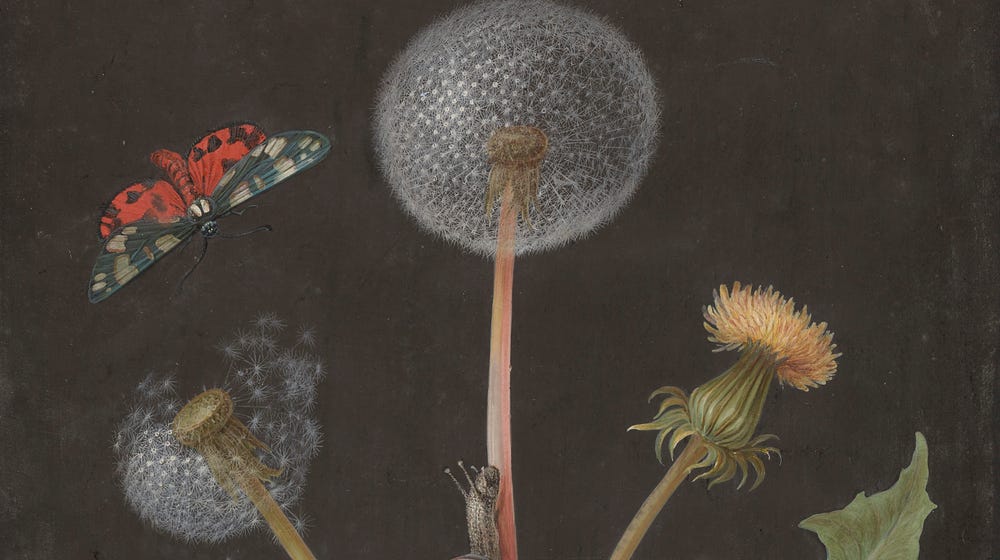

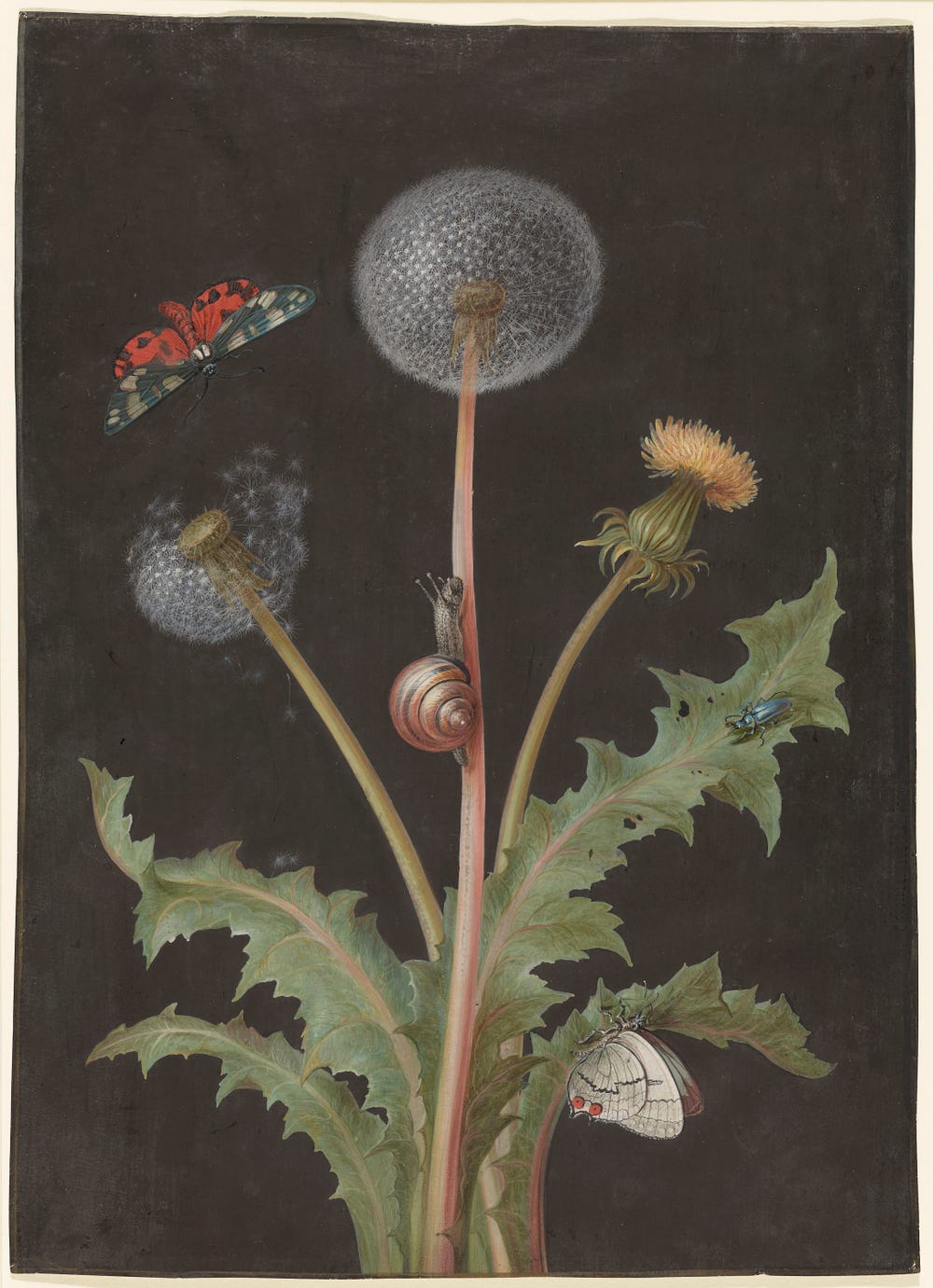

The Wild Inventiveness of Barbara Dietzsch: a Dandelion with a Tiger Moth, a Snail, A Beetle, and a Butterfly

By Furio Rinaldi

April 21, 2021

Earth Day 2021 reminds us that the natural world is a powerful source of wonder and delight. A seventeenth-century work on paper from the Museums’ collection invites us to ponder our ecosystem, its cyclicality, fragility, resilience, and beauty. A Dandelion with a Tiger Moth, a Snail, a Beetle, and a Butterfly, one of the highlights of our graphic holdings, is a gouache (watercolor mixed with white lead) on vellum work realized ca. 1750 by the German botanical artist Barbara Regina Dietzsch (1706–1783). Hailed as one of the greatest painters of still life in early modern Europe, Dietzsch was the head of a productive, successful workshop in Nuremberg, Germany, a departure from the patriarchal structure of traditional art-making of her time.

Randy Dodson, © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Cycles

A testament to the artist’s sensitivity to the most minute aspects of the natural world, this still life reflects Dietzsch’s detailed approach, which reveals itself with a closer look. This botanic arrangement does not depict one single branch of dandelion, as it appears at a first glance, but rather three separate stems, each depicted in a different stage of its life cycle. On the right, we see the dandelion as a flower, already in the process of drying out. It is being replaced by the towering stem at the center, characterized by the fully formed sphere of its fluffy seed head. Spoiled by a breeze, or perhaps by the tiger moth approaching from above, the branch on the left records the moment when the seeds are detaching from the head and being dispersed by the wind.

Disguised as a formulaic arrangement of flowers and insects, Dietzsch’s dandelion can be read as an ode to nature’s cyclicality and its ability to regenerate itself. In the artist’s still lives, dandelions are a recurring motif, possibly chosen for their fragile beauty. Nevertheless, the presence of three separate stems makes the sheet in the Museums’ collection particularly rare. Dietzsch’s example at the Getty Museum depicts only two stems, a simpler composition that was replicated at her Nuremberg workshop, as attested by the sheets realized by her sister Margaretha Barbara at the British Museum in London, and her pupil Johann Christoph Bayer at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

Randy Dodson, © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Randy Dodson, © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Fragility and Strength

The fragile beauty of the dandelion’s feathery seed head constitutes the attractive center of this composition. While celebrating its marvelous shape, the artist hinted that only when the dandelion’s delicate perfection is spoiled (thus allowing the dispersal of the wind-borne seeds) can the plant’s regeneration and ultimate survival occur. The leaf belonging to the central dandelion leads us to notice a surprising contrast. Eaten by a beetle and punctuated with holes, this imperfect leaf seemingly diminishes the glorious appearance of the towering dandelion. However, this contrast underscores the plant’s function: It is not a self-serving specimen, but rather the center of a larger ecosystem of flora and fauna that revolves around it—and depends on it.

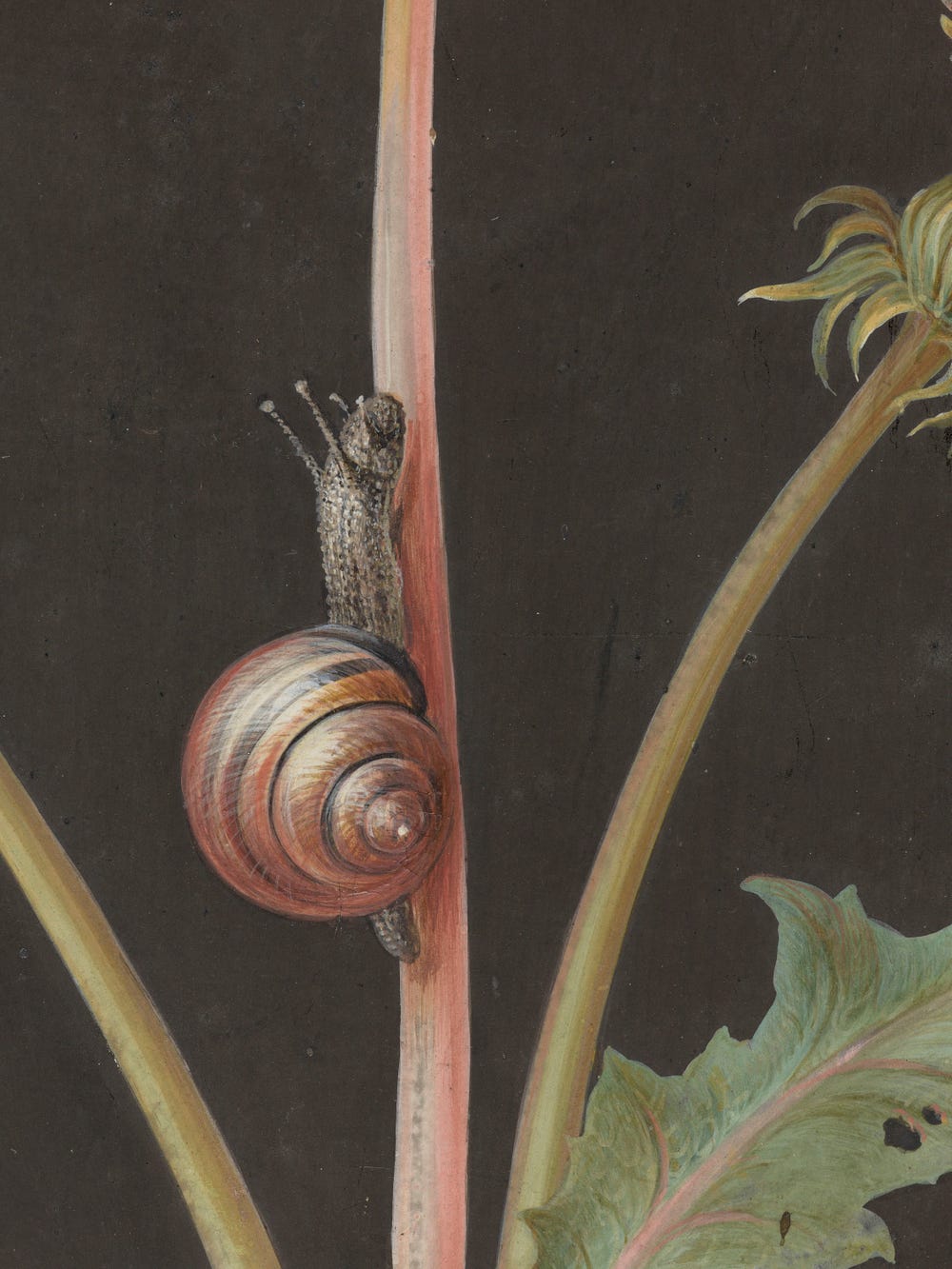

The name “dandelion” derives from the notched shapes of the plant’s leaves, which resemble the teeth of a lion, or “dent-de-lion,” as the plant is known in France. (In Germany it is known as “löwenzahn” and in Italy as “dente di leone.”) Just like a lion, the leaves and stems of a dandelion are particularly tenacious, strong, and, in Dieztsch’s depiction, sturdy enough to withstand the simultaneous presence of a butterfly, a snail, and a beetle. The incongruent presence of several creatures belonging to different environments, temperatures, and humidity levels further highlights how the dandelion, even with its apparent fragility, represents a shelter for a vital entomological community.

Dietzsch’s gouaches always provided such an ecological perspective, because she studied and illustrated plants and animals in their natural setting. Owing to their intrinsic beauty and fidelity to nature, her works were sometimes engraved and reproduced in botanical and entomological treatises of the period (like Christoph Jacob Trew’s Hortus Nitidissimus, printed in Nuremberg in 1750).

Randy Dodson, © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Randy Dodson, © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Dietzsch’s world

Born in 1706 in Nuremberg, Barbara Regina Dietzsch was the eldest of seven children in an artistic family. As usual for women artists of the time, she was first trained by her father, the landscape painter Johann Israel Dietzsch. In turn, she taught the art of still life and gouache painting to her younger sister Margaretha Barbara (1726–1795), who followed her style, becoming an accomplished engraver and botanical artist in her own right.

Dietzsch depicted objects from the natural world (plants, insects, and sometimes birds, live or stuffed), always life-size, taking notice of the smallest details. While historically the genre of still life was tied to moral and religious meanings, often pertaining to the brevity of earthly life, Dietzsch instead focused on the simplicity, beauty, and wonder of natural structures, without adding any mythical or religious symbolism to her compositions. Her jewel-like gouaches feature refined and theatrical arrangements of flowers and animals, characterized by intense pictorial light and a detailed three-dimensional finish. The artist chose to always depict her delicately refined groupings against a black or dark-brown background, a decision that emphasized the color and shape of the plants while also infusing a sense of drama into the composition. The addition of a velvety dark background became the trademark of her workshop and was adopted by her pupils and many followers, including her sister and Elisabeth Christina Matthes. Dietzsch provides us with a typical example of an emancipated woman in early modern Europe; she enjoyed complete autonomy in the practice of her art and experienced tremendous success with her work, even outside Germany.