Creating and Curating with a Conscience

By Timothy Anglin Burgard

August 19, 2021

—Thornton DialArt is like a bright star up ahead in the darkness of the world. It can lead people through the darkness and help them from being afraid of the darkness. Art is a guide for every person who is looking for something.

Most curators consider their chosen profession to be a calling, but a calling to what purpose? Historically, the original role of curators was to preserve, protect, and study the physical objects in their care. Yet, in recent decades, many art museums and curators also have been perceived to be implicitly or explicitly promoting—or defending—the values that these objects represent.

Similarly, as art museums have embraced community engagement through their exhibition and education programs, the concepts of institutional authority, objective standards, and neutral perspectives have been challenged. These outdated ideas have been replaced with a recognition that nearly every choice that a museum or a curator makes is subjective, if not political, and open to interpretation, if not critique.

As a verb, curate derives from the Latin word curare, or, “to take care of,” which clearly relates to care of objects. However, as a noun, curate derives from the Latin word curatus, or “one responsible for the care (of souls),” thus describing those responsible for the spiritual well-being of the people they care for. This dual definition should remind curators that the spiritual nourishment of the museum’s visitors is as important as the physical care of the museum’s objects.

As museums have evolved, some curators have embraced this dual definition, expanding their traditional roles as mediators between artworks and their viewers to encompass new identities as proactive advocates, not only for artists and their artworks, but also for historically marginalized people and ideas. Following the examples set by pioneering artists, scholars, and curators of color, more museum professionals are now curating with a conscience, making changes that typically are incremental, rather than sweeping, but that are nonetheless meaningful and empowering for our diverse audiences.

At the Fine Arts Museums, these issues crystallized around the 2017 exhibition Revelations: Art from the African American South, which celebrated the Museums’ historic acquisition of sixty-three extraordinary art objects by twenty-two self-taught Black artists born in the South. Embodying the promise and progress of freedom in the modern civil-rights era, their innovative explorations of such art forms as paintings, root sculptures, found-object assemblages, quilts, and drawings produced some of the most original and profound works in the history of American art.

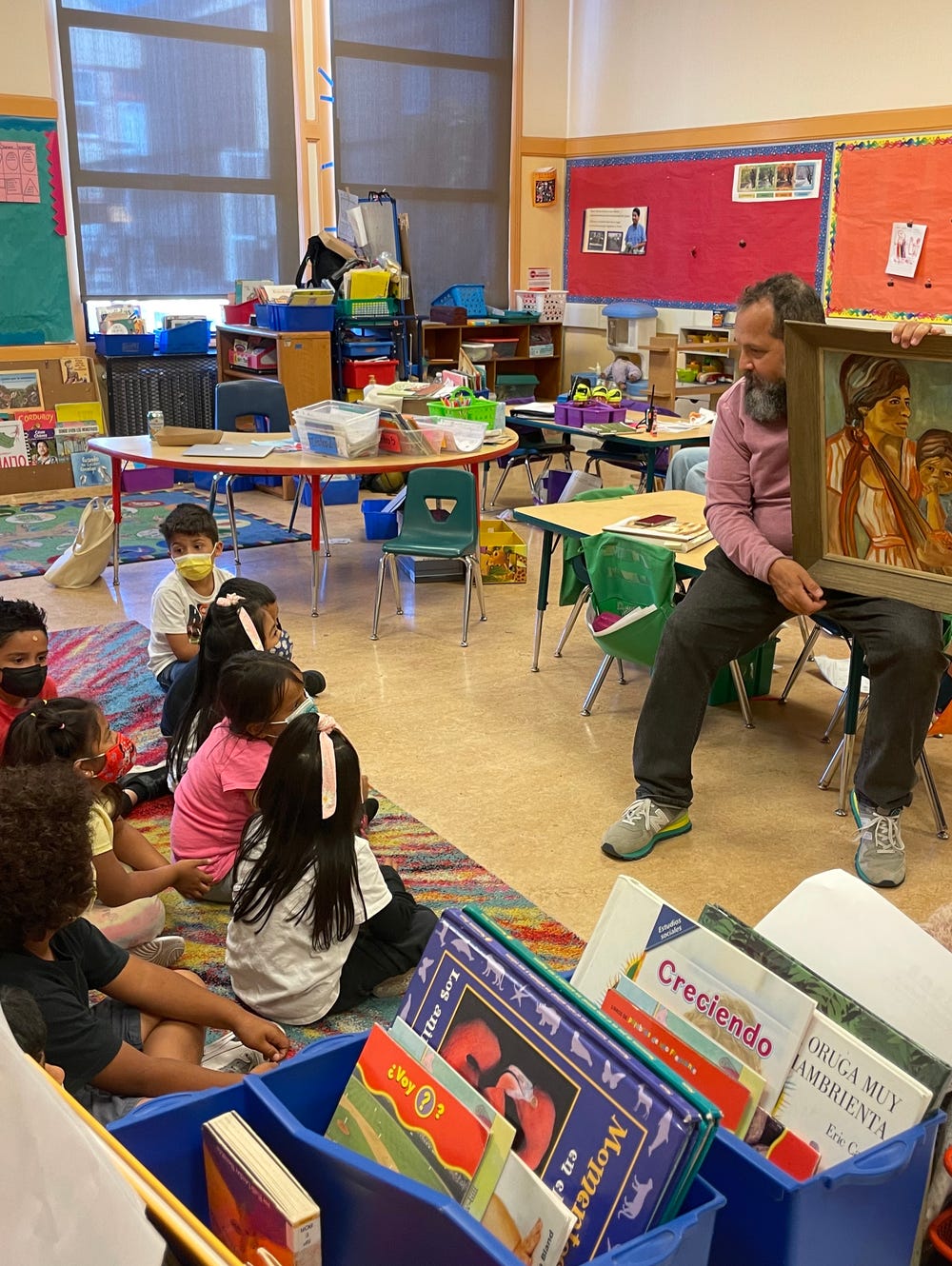

Visitors to Revelations: Art from the African American South in 2017. Photo by Drew Altizer Photography

And yet, historically, these artists and their artworks were marginalized with reductive terms such as “folk” or “outsider” that carry explicit and implicit value judgments. These terms rightly have been challenged, as all art is made by “folk,” or people, and “outsider” is a relative concept dependent upon ever-changing definitions of taste—not to mention one’s relationship to centers of cultural power such as museums. While planning the Revelations exhibition and acquisition, the Fine Arts Museums consistently accorded these creators agency by simply referring to them as “artists.”

Given the correlation between our Museums’ allocation of acquisition funds and its institutional priorities, it is significant that the Fine Arts Museums devoted substantial funds for the Revelations acquisitions—a commitment in turn acknowledged by the partial gift of these works by the Souls Grown Deep Foundation. Indeed, this transformational purchase quadrupled the number of paintings and sculptures by African American artists in the permanent collection—a fact that is simultaneously cause both for criticism and for celebration.

These acquisitions, along with other recent additions to our permanent collection by historically underrepresented artists, have transformed the Museums’ very definition of art. They have also enabled the American Art department curators, while planning the reinstallation of our modern art galleries, to introduce important new perspectives into the histories that are represented.

Lonnie Holly, Him and Her Hold the Root, 1994. Rocking chairs, pillow, root, 45 1/2 x 73 x 30 1/2 in. (115.6 x 185.4 x 77.5 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, American Art Trust Fund, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2017.1.27. © 2021 Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

For example, one of the Revelations acquisitions included in the reinstallation, Lonnie Holley’s Him and Her Hold the Root (1994), comprising two decrepit rocking chairs, a large dead tree root, and a torn and stained pillow, is perhaps the most visually challenging work ever to enter the Fine Arts Museums’ permanent collection. Some viewers, accustomed to more conventional American sculptures, may have trouble even recognizing this assemblage as art. However, like other significant works of art, Holley’s sculpture carries both specific and universal meanings and messages.

Specifically, Holley’s two rocking chairs evoke their former human occupants: the smaller chair, missing its right rocker, rests its arm on that of the larger chair. Together, they support a tree root, an organic object that carries powerful associations with Africans and African Americans violently uprooted from their homelands, families, communities, and ancestors by the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the slavery system, and their racist legacy. However, this tree root also signals connection, evoking family trees and genealogies, as well as multiple generations remembering and claiming their roots.

Joe Minter, The Hanging Tree, 1996. Welded found steel, 83 1/2 x 49 1/2 x 49 1/2 in. (212.1 x 125.7 x 125.7 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, American Art Trust Fund, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2017.1.41. © 2021 Joe Minter / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A second Revelations acquisition, Joe Minter’s The Hanging Tree (1996), installed adjacent to Lonnie Holley’s Him and Her Hold the Root, offers a radically different interpretation of the tree symbol. In place of Holley’s empowering roots, Minter references the trees that white Americans used to hang, torture, and kill African Americans throughout the United States—particularly in the South—in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Between 1877 and 1950, white Americans lynched at least 326 African American men, women, and children in Minter’s native Alabama. The 1981 Ku Klux Klan lynching of Michael McDonald, the last recorded in the United States, also took place in Alabama.

In Minter’s sculpture, abstract steel rods evoke human bodies suspended from a treelike base. The chains evoke the subjugation of slavery and racism—while pointedly noting that often death was the only available means of escaping such oppressive circumstances. The subject resonates with that of “Strange Fruit,” a poem by Abel Meetopol about lynching recorded as a song by the singer Billie Holiday in 1939. Painting a horrific and haunting scene, the lyrics describe: “Southern trees bear strange fruit / Blood on the leaves and blood on the root / Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze / Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.”

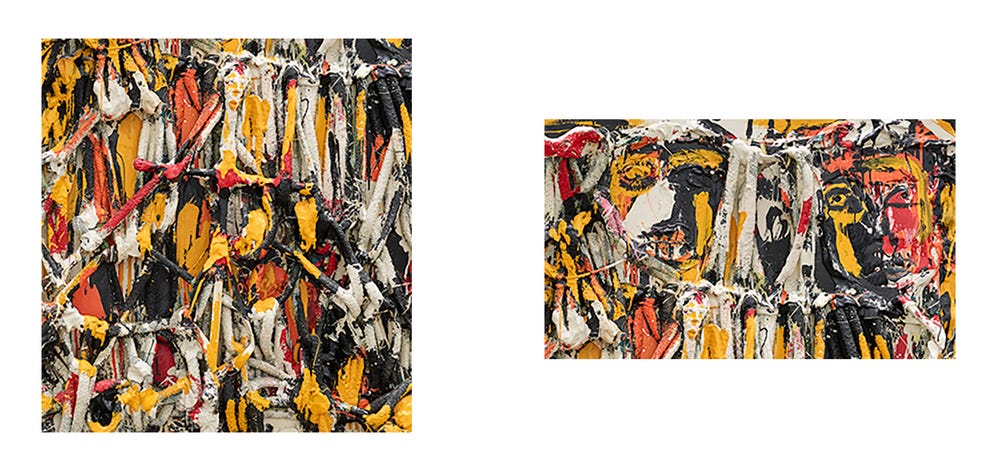

Thornton Dial, Blood and Meat: Survival for the World, 1992. Rope, carpet, copper wire, metal, canvas scraps, enamel, and Splash Zone Compound on canvas on wood, 65 x 95 x 11 in. (165.1 x 241.3 x 27.9 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, American Art Trust Fund, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2017.1.7. © 2021 Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Another Revelations acquisition, Thornton Dial’s Blood and Meat: Survival for the World (1992), is perhaps the artist’s most powerful statement regarding the modern struggle for civil rights. It is installed in a gallery with works by artists who, unlike Dial, never personally experienced racist police brutality, or had to consider whether they might be punished for calling out and criticizing racism in the United States.

Dial’s assemblage painting, fabricated from carpet rope, metal, and a tire iron, provides a radically different insider’s perspective from Jack Levine’s oil painting of civil rights protestors in Dial’s home city of Birmingham, Alabama. Inspired by television news footage and print-media photographs of police dogs attacking peaceful protestors, Levine intended Birmingham ’63 (1963) to inspire both empathy and outrage in viewers, but it represents an outsider’s view of the Black protagonists, who embody heroism and stoicism in the face of threatened violence.

Jack Levine, Birmingham ’63, 1963. Oil on canvas, 71 x 75 in. (180.3 x 190.5 cm); 78 x 82 in. (198.1 x 208.3 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Dr. Leland A. Barber and Gladys K. Barber Fund, American Art Trust Fund and Mildred Anna Williams Collection, by exchange, 1999.69. Art © Susanna Levine Fisher/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

In contrast, Dial’s visceral visual vocabulary provides an insider’s view of the decades of violence perpetrated upon those who struggled for justice during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Barely discernible in his tangle of blood-stained rope, evocative of human bondage, is a crucifix, along with painted heads of the murdered martyrs Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., President John F. Kennedy, and Senator Robert F. Kennedy. Dial’s subtitle, “Survival for the World” suggests that an enormous human sacrifice has been made, not just for Black freedom and equality, but also for the global survival of humanity itself.

Details of crucifix and heads from Blood and Meat: Survival for the World

Dial’s central portrait, displayed like a religious image of Jesus on the Veil of Veronica, is likely that of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till, who was kidnapped, tortured, and killed by racists in Money, Mississippi, in 1955. A published photo of Till’s battered face visible in an open coffin at his Chicago funeral shocked the nation. Dial’s moving memorial records that the struggle for civil rights claimed the lives of larger-than-life leaders such as Dr. King, and of ordinary human beings like Till—both of whom were martyred and left extraordinary legacies.

Detail of Emmett Till portrait from Blood and Meat: Survival for the World

Through his art, Dial himself became an activist for civil and human rights, linking the past to the present, and thus revealing the continuing relevance of these issues. The inclusion of this major work in the Museums’ permanent collection of American art brings a new vision and voice to public discussions surrounding the ongoing struggle against systemic racism. Dial’s still-timely message serves as a reminder that real and lasting change only occurs when people with a conscience work both individually and collectively towards a common goal.

—Thornton DialPeople in the United States do not hate one another. But they be scared of one another. The way life have been taught is to make black peoples and white peoples be against each other in fear. I don’t believe there is any natural hate in people. I believe there is natural love.

Further reading: Timothy Anglin Burgard, Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley, Joe Minter, and Lauren Palmor, Revelations: Art from the African American South, Munich, London, New York, Delmonico Books / Prestel, 2017.

The following artists were represented in the exhibition Revelations: Art from the African American South (2017) and are in the permanent collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco: Jesse Aaron, Willie “Ma Willie” Abrams, Mary Lee Bendolph, David Butler, Archie Byron, Thornton Dial, Thornton Dial Jr., Ralph Griffin, Bessie Harvey, Lonnie Holley, Joe Light, Ronald Lockett, Joe Minter, Jessie T. Pettway, Plummer T. Pettway, Florine Smith, Mary T. Smith, Mose Tolliver, Geraldine Westbrook, Annie Mae Young, Deborah Pettway Young, and Purvis Young.

Text by Timothy Anglin Burgard, Distinguished Senior Curator and Curator in Charge of American Art, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Learn more about the American art collection.