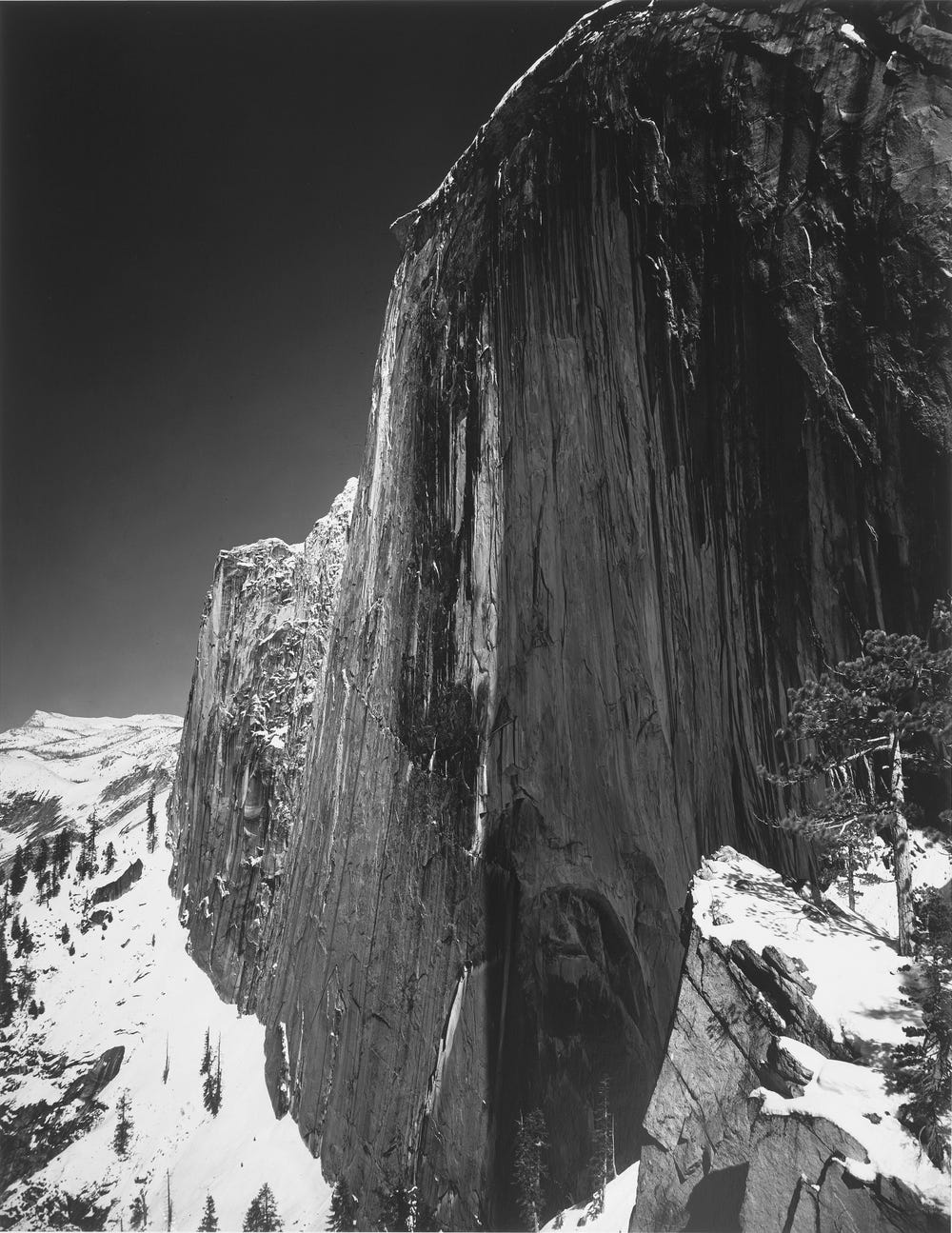

Ansel Adams (1902–1984), Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park (detail), ca. 1937. Gelatin silver print, Framed: 15 1/8 x 19 1/8 x 1 5/8 in. (38.418 x 48.578 x 4.128 cm), Image: 7 3/8 x 9 1/4 in. (18.733 x 23.495 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The Lane Collection. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Ansel Adams, the San Francisco–born landscape photographer, first witnessed environmental destruction as a young boy, when the US Army Corps of Engineers cleared a stand of oak trees along one of his family’s favorite hikes in SF’s Presidio. He joined the California-based Sierra Club at the age of 17. Adams dedicated his life to conserving nature, advocating for protection of wilderness areas and the establishment of national parks. While his advocacy included essays, letters, speeches, and trips to the US Congress, his powerful landscape photos are ultimately his most enduring contribution to environmental preservation.

Ansel Adams (American, 1902–1984), Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park, about 1937. Gelatin silver print, Framed: 15 1/8 x 19 1/8 x 1 5/8 in. (38.418 x 48.578 x 4.128 cm), Image: 7 3/8 x 9 1/4 in. (18.733 x 23.495 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The Lane Collection. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust, Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

“I knew my destiny when I first experienced Yosemite,” Adams wrote in his autobiography. He took his very first photographs in Yosemite and returned to it repeatedly throughout his life. The park was central to both his photography and his environmental activism. In the Yosemite captured in Adams’s photographs, Yosemite Falls crashes down torrentially, a winter storm clears over Inspiration Point, and Half Dome rises like a monolith over the snow-covered Tenaya Peak. Adams framed his photographs to cut out any trace of human activity, evoking untouched wilderness. His photographs raised public awareness and drew support for protecting Yosemite Valley.

Ansel Adams, “The Role of the Artist in Conservation,” 1975Response to natural beauty is one of the foundations of the environmental movement.

Ansel Adams, (1902–1984), Monolith – The Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, 1927; print date: 1950–60. Gelatin silver print, Framed: 31 1/8 x 25 1/4 x 2 1/4 in. (79.058 x 64.135 x 5.715 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The Lane Collection © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Yet Adams’s images of Yosemite were not completely true to life. While he framed his photographs to cut out any trace of human activity, Yosemite was not a wilderness untouched by humans. In fact, the Ahwahnechee and other Indigenous peoples had lived in Yosemite for thousands of years before the Gold Rush brought in white settlers, the US Army, and militias. By the 1920s, visitors to the park were largely tourists, and Adams’s photographs were used as promotion to draw them in.

With increased tourism came increased development. Construction of roads, power lines, guest housing, and campgrounds made the park accessible to a growing volume of visitors, at the expense of preservation. Adams supported the idea of visitors to the park, but fought against increased development. He was especially devastated by construction on a road in the Tenaya Lake area, which required blasting through three miles of natural granite. Adams sent a slew of letters protesting the development, which he called a “desecration.” He supported prohibiting personal vehicles from Yosemite altogether and implementing a shuttle system. Owing in part to the advocacy of Adams and other environmentalists, some of the developments in the park were rolled back. When cars were prohibited from certain areas in 1970, Adams, then 68, hiked out with his camera to capture the demolition of an obsolete parking lot.

Adams’s dedication to preservation extended far beyond Yosemite. He fell in love with California’s Kings Canyon on multiple trips to the region, calling Marion Lake in particular “the most beautiful thing [he had] ever seen.” Kings Canyon had been afflicted by mining, logging, and grazing, and the region was further threatened by applications from the City of Los Angeles to construct hydroelectric dams. The Sierra Club advocated for making Kings Canyon a national park so it could be better protected, and Adams was chosen to represent the club at a conference in Washington.

Ansel Adams, (1902–1984), Marion Lake, Kings River Canyon, California (from Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras), ca. 1925; print date: 1927. Gelatin silver print, Framed: 17 1/8 x 21 1/8 x 1 in. (43.498 x 53.658 x 2.54 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, The Lane Collection. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

To make his argument, Adams presented a selection of his own photographs before the assembled representatives. “My unsophisticated presentation of the photographs, coupled with appropriately righteous rhetoric, stirred considerable attention in Congress for our cause,” Adams would later remark. When some of his Kings Canyon photographs were collected in a book, Adams sent a copy to Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes. Ickes brought out the book frequently in his continued lobbying on behalf of Kings Canyon, and asked Adams for a new copy when the president insisted on keeping the first one. Four years after Adams’s trip to Washington, Kings Canyon was finally made a national park.

Ansel Adams, Ansel Adams: An Autobiography, 1985There is so much absolute beauty along the California coast that I could work for a century, exploring with eye and lens.

Later in his life, Adams settled down in Big Sur, a stretch of rugged California coastline famous for its sheer cliffs and crashing waves. In what has been described as his “last battle,” Adams helped found the Big Sur Foundation and served as vice president for the remainder of his life. The foundation opposed encroachments on Big Sur’s natural landscape, such as mining its mountains for limestone, widening Highway 1 to make room for more traffic, and constructing new hotels and houses. “[The Big Sur Coast] is undoubtedly among the most beautiful of the untouched lands and certainly should be secured and protected for the future,” wrote Adams. He remained a strong supporter of Big Sur’s protection until the end of his life. The Big Sur Local Coastal Plan, which provides rigorous limitations on development, was passed in 1986, only two years after he passed away.

Catherine Opie, Untitled #4 (Yosemite Valley), 2015. Pigment print, Framed: 31 1/8 x 46 1/8 x 2 1/8 in. (79.058 x 117.158 x 5.398 cm. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

Adams himself may be gone, but the fight against environmental destruction lives on. In California alone, the same landscapes lovingly photographed by Adams are threatened by wildfires, oil drilling, logging, droughts, land development, and rising ocean levels. A new generation of photographers has taken up the cause of environmentalism. California-based artist Catherine Opie takes deliberately out-of-focus pictures to show landscapes that are fading from view, perhaps being lost to environmental destruction. Mark Klett re-creates 19th- and 20th-century landscape photographs, replicating the location and conditions of the originals as closely as possible. The resulting time-lapse images show the impact of climate change. David Benjamin Sherry creates photos that are saturated with a single color. Sherry’s works grapple with environmental destruction, but also reference American optimism through the use of bright colors. Through these photographers, Ansel Adams’s artistic and environmental legacy endures today.

Text by C. Zane Heard, data services assistant.