When I was a kid, Juneteenth was always a magically timed celebration. School was just letting out, the frigid Minnesotan air would hastily change to thick heat that stuck to your skin, and the church barbecue would last well into dusk—music playing, folks laughing. There was a sense of grounding for me in understanding that the roots of my being were not confined to the traditional nuclear family but also included the in-between relationships. The unspoken kinship felt when Black people commune and love, together. It would often take us over an hour to get our plates, and our goodbyes, together to leave.

This Juneteenth, the air is also thick here in Northern California, but not necessarily due to heat. This year some people are hugging friends, lovers, and family for the first time in over a year. Another traumatic fire season is quickly approaching. Online we’ve witnessed a full cycle of black squares, to yellow ones, to Palestinian flags, to rainbow gradients. And I cannot help succumbing to a feeling of whiplash, with a touch of déjà vu.

Juneteenth comes at a time where we, as a country and a species, are being asked (once again) to grapple with the vestiges of not only the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade but also the deep and long-lasting harm white settler colonialism produces globally. As I hope all of us know, the slave trade created the blueprint for all forms of structural, societal, and political racist subjugation.

Hell, people even created entirely new forms of art to help justify the kidnapping, torture, and subsequent enslavement of millions of humans.* New legislative sectors would be made, and new industries would be built, on the backs of people who were astrologers, wise women, revolutionaries, farmers, sailors, poets, healers, and artists.

What does it mean to celebrate “freedom” when so much has been stolen in the process? What does it mean, as a Black artist, to make with this history both within and behind us?

Hice Dat Sash / “Open the Blinds” is a photographic and performative series where my mother and I traveled to monumental points in South Carolina where our enslaved ancestors worked the land. Left: “In his house, looking towards ours,” Aiken mansion in Charleston, SC. Center: “At our first stop, we throw Carolina Gold (with the hands that made it in mind),” Gadsden’s Wharf, SC. Right: “Anchoring us, this endless horizon. How many are missing?” Edisto Beach, SC. Hice Dat Sash by Yétúndé Olagbaju & Jacqueline Copeland.

Much of my artistic praxis is based in the belief that time is not linear and neither is the need to heal from the colonial brute that is America. As I continue to discover the art of my predecessors, elders, and contemporaries I can see that this belief is shared by many and likely a result of looking to other Black artists to make sense of our place in this world. To work through, within, and oftentimes, beyond the harm inflicted on Black people by this country with an artistic lens is certainly not new. And neither is our propensity as artists to provide solutions to heal it.

*Please see/read: Exposing Slavery: Photography, Human Bondage, and the Birth of Modern Visual Politics in America by Dr. Earnestine Jenkins.

Whether you are a Black thirty-year-old doctor, a sixty-something-year-old clergyman, a young healer, an eighty-year-old artist, or a retired mathematician, your generation seems to have had a historical movement towards Black liberation. And regardless of who was lost in the crossfire of progress, we often are seen (and self-identify) as a resilient people. And while I cannot deny this truth of resilience, I often wish we did not have to be so. That we (especially Black trans folks and women) could completely come undone. That we could crumple under the weight of our obligations and longings without fear of disposability. With the utmost assurance that the world would receive our complexities and hold a space there for us: to play, to be joyful, to sift through our grief.

I find this place through blood and chosen family, in loving accountability processes. I also find this place in the making and experience of Black art. I find this place when witnessing the brilliant patterning and colors in Annie Mae Young’s piece Strips, ca. 1975.

She had said that “I just put some pieces together in my own head, in my own mind how I want it.” How Miss Annie wanted it. Even forty-six years later she is teaching me about Black agency.

I find this place through collaboration with my own family and witnessing how other Black artists seek comfort, resolve, and temporal refuge in their own family trees. Through artists like Lonnie Holley, I am reminded that I cannot forget whose bravery I am “using again.”

Lonnie’s assemblage piece which “recalls both ‘family tree’ genealogies and preservation of heritage through the generations.” The piece “clearly references elders remembering their roots, but it also subtly suggests that a younger generation runs the risk of forgetting — or ignoring — the past.” Lonnie Holley, Him and Her Hold the Root, 1994. Rocking Chairs, pillow, root, 45 1/2 x 73 x 30 1/2 in. (115.6 x 185.4 x 77.5 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, American Art Trust Fund, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection. © 2020 Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

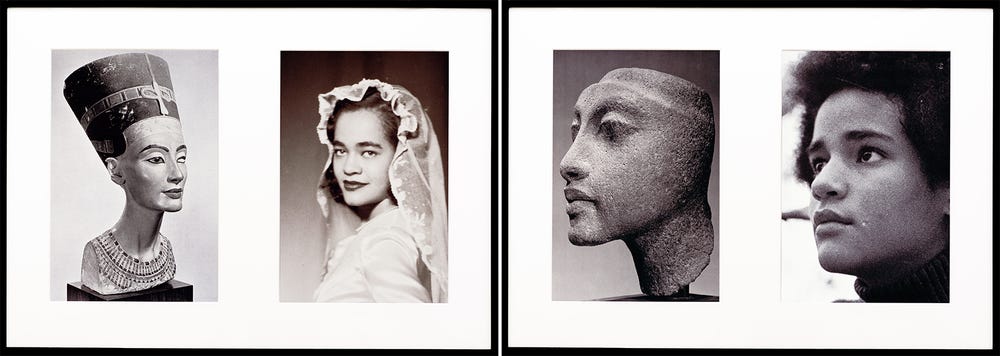

Artists like Lorraine O’Grady, through works like the series Miscegenated Family Album (1980–1994), remind me that biological familial ties can be both deeply flawed and incredibly powerful. While actual bloodlines are sacred, so are the families we build out of necessity and grief.

Left: Lorraine O’Grady, Miscegenated Family Album (Sisters I), L: Nefernefruaten Nefertiti; R: Devonia Evangeline O’Grady, 1980/1994. Cibachrome prints, 20 x 16 in. each (50.8 x 40.6 cm each); 27 1/2 x 38 x 1 5/8 in. framed (69.8 x 96.5 x 4.1 cm framed). Edition of 8 +1 AP. Right: Lorraine O’Grady, Miscegenated Family Album (Sisters III), L: Nefertiti’s daughter, Maketaten; R: Devonia’s daughter, Kimberley, 1980/1994. Cibachrome prints, 20 x 16 in. each (50.8 x 40.6 cm each); 27 1/2 x 38 x 1 5/8 in. framed (69.8 x 96.5 x 4.1 cm framed). Edition of 8 +1 AP. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York. © 2021 Lorraine O’Grady /Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

But above all else, I find this place when sorting through Black history, art, and culture in order to access something that the world often attempts to steal from us: Black futurity.

The idea of a Black future filled with comfort, and that is undoubtedly liberating.

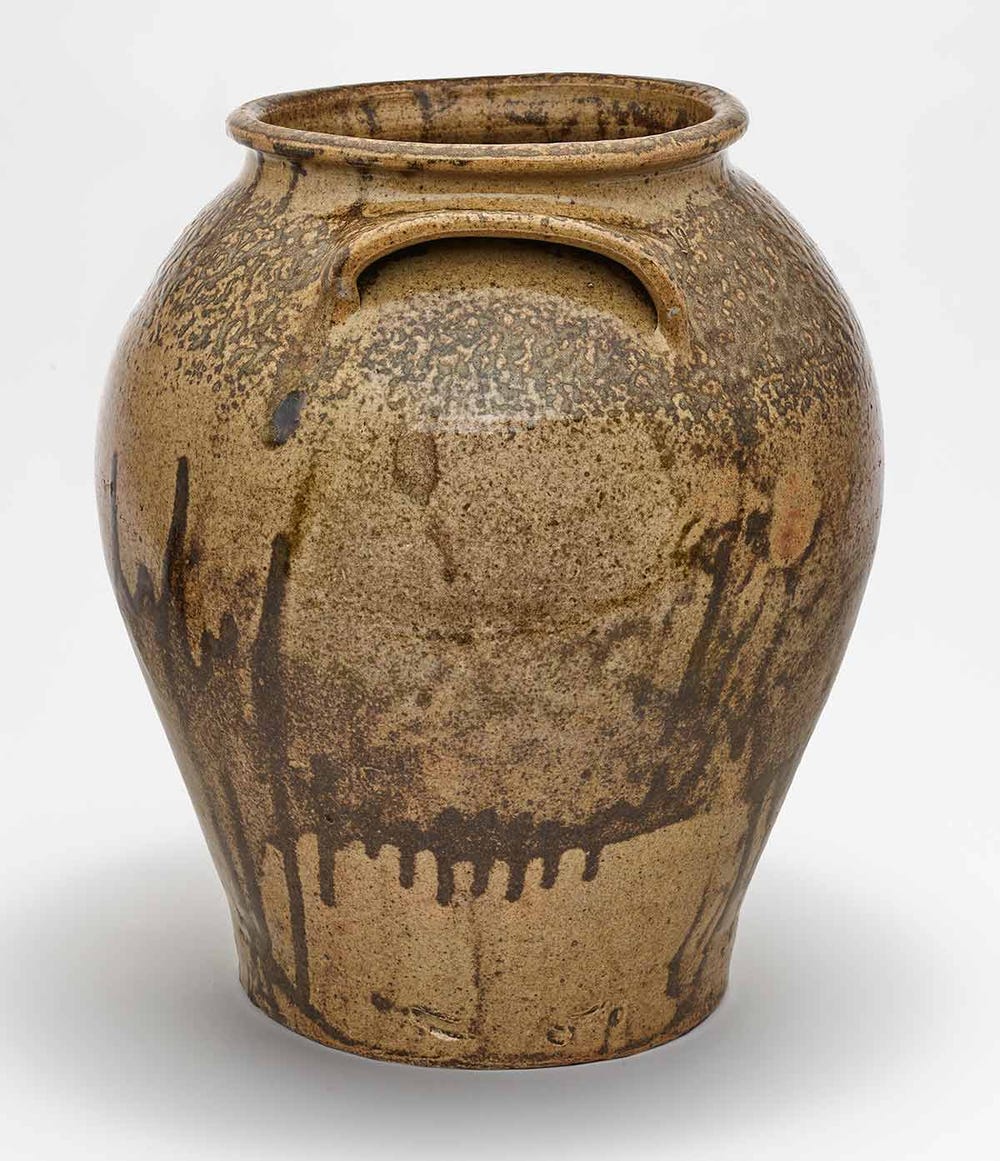

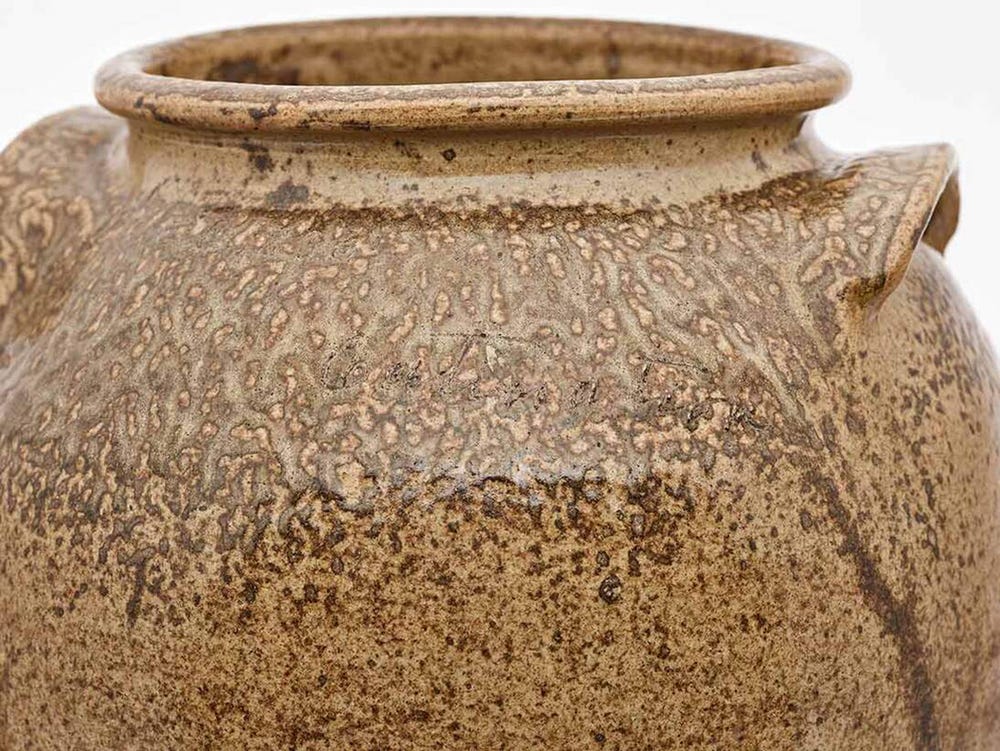

I see Black artists engaging in future-forward thinking in even the simplest form of declaration. Edgefield, South Carolina, is a three-hour drive from the plantation where my ancestors worked on Jehossee Island. There, many years before my grandmother moved from South Carolina to Philadelphia, David Drake was making clay coils for his vessels. A prolific Black potter (who was also enslaved), Drake is known for inscribing his works with sweet and playful poetry, along with his name. From what I gather, the poems range from warnings to follow the Bible to instructions on what the vessel would be best used for. As we know, this is all during a time when enslaved peoples and their descendants were not allowed to read, let alone write.

Selection of David Drake inscriptions:

Give me silver or; either gold

though they are dangerous; to our soul

27 July 1840

Made at Stoney Bluff for making lard enuff

13 May 1859

The forth of July is surely come

to blow the fife = and beat the drum

4 July 1859

I – made this Jar all of cross

If you don’t repent, you will be lost

3 May 1862

Detail: David Drake (ca. 1800–ca. 1870s) artist; Pottersville Stoneware Manufactory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, manufacturer, “Catination” Storage Jar, April 12, 1836. Glazed stoneware, height: 14 7/8 in. (37.8 cm); diameter: 12 5/8 in. (32.1 cm). Museum purchase, Calvin L. Malone American Arts and Crafts Fund, American Art Trust Fund, and American Decorative Arts Endowment Income Fund, 2020.5

Drake’s declarations of his existence, the playfulness of his prose, the self-awareness and conviction with which he writes, is full of both tenderness and defiance. With every push of his tools, every curve in his capital “D,” and every marking of the date, Drake reminds me that Black people intrinsically look to the future with hopeful and knowing eyes. That despite how hard white supremacy and violence may try, Black people can often find joy and hope in grim circumstances. That our individual proclamations of existence are often love letters to many futures.

I would be remiss to not mention that Drake’s pottery has sold for upwards of $350,000 dollars, as recently as last year. There have been no offers of reparations to his direct descendants, who are alive today. (This fact is all bitter, no sweet.)

There are so many Black artists whose works, just like the celebration of Juneteenth, are love letters to both the future and the past. They are not always the kind of love letters that are laced with perfumes or flowers. They are sometimes ones with ragged edges, missing names, and no return addresses. These letters have drops of blood, were written in dimly lit corners, and in a hushed secret.

And sometimes the letters have been lost to us entirely, and now we are tasked to write the ones we needed: the kind of love letters that wipe your tears, that remind you that you have your grandfather’s nose, that your green thumb is hereditary. The kind of love letters that remind us that refusals can (and have and will) forever alter our DNA.

These love letters are the kind that ground you. They arm you for another fight. With the explicit belief that there will be a time when your resilience is no longer compulsory.

While I will not be going to church this Juneteenth week, I will be setting an altar. One with honey, heirlooms from my great-grandmother, and artwork from my friends. I will call my mom and we will talk about our little home together in Philly, where we grew tomatoes. I will light candles and wash my dishes to Leontyne Price and Beverly Glenn-Copeland. I will tap in with friends to see where the barbecue is at.

I will dance. Allowing my feet to pound the ground beneath it in rage, grief, and delight.

I will imagine my feet are rooting with every step. Connecting to the land my ancestors worked in South Carolina. Remembering that those roots supported David Drake as he fired his July 4th vessel, that those roots find my great-great-grandfather tending to his own tomatoes as a boy.

I will breathe ocean air, I will eat stone fruits, I will draw in the sunlight.

And I will relish in my freedom to do so.

Essay by Yétúndé Olagbaju

Yétúndé Olagbaju is an artist and maker currently residing in Oakland, California. They utilize video, sculpture, action, gesture, and performance as through-lines for inquiries regarding Black labor, legacy, and processes of healing. They are rooted in the need to understand history, the people that made it, the myths surrounding them, and how their own body is implicated in history’s timeline.

Learn more about Olagbaju at yetundeolagbaju.com.