Frida Kahlo’s Construction of Identity: Disability, Ethnicity, and Dress

By Circe Henestrosa

March 18, 2020

Every exhibition presented at the de Young museum is the culmination of months and sometimes years of passionate efforts of a large team of collaborators. Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving is no exception, and relied on a group of diverse, international curators to bring the exhibition to fruition. Guest curator of the exhibition Circe Henestrosa, independent curator and Head of the School of Fashion, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore shares the story about the rediscovery of Kahlo’s personal items at the Blue House in Mexico City in 2003, and shares insights into Kahlo’s construction of her identity.

L: Nickolas Muray, Frida Kahlo, 1939, New York City, 1939. 18.5 x 11.4 in. (47 x 29 cm). The Heckscher Family Collection © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives. R: Rezbozo and cotton huipil, silk skirt with woven velvet floral motifs. Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. Photograph: Javier Hinojosa

In late 2003, permission was granted to access the bathroom adjacent to Frida Kahlo's bedroom at her former home, the Blue House, in Mexico City, in which her belongings had been stored since Rivera's death in 1957. When the door was unlocked, our eyes were opened again to the messages Kahlo's clothes conveyed, forging an immediate connection with Kahlo as a person. The clothes in Kahlo's wardrobe teach the modern eye something new about the artist herself—something of her essence that had been misplaced by time. Her vibrant collection was composed mostly of traditional Mexican pieces from Oaxaca and beyond. There were also garments from Guatemala and China, a collection of European and American blouses, as well as jewellery, accessories, orthopaedic devices, shoes, and make-up. In addition, there were 16 Tehuana blouses and 25 Tehuana skirts, some of them sewn and personalized by Kahlo herself.

A photograph of Kahlo's maternal family (below) was also found inside the bathroom, an image that has become another important source of inspiration for Kahlo scholars: it shows Kahlo's mother fully dressed in the Tehuana tradition, revealing Kahlo's relationship with this attire long before meeting Rivera. As Mexican anthropologist Martha Turok later observed: “the myth that Diego encouraged her to assume this attire began to crumble with (this) discovery.”

Ricardo Ayluardo, Mama (Oaxaca) Matilde Calderón, 7 years old, 1890. Frida Kahlo & Diego Rivera Archives. Bank of Mexico, Fiduciary in the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museum Trust

Kahlo was, and is, the very model of the bohemian artist: unique, rebellious, and contradictory; a cult figure who has been appropriated by feminists, artists, fashion designers, and popular culture. She continues to cause sensation with her enigmatic coquettish gaze and deep, dark brown eyes that seem to hold the viewer for a moment too long. At once commanding yet fragile, instantly recognizable with her trademark unibrow and bold Tehuana dress, she assembled all the appropriate elements of an icon—the ultimate modern-day icon. Some of her closest friends, such as the painter Lucile Blanch, recalled that “Frida had an aesthetic attitude about her dress.” Kahlo's biographer Hayden Herrera described how Kahlo would take special care in choosing each one of her garments, styling herself from head to toe with the most beautiful silks, lace, shawls, and skirts. And, during a visit to San Francisco in 1930, children in the street would ask her “where is the circus?” but she would just smile graciously and carry on walking.

Nickolas Muray, Frida with Olmeca Figurine, Coyoacán, 1939. Color carbon print, 10 3/4 x 15 3/4 in. (27.3 x 40 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of George and Marie Hecksher in honor of the tenth anniversary of the new de Young museum. 2018.68.1. © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

As a woman, an artist, and an icon, Kahlo has achieved rare, almost universal, acclaim. In a society often obsessed with tearing down the walls of the private self, Kahlo is the very embodiment of the ethos du jour. The choices she made reflected an intuitive ability to use a bold visual identity to situate herself in the art world at a time when women artists were fighting to win recognition for their work, and, in her case, recognition as an autonomous figure distinct from her famous husband. For someone whose entire oeuvre was “heart on sleeve,” why would her wardrobe be any different? As Herrera has pointed out:

Kahlo is an alluring victim, for those drawn to notions of victimization and sadomasochism. On the other hand for those interested in psychological health, terminal illnesses and appalled by drug abuse, the gritty strength with which she endured her pain is salutary.... Although her paintings record specific moments in her life, all who view them feel Kahlo is speaking directly to them.

However, with this universal acceptance, something has been lost. The links to Kahlo's heritage and political beliefs have been superseded by her beatification. It is the aim of my research to recapture this lost message, which can be visually expressed through dress. As the art historian Oriana Baddeley has explained:

Kahlo's popularity (means) her 'Mexican-ness' has become a stylistic gloss, decorative, colourful, pretty ... the colonised body which Kahlo clothed in revolutionary idealism has lost its function as a symbol of nationhood, becoming instead an icon of female suffering. What is obscured by this process is that it was through clothing, in both art and life that Kahlo attempted to redress the wrongs of history.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait, 1948. Oil on Masonite, 20 x 15.6 in. (50 x 39.5 cm). REPRODUCTION AUTHORIZED BY THE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF FINE ARTS AND LITERATURE, 2020

It has been suggested by various scholars that Kahlo adopted the Tehuana dress to please her husband, who admired powerful Zapotec women. But I would argue that her use of a hybrid dress was a calculated stylization. Kahlo was able to perceive the semiotic quality of clothing, and the ease with which it could be understood by others. Kahlo used traditional dress to strengthen her identity, while simultaneously reaffirming her political beliefs.

The discovery of the photograph of Kahlo's maternal family encourages us to look anew at other defining moments in Kahlo's life, strengthening the argument that her choice to wear Mexican traditional dresses was not merely to please Rivera, or at the very least, not for that reason alone. Kahlo's choice of style and dress was rooted in an ongoing search for self-affirmation. The quest for apparel that would help her deal with the impact of ill-health was possibly a driving force that would eventually lead her back to her mother and to the familiarity of the stylistically rigid and traditional forms of the Tehuana. Her adoption of this dress was conscious and considered, both distracting and purposeful: a complex combination of her communist ideology, her Mexican-ness, constructed from her personal traditions and as a reaction to her disabilities.

Kahlo was aware of the power of clothes from a very young age. But she was equally aware of her fragmented body after contracting polio at the age of six and suffering a near-fatal accident at the age of 18. These incidents caused her lasting pain and formed the core subject of her art, but they also informed her personal style. As a result of the polio, she was left with a wasted and shorter right leg, which is one of the reasons why she often wore long skirts. From a young age, she would wear three to four socks on her thinner calf and also wore shoes with a built-up heel to mask her asymmetry.

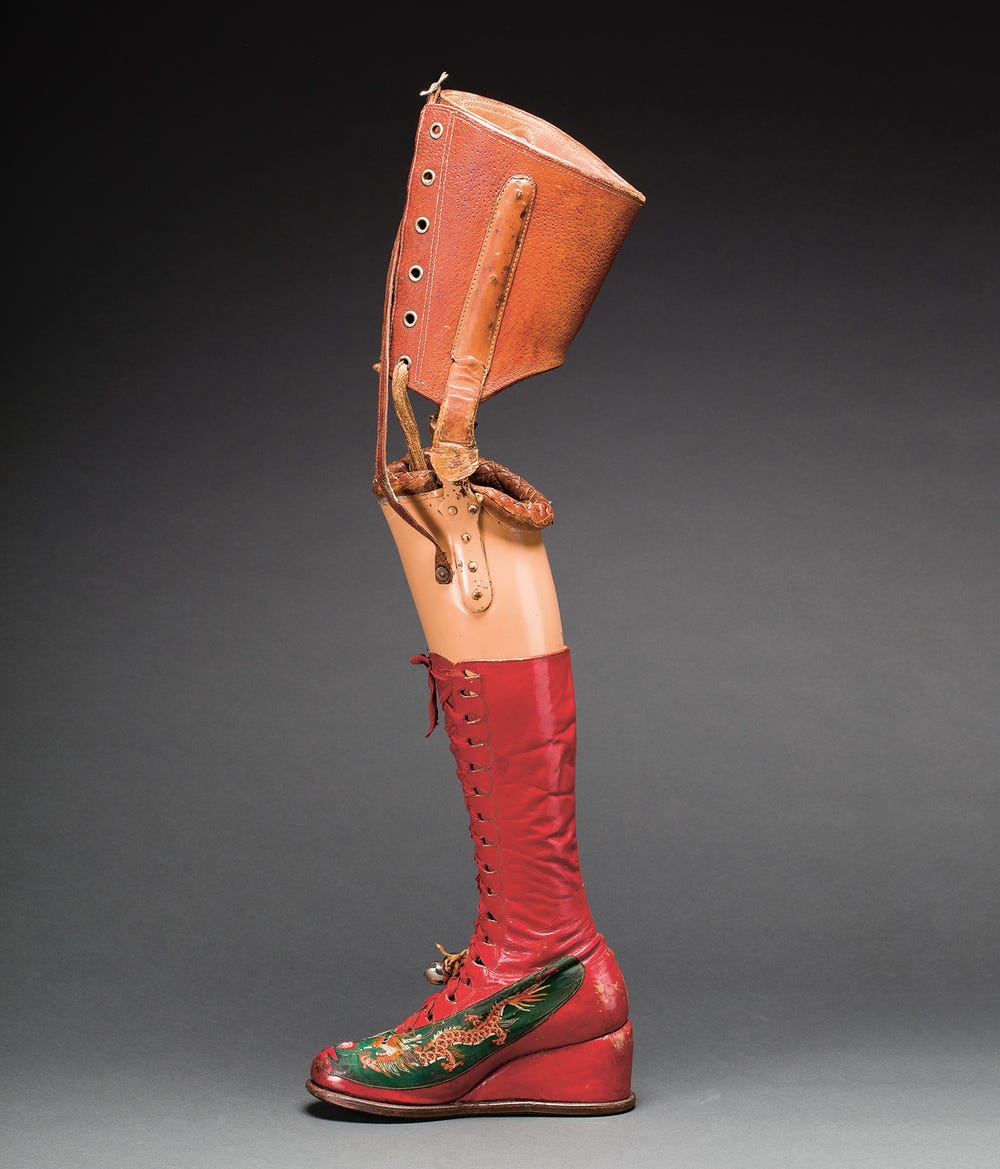

Prosthetic leg with leather boot. Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. Photograph: Javier Hinojosa

Kahlo would carefully decorate her shoes with bows, pieces of silk embroidered with Chinese dragon motifs, or add little bells. Her footwear has a distinctly contemporary and avant-garde feel; a pair of lilac Converse style shoes demonstrates Kahlo's visionary aesthetic. A series of three identical red boots decorated with green Chinese embroidery match her prosthetic leg—they are arguably the most enigmatic and modern objects in the collection.

Evidence of the trauma Kahlo suffered is also evident in her orthopaedic devices. Kahlo's relationship with the corset was one of support and need—her body was dependent on medical attention—but also one of rebellion. Far from allowing the corset to define her as an invalid, Kahlo decorated and adorned her corsets, making it appear as though she had explicitly chosen to wear them. She included them in the construction of her style as an essential wardrobe item, and they functioned as her second skin. Her self-fashioning was not purely visual; most of her clothes were made of lightweight fabrics such as cotton and silks, which she chose for comfort. The breathability of these fabrics allowed her to wear corsets comfortably beneath beautiful Mexican blouses.

The heavily adorned and fragmented composition of the traditional Tehuana dress enabled Kahlo to manipulate the geometry of her body's proportions. Comprising three key elements; below, a long skirt—the enagua—with a gathered waistband; above, a square-cut geometric blouse—the huipil; and, lastly, a hairstyle composed of braiding and flowers (as in the painting above), Kahlo's stylistic interpretation of the Tehuana attire allowed her to draw attention to her head and torso, shifting the viewer's focus away from her lower body. The huipil, thanks to its geometric construction, helped Kahlo to look taller and, when she was seated, prevented the fabric from bunching up around her waist, thereby avoiding discomfort. Kahlo always worked within this tripartite template, even when combining European pieces with Tehuana dress.

Nickolas Muray, Frida in New York, New York City, 1946. © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

Kahlo's response to her disability illuminates the complex relationship between fashion and dress, functionality and self-expression; she bares all and hides all through her personal styling. According to sociologist Joanne Entwistle:

Fashion and dress have a complex relationship to identity: on one hand the clothes we choose to wear can be expressive of identity, telling others something about our gender, class, status and so on; on the other, our clothes cannot always be ‘read,’ since they do not straightforwardly ‘speak’ and can therefore be open to misinterpretation.

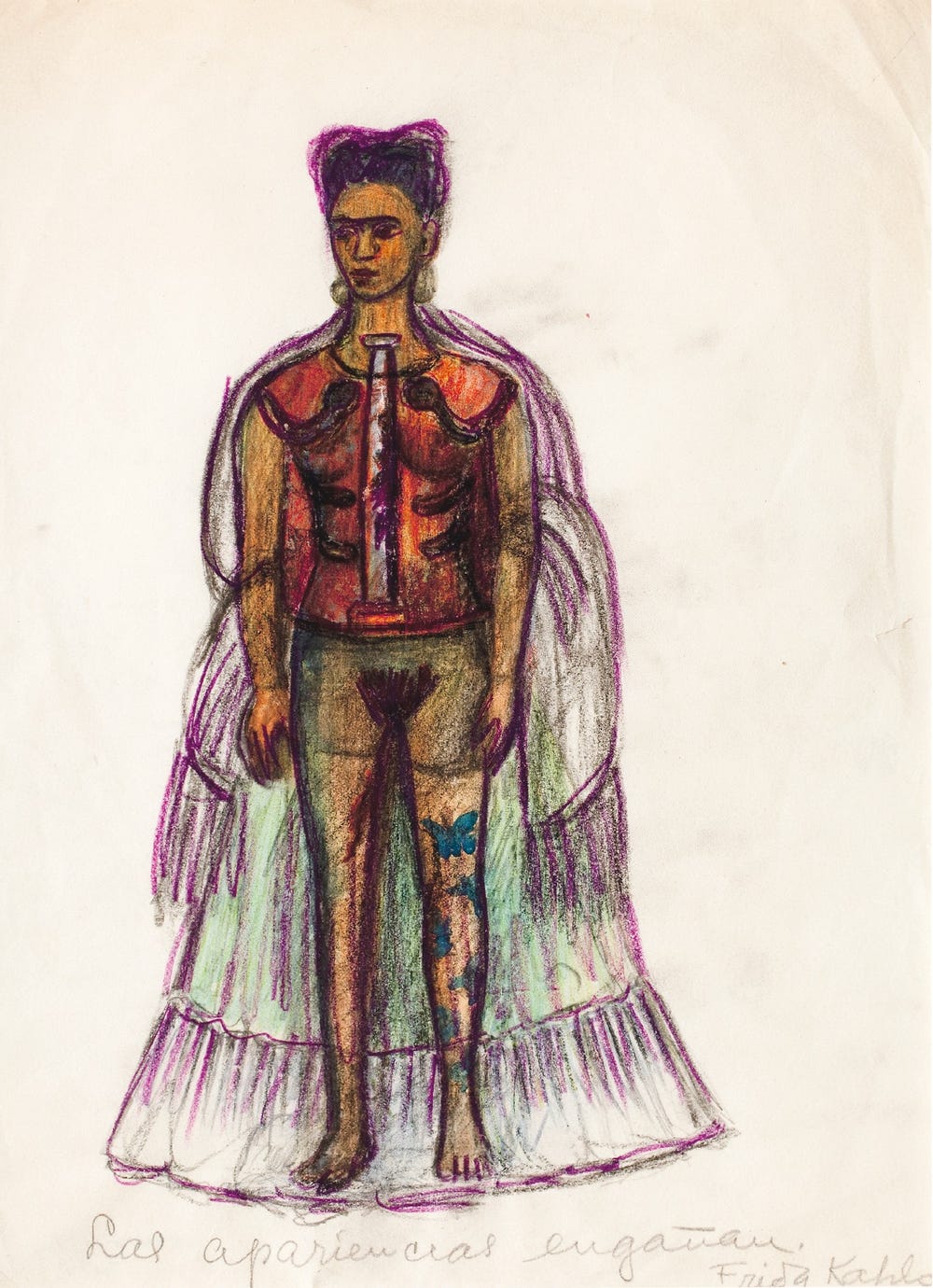

This tension between clothes as revealing and clothes as concealing of identity has also been addressed by sociologists Richard Sennett and Barbara Finkelstein, who analyzed the ways in which identity is inherent in appearance and yet, can also be hidden behind a disguise. While Kahlo would style herself from head to toe with ethnic dress, allowing her disability to be covered, she was prepared to uncover her disability unflinchingly through her art. For example, in a drawing inscribed Appearances can be Deceiving (below), Kahlo depicts her fractured body hidden beneath a transparent skirt, blouse and rebozo, covering and uncovering perhaps her greatest creation: herself.

Frida Kahlo, Appearances Can Be Deceiving, no date. Charcoal and pencil on paper, 11 ⅜ x 8 ¼ in. (29 x 21 cm). Museo Frida Kahlo REPRODUCTION AUTHORIZED BY THE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF FINE ARTS AND LITERATURE, 2020

Placing disability at the forefront of my interpretation of Kahlo's personal style provokes questions about disability as part of human experience, its relationship to fashion, dress, femininity, and identity. It was through her self-portraits and the adoption of traditional Mexican dress that Kahlo was able to examine her life, her political views, her health struggles, her accident, her turbulent marriage, and her inability to have children. When Kahlo's wardrobe was discovered, I felt I had met her personally for the first time, understanding her through her unique wardrobe, and viewing her through the lenses of disability, ethnicity, fashion, and dress. It has been a long personal journey, from dancing as a child at my great-uncle's birthday celebration, a Tehuantepec vela, to my own Tehuana wedding at which I danced the traditional zandunga, with my skirt swaying and flowers in my hair. My research has been an attempt to rediscover this powerful and fascinating woman, to truly understand her through her unique wardrobe. Through her clothes, the specter of Kahlo's essence is conveyed to us anew. We do not stare or observe—we meet, face-to-face.

Toni Frissell, Frida Kahlo (Senora Diego Rivera) standing next to an agave plant, during a photo shoot for Vogue magazine, "Senoras of Mexico," 1937 Negative, nitrate. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Toni Frissell Collection, LC-DIG-ds-05052

In this text, disability is defined according to the World Health organization’s definition. “Disabilities is an umbrella term, covering impairments, activity limitations, and participatory restrictions. An impairment is a problem in body function or structure; an activity limitation is a difficulty encountered by an individual in executing a task or action; while a participatory restriction is a problem experienced by an individual in involvement in life situations.”

Text by Circe Henestrosa, independent curator and Head of the School of Fashion, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore. Excerpted from “Appearances Can Be Deceiving - Frida Kahlo’s Construction of Identity: Disability, Ethnicity and Dress” in Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up (V&A Publishing, London). Available for purchase from the Museum Stores.

Learn more about Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving at the de Young.

Further Reading

- Gannit Ankori, "Frida Kahlo: The Fabric of her Art," in Frida Kahlo, Emma Dexter and Tanya Barson (eds.), London, Tate Publishing, 2005

- Oriana Baddeley, ‘“Her Dress Hangs There”: De-frocking the Kahlo Cult’, Oxford Art Journal, vol. 14, no.1, 1990

- Alicia Azuela de la Cueva, et al., Tesoros de la casa Azul, Frida y Diego, Mexico City, 2007

- Joanne Entwistle, The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress and Modern Social Theory, Cambridge, 2003

- Joanne Finkelstein, The Fashioned Self, Cambridge, 1991

- Hayden Herrera, ‘Why Frida Kahlo Speaks to the 90’s’, New York Times, October 28, 1990

- Richard Sennett, The Fall of Public Man, Cambridge, 1977

- Rosemarie Garland Thompson, ‘Feminist Theory, the Body, and the Disabled Figure’ in Lennard J. Davis (ed.), Disability Studies Reader, New York, 1997

- Marta Turok, ‘Los Ajuares de Frida: Eclecticismos y Etnicidad’ in Denise and Magdalena Rosenzweig (eds.), El Ropero de Frida, Mexico City, 2007