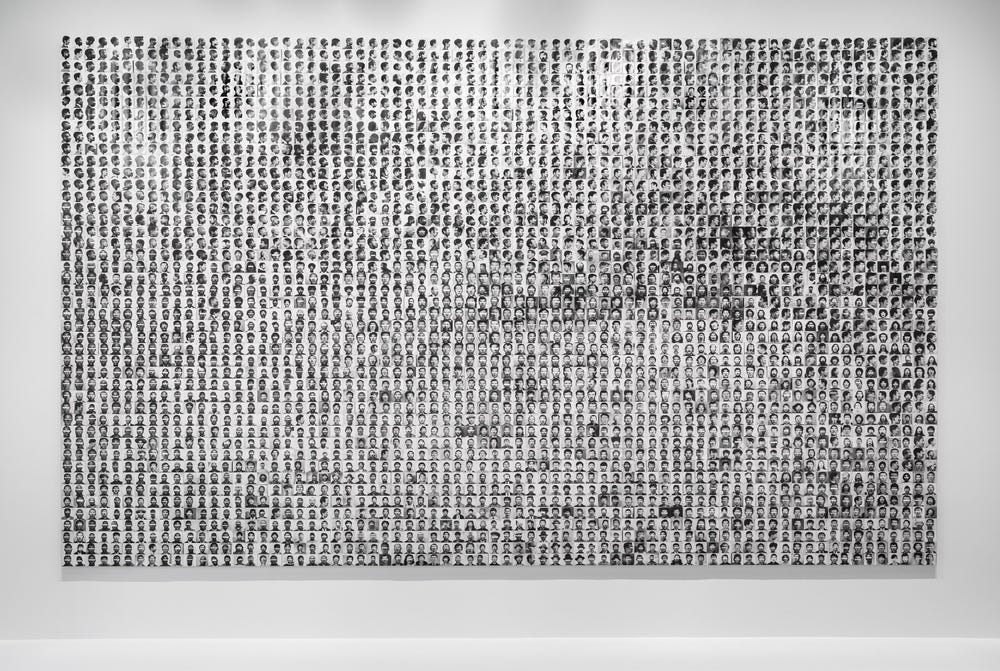

Trevor Paglen, “They Took The Faces From The Accused And The Dead . . . (SD18)”

By Claudia Schmuckli

June 19, 2020

With nearby Silicon Valley driving the development of artificial intelligence, or AI, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI is the first major museum exhibition to reflect on the political and philosophical stakes of AI through the lens of artistic practice. This series highlights select artworks included in the exhibition.

Informed by his training as a geographer, Trevor Paglen has focused his investigative lens on the physical sites and material infrastructures underpinning the networks of power that monitor and control society. His photographs of military black sites, offshore prisons, underwater cabling, and surveillance drones derive their impact from the tension between what is seen and unseen. His subjects often project a surface banality that belies their function as secret harbors of civil surveillance and warfare. The images are rendered to evoke a sense of the sublime that recalls traditions of nineteenth-century landscape photography and reinforces this incongruity.

Trevor Paglen, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead . . .(SD18), 2020. 3,240 silver gelatin prints and pins; dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Altman Siegel, San Francisco

More recently, Paglen has turned his attention to the mechanisms of computer vision and its use in AI systems deployed to automate and optimize the operations of states and industries. He is especially concerned with the tools developed to train these systems: image sets that represent and interpret human beings. This topic was the subject of the 2019 exhibition Training Humans, which Paglen conceived with AI researcher Kate Crawford. In a publication accompanying the exhibition, they write, “Training sets are available, by the thousand, presenting their data as unproblematic—just a set of images and labels that are somehow neutral and scientific. Part of our project is to open up this substrate of images, this underworld of the visual, to see how it works at a granular level. Once inside this world, we can observe how training data sets have biases, assumptions, errors, and ideological positions built into them. In short, AI is political.”1

Training Humans traced the history of training images from the 1960s to today. It began with CIA-funded programs and proceeded to recent data sets whose contents have been scraped from social-media accounts without their owners’ explicit permission or consent. Collectively, these images form what Paglen and Crawford call a “machine vernacular”—photographs taken from the everyday, never meant to be seen by humans, and used solely for the purposes of machine identification and pattern recognition. Training Humans also included ImageNet Roulette (2019), a computer-vision system designed by Paglen that draws on ImageNet, a data set launched in 2009 to “map out the entire world of objects.”2 ImageNet contains more than twenty thousand categories, each containing an average of one thousand images, to total more than fourteen million images. Among them are roughly two thousand “types” of people, whose attributes continue to be determined by crowdsourced labor with no consideration given to workers’ inherent cultural or social biases. ImageNet Roulette encouraged people to upload pictures of themselves to find out how they would be classified by the data set’s qualifiers. The results that participants received were permeated by value judgments related to class, gender, and race, making the process an eye-opening “lesson . . . in what happens when people are categorized as objects.”3

In Paglen’s related installation From Apple to Kleptomaniac (Pictures and Words) (2019), the artist engulfed viewers in a crosssection of ImageNet’s “world of objects” through thirty thousand images individually printed and pinned to the walls of the exhibition space. As viewers perused the materials, their curiosity may have turned into consternation as they observed the prejudice and judgment inherent in the system’s classifications of people. As Paglen and Crawford point out, an uncritical reliance on image training sets reprises problematic uses of photography popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. During this period, an assumption of photography’s objectivity, combined with ideas of social Darwinism, gave birth to disciplines like physiognomy and phrenology, which posited that morals and intelligence could be determined through one’s physical and behavioral features. The negative implications of such belief systems were fully realized in the anthropometric experiments of criminologists Cesare Lombroso and Alphonse Bertillon. Lombroso, an Italian professor of criminology, espoused the now discredited idea that one’s criminal nature could be determined solely by physical characteristics, while Bertillon, a French police officer, created an identification system for criminals based on their physical metrics that later gave way to the practice of fingerprinting.

Trevor Paglen, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead . . .(SD18), 2020. 3,240 silver gelatin prints and pins; dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Altman Siegel, San Francisco

Paglen’s They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead . . . (SD18) highlights the American National Standards Institute database, whose archives of mug shots, featuring those convicted and those merely accused, once served as the predominant source of visual information for facial-recognition technology (a role now filled by social media). The institute gave developers access to its database to test and evaluate their algorithms. In other words: originary facial-recognition software was built from images of prisoners repurposed by the US government without their consent. The work criticizes this violation of privacy at the core of facial-recognition technologies and the institutional bias perpetuated by the training data. The work consists of a large gridded installation composed of more than three thousand individually pinned silver gelatin prints. The images are organized by an AI-determined system of formal similarities that makes visible its underlying methods of classification. The work’s schematizing black-and-white aesthetic deliberately invokes the work of Lombroso and Bertillon, establishing a haunting parallel between their earlier projects and contemporary uses of photography within machine learning.

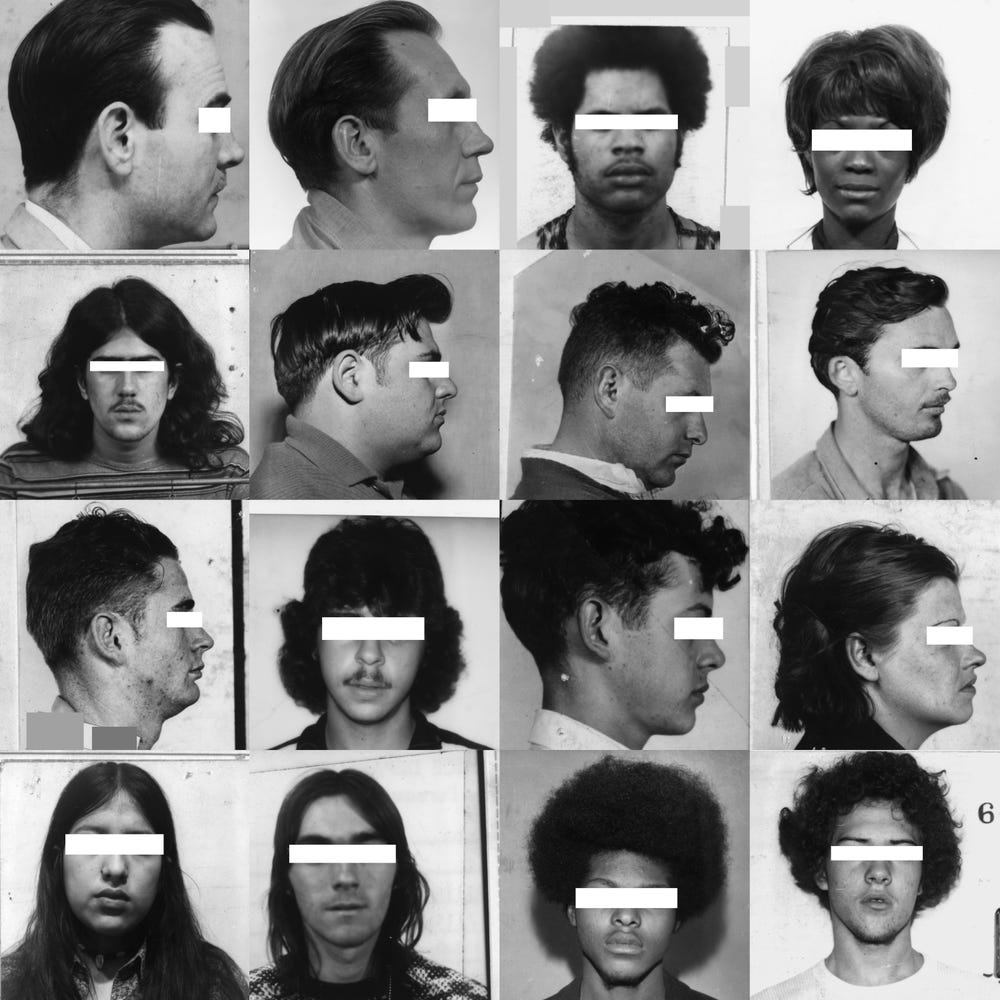

Trevor Paglen, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead . . .(SD18), (detail), 2020. 3,240 silver gelatin prints and pins; dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Altman Siegel, San Francisco]

Text by Claudia Schmuckli, Curator in Charge of Contemporary Art and Programming; from Beyond the Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Available for purchase through the Museums Stores.

Learn more about Uncanny Valley at the de Young museum.

Further Reading

- “Conversation by Kate Crawford and Trevor Paglen,” in Training Humans, Notebook 26 (Milan: Fondazione Prada, 2019).

- “The Data That Transformed AI Research—and Possibly the World,” Quartz, July 26, 2017, https://qz.com/1034972/the-data-that-changed-the-direction-of-ai-research-and-possibly-the-world.