Frida Kahlo, La Casa Azul, and National Pride

By Hillary Olcott

April 29, 2020

Every exhibition presented at the de Young museum is the culmination of months, and sometimes years, of passionate efforts of a large team of collaborators. Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving is no exception, and relied on an international team of scholars and curators to bring the exhibition to fruition. The exhibition was organized by guest curator Circe Henestrosa, independent fashion curator and Head of the School of Fashion at LASALLE College of the Arts in Singapore, with advising curator Gannit Ankori, an internationally renowned Frida Kahlo scholar and Professor of fine arts and women, gender, and sexuality studies at Brandeis University.

Coordinating curator of the de Young’s exhibition, Hillary Olcott, Associate Curator of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, details the journey of the exhibition from La Casa Azul to the de Young museum, and how Kahlo’s art and style were shaped by her love of her country and enduring national pride. This text is based in part on exhibition text written by guest curator Circe Henestrosa and advising curator Gannit Ankori.

Nickolas Muray, Frida on White Bench, New York City, 1939. Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

Recognized as one of the most significant artists of the twentieth century, Frida Kahlo is also one of the most recognizable, remembered and celebrated as much for her unique appearance as for her vivid paintings. The artist’s visage is now iconic, memorialized in her arresting self-portraits and in the myriad photographs taken of her throughout her life. Kahlo’s image is yet another of her artistic creations, as carefully constructed as one of her paintings. And while intentionally outwardly focused, as all appearances are, Kahlo’s style was also a reflection of her deeply held beliefs and personal experiences. Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving examines the ways in which disability, politics, gender, and national pride informed Kahlo’s life, her identity, and her mesmerizing and multilayered art.

The exhibition is centered on a collection of Kahlo’s personal possessions from her lifelong home, La Casa Azul, now the Museo Frida Kahlo in Coyoacán, Mexico. The material was locked away by Kahlo’s husband, Diego Rivera, after her death in 1954. Fifty years later, the staff of the Museo Frida Kahlo opened this time capsule and made an astounding discovery. They uncovered more than twenty-two thousand documents; six thousand photographs; and three hundred of Kahlo’s personal effects, including cosmetics, medical supplies, jewelry, and clothing. The materials provided new insights into Kahlo’s personal life and revealed the complex influences behind her now famous appearance.

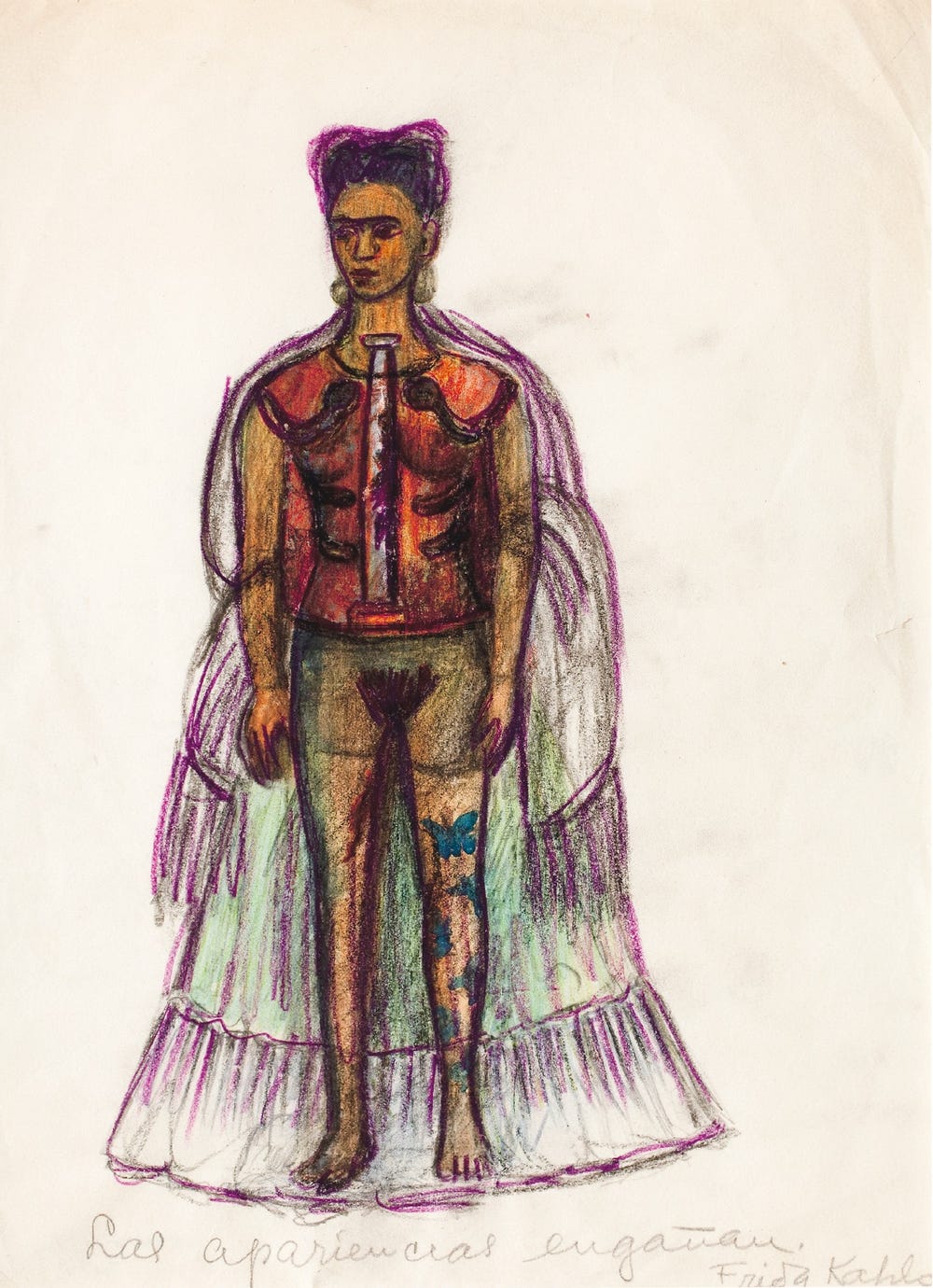

Frida Kahlo, Appearances Can Be Deceiving, no date. Charcoal and pencil on paper, 11 ⅜ x 8 ¼ in. (29 x 21 cm). Museo Frida Kahlo REPRODUCTION AUTHORIZED BY THE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF FINE ARTS AND LITERATURE, 2020

One of the articles found in the trove was a previously unknown self-portrait drawing (above). In it, Kahlo depicts herself, as she often did, in a floor-length flounced Tehuana skirt and fringed rebozo (shawl). But here, the garments are transparent, revealing Kahlo’s supportive back brace and her nude disabled body—her atrophied right leg, the result of childhood polio, and a disintegrating column representing her spine, which was damaged in a near-fatal bus accident at age eighteen. The voluminous clothing acts as mask, camouflage, and armor, concealing and protecting Kahlo’s vulnerable inner self. Echoing the imagery of the drawing, Kahlo titled the work Las Apariencias Engañan (Appearances Can Be Deceiving).

Inspired by this self-portrait, the Museo Frida Kahlo launched a study of Kahlo’s self-created sartorial identity and, in 2012, debuted the ongoing exhibition Las Apariencias Engañan: Los Vestidos de Frida Kahlo (Appearances Can Be Deceiving: Frida Kahlo’s Wardrobe), curated by Circe Henestrosa. The Victoria & Albert Museum in London expanded the presentation into the critically acclaimed blockbuster exhibition Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up (2018) co-curated by Henestrosa and Claire Wilcox, which then traveled to the Brooklyn Museum in New York (2019). These projects—curated by Henestrosa in collaboartion with Gannit Ankori—have in turn inspired the exhibition at the de Young museum in San Francisco, a city that was beloved by Kahlo and that played an important role in shaping her identity and artistic path.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving offers visitors the opportunity to explore and appreciate the artist’s diverse modes of creative expression side by side. It features a poignant selection of Kahlo’s belongings from the 2004 discovery, including notated family photographs, customized orthopedics, and twenty-two vibrant ensembles. The belongings are displayed alongside photographs of Kahlo taken by her friends and loved ones, themselves renowned artists. Together, this material provides an intimate look at the artist’s personal life, and reveals the creativity and care with which she composed her celebrated style.

Installation of Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving at the de Young museum, with Kahlo’s ensembles from the Museo Frida Kahlo.

But it is Kahlo’s own works of art that reveal the depth and complexity behind her appearance. Hardly superficial, her style of self-depiction was part of a richly symbolic visual language that she used to convey her innermost thoughts and emotions. The de Young museum’s presentation features more than thirty of Kahlo’s works from institutions and private collections in the United States and Mexico: paintings; drawings; and her sole examples of fresco, collage, and lithography. Many, including rarely shown paintings and never-before-seen drawings, are unique to this presentation of the exhibition. Presented with Kahlo’s belongings, the works reveal the intersections between Kahlo’s life and art and explore the complex forces that contributed to her self-fashioned identity.

One of the factors that greatly influenced Kahlo was her deeply held national pride. Born in 1907, Kahlo was a child of the Mexican Revolution and spent her formative years witnessing the great turbulence, transformation, and reinvention of her country. She so identified with the revolutionary cause that she changed her birth year to 1910, aligning her own genesis with that of her reformed country. Kahlo communicated her connection to Mexico through both her art and appearance. In the earliest painting in the exhibition, Pancho Villa and Adelita (1927), Kahlo depicts herself as the protagonist of a famous revolutionary ballad about a brave and beautiful soldadera. While she paints her Adelita wearing a European-style gown, Kahlo often chose to wear garments that were distinctly Mexican: floor-length dresses, necklaces made of pre-Hispanic greenstone beads, and vibrant fringed rebozos.

Frida Kahlo, Frieda and Diego Rivera, 1931. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 31 in. (100 x 78.7 cm). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Albert M. Bender Collection, gift of Albert M. Bender © 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, alc. Cuauhtémoc, C.P. 06000, Mexico City. Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo: Ben Blackwell

Kahlo first depicts herself dressed in this way (above) in the double portrait Frida and Diego Rivera (1931), reunited in the exhibition with other works that Kahlo made while she lived in San Francisco from 1930 to 1931. Kahlo’s choice of clothing was deliberate and became integral to her identity and expression of Mexican pride. She adopted elements of dress worn by women in Tehuantepec—embroidered huipiles (tunics), long gathered enaguas (skirts), and white cotton holanes (flounces)—as a nod to the matriarchal Tehuana culture and to her own Oaxacan roots. In two of her works, My Dress Hangs There (1933) and Memory or The Heart (1937), both included in the exhibition, Kahlo demonstrates her connection to her chosen style. In both instances she depicts her Tehuana outfit (which is also on view in the exhibition) as a surrogate for her absent self. Here, the Tehuana dress is not her camouflage but her avatar, an extension or alternate version of herself. The exhibition also includes one of Kahlo’s final paintings, Self-Portrait with Diego on My Breast and Maria on My Brow (1954, unfinished), in which she portrays herself in an embroidered huipil and a heavy beaded necklace, situated in the colorful mountainous landscape of central Mexico. While the unsteady brushstrokes demonstrate Kahlo’s waning health, the painting is a testament to her lifelong commitment to her sartorial identity and to enduring national pride.

Nickolas Muray, Frida with Olmeca Figurine, Coyoacán, 1939. Color carbon print, 10 3/4 x 15 3/4 in. (27.3 x 40 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of George and Marie Hecksher in honor of the tenth anniversary of the new de Young museum. 2018.68.1. © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

Kahlo communicated her love of Mexico in other ways besides her dress. With as much care as she put toward her own appearance, Kahlo transformed the interior and exterior spaces of her home into a celebration of Mexican creative expression. She and Rivera moved into Kahlo’s childhood home in Coyoacán in the 1930s and redecorated the house and garden, transforming it into a veritable microcosm of Mexico. They planted cacti, citrus trees, and flowering plants in the garden and adopted monkeys, parrots, and hairless xoloitzcuintli dogs as pets. The couple filled their home with beautiful objects from across the country—polychrome ceramics, folk art, and pre-Hispanic sculptures—and painted the walls a brilliant blue, inspiring the moniker “La Casa Azul.”

Installation of Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving at the de Young museum, showing a selection of pre-Hispanic objects from the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Just as the house served as a creative outlet for Kahlo, it also offered her boundless sources of inspiration. Kahlo and Rivera were avid collectors of pre-Hispanic art and amassed thousands of sculptures from ancient sites across Mexico. They found these objects aesthetically appealing and felt that the sculptures demonstrated the breadth of Mexico’s rich and diverse cultural past. In two paintings included in the exhibition, Survivor (1938) and Still Life (I Belong to Samuel Fastlicht) (1951), Kahlo carefully depicts sculptures from her vast collection of pre-Hispanic art. In the latter, a ceramic dog from a Colima tomb takes the place of a skull in a vanitas still life. In the former (below), a ceramic Colima ballplayer is the sole inhabitant of a deserted and desert-like landscape. By featuring these sculptures as the primary subjects of her paintings, Kahlo highlights her country’s long history of creative expression and aligns herself with the great artists of Mexico’s ancient past.

Frida Kahlo, Sobreviviente (Survivor), 1938. Oil on metal, 6 ½ x 4 ¾ in. (16.5 x 12 cm). Colección Pérez Simón, Mexico. Photo: Rafael Doniz REPRODUCTION AUTHORIZED BY THE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF FINE ARTS AND LITERATURE, 2020

Text by Hillary Olcott, Associate Curator of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, based in part on exhibition text written by advising curator Gannit Ankori and guest curator Circe Henestrosa.

Learn more about Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving at the de Young.