Who’s That Lady? Identifying the Sitter in Our Tudor Portrait

By Elise Effmann Clifford, head of paintings conservation

July 20, 2023

Attributed to Robert Peake (ca. 1551–ca. 1619), Portrait of Frances Walsingham, Lady Sidney (detail), ca. 1586–1590. Oil on wood panel, 33 1/2 x 29 1/8 in. (85 cm x 74 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Mildred Anna Williams Collection, 1954.75

Her penetrating gaze has intrigued me since I first joined the conservation department at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in 2007. Dressed in sumptuous black velvet, bedecked with pearls and elaborate lace, and known simply as a Portrait of a Lady (by an unknown Tudor-era artist), the sitter was clearly a woman of status. Each time I passed by her, I wondered if her identity had truly been lost to time or if there was more that could be discovered about who she was.

Attributed to Robert Peake (ca. 1551–ca. 1619), Portrait of Frances Walsingham, Lady Sidney, ca. 1586–1590. Oil on wood panel, 33 1/2 x 29 1/8 in. (85 cm x 74 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Mildred Anna Williams Collection, 1954.75

The opportunity to learn more about the portrait came in 2018, when it was brought to the paintings conservation department for assessment. Looking at the painting under different lighting conditions and the microscope enhanced my understanding of its condition and level of restoration, as well as the materials and techniques used by the artist. It was clear the portrait would benefit from treatment to remove a very unattractive modern sprayed varnish, as well as old, discolored overpaint.

A detail of the portrait in specular light showing the discolored overpaint running through the lace ruff and the sprayed varnish on the surface in the background.

Each in-depth treatment is a chance to expand what we know about an artwork in our collection. X-radiography and infrared reflectography revealed changes the artist made to the position of the hand, as well as the ink lines the artist used to sketch the forms before painting.

Infrared reflectography mosaic detail of the hand, showing the artist’s initial drawing.

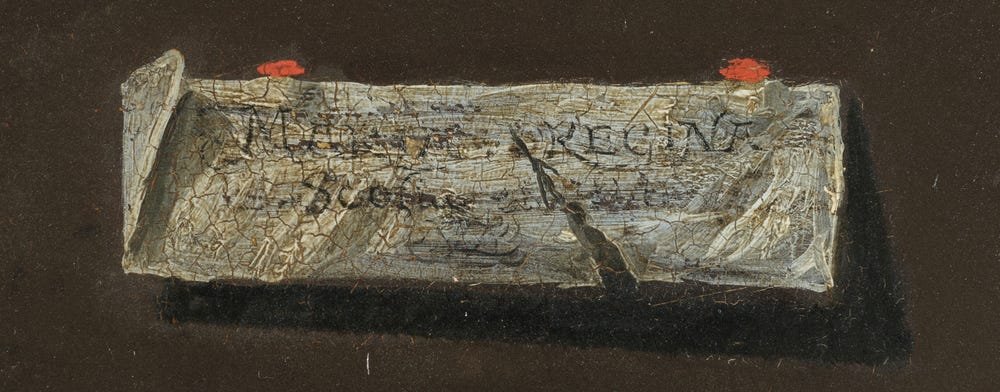

I was curious about the small trompe l’oeil label, or cartellino, visible in the upper-left corner that read “MARIA REGINA SCOTIAE” or “Mary, Queen of Scots.” It was clear that this false inscription was added later, as the lettering went over layers of varnish and across cracks in the paint.

The cartellino before treatment, with the later inscription.

This cartellino identifies the portrait as having once been in the collection of John, Lord Lumley, an Elizabethan-era courtier. An inventory of his collection begun in 1590 notes each person in his vast portrait collection. David Piper, curator at the National Portrait Gallery in London, proposed in a 1957 essay in the Burlington Magazine that the sitter in our painting was Frances Walsingham, the daughter of Elizabeth I’s principal secretary and spymaster, Francis Walsingham. This was based on the limited number of women of the correct age in the inventory who weren’t yet identified. However, no further attempts had been made to confirm this hypothesis over the intervening years.

While my treatment began in 2018, progress slowed as other projects took priority. But in 2020, we learned we’d be the third venue for The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England, organized with the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Cleveland Art Museum. This gave us the opportunity to present our portrait in the show, and I was again able to focus on the varnish and overpaint removal.

The author removing the varnish in 2021.

I turned my attention to the cartellino as I neared the end of the varnish cleaning. The removal of the “Mary, Queen of Scots” label was crucial to uncovering any evidence of the original inscription that might remain. Under the microscope, I carefully took off the upper layers of varnish and repainting. Although much of the original inscription had been lost in past cleanings, fine cracks had been left behind in the white paint in the precise locations of the original letters. Hope surged through me that at least some of this information could be reclaimed.

Detail of the paint and cracks remaining from the original lettering.

After several attempts to make sense of the lettering under the microscope, I asked Randy Dodson, our head photographer, to take a high-resolution detail of the area. Using Photoshop, I digitally retouched the large cracks and losses in the white parts of the label to reduce the visual noise.

The cartellino with digital retouching of large cracks and losses.

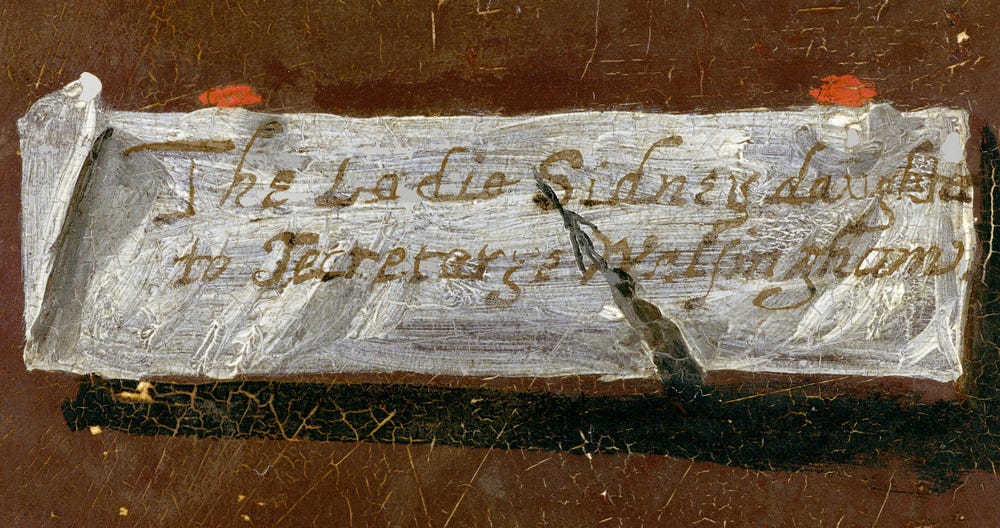

I then zoomed in at very high resolution and digitally retouched the abraded areas between the micro-cracks of the original lettering, revealing the inscription: “The Ladie Sidney daughter to Secretarye Walsingham.”

The cartellino with the recreated inscription.

One of the things I treasure most about my role as a museum conservator is the opportunity to deepen our understanding of an object’s place in history. With little written evidence about her life, Frances Walsingham is largely known through her connections to powerful men of the Elizabethan court. The daughter of the queen’s spymaster, Walsingham married Philip Sidney, the renowned poet and soldier, in 1583 when she was 15. Widowed three years later, she went on to marry Robert Devereux, the second Earl of Essex, in 1590. This marriage also ended with her husband’s death, this time by beheading for rebelling against the queen in 1601.

Our portrait captures Frances Walsingham independent of these male relationships, giving a strong sense of her as her own person. It has been a highlight of my career to return her name and story to our beautiful Tudor portrait.

For more about this discovery, an extended essay is available in the Burlington Magazine, June 2023, No. 1443, Vol 165, pp. 622-26.