Every exhibition presented at the de Young museum is the culmination of months and sometimes years of passionate efforts of a large team of collaborators. Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving is no exception, and relied on a group of diverse, international curators to bring the exhibition to fruition. Advising curator of the exhibition, Gannit Ankori (Professor of Art History and Theory and Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Brandeis University) recounts the special time that Frida Kahlo spent in San Francisco, including the personal connections she made while living here, the fellow artists she inspired, and the effects the “beautiful city” had on her and her art.

Victor Reyes, Wedding portrait of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, 1929. Photograph, gelatin silver print with hand-applied transparent watercolor, Sheet: 7 1/16 x 4 15/16 in. (18 x 12.6 cm). Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Anonymous gift, 2016.112 Photograph © 2020 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Frida Kahlo stepped into the limelight in 1929 when she married the Mexican muralist, Diego Rivera. She was 22. He was 43. He was a world renowned artist celebrity; the marriage certificate identifies her as a housewife.

A year after their marriage, Rivera was commissioned to paint murals in San Francisco, New York, and Detroit, and the newlyweds traveled to “Gringolandia” as Kahlo called the US. Rivera also had a solo exhibition at the newly founded Museum of Modern Art in New York. Kahlo was perceived as Rivera’s exotic third wife, who “dabbles in art” and a “colorful” Mexican woman.

This was Kahlo’s very first trip outside her native Mexico, and her letters home express palpable excitement and anticipation. When they arrived in San Francisco in November 1930, they resided on 716 Montgomery Street, near the artists William Gerstle and Ralph Stackpole, who helped secure Rivera's commission to paint a mural at the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the San Francisco Art Institute. Rivera eventually painted additional work, surrounded by a close-knit circle of admiring artists, benefactors, and friends. Both he and Kahlo fell in love with the city and, once again, with each other.

Upon her arrival, Kahlo sent her mother two postcards and wrote an exuberant letter to her papacito lindo:

San Francisco is very beautiful. Our way here was also very beautiful. For the first time I got to see the Ocean, and I loved it! The city is in a beautiful location, from everywhere you can see the sea. The bay is beautiful and ships arrive from China and from everywhere in the Orient.

Kahlo reported to her mother that Rivera was “good to me (so far)” and much less busy than in Mexico, so they spent more time together, to her delight. They explored Stanford University, Berkeley, Fairfax, and travelled to Los Angeles as well.

Kahlo was fascinated by the multiple ethnic neighbourhoods that comprised San Francisco and its vicinity, and wrote to her family about this with great enthusiasm. She and Rivera lived a few blocks from Chinatown and she was mesmerized by what she saw there, as she wrote to her father:

Imagine, there are 10,000 Chinese here, in their shops they sell beautiful things, clothing and handmade fabrics of very fine silk. When I return I'll tell you all about it in detail.

Rebozo with rapacelo (knotted fringe); silk skirt with Chinese embroidered panel and holán (ruffle). Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. Photograph: Javier Hinojosa

The gringas really like me a lot and pay close attention to all the dresses and rebozos that I brought with me, their jaws drop at the sight of my jade necklaces.

The letters reveal that Kahlo was becoming aware of the power of distinct ethnic costumes. This may have prompted her to cultivate further her exotic Mexican persona. Abroad, her indigenous Mexican costumes and sartorial flair were a unique and much-admired phenomenon. “The gringas love me,” she wrote to her family, describing their admiration for her Mexican dresses, shawls, and jewellery. She thrived in the spotlight and relished her new-found freedom, as she posed for the best photographers, befriended a host of fascinating people from all walks of life, and explored a new world with joy and curiosity.

— Edward WestonI photographed Diego again, his new wife—Frieda—too: she is ... petite, a little doll alongside Diego, but a doll in size only, for she is strong and quite beautiful, shows very little of her father's German blood. Dressed in native costume even to huaraches, she causes much excitement on the streets of San Francisco. People stop in their tracks to look in wonder.

Edward Weston, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, 1930. Gelatin silver print, 9.6 x 7.5 in. (24.3 x 19 cm). Collection Center for Creative Photography, Edward Weston Archive, 81.276.1 © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Many of the people she met maintained a lively correspondence with her even after she left San Francisco, later visiting her in Detroit and Mexico, and continuing to care about her very deeply.

Frida Kahlo, Portrait of Dr. Leo Eloesser, 1931. Oil on Masonite, 331/2 x 231/4 in. (85.1 x 59.1 cm). University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, Dean’s Office at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center © 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, alc. Cuauhtémoc, C.P. 06000, Mexico City. Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

A few friendships she forged—like her deep relationship with the artist Emmy Lou Packard and the thoracic surgeon and medical scholar Dr. Leo Eloesser—were sustained until her death. Eloesser in particular played a pivotal role in Kahlo’s life at significant medical and marital junctions. They met on November 9, 1930, and the next day Frida wrote to her mother raving about the doctor. His fluency in Spanish, the way he took care of her, and her complete confidence in him—as medical adviser and trusted friend—were transformed into a friendship of 24 years. Kahlo expressed her gratitude by painting a loving portrait of her friend (Portrait of Leo Eloesser, 1931). In 1940 she gave him the stunning Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leo Eloesser (below) that contains the inscription: “I painted my portrait for Dr. Leo Eloesser, my doctor and best friend, with all my love, Frida Kahlo.” In the 1950s, she painted a still life for her queridísimo Doctorcito.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Dr. Leo Eloesser, 1940. Oil on Masonite, Private Collection © 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, alc. Cuauhtémoc, C.P. 06000, Mexico City. Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

While Rivera was painting his grand murals in San Francisco, Kahlo devoted time to painting as well, and gradually began to take her art more seriously. Her extraordinary intellectual, artistic, and personal growth in San Francisco was captured by one of her new friends, the writer John M. Weatherwax. In 1931, Weatherwax completed a dozen versions of an unpublished play and short story, both titled The Queen of Montgomery Street. In these manuscripts, the much-adored “Queen Frieda” comes to life: her unique persona and dramatic appearance captivate all who come under her spell. Kahlo’s childlike exuberance, playfulness, and humour were among her most enduring characteristics, noted by friends, even as her life force waned. Her love of dolls, toys, games, and puppets can be sensed as one reads her letters, listens to her friends reminiscing, or observes the photographs and objects she left behind.

The Queen has been laughing and clapping her hands…Everyone has been looking at her. She is bewitching in her long, high-waisted grass-green dress. Over her shoulders is a bronze open-work shawl. About her neck is a heavy jade-green chalchihuitl necklace. Her black hair is parted in the middle and drawn into a little knot at the back of her neck. Her cheeks and lips have just the right amount of rouge. Her feet are still in guaraches. Glowing, she returns to her seat.

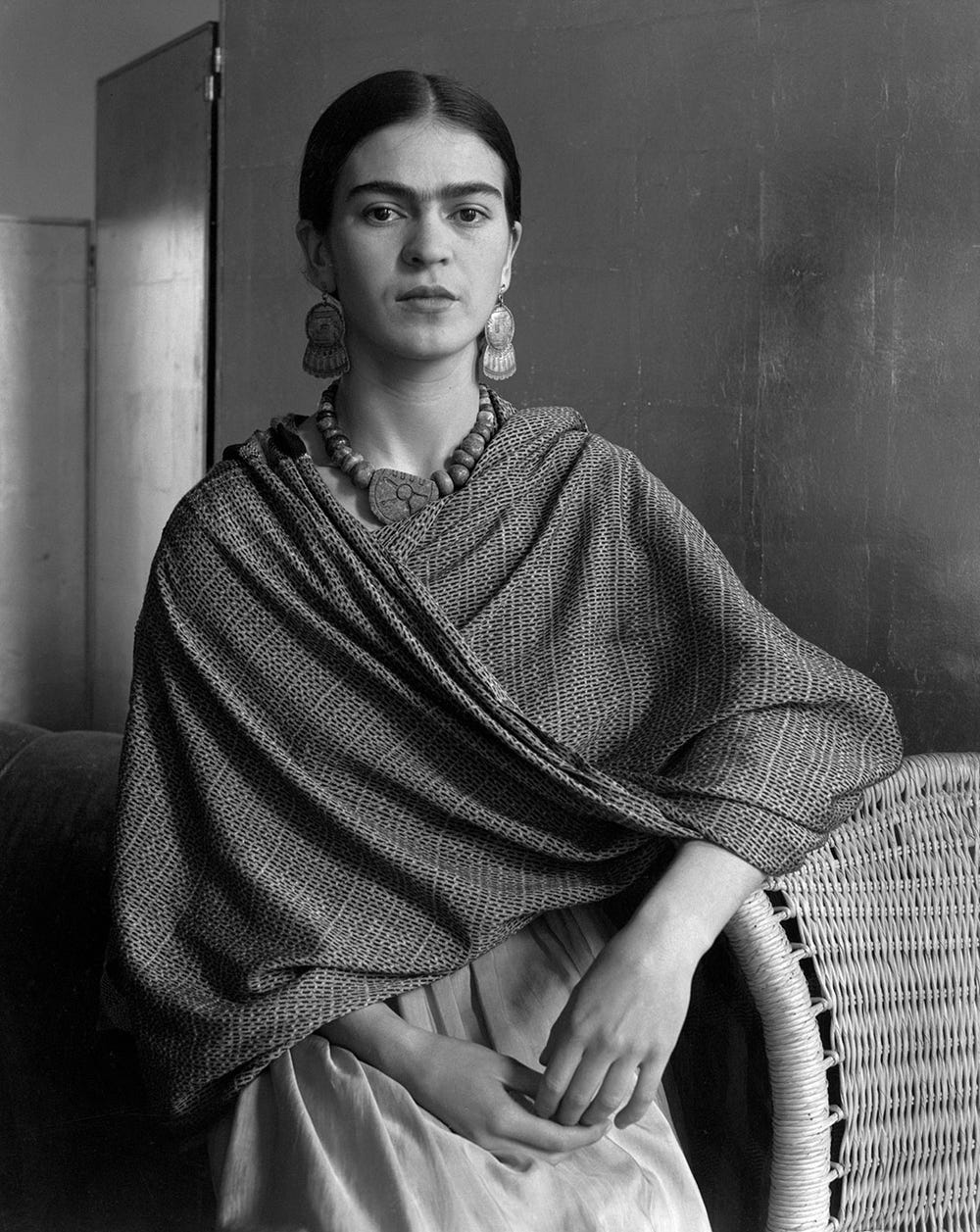

Imogen Cunningham, Frida Kahlo, Painter and Wife of Diego Rivera, 1931. Gelatin silver print, 11.9 x 9.5 in. (30.1 x 24 cm). Center for Creative Photography, Gift of Ansel and Virginia Adams, 76.14.9 © 2020 Imogen Cunningham Trust

Kahlo’s amorous relationship with her husband is also vividly described throughout Weatherwax’s texts. He wrote of them:

They seem to be completely happy. She in her twenties, he in his forties. She a German-Mexican, he ever so typically Mexican. He gets up... putting an arm around the Queen. He bends down to her. His lips move out, making a delicate little noise. The Queen laughs, hugs him, and kisses him on the neck. Don Diego straightens up, slowly. The Queen is still clinging to him, her feet now twelve inches from the floor. She bites his ear, laughs, and lets go. Arm in arm they turn the end of the corridor, unlock another door, and enter the Royal Studio.

Weatherwax also provides details about Kahlo’s portrait painting:

The Queen is already hard at work. The poser doesn't crack a smile, doesn't even look up when the door opens. Frieda works like lightning. She has done many oils. If she wished, she could have a one-man exhibit in New York at any time... At last Don Diego comes home... The Queen throws her arms around his neck, laughing gleefully. Astonishment, fear and joy struggle in Don Diego's face. The poser bows good-bye. The King and the Queen go to Frieda's gigantic easel. Don Diego looks long and soberly at his wife's work. 'Bueno', he says. After a while he adds in Spanish, “A pure and strong woman's spirit is as precious as the light of the stars.’

While Weatherwax was composing his tender tale of Queen Frieda and King Diego, Kahlo painted a slightly more ambiguous version of her marriage (below). The inscription painted above the double portrait reads:

Here you see us, myself Frieda Kahlo together with my beloved husband Diego Rivera. I painted these portraits in the beautiful city of San Francisco California for our friend Mr Albert Bender, and it was the month of April 1931.

Frida Kahlo, Frieda and Diego Rivera, 1931. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 31 in. (100 x 78.7 cm). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Albert M. Bender Collection, gift of Albert M. Bender © 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, alc. Cuauhtémoc, C.P. 06000, Mexico City. Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo: Ben Blackwell

Kahlo herself, the artist who painted the image, is not presented as a painter at all. Rather, it is Rivera who is portrayed as the great artist, holding the attributes of the painter (palette and brushes) in his right hand. Kahlo, in contrast, holds onto her husband, defining herself not as a painter but as “the painter’s little wife.”. She displays herself in colorful native garb, adorned with a red rebozo and jade Aztec beads—the paradigmatic Mexican woman. Moreover, Kahlo’s manner of painting this work—the stiff pose, awkward rendering of the feet, and affinity with colonial portraiture—emulates the style of an amateur painter. She conceals her sophistication behind a mask of naivety and camouflages her position as a painter by espousing the subordinate role of the doting wife. Ironically, Kahlo deliberately based this Mexican, pseudo-naive work on a well-known European precedent, Jan van Eyck’s depiction of a marriage, his Arnolfini Portrait of 1434. She kept a reproduction of this work in her studio, among numerous other books and documents that reflected her vast knowledge and erudition. Like van Eyck, she emphasized the importance of the marriage bond by placing the joined hands of husband and wife at the very center of the composition. The exact positioning of Rivera’s hand and head, however, subtly conveys his aloofness and less-than-active participation in this union.

Text by Gannit Ankori, Professor of Art History and Theory and Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Brandeis University. Excerpted from her book Critical Lives: Frida Kahlo.

Learn more about Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving at the de Young.