I was an art history major as an undergraduate attending college at the height of the Vietnam War. Protests were a daily occurrence on campus and the anti-establishment tenor of the day forced me to confront an uncomfortable reality: In politically engaged student circles, the study of art history—specifically Western painting—hardly seemed important. And a career as an academic, curator, or gallerist in the rarefied circles of the art world was considered elitist by many of my fellow undergrads. Did art history have any relevance in a nation torn apart by the political divide the war had generated?

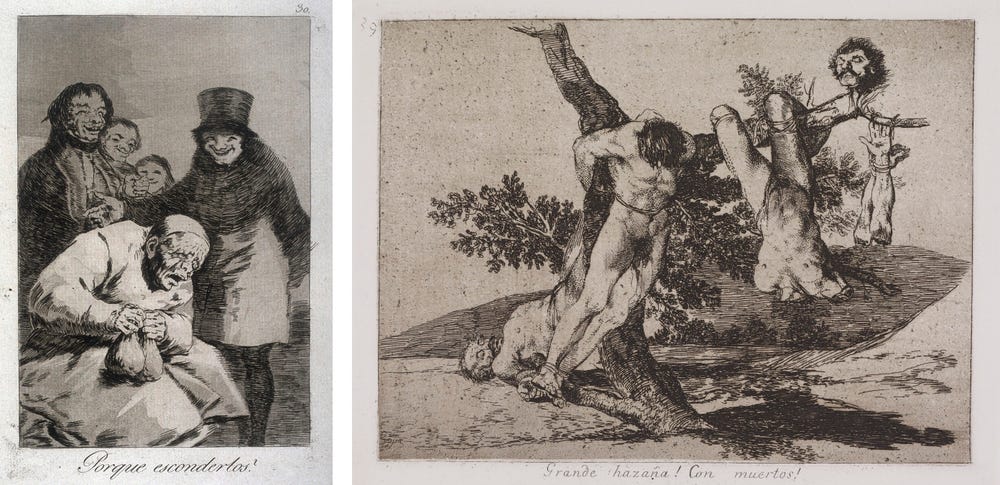

(L) Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, Porque esconderlos! (Why Hide Them?), plate 30 from the series “Los Caprichos (Caprices),” 1799. Etching, burnished aquatint, and drypoint, 21.5 x 15 cm (plate). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mrs. Philip N. Lilienthal, Jr., 1971.36.30. (R) Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, Grande Hazaña! Con Muertos! (An Heroic Feat! With Dead Men!), plate 39 from the series “Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War),” ca. 1810–1820. Etching, aquatint, and drypoint, 15.5 x 20.5 cm. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, 1963.30.1028.

My “Aha!” moment came one day in a lecture class devoted to the art of Francisco Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828). Slides of Goya’s prints appeared on the screen, including etchings from two of his most famous series, Los caprichos (The Caprices) (1797-1798) and the Los desastres de la guerra (The Disasters of War) (1810-1820). I was dumbfounded—never before had prints been featured in my art history classes, and never before had I seen such a damning artistic treatment of war and the ruling elite. After the lecture, the professor invited students to visit a display of Goya’s prints installed in the auditorium hallways. I learned that these were etchings, issued in multiple editions with impressions that were accessible and affordable then, as now, to everyone, not just the wealthy.

Determined to better understand the history of prints, this egalitarian art form that had existed for centuries, I attended graduate school with a focus on print studies and worked to develop expertise in the field of graphic arts. (You can imagine my delight when, as a new curator at the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, one of my first duties was to catalogue and label several portfolios of Goya’s prints!)

Since then, I’ve enjoyed the work of contemporary artists who have, at one point or another, been engaged with political themes in their prints, and I am pleased to say that many have been acquired by the Achenbach in recent years. (Enrique Chagoya’s series The Return to Goya’s Caprichos [1999] is a favorite.) So, it was with great delight that I found the etching Mendacia Ridicula (The Wheel of Ixion), by David Avery, in The de Young Open, and was able to acquire it for the Achenbach collection. Avery’s piece was one of ten works on paper that was purchased from the show, an incredible opportunity that was also enthusiastically supported by my curatorial colleagues Tim Burgard and Jill D’Alessandro, who also selected works to add to the collections.

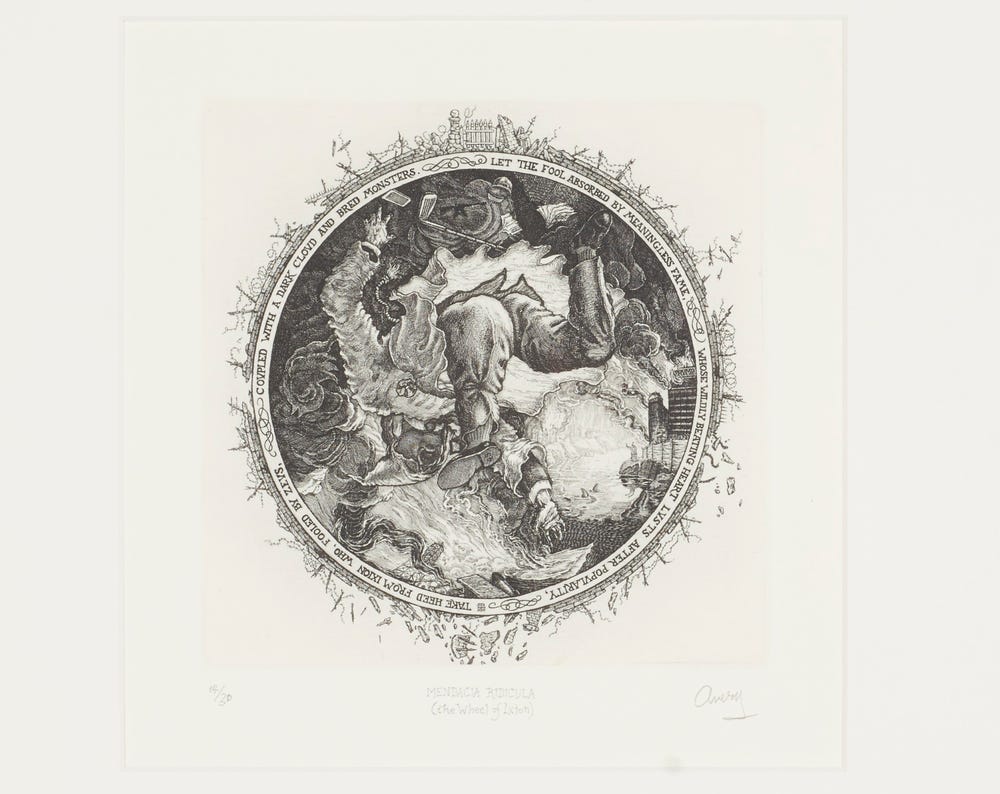

David Avery, Mendacia Ridicula (The Wheel of Ixion), 2018. Etching, 15.2 x 15.2 cm (plate). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, gift of the Achenbach Graphic Arts Council, 2020.52

The title and subtitle of the print (above) required some quick research to discover that “Mendacia Ridicula” is a Latin phrase that can be translated as “ridiculous lying.” The “Wheel of Ixion” refers to the mythical Greek king named Ixion who tried to seduce Zeus’s wife, Hera, and was punished for his temerity by being bound to a fiery wheel that spun around for eternity.

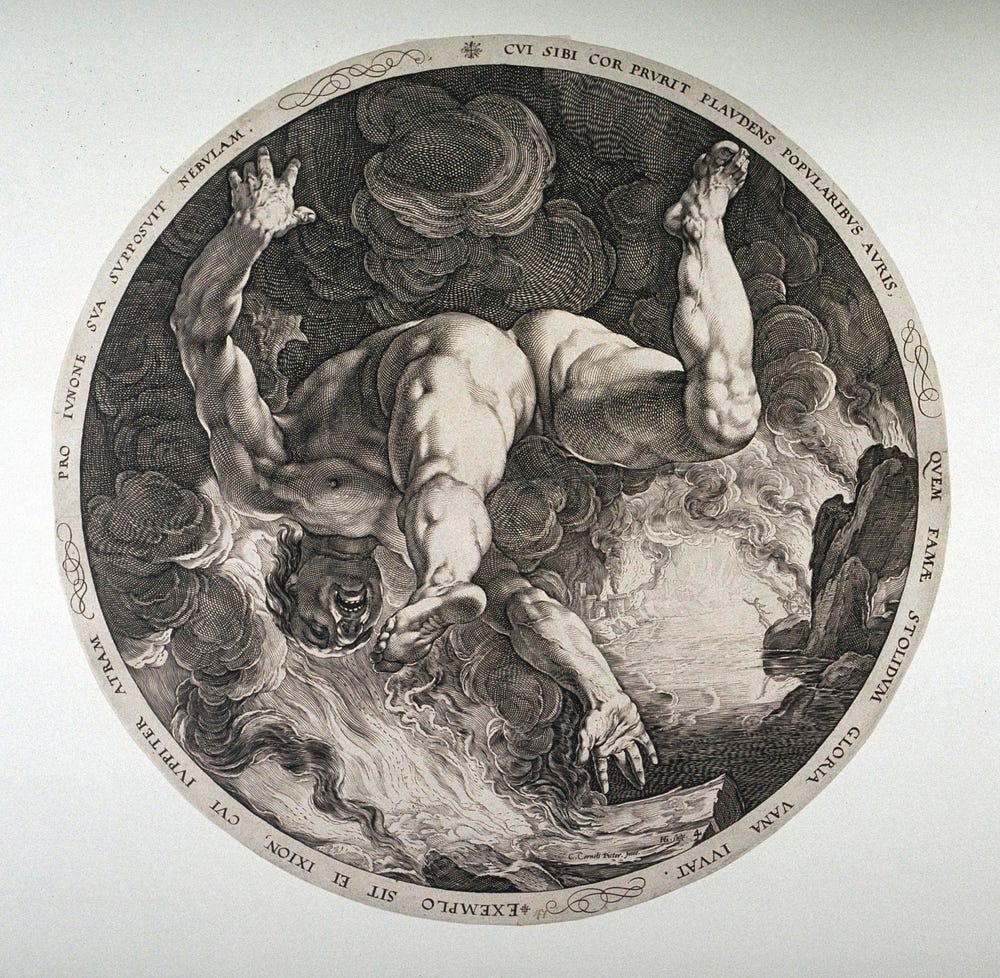

Aficionados of old master prints will recognize that Avery’s composition in the round refers directly to the tondo (circular) prints of Dutch printmaker Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617). Goltzius created a series of engravings in 1588, all of them showing muscular male nudes falling from the sky, modeled after paintings by Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem (Dutch, 1562-1638). Each print depicts a different character from mythology who, because of arrogant behavior, was punished by the gods with a form of eternal torture. A Latin inscription engraved around each of the compositions describes the crime and punishment. (It is thought that Goltzius created the series to criticize the arrogance of Phillip II of Spain, who was trying to subjugate the Netherlands at the time.) The Achenbach has the complete set of four Goltzius prints, titled The Four Disgracers (below), of which Ixion is the most complex.

Hendrick Goltzius after Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem, Ixion from “The Four Disgracers,” 1588. Engraving, 32.3 x 30.8 cm (image). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts Endowment Fund, 1964.142.110

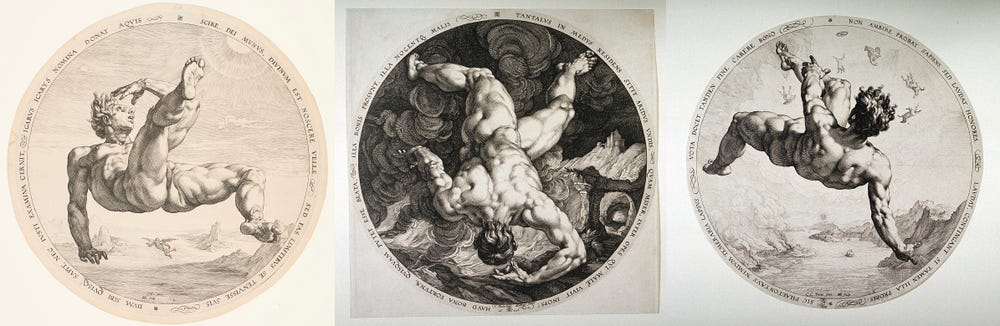

(L) Hendrick Goltzius after Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem, Icarus, from “The Four Disgracers,” 1588. Engraving, 33 x 33 cm (image). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Gift of the Achenbach Graphic Arts Council, 2017.6. (C) Hendrick Goltzius after Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem, Tantalus, from “The Four Disgracers,” 1588. Engraving, 32.9 x 32.8 cm (image). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts Endowment Fund, 1964.142.108. (R) Hendrick Goltzius after Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem, Phaeton, from “The Four Disgracers,” 1588. Engraving, 32 x 31.2 cm (image). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts Endowment Fund

For the text in Mendacia Ridicula (The Wheel of Ixion), Avery (American, b. 1952) provides a rough translation of Goltzius’s Latin description (and adds some clarifying words of his own) to read: “Let the fool absorbed by meaningless fame whose wildly beating heart lusts after popularity, take heed from Ixion who, fooled by Zeus, coupled with a cloud and bred monsters.” Avery’s falling male figure is fully clothed, wearing Ku Klux Klan robes over his business attire. A cell phone and a golf club fly through the air and, as if those weren’t obvious enough clues to the subject of his satire, Avery has added a large “Trump” sign on a high-rise building in the background. Created in 2018, two years into the Trump administration, the print was inspired, Avery suggests, by the behavior of politicians: “As regard to the demand for civility in public discourse by the current dominant political organization enabling insanity, I can only reply, ‘Mendacia Ridicula.’”

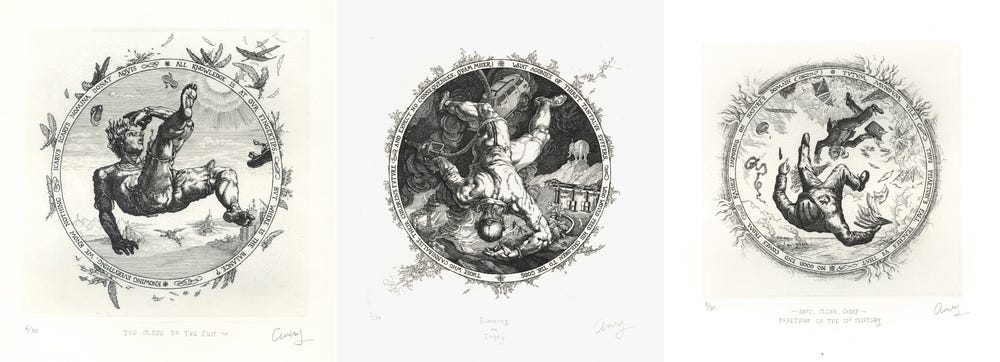

David Avery, Too Close to the Sun, 2013. Etching, 15.2 x 15.2 cm (plate). (C) David Avery, Running on Empty, 2016. Etching, 15.2 x 15.2 cm (plate). (R) David Avery, Safe, Clean, Cheap – Phaeton in the 21st Century, 2011. Etching, 15.2 x 15.2 cm (plate). All courtesy of the artist.

Safe, Clean, Cheap: Phaeton in the 21st Century (above right, 2011), an image that visualizes the destruction of the environment and its vestiges, was Avery’s first print in homage to Goltzius, and admittedly not done with the intention of creating a series of four. Nevertheless, Too Close to the Sun (above left), with its reference to the punishment of Icarus, was editioned in 2013 as Avery’s commentary on the American preoccupation with cell-phone technology. In 2016, Running on Empty (above center) appeared, a critique of America’s dependence on big oil that borrows its composition from Goltzius’s tondo featuring the fall of Tantalus. With the completion of the fourth tondo, Mendacia Ridicula, in 2018, Avery provided a clue on his website’s blog as to his rationale for producing a complete series in homage to Goltzius:

—David AveryWhen I created my etching based on Goltzius’s Phaeton in 2011, little did I realize that I would continue this theme over the years and appropriate, one by one, and for my own nefarious purpose, each of [Goltzius’s] prints.

Viewers of these works in 2021 may not find Avery’s creative motivations as wicked or perverse at all, but they will no doubt find them, as I did, clever visual musings (and warnings) of our human follies and failures, following in the tradition of Goltzius, Goya, and those artists who have, in their graphic work, exposed evil and injustice since the sixteenth century.

Text by Karin Breuer, Curator in Charge, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts.

Unfortunately, the de Young had to close its doors to the public again only six weeks into the run of The de Young Open. Learn more about how our staff organized the exhibition, and explore some of the artworks acquired from it. We are thrilled to announce our intentions of making The de Young Open a triennial event.