Writing American History: The Poetic Jars of David Drake

By Timothy Anglin Burgard

February 26, 2021

The Fine Arts Museums have acquired the “Catination” Storage Jar (April 12, 1836), an inscribed ceramic created by the American potter and poet David Drake (ca. 1800–ca. 1870s). Drake, who worked in the pottery district of Edgefield, South Carolina, is one of the best known—and one of the relatively few identified—Black artists and craftspeople who were forced to work under the horrific American slavery system. He is famous today because he signed many of his ceramics with his name—“Dave”—and, more rarely, with words and poems, thus preserving his identity for future generations in an era when the names and biographies of enslaved people rarely were recorded.

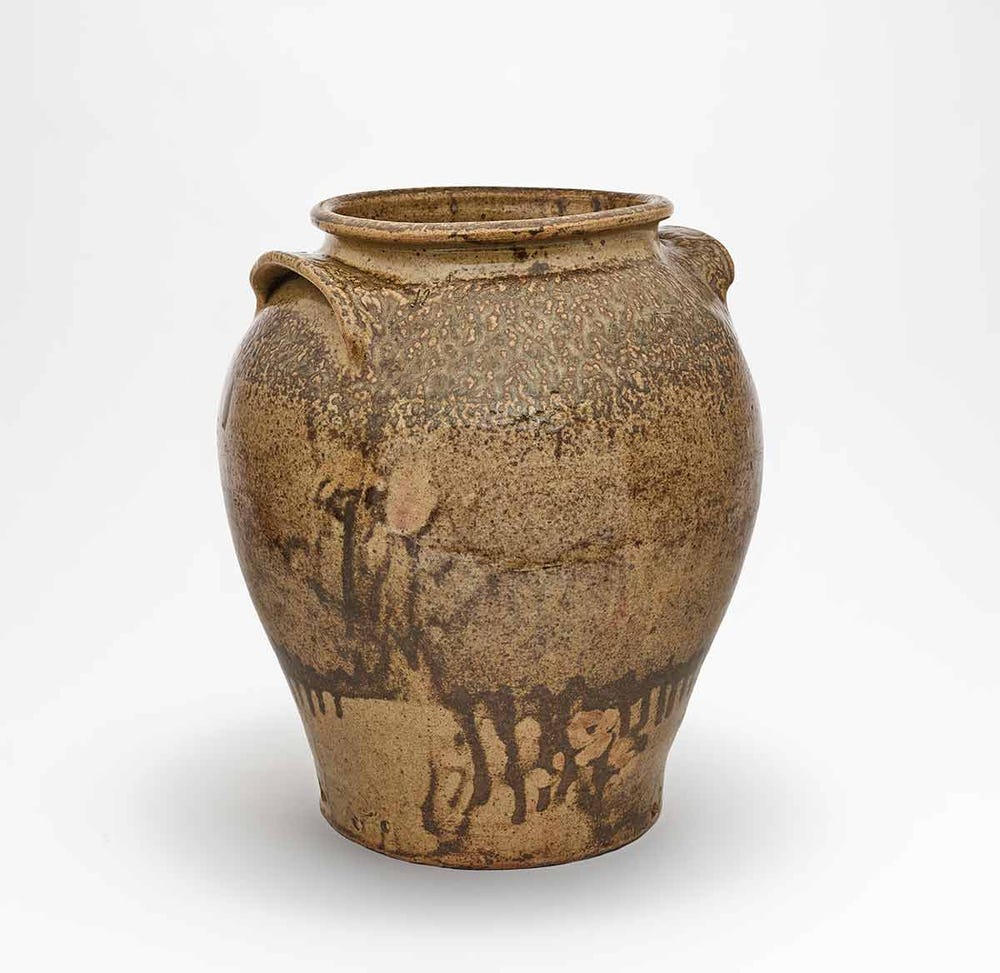

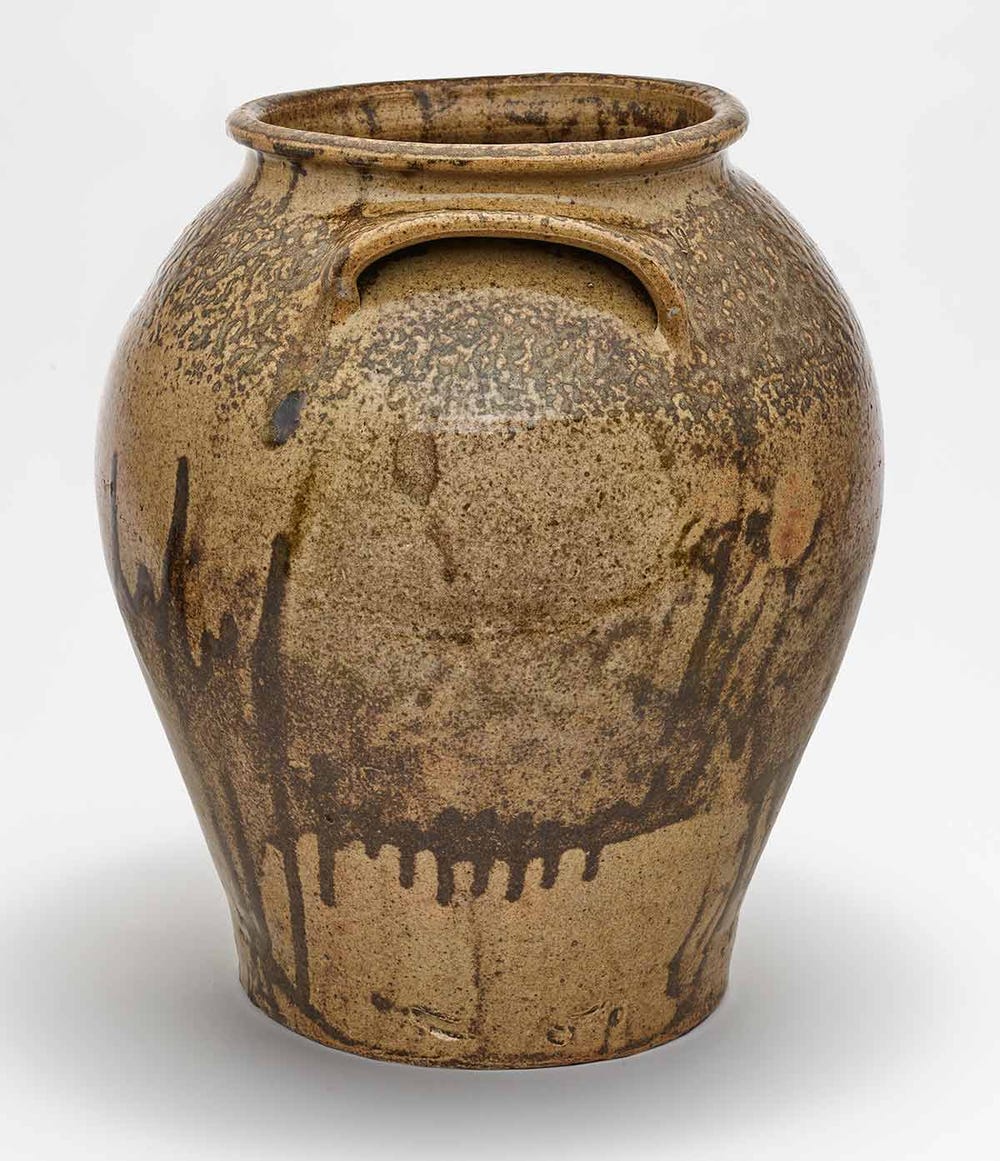

David Drake (ca. 1800–ca. 1870s) artist; Pottersville Stoneware Manufactory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, manufacturer, “Catination” Storage Jar, April 12, 1836. Glazed stoneware, height: 14 7/8 in. (37.8 cm); diameter: 12 5/8 in. (32.1 cm). Museum purchase, Calvin L. Malone American Arts and Crafts Fund, American Art Trust Fund, and American Decorative Arts Endowment Income Fund, 2020.57

Drake was born into slavery, possibly in or near the Edgefield district. He worked in Edgefield’s pottery district from sometime in the 1820s to ca. 1864. The region, rich with natural deposits of high-quality red and white clays, became known for its alkaline-glazed stoneware. Drake likely commenced his career as a potter at the Pottersville Stoneware Manufactory (founded ca. 1816), where he would have learned to dig the clay from stream beds, haul it to the pottery, and then grind it in a “pug mill” to remove air bubbles and ensure uniformity. Eventually, by emulating more experienced potters, Drake graduated to working as a turner. This involved throwing pots on a wheel, glazing them by dipping or ladling, and then firing them for twelve to eighteen hours at about 2,400 degrees in a “groundhog” kiln built into the side of a hill.

Despite having lost a leg—most likely in a train accident in the mid-1830s—Drake is believed to have turned, glazed, and fired thousands of stoneware objects, including storage jars, whiskey jugs, milk pitchers, and butter churns. He gained local renown for the quality of his ceramics, and also for their scale. Two of his storage jars, both dated May 13, 1859, measure over 2 feet tall and have an astonishing capacity of 40 gallons. Spectators often gathered to watch the artist at work. In 1859 the editor of the Edgefield Advertiser newspaper recalled local children watching Drake:

. . . as the clay assumed beneath his magic touch the desired shape of jug, or jar, or crock, or pitcher.

Remarkably, Drake inscribed some 40 of his approximately 175 surviving works with prose or poetry in an era when both reading and writing by enslaved people were widely prohibited. It is not known when or how Drake learned to read and write. Southern prohibitions against enslaved people obtaining an education, and against reading and writing in particular, were designed to prevent access to additional philosophical, religious, or intellectual arguments against slavery; to preclude the forging of passes and other documents that could pave the way to freedom in the North; and to hinder organized rebellions, like those associated with Denmark Vesey (1822) and Nat Turner (1831). In 1834, the South Carolina General Assembly passed a harsh anti-literacy law that further suppressed these essential human rights.

Possibly Drake learned to read in the wake of the Protestant Second Great Awakening religious revival that swept through South Carolina in the early nineteenth century. Adherents promoted the primacy of the Bible as the medium for personal salvation, prompting some enslavers to permit those they enslaved to read the Bible. Drake may have learned to write through Abner Landrum, founder of the Pottersville Stoneware Manufactory and the owner of the Edgefield Hive newspaper, which could have provided intentional or unintentional access to newpapers, books, paper, pens, and ink. Of Drake’s surviving ceramics, those that are inscribed with words and poems span the years 1834 to 1862. However, the tenuous status of his literacy under the oppressive slavery system is revealed by the long period from 1843 to 1848, during which he produced no inscriptions.

David Drake’s love of language, apparent in his ceramic poems, also was part of his public persona, as noted by contemporaries. In 1863, the editor of the Edgefield Advertiser newspaper recalled that Drake frequently deployed the greeting “How does your corporosity seem to sagatiate?,” meaning “How’s your body getting along?” Drake’s poems reflect on such diverse subjects as morality (Give me silver or; either gold / Though they are dangerous; to our soul); religion (I made this Jar all of cross / If you don’t repent, you will be lost); and romance (Another trick is worst than this / Dearest Miss, spare me a kiss). One of his most memorable and moving poems, inscribed on another stoneware jar in 1857, suggests that he was cruelly separated from his family: I wonder where is all my relation / Friendship to all—and, every nation.

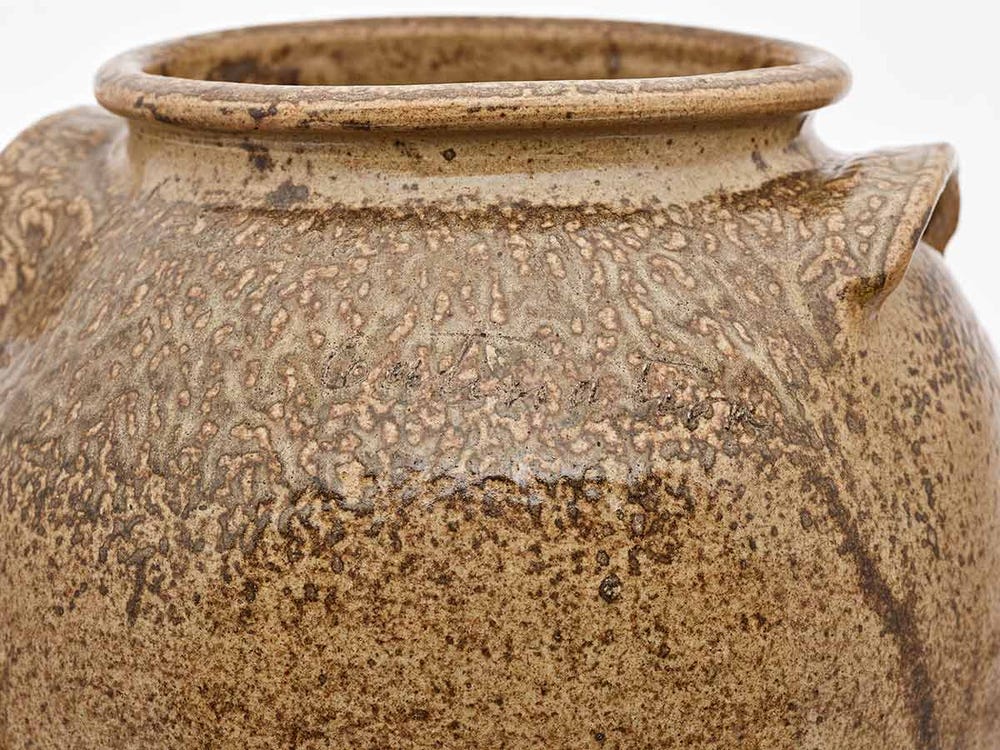

The Museums’ stoneware jar, most likely created at the Pottersville Stoneware Manufactory, is covered with runny umber/brown alkaline glaze, and is inscribed 12 April 1836 under the rim and Catination on the shoulder. Finger marks, most likely Drake’s, appear to be impressed in the glaze surface along the bottom edge. The jar is the eighth earliest known example by the artist, and the fourth earliest bearing an inscription. His precise intended meaning for the word Catination is not clear. The earliest of Drake’s extant inscribed jars, dated June 12, 1834, bears the related word Concatination. Both words are most likely variant spellings of concatenation (a series of interconnected things or events). Catenate (to connect or link in a series) is derived from the Latin root catena, or chain, thus infusing these inscriptions with powerful associations—not only with the most powerful symbol of human bondage, but also with family connections forged and broken.

Drake’s life epitomizes the horrors of the racist slavery system, but his work attests to the resilience and achievements of Black individuals despite these severe constraints. The Pottersville Stoneware Manufactory would have sold his storage jars as purely utilitarian products to be filled with food such as pork, beef, mutton, goat, bear, and lard (all mentioned in his poems). In defiance of anti-literacy laws, Drake’s transcendent act of adding inscriptions to his works transformed these functional ceramic objects into vessels that publicly declared—and carried—his authorship and artistry to a wider audience that included other enslaved Black individuals who aspired to read and write. Nearly two hundred years later, Drake’s inscribed ceramics serve as powerful symbols of personal and political resistance and cultural survival. The messages that they carry form an integral part of America’s many histories.

References

- Citations refer to: Leonard Todd, Carolina Clay: The Life and Legend of The Slave Potter Dave (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008).

- Images: David Drake (ca. 1800–ca. 1870s) artist; Pottersville Stoneware Manufactory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, manufacturer, “Catination” Storage Jar, April 12, 1836. Glazed stoneware, height: 14 7/8 in. (37.8 cm); diameter: 12 5/8 in. (32.1 cm). Museum purchase, Calvin L. Malone American Arts and Crafts Fund, American Art Trust Fund, and American Decorative Arts Endowment Income Fund, 2020.57

Text by Timothy Anglin Burgard, Distinguished Senior Curator and Curator-in-Charge, American Art Department.