The Weight of Weaving: A Closer Look at Olga de Amaral’s “Lost Image 17”

By Julieta Fuentes Roll

December 9, 2021

I didn’t know what to expect as I began my summer internship at the de Young museum within the costume and textiles department. I was both nervous and thrilled. I worried that the space might prove to be inaccessible to me as an undergraduate student. This opportunity was special to me as an anthropology major at the University of California, Berkeley; working at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco felt like a dream. One of my tasks was to conduct research on an object of my choosing. I searched for an intriguing piece from Latin America, as I felt it was important to bring my Mexican American lived cultural experience into my research. When I laid eyes on Olga de Amaral’s Lost Image 17, I knew I had found my muse.

Olga de Amaral (1932– ) is a textile artist from Bogotá, Colombia. She studied architecture in the United States before returning to Bogotá to pursue her craft. Since the beginning of Amaral’s career, her work has been an extension of the self. Building off the traditional craftsmanship of Latin American weaving that was typically seen as “women’s work,” Amaral pushes the boundaries of what we define as “fine art.” Intertwined in her textiles are reflections of culture, gender, and how we understand our place in the world. In studying Amaral, I came to better understand both the political and social weight a textile can carry.

Olga de Amaral, Lost Image 17, 1992. Linen with acrylic paint and applied gold and silver leaf; plain weave, oblique interlacing, 42 x 61 in. (106.7 x 154.9 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Anonymous Gift, 1994.178

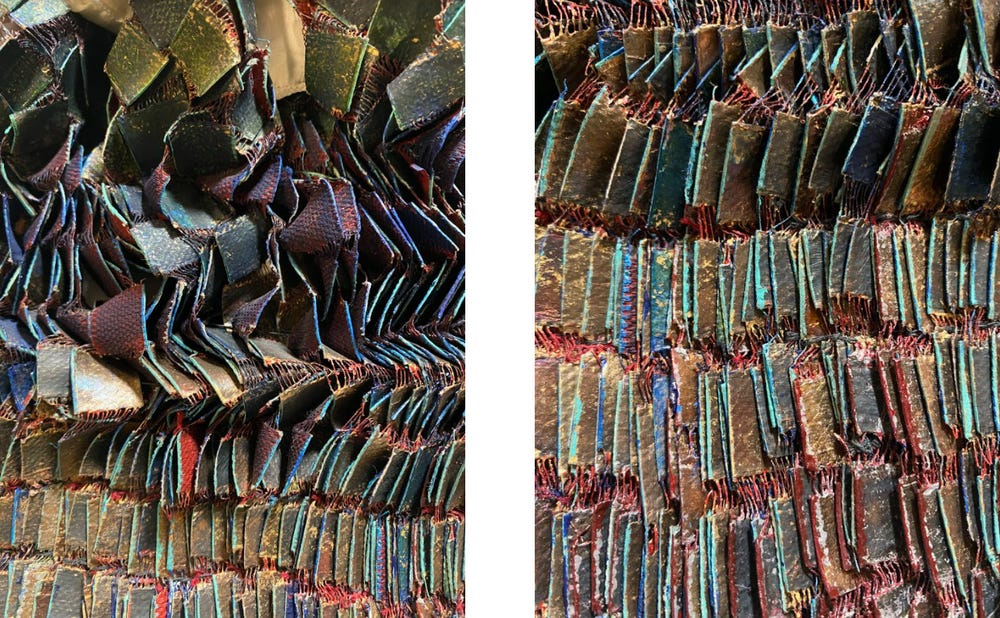

Lost Image 17 can best be described as a sculptural textile. The piece is massive and consists of a linen grid structure painted with acrylic and coated with Amaral’s signature gold and silver leaf. Lost Image 17 was finished in 1992 and was most recently displayed at the de Young in 2018. This is one of the later, mellower pieces in Amaral’s Lost Images series. It is a prime example of the intricate textured style she is most recognized for. Photographs do not do it justice. Only when I had the opportunity to view Lost Image 17 in person was I able to fully grasp its power. It consists of a copper, yellow, and greenish ombre rectangle with fringe on the bottom. In the light, it shimmers with silver and gold notes like fish scales. The linen and acrylic layers make the piece physically stiff, yet it is alive in its visual glimmer. Like a shiny ornament, Lost Image 17 is a beacon. The title descriptor “Lost” appears contradictory considering its presence, yet I enjoyed this puzzling contrast. It is not hard to see how Amaral views craft and fine art as one in the same.

Olga de Amaral, Lost Image 17 (details), 1992. Linen with acrylic paint and applied gold and silver leaf; plain weave, oblique interlacing, 42 x 61 in. (106.7 x 154.9 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Anonymous Gift, 1994.178

Amaral’s work gave me a sense of empowerment. I admired her boldness. Considering the time period in which she started working, I could imagine the uphill battle she faced against Western ideals of “high art.” Yet, she continued. In his article Female Iconoclasts in Artland, writer Anthony Giannelli poses this question:

—Anthony GiannelliEven if these creations are craft at their core, does that make them of any less value culturally or monetarily?

This question speaks to the broader commentary of which artworks and artists society deems valuable and worthy of recognition. Why does an art piece like Lost Image 17 being “craft at its core” determine its cultural worth? What historical power dynamics are behind weaving not being recognized as fine art? Although how we perceive skill and value is shifting to be more inclusive of different perspectives, I felt it was important to keep this concept in mind when conducting my research. In this context, we can critique Amaral as well. She had the ability to pursue a career as an artist, but how many artisan workers, particularly weavers, go unrecognized? I pose this question in an effort to highlight that we must always think critically about the work we are engaging in.

During my internship, the museum staff transformed my apprehension by making the textile department an inclusive and welcoming space, and Amaral’s work encouraged me to explore my own identity as a Mexican American and how I relate my cultural experience to my art. I hope to embody her determination and radiance as I move through my life. Lost Image 17 is a testament to the many stories textiles carry and what they can tell us about ourselves and the world. While they may be hidden at first, those stories are there, lingering beneath the fabric.

Text by Julieta Fuentes Roll, textiles intern, artist, and student.

Learn more about costume and textile arts.

References

Giannelli, Anthony. (2021, June 25). “Female iconoclasts: Olga de Amaral.” Artland, June 25, 2021. https://magazine.artland.com/female-iconoclasts-olga-de-amaral/.

Janeiro, Jan. “Olga de Amaral: The Artist as Alchemist.” Surface Design Journal, Spring 1989.

Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá.

Olga de Amaral: Cuatro Tiempos. Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá, 1994.

Talley, Charles. “Olga de Amaral.”

Armitano Arte 14. Bogotá: 1992.