Sara Zapata, If I Could, 2017. Natural and synthetic fiber, handwoven cloth, rope, cement, steel. Collection of the artist, Courtesy of Deli Gallery

Since the 19th century, carpets have become a site of mass production and exploitation of feminized work. However, carpet-inspired art, along with other forms of textile and fiber art, has contributed to the development of eco-aesthetics, or geo-aesthetics, which is interrupting capitalism’s predetermined outcomes: mass production, consumerism, commodification, and labor exploitation. Carpet art practices are crucial for thinking about eco-art and ecological values; it exposes profound relations between weavers, environments, and communities.

Carpet weaving is a site of work, art, craft, reflection, storytelling, remembering, and community-making. It relies on the appreciation of the ordinary. As noted by textile artist Terra Fuller, who learned to weave from carpet makers in Morocco, “This functional art is generally the only furniture that helps families to survive. Newlyweds sleep on the carpets; babies are conceived and are born on the carpets, and the elderly pass away on the carpets. In other words, the entire cycle of life from conception to death occurs on these carpets.”

The story of carpets, carpet looms, and carpet-inspired art is usually left out of the histories of labor, art, and technology. The first computer was a carpet loom, and much of computer terminology is borrowed from weaving (e.g., texture, pattern, layering, links, nodes, sampling, net, networks, narratives, web, threads). As artist Victoria Manganiello notes, the loom relies heavily on tension, math, and order. Yet, the result of weaving is an organic and soft material, something every human interacts with every single day. She explains, “I'm drawn to that juxtaposition of order and flexibility.”

Many women-produced works continue to live in the shadow of the informal economy and the private sphere. The mass production of carpets, and its control by middlemen, has concealed women’s labor, framing it as an extension of their bodies. Women weavers are seen as victims of economic exploitation rather than agents of work, art, and craft. The separation between arts, crafts, and commodities has obscured the artistic aspects of carpet weaving.

Alexandra Kehayoglou, No Longer Creek, 2016. Textile tapestry (handtuft system), wool, 820 cm x 460 cm. Presented at Design Miami/ Basel, 2016 | Basel, Switzerland. Commissioned by Artsy. Courtesy of Artsy and The National Gallery of Victoria

What some authors call ecocide, or extensive destruction, damage to, or loss of ecosystem(s), is part and parcel of our current reality. But in eco-aesthetics, the imagining of a world to come is artistically inspiring and politically refreshing. “Eco-art” is the convergence of art and some of the market’s most feminized and exploited segments, exposing profound relations between artists, environments, and communities. The economic, social, spiritual, ritual, and cultural dimensions come together to produce a much more complex understanding of values. The link between eco-aesthetics and ethics provides the possibility of alternative practices and resistance to individualism.

In carpet-inspired artwork, artists break through the disciplinary order of commodity culture, turning carpets into life-affirming objects. Carpet artists’ engagement with eco-aesthetics creates space for a future that interrupts commodified labor, one where labor is genuinely free and autonomous. The making of carpets, a performative art, emphasizes participation and collaboration. It challenges the effects of consumer-based design by pushing viewers to think of the possibilities of a world yet to come.

Alexandra Kehayoglou

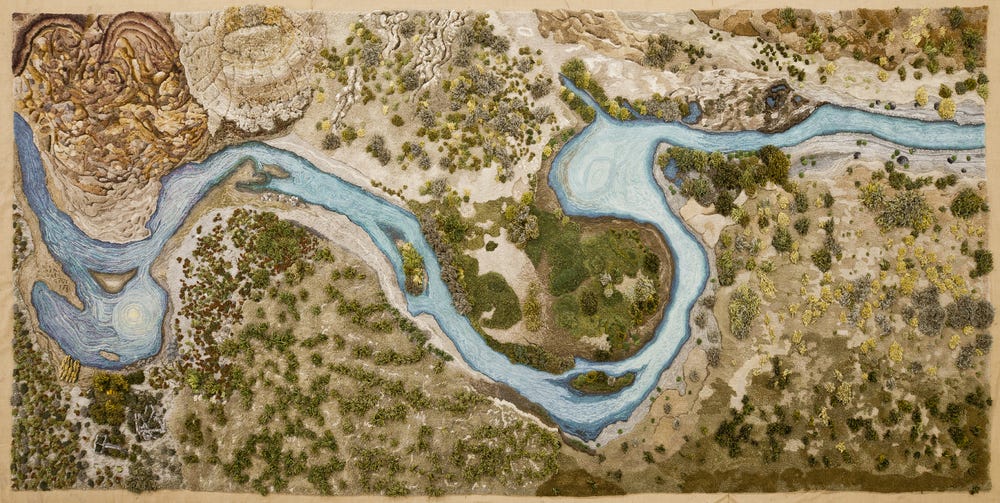

Alexandra Kehayoglou, Santa Cruz River, 2016–2017. Textile tapestry (handtuft system), wool. 980 cm x 420 cm. Presented at National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) Triennial | Melbourne, Australia 2018. Commissioned and acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Courtesy of The National Gallery of Victoria

Alexandra Kehayoglou is an Argentinian-Greek carpet and textile artist who reflects on our collective memory of the landscape and preservation of nature. Her work explores the environment, deforestation, and wilderness extinction. She refers to her carpets as a site of activism where she documents possibilities for new ecological futures.

Alexandra Kehayoglou, designboom, 2021I believe that art can be a mirror, and I try with my work to reflect our humanity in relation with the landscape.

Kehayoglou’s work includes memories of various landscapes the artist has visited and desires to preserve, as well as landscapes that have disappeared due to environmental destruction. She makes perceptible what is imperceptible or forgotten, including the dead streams, clogged arteries, and sheer devastation of the natural world. Her grasslands and field tapestries depict sublime realities for viewers’ contemplation and interaction. She calls for the imagining of a future that could be different. In her view, “Textiles carry information. Threads are like veins, or bridges or cables, they carry this faculty inherently. . . . The landscapes I choose to reproduce are not random. There is always an intention when we tuft. We put this intention into the making; it’s like a mantra or a prayer.”

Victoria Manganiello

Victoria Manganiello, Get me Out of Here, 2012. Natural and synthetic fibers and dyes. Tang Museum, Saratoga Springs, NY

Manganiello, a New York City-based weaver and designer, creates geological, political, and infographic maps in sculptural, 3D installations big enough to step through. Using thread, she connects points on different city or world maps. She explains, “It gives viewers a chance to experience what it’s like to be between two places: literally ‘on the map,’ and in the physical space they’re occupying.”

Sarah Zapata

Sarah Zapata, A little domestic waste IV, 2017, Natural and synthetic fiber, hand-woven fabric, steel, cement, coiled rope. Collection of the artist, Courtesy of Deli Gallery

Sara Zapata refuses to separate the object of pleasure from the backbreaking labor behind it. Her work has never been more relevant. The Peruvian American weaver creates artwork that opens up space for a future in which woven work is celebrated, compensated, and revered in all its sensory, psychedelic glory. In her view, while carpets are seen as a symbol of tradition, they are rather indicative of how tradition survives and changes through colonization.

Carpet weaving involves maintaining roots and traditions rather than uprooting them. Carpet artists see weaving practices, not as frozen in time and space, but as changing, renewing, and transforming. Weaving is a multilayered, collaborative art. The imperfect knots on the back of a carpet tell the story of weaving as the convergence of body and loom, design and improvisation, actual and virtual, art and commodity. It is a reminder of the aesthetics of everyday life, where the dreadful destruction of our ecosystem intersects with the layers of knots, threads, and colors that make up trees, flowers, and landscapes.

Text by Minoo Moallem, professor of gender and women’s studies and the director of media studies at UC Berkeley. She is the author of numerous publications, including Persian Carpets: The Nation as a Transnational Commodity.

Learn more at Persian Carpets and Women’s Creative Work.