Views of Naples: Thematic Decoration of an Eighteenth Century Porcelain Dinner Service

By Thomas Wu

August 12, 2021

As the hyper-contagious Delta variant threatens to complicate overseas travel once again, museums offer a local alternative for those who yearn to experience something different from their usual surroundings. In 2017, a supporter gave the Fine Arts Museums two dinner plates from the Views of Naples Service produced by the Naples Royal Porcelain Manufactory (1771–1806) ca.1792–1795 for King Ferdinand IV of Naples. To augment this significant gift, two groups of porcelain figures that once formed part of the service’s centerpiece were acquired in 2019. Although just fragments of the four-hundred-piece service, these plates and figures exemplify the imaginatively themed porcelain services produced during the eighteenth century and offer visitors to the Legion of Honor little windows onto the Bay of Naples.

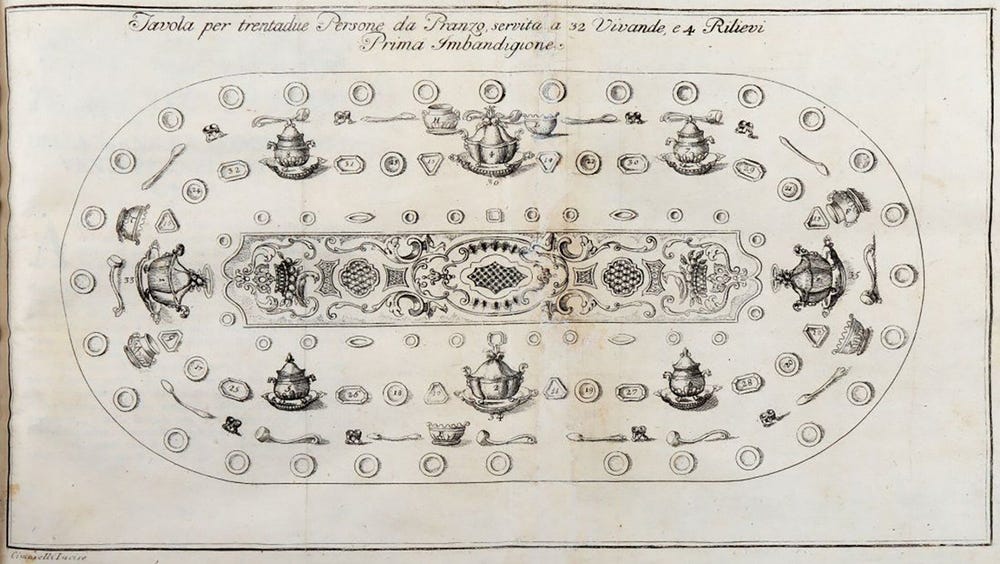

Royal porcelain dinner services included all of the wares needed for an elaborate banquet, except for stemware and silver cutlery. As illustrated in table plans from Il cuoco galante, a dining manual published in 1773 by Vincenzo Corrado (1736–1836), who planned banquets at the Neapolitan court, a service would have been arranged concentrically on a table. The outermost tier would have comprised individual plates corresponding to the number of diners. A middle tier would have included shared serving dishes, such as tureens or sauce boats, while a sculptural centerpiece would have formed the innermost tier. The plates and figures in the FAMSF collection correspond to the Views of Naples Service’s outermost and innermost tiers, respectively. The design and decoration of a service, including its shapes, colors, patterns, and imagery, often embodied a central theme, such as “Classical,” “Etruscan,” or “Egyptian.” The wares and centerpiece of the Views of Naples Service adhere to a Neapolitan theme and together would have presented a broad survey of famous sights in Ferdinand IV’s domain.

Table plan from Il cuoco galante by Vincenzo Corrado, Naples, 1773. Image Wikimedia

The center of each plate depicts a different landmark around the Bay of Naples. One plate depicts unidentified ruins that closely resemble the ancient Greek temple of Hera at nearby Paestum. During the eighteenth century, as today, Naples was one of Europe’s most archaeologically significant regions. It was settled by Greeks during the second millenium B.C., who later established the city of Neápolis around the seventh century B.C. The city was incorporated into the Roman Empire in 326 B.C. and cherished by the Romans as a center of Hellenistic culture. Wealthy Romans built lavish, frescoed villas at nearby Pompeii and Herculaneum, famously destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. Excavations at Herculaneum begun in 1738 were published in an eight-volume book of engravings titled Antiquities of Herculaneum Exposed (1757–1792), which would inspire Neoclassical architecture and art across Europe from Britain to Russia. Although not a great imperial power during the eighteenth century, the Kingdom of Naples exerted disproportionate cultural influence through its archaeological riches.

Plate depicting the ruins of an ancient Greek temple. Royal Naples Porcelain Manufactory, ca. 1793-95. Porcelain. Gift of Mary S. Rodgers in memory of Bertram J. Rogers, Jr. 2017.13.2. © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The other plate at the Legion of Honor depicts a casina, or hunting lodge, at Lake Fusaro on the outskirts of Naples, designed by Luigi Vanvitelli in 1782. Naples was not only notable during the eighteenth century for its ancient legacy, but also as a thriving metropolis graced by imposing Renaissance and baroque palaces and churches. It was the third largest city in Europe, after London and Paris, and one of the busiest ports on the Mediterranean. Naples was also a leading center of art, cuisine, and, especially, music and theatre. Two styles of opera popular during the eighteenth century, opera seria and opera buffa, were developed in Naples, while the city’s Teatro di San Carlo, completed in 1737, remains the oldest opera house in use today. Although dominated by the houses of Hapsburg (Spain and Austria) and Bourbon (France), Naples had the distinction of being the largest territory on the Italian peninsula and the only kingdom. Other plates and serving wares from the service, displayed in the Capodimonte Museum, where the Royal Porcelain Manufactory was once housed, depict other ancient and modern landmarks, as well as natural landmarks. If the decoration of these wares was limited only to ancient or modern or natural sites, the service would not capture the full glory of Ferdinand IV’s realm, past and present.

Plate depicting a casina on Lake Fusaro. Royal Naples Porcelain Manufactory, ca. 1793-95. Porcelain. Gift of Mary S. Rodgers in memory of Bertram J. Rogers, Jr. 2017.13.1. © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The forms, border patterns, and colors of the service’s plates and serving wares also conform to its Neapolitan theme. The smooth, rounded edges of the plates are in keeping with the Neoclassical style that was so strongly influenced by the unearthing of Herculaneum. The edges differ from the undulating edges of mid-eighteenth-century rococo wares. It is not likely coincidental that the colors of the plates’ borders—red, gold, and blue—are also those of the Neapolitan coat of arms under the Bourbons. Crucially, while the service’s plates and serving dishes depict a variety of subject matter, the service is visually and thematically unified by consistent borders and edges.

Coat of arms of the House of Bourbon in Naples. Image Wikipedia.

The two groups of figures in the FAMSF collection formed part of the service’s sculptural centerpiece and depict bourgeois (upper-middle-class) families seated on benches lining the Royal Promenade in the Villa Comunale, a royal park situated along the bay that was open to the public on certain holidays. They sport the latest fashions: The women and girls wear gaulles, simple muslin dresses made popular by the French queen Marie Antoinette, whose sister, Maria Carolina of Austria, was, incidentally, the consort of Ferdinand IV and the de facto ruler of Naples. These happy scenes, captured by the centerpiece, demonstrate the king’s benevolence in opening a royal park to his subjects. The figures also introduce a key element of Naples that the plates, with their depictions of monuments, lack: its people.

(Left) Benches in the Royal Promenade. Royal Naples Porcelain Manufactory, ca. 1792-94. Porcelain. Museum purchase, San Francisco Ceramic Circle and European Decorative Arts Trust Fund. 2019.16.1. (Right) Benches in the Royal Promenade. Royal Naples Porcelain Manufactory, ca. 1792-94. Porcelain. Museum purchase, San Francisco Ceramic Circle and European Decorative Arts Trust Fund. 2019.16.2. Photographs by Randy Dodson, © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

To guests attending a banquet at the Palace of Capodimonte, the plates, serving wares, and centerpiece of the Views of Naples Service would together have boasted of Naples’s enviable classical heritage, modern culture, thriving economy, and dramatic scenery, all framed by the heraldic colors of her reigning house. The service would itself have been evidence of Naples’s achievement, including the establishment of a porcelain factory to rival those at Sèvres in France and Meissen in Saxony. Within the FAMSF collection, these plates and figures are rare examples of the extensive, coordinated services used for royal banquets during the eighteenth century. We hope that these pieces will transport viewers today, as then, to a sunny bench in the Villa Comunale overlooking the sparkling, bustling Bay of Naples.

Article by Thomas Wu, curatorial assistant, European Decorative Arts and Sculpture, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Click here to learn more about the archaeological legacy of the Bay of Naples.