In early February, the Fine Arts Museums announced the acquisition from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation in Atlanta of 62 works by African-American artists from the Southern United States. These works address some of the most profound and persistent issues in American society, including race, class, gender, and religion.

An exhibition featuring all of the works from the acquisition, Revelations: Art from the African American South, will open on June 3, 2017, at the de Young. Below are three featured works from the show, accompanied by quotes from the artists themselves.

Thornton Dial (1928—2016)

Dial—whose life encompassed the institutionalized racism of Jim Crow, the modern civil rights movement, and the first African American president—is the most acclaimed artist represented in the collection. Dial began making art after losing his job as a steelworker in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1981. His ambitious artworks address a panoramic array of issues spanning from African American experience in the South to the events of 9/11 and America’s war in Iraq.

—Thornton DialArt is like a bright star up ahead in the darkness of the world. It can lead peoples through the darkness and help them from being afraid of the darkness. Art is a guide for every person who is looking for something.

Dial’s sculpture Lost Cows (2000-1), created with painted skeletons of cows, ostensibly addresses the cycles of life and death that are critical to rural agrarian life. The abstracted skeleton behind the four white cows struggles to guide his wayward herd. As the title Lost Cows suggests, the sculpture critiques the supposedly superior white supremacists (represented by pelvic bones that resemble Ku Klux Klan masks) that created the Jim Crow system, while simultaneously becoming dependent upon—and “lost” without—African American nannies, servants, maids, cooks, drivers, and caddies (represented by a white golf bag).

Thornton Dial (1928-2016), Lost Cows¸ 2000-2001. Cow skeletons, steel, golf bag, golf ball, mirrors, enamel, and Splash Zone compound. 76.5 x 91 x 52 in. Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio, Rockford, IL / Art Resource, NY © Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

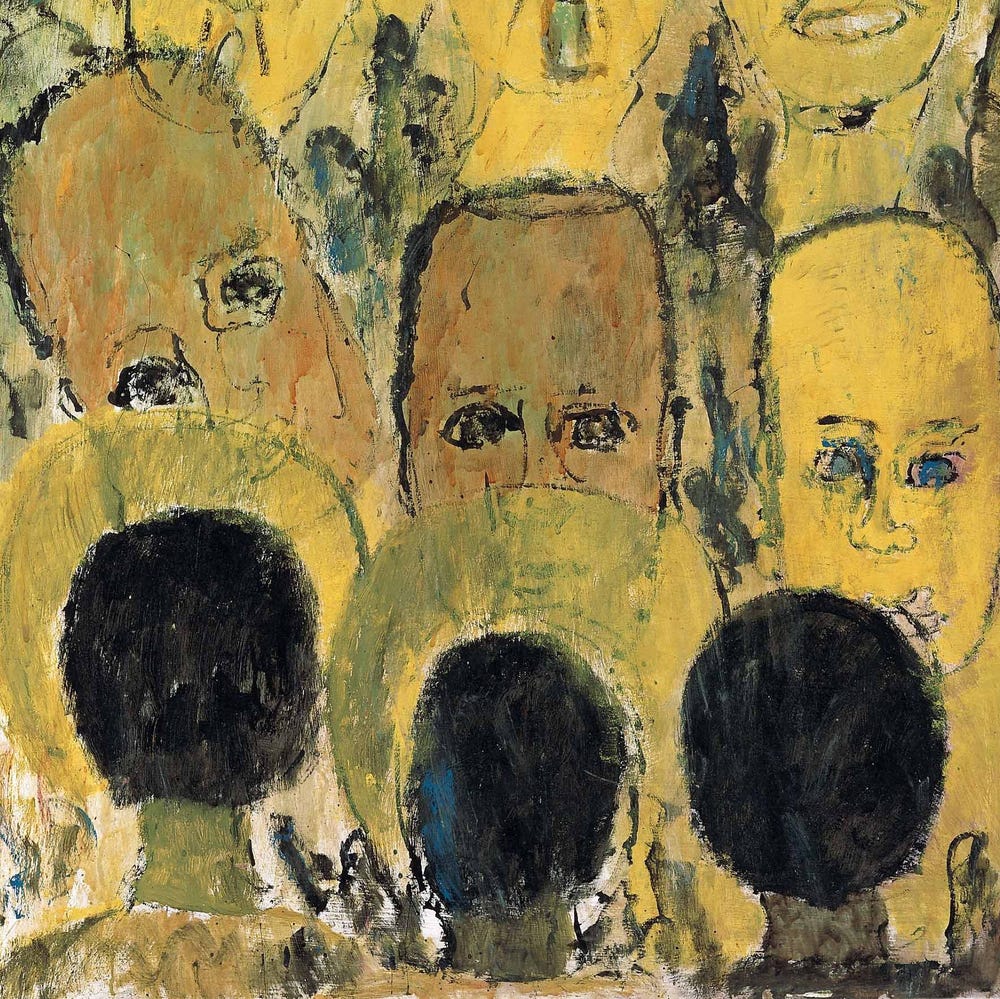

Lonnie Holley (b. 1950)

The 1979 death of Holley’s niece and nephew in a house fire led him to carve their tombstones, which marked the beginning of his career as an artist in Birmingham, Alabama. Holley combines the most pedestrian of recycled materials to create visual stories—often linking the past to the present—that are intended to teach and to inspire.

—Lonnie HolleyMy thing as an artist, I am not doing anything but still ringing that Liberty Bell, ding, ding, ding, on the shorelines of independence. Isn’t that beautiful? Can you hear the bell I’m ringing? And will you come running?

Holley’s assemblage Him and Her Hold the Root (1994), the artist’s most iconic and striking work, is comprised of a smaller “female” rocking chair that rests its “arm” upon a larger “male” chair, as if mirroring the supportive and stabilizing relationship of an absent female/male couple. Together, they support a large, anthropomorphic tree root with a “trunk” and “limbs” that recalls both family tree genealogies and the preservation of oral history and traditions through the generations. The composition clearly evokes elders remembering their roots, but more subtly suggests that a younger generation may forget—or ignore—its past.

Lonnie Holley, Him and Her Hold the Root, 1994. Rocking chairs, pillow, root, 45 1/2 x 73 x 30 1/2 in. (115.6 x 185.4 x 77.5 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, American Art Trust Fund, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2017.1.27. © 2019 Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ronald Lockett (1965–1998)

Lockett, the nephew of Thornton Dial, lived in Bessemer, Alabama, and inherited from his uncle and mentor a belief in the political and social power of art. His works, many fabricated from sheet-metal siding, focus on both timeless themes of life, death, and rebirth, as well as contemporary political and social issues, including nuclear destruction, domestic terrorism, civil rights, and the degradation of the environment. Lockett’s works—all created in the decade before his death at 32 from complications of HIV/AIDS—were recently featured in a major retrospective exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum (2016).

—Ronald LockettI don’t think I’ll be here when I’m 60, so I want to prove to people that I can succeed in what my dream was.

Lockett’s sheet-metal assemblage England’s Rose (1997) was inspired by the death of Princess Diana, who was among the first public figures to physically embrace people living with HIV/AIDS. The vertical bars recall both the vertical fence of Kensington Palace that was inundated with floral bouquets and the public’s perception that Diana was “imprisoned” by her role in the royal family. The gradual but inexorable descent of the rose bouquets from vivid life and light at the upper left into death and darkness at the lower right would have had special resonance for Lockett, who died the year after the work was completed.

Ronald Lockett (1965-1998), England’s Rose, 1997. Tin and paint on wood, 48.25 x 48.25 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, museum purchase, American Art Trust Fund, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection. Artwork: © Estate of Ronald Lockett / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio, Rockford, IL / Art Resource, NY