Patrons

By Sarah Mackay

February 16, 2023

Installation view of Paperworks: 15 Years of Acquisitions

It is human to desire power. It is our agency (our capacity to exert power) that enables us to control our own destinies and be active participants in our own lives. When this piece of our humanity is threatened, we feel compelled to act — protesting, voting, or seeking comfort in family and friends. As writer devorah major recalls in her Prisms of Power, over the past few years, we have all in some way felt our power threatened. From 2020 through 2022, the global population was forced into isolation due to a virus that caused widespread death and devastation (as well as exasperation) outside of our control. Just months ago, people rallied in the streets to protest the overturning of Roe v. Wade — the landmark 1973 US Supreme Court decision that established the constitutional right to an abortion — quite literally the right to choose what happens to your own body.

Throughout history, like our city streets, art has served as an effective space for exposing power imbalances and confronting their consequences. Paperworks: 15 Years of Acquisitions is the inaugural exhibition in the Legion of Honor’s new works on paper gallery. It explores the visual history of power (among other universal themes) through a selection of acquisition highlights from the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts. The works in the Dynamics of Power section span seven centuries and examine how power imbalances were embedded in art making throughout early modern Europe, as well as how they are addressed in contemporary art today. Of the works on view, none confronts the repercussions of entrenched systems of power with more fervor and clarity than Kara Walker’s Resurrection Story with Patrons (2017).

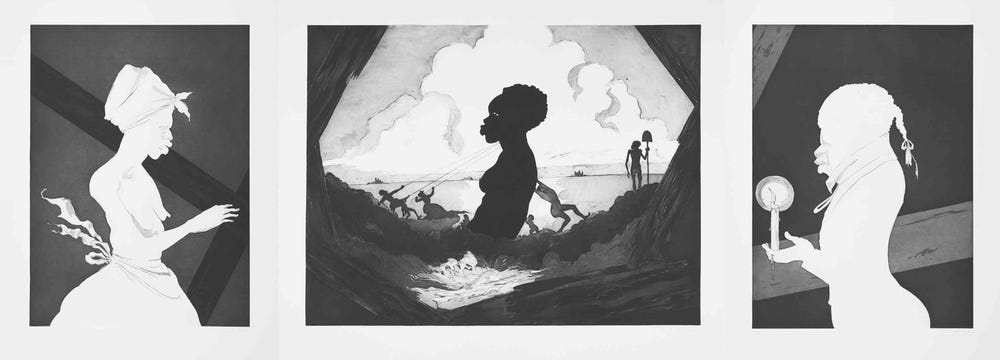

Kara Walker, Resurrection Story with Patrons, 2017. Etching, aquatint, sugar-lift aquatint, spit-bite aquatint, and drypoint, 39 3/4 x 30 in. (101 x 76.2 cm) (each sheet). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts Endowment Fund, 2017.28.1-3

In the spring of 2016, Walker visited Rome as the American Academy in Rome’s Roy Lichtenstein Artist in Residence. She spent her days exploring and studying the numerous Renaissance and Baroque churches, museums, and monuments that continue to define Rome’s secular and religious history, and its cityscape. An influential period of her artistic development, this led her to consider how myth, martyrdom, and the iconography of Christianity intersect with the legacy of slavery in America. Met with the burgeoning Black Lives Matter movement upon her return to the United States, she began an extensive investigation of these questions, resulting in the exhibition The Ecstasy of St. Kara: Kara Walker, New Work at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Kara Walker, Monomentality, 2016. India ink on paper, 35.75 x 47.5 in. (90.8 x 120.7 cm). Artwork © Kara Walker. Image courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co. and Sprüth Magers

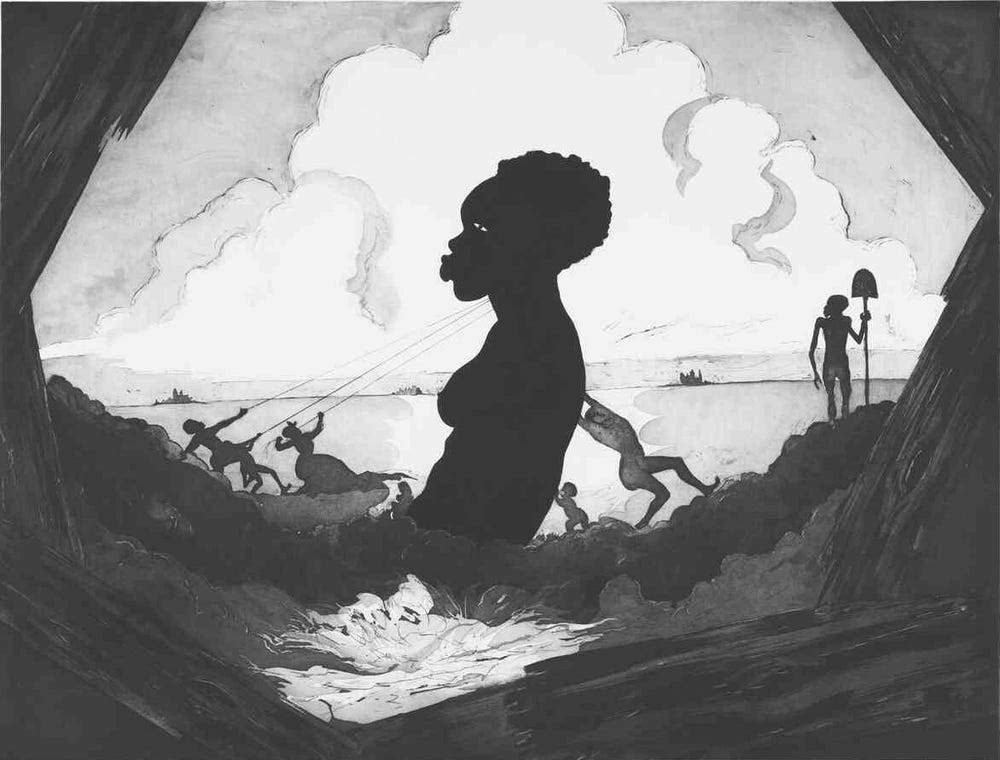

A departure from the provocative cut-paper silhouettes for which Walker is known, the works in the exhibition were exclusively drawings. One of these, entitled Monomentality (2016), depicts a statue of a Black woman being hoisted from the ground by a rope tied around her neck, pulled by small-scale figures, an explicit reference to lynching and the tools of enslavement. In Resurrection Story with Patrons, Walker replicates this image, expanding the composition by adding two prints alongside it. This format, called a triptych, references altarpieces Walker would have seen in numerous Christian churches during her Roman sojourn. Each of the flanking prints features a white silhouette of an African American figure, one male and one female, dressed in antebellum-style clothing. They are turned to face center with their hands raised at chest level. As the work’s title suggests, they are posed just as patrons would have been in a Renaissance-era altarpiece.

Kara Walker, Resurrection Story with Patrons, detail

Kara Walker, Resurrection Story with Patrons, detail

Artistic production in Renaissance Europe was as much a public negotiation of power as it was a creative endeavor. Fueled by patronage — the act of commissioning a work of art — wealthy private individuals, clerics, and members of the state would give an artist numerous specifications for a project. Often these instructions included incorporating explicit symbols to convey flattering messages about the patron. Artists worked largely at the patron’s will.

Walker’s triptych emerges from the tradition of including the patron’s portrait within a commissioned work as a means of conveying their religious sanctity, wealth, or aesthetic taste. The format of her composition, with the patrons at the two sides, replicates many well-known altarpieces, such as the celebrated Portinari Triptych (c. 1475). Painted by Flemish artist Hugo van der Goes and commissioned by Italian banker Tommasso di Folco Portinari, the work was created for the hospital church of Santa Maria Nuova in his native Florence. In the painting, Portinari and his two sons, Antonio and Pigello, are depicted in the left panel, while portraits of his wife Maria and daughter Margherita are rendered on the right. Similar to those in Walker’s triptych, all the figures raise their hands in prayer. When it was unveiled in 1483, the Portinari Triptych was met with great awe and enthusiasm by the Florentine public. By including himself in the painting, Portinari showcased his taste and wealth, and broadcast his family’s piety and closeness to Christ, a power play by the patron that depended on the skill of the artist.

Hugo van der Goes, The Portinari Triptych (or Adoration of the Shepherds with angels and Saint Thomas, Saint Anthony, Saint Margaret, Mary Magdalen and the Portinari family), c. 1475. Oil on panel, 107 ⅞ x 256 ⅝ in. (274 x 652 cm), Uffizi, Florence

Walker acknowledges the inherent power imbalance in the artist-patron relationship: the glorification of artworks and the people depicted within them over their makers and those who may be left out of these narratives entirely. Identifying parallels between these dynamics and the enduring legacy of slavery, Walker questions what truths lie untold behind paintings, monuments, memorials, and other built structures. In Resurrection Story with Patrons, she unveils these hidden stories. The female at left supports a cross, a symbol of martyrdom and bodily suffering. The male at right stands in front of a wooden beam, which may reference the wooden ships used to traverse the Middle Passage. Both figures are dressed plainly, the woman without a shirt. These “patrons” do not boast their wealth, reputation, or sanctity; instead they are martyrs.

For Walker, the presidency of Barack Obama, whom she refers to as the “President of Hope” in her 2016 essay “Assassinations by Proxy,” unleashed “ancient racist anxieties” that spurred the killings of multiple Black men and women as proxies for the President. While the two patrons in her work represent the many Black Americans who were killed throughout the Civil War period, they also call to mind these proxies, including Michael Brown and Tamir Rice, named in her essay, among many others.

Kara Walker, “Assassination by Proxy,” 2016Saviors don’t arrive without martyrdom at their heels.

In returning to these historic objects and formats, Walker reveals how our monuments, such as Confederate statues, shape the lived experiences of Black Americans. She makes clear the power imbalances inherent in our built environments. Nevertheless, as the wood beams on the patrons’ shoulders guide our eyes to the central scene, Walker provides an ambiguous but ultimately uplifting message of hope. Raised from the earth, the Black sculpture emerges from the ground like a surrogate for the many antiquities unearthed in Rome during the 15th and 16th centuries. As the work’s title claims, the sculpture is literally resurrected. The figure’s eyes are open, as if she’s been brought to life, much like Christ after his crucifixion. With her head surrounded by billowing clouds, she is a beacon, a promise to the onlooking patrons and Black Americans of a new means of commemorating their stories. Here, Walker offers a model for how monuments and memorials can be reimagined to contend with historic and ongoing racial injustice. Wielding her power as storyteller and image maker, Walker reactivates history to advocate for a better future, giving life to her belief “in the power of people to creatively work our way to being a better community of souls.”

Text by Sarah Mackay, assistant curator of prints, drawings, and photographs.

Works cited

Walker, Kara, “Assassination by Proxy,” in The Ecstasy of St. Kara (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).