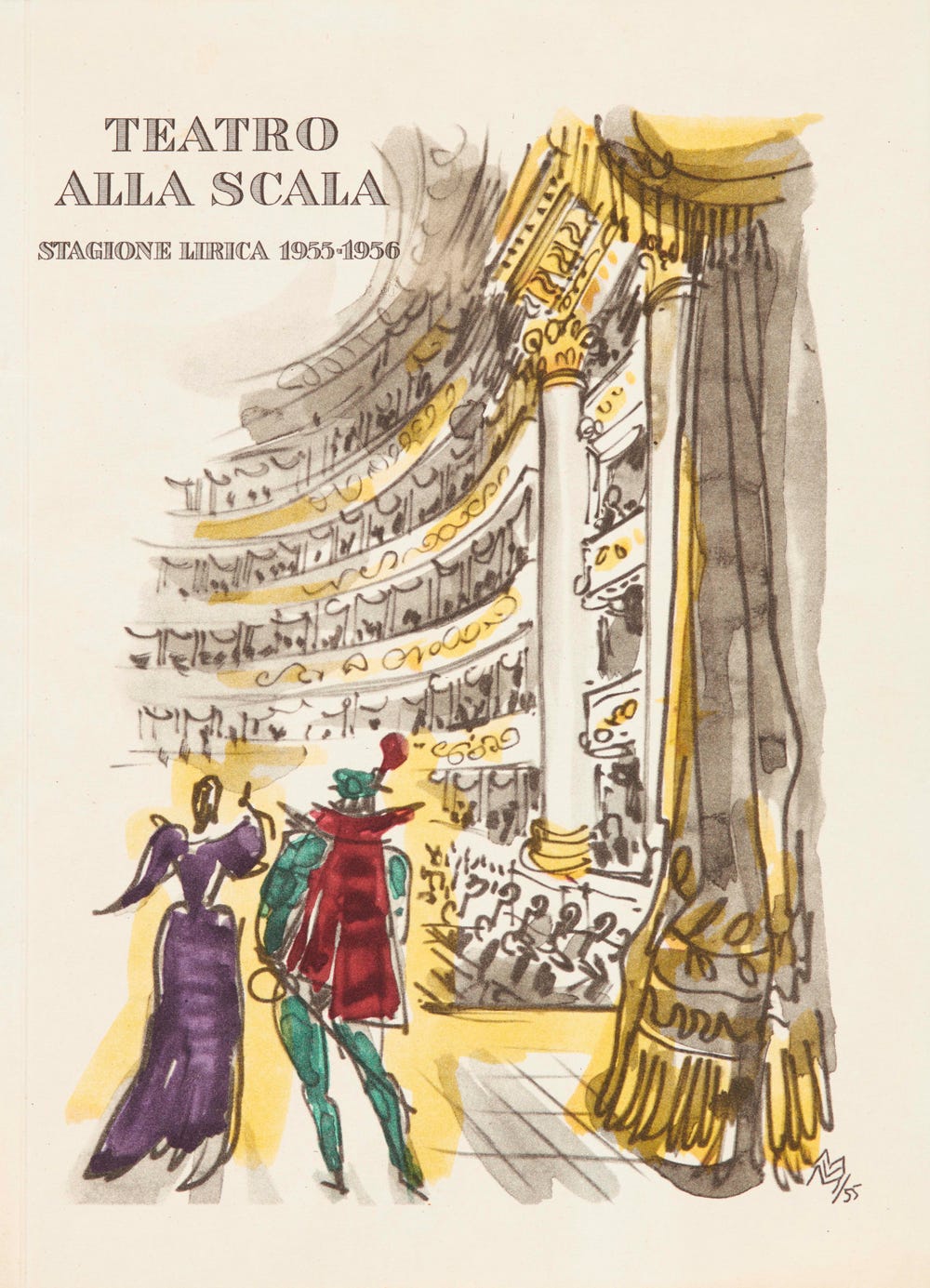

André Beaurepaire (1927–2012), Set design for the ballet Cenerentola, Act II, Teatro alla Scala, Milan, 1955–56. Watercolor on paper, 19 x 25 in. (48.3 x 63.5 cm) (sheet). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Theater and Dance Collection, gift of Alma de Bretteville Spreckels, T&D1959.30 © 2007 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

As intermission ends and a crowd returns to their seats in Milan’s Teatro alla Scala, 19-year-old Carla Fracci waits in the wings. It is December 31, 1955, and principal dancer Violette Verdy has been called away to Paris, prompting Fracci’s unexpected debut in the title role of Alfred Rodrigues’s newly choreographed La Cenerentola (Cinderella). Changed out of her tattered rags from the ballet’s opening, Fracci wears a diaphanous cape draped over a resplendent white tutu and jeweled tiara. As the curtain draws to reveal a grand ballroom, finely dressed courtiers from across the land enter while spritely jesters frolic among them. Soon the stage is alive with energetic footwork and fluttering tulle skirts as the elegant gentlemen guide their partners about the room to Prokofiev’s exuberant, often playful, score. Finally, as the music peaks and then falls to a mysterious whisper, Fracci takes center stage. Hovering en pointe with her arms floating in demi-seconde, everyone — the audience members, her notorious stepsisters, and, above all, the prince — is transfixed by her beauty.

Cenerentola, Act I, at Teatro alla Scala, Milan featuring a set design by André Beaurepaire, 1960–1961. Photograph by Erio Piccagliani

Cenerentola, Act II, at Teatro alla Scala, Milan featuring a set design by André Beaurepaire, 1965–1966. Photograph by Erio Piccagliani

The story of Cinderella, a young woman who rises from her misfortune to marry a royal through the help of a mystical force, is a folktale known in thousands of forms. The version most familiar to the English-speaking world, however, was first published in French in 1697 by Charles Perrault (1628–1703) as part of his Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités (Tales from the past, with Morals), a collection of short stories. Written to be read by members of the French aristocracy, it seems no surprise that the story was later adapted into a full-length ballet, first by French dancer and choreographer Louis Duport in Vienna in 1813.

Frédéric-Théodore Lix (1830–1897), Cendrillon (one of four illustrations for Les Contes de Perrault), 1890. Color lithograph, printed by Garnier Frères, 9 ⅞ x 7 ¾ in. (25.1 x 19.6 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, A040975

The next notable version was choreographed for the Mariinsky Ballet by the enormously talented team of Enrico Cecchetti (act I and III) and Lev Ivanov (act II) with supervision by Marius Petipa. The score was by Baron Boris Fitinhof-Schell. Last performed in 1901, this version of Cinderella’s music was never published and is now lost, as is the 19th century choreography. From 1940 to 1944, however, Sergei Prokofiev composed a brilliant new score, taking inspiration from both Perrault’s fairy tale and Aschenputtel (1813), the Brothers Grimm’s much darker version of the story. The score has since inspired numerous choreographic interpretations, among them Alfred Rodrigues’s 1955 version for the Teatro alla Scala.

André Beaurepaire (1927–2012), Set design for the ballet Cenerentola, Act II, Teatro alla Scala, Milan, 1955–56. Watercolor on paper, 19 x 25 in. (48.3 x 63.5 cm) (sheet). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Theater and Dance Collection, gift of Alma de Bretteville Spreckels, T&D1959.30 © 2007 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

To help bring his vision to life, Rodrigues partnered with accomplished scenographer and costume designer André Beaurepaire (1924–2012), an artist known for his penchant for glamor, complex geometries, and fantasy. These qualities coalesce in his set for Cinderella, a ballet that demands splendor and imagination in equal measure. Today, Beaurepaire’s designs are preserved in his surviving preliminary drawings, such as a design for the second act held in the Fine Arts Museums’ works on paper collection. The drawing is one of many magnificent theater and dance designs purchased by Alma de Bretteville Spreckels, the Legion of Honor’s founder, in Paris in 1920 that were subsequently gifted to the museum in 1959.

At 19 x 25 inches (48.3 x 63.5 cm.), the large-scale drawing immediately conveys a sense of grandeur. With scarlet red walls and gilded ornamentation, the stage set would have echoed the red-and-gold palette of the Teatro alla Scala itself, as if fusing reality and fantasy into one lavish setting. Below an elaborate coffered ceiling, five gilt doorways tower over the room, as does an enormous golden clock, an essential element of act II. At the right, the king’s golden throne sits beneath a baldachin and a coat of arms. At left, a quartet seated in a niche tucked below a balcony strums their string instruments. Above the musicians, and around the periphery of the room, guests peer down from the second floor to watch the others dance and mingle below.

Cover of brochure for Cenerentola with a drawing by MVM. Gift of William Eddelman. Photograph by Jorge Bachman

In the ballet adaptation, it is the drama that unfolds during the second act that sets Cinderella and the prince’s love story in motion. Upon her grand entrance, she and the prince instantly fall deeply in love. Then, as her fairy godmother warned, when midnight strikes on the enormous clock, Cinderella begins to revert back to her former appearance. As the guise of the princess slips away before everyone’s eyes, she flees the ball, losing her slipper along the way.

Cenerentola, Act II, at Teatro alla Scala, Milan featuring a set design by André Beaurepaire, 1955–1956. Photograph by Erio Piccagliani

With its extreme scale and magnificence, Beaurepaire’s design creates the sense of fantasy needed for this critical moment in the story when Cinderella briefly lives in a world she has only dreamed of before returning to her own reality once more. Archival black-and-white photographs show the real-world stage sets were even more whimsical than suggested in the Museums’ colorful drawing. This undoubtedly heighted the dreamlike atmosphere of the second act, and the ballet in general. Although the 1955 version of Cinderella is no longer performed, Fracci’s breakthrough debut is still heralded as a pivotal moment in the legendary ballerina’s long career and, more broadly, in ballet history. While her interpretation of the role was certainly brilliant, much is also owed to Beaurepaire, whose magical designs also contributed to the authenticity of her performance.

Christopher Wheeldon’s Cinderella © Photograph by Chris Hardy. Image courtesy of the San Francisco Ballet

Christopher Wheeldon’s Cinderella © Photograph by Chris Hardy. Image courtesy of the San Francisco Ballet

Since the mid-20th century, many have reinterpreted Cinderella’s story. Of these reinventions, one of the best-known is by renowned dancer and choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, who was co-commissioned by the San Francisco Ballet and Dutch National Ballet to re-choreograph Cinderella in 2012. Much like Prokofiev, Wheeldon found Perrault’s storyline overly sentimental. Instead, he was drawn to the darker elements of the Brothers Grimm’s tale. Leaving behind the fairy godmother and pumpkin coach, Wheeldon tells the story of a hopeful young woman guided by the mystic powers of the forest and the spirit of her deceased mother. Thanks to the combined expertise of costume designer Julian Crouch and the great puppeteer Basil Twist, the set made to accompany the ballet is a miracle of scenography. It abounds in mesmerizing visual effects and gorgeous decor, such as the numerous chandeliers of the second act that reflect those in Beaurepaire’s earlier design. Perhaps most astounding is an enormous tree at the close of act I that billows and grows before the audience’s very eyes. From March 31, 2023, to April 8, 2023, San Francisco Ballet will be bringing Wheeldon’s Cinderella back to the War Memorial Opera House’s stage. Not to be missed, this centuries-old fairy tale reimagined for our time promises to be an unforgettable experience and a true feast for the eyes.

Clip from act II of Christopher Wheeldon’s Cinderella featuring principal dancers Sasha De Sola and Luke Ingham

Text by Sarah Mackay, assistant curator of prints, drawings, and photographs.