Shaping the Land: Wayne Thiebaud’s Ponds and Streams

By Lauren Palmor

May 20, 2021

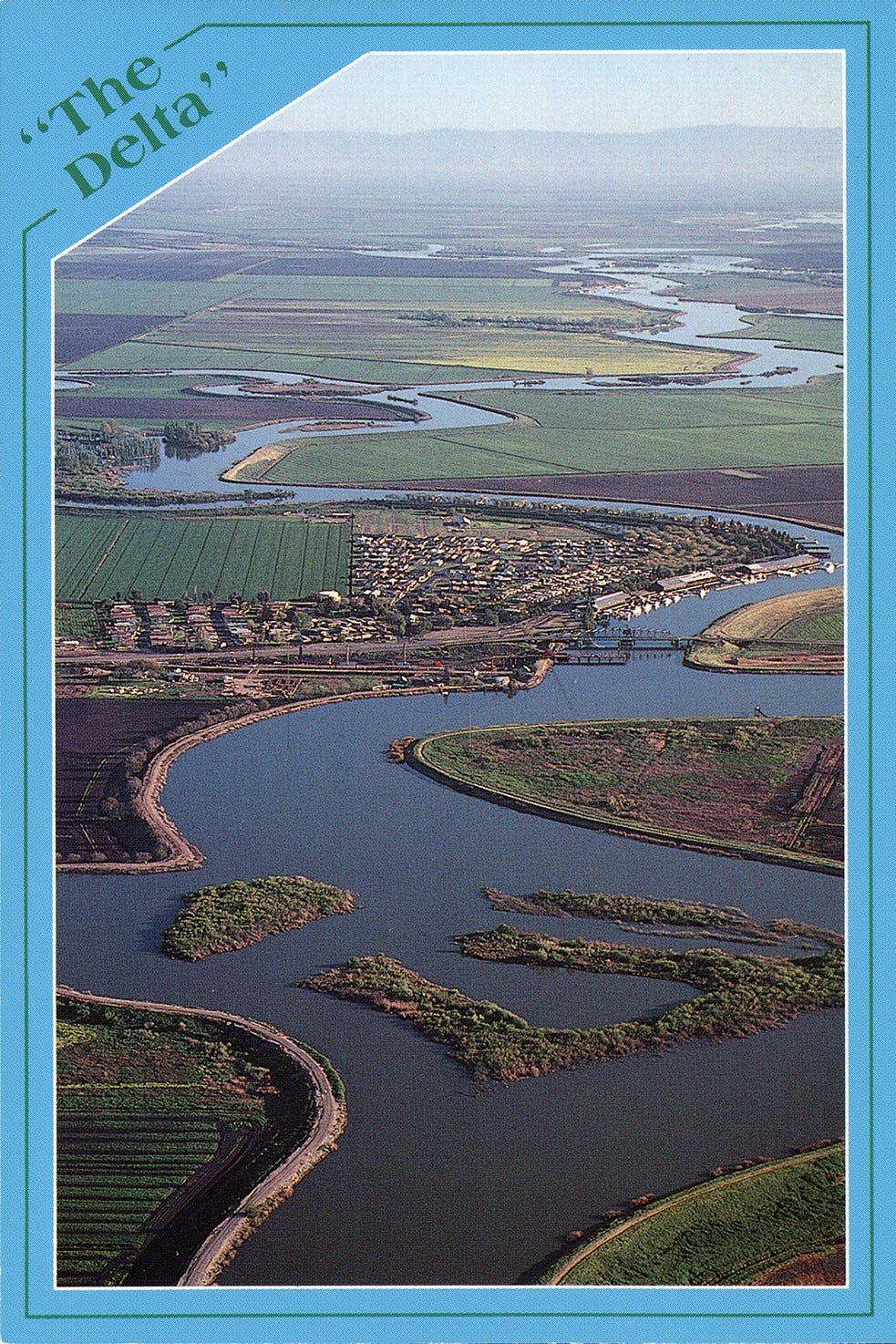

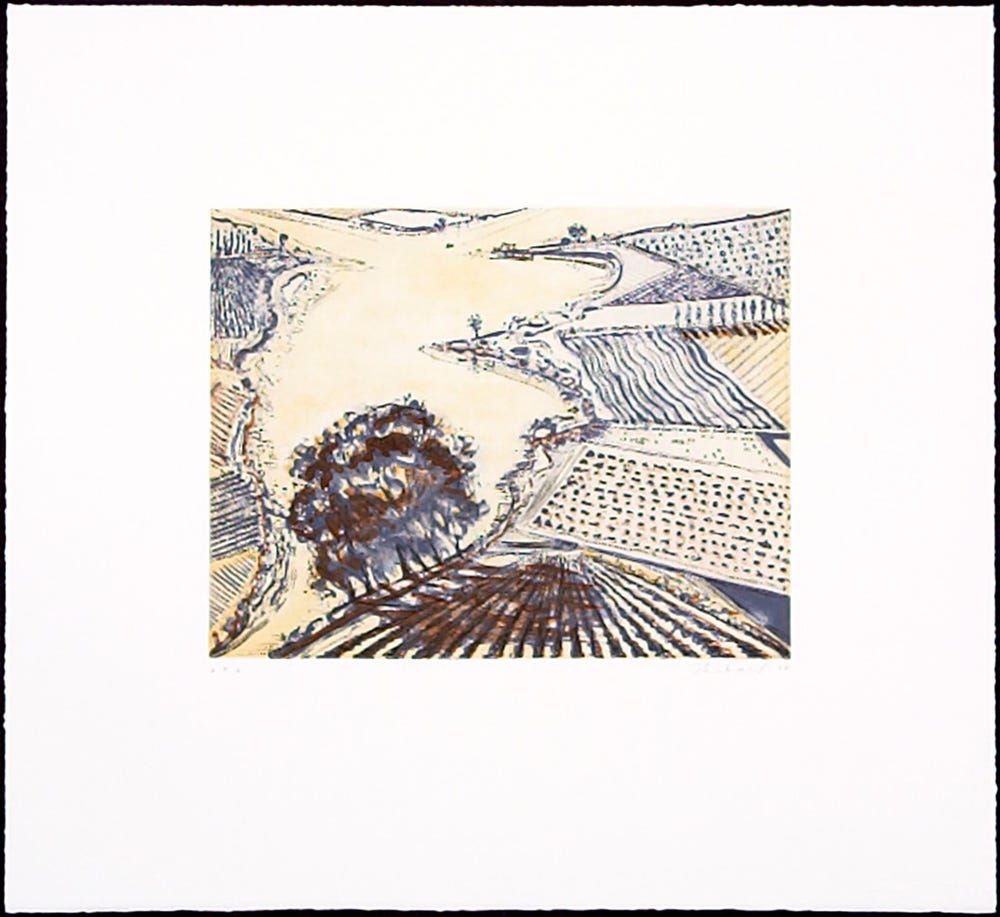

Wayne Thiebaud’s Ponds and Streams (2001) offers a disorienting, aerial view of a patchwork of intensely cultivated fields and bending waterways spread across farmland in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta. The original natural environment has been practically obliterated and subsumed within industrial agriculture: this agricultural landscape, with its orchards, pastures, and row crops, stands in place of former freshwater wetlands and channels that have been reshaped to accommodate the needs of both small-scale and corporate farms that grow many of the fruits, vegetables, nuts, and grains that end up on our plates. In addition to its bountiful farmlands, this area is also home to natural habitats, managed wetlands, and both urban and rural communities — it is truly a microcosm of what makes California special.

Art © 2021 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS) / VAGA, New York, NY

The wonderful patterns and design motifs that crop up in agriculture fascinate me.— Wayne Thiebaud

Smith-Western Co. Postcard: Arial view of miles of "The Delta,” ca. 1998, ca. Photograph by Kyle S. Smith. Courtesy of the Center for Sacramento History

Thiebaud approaches this subject as an artist who has deep personal connections to the agricultural landscape. As a child, he spent time on his family’s farm in Hurricane, Utah — a venture that failed during the Great Depression. In the 1990s, as a resident of the delta region, Thiebaud began working on a series of landscapes depicting the farms and waterways of this critically important place.1 He began the process by walking around the fields and levees, and making preparatory sketches that he later brought back to the studio. He explains that it felt important to personally experience the landscape in this way before committing it to canvas: “For me, painting has a lot to do with the exercise of empathy, where you have to believe that you’re walking the path or under the trees, that you are somehow able to transfer yourself into that picture.”

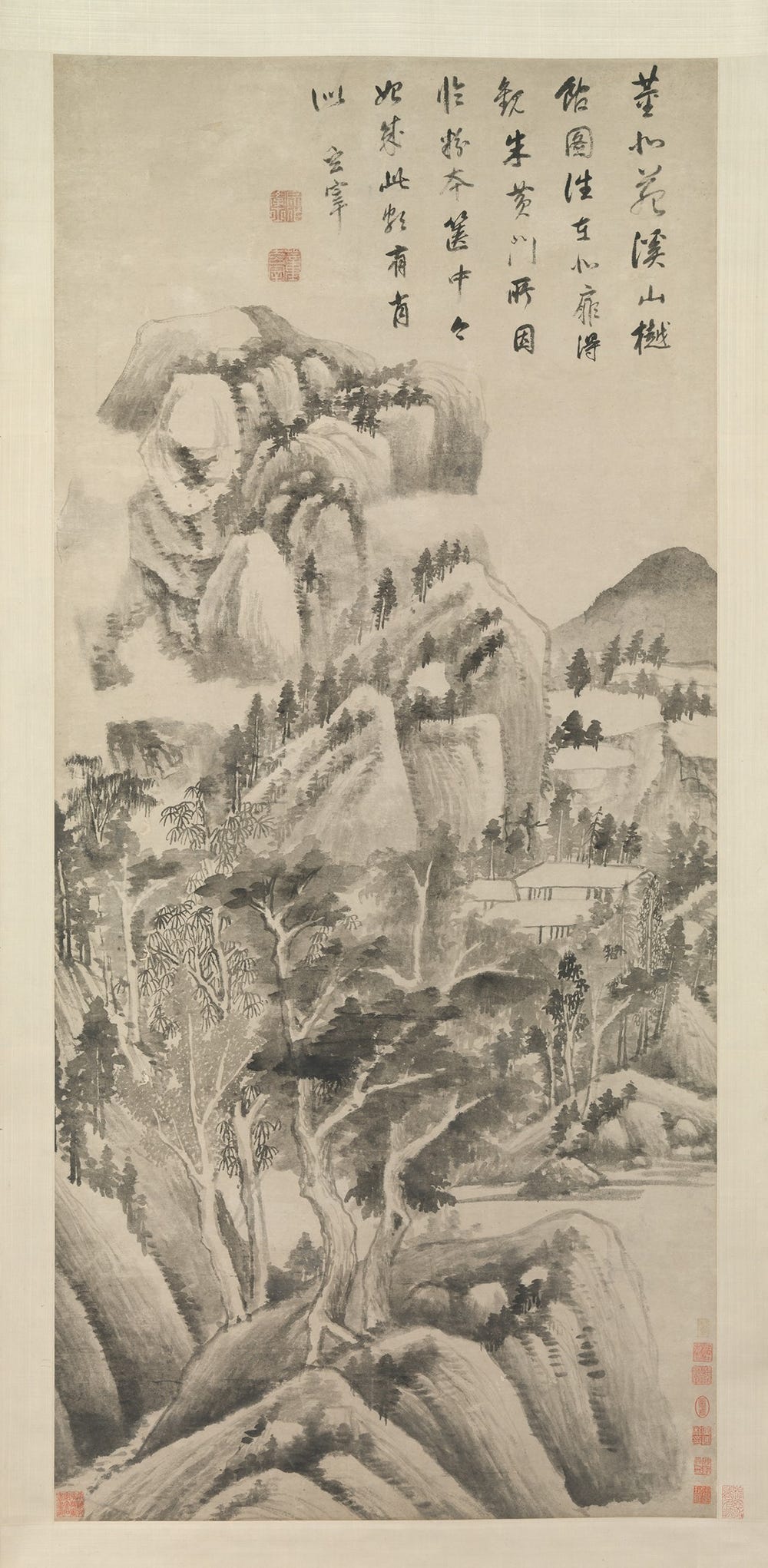

Although the painting’s shifting perspective can feel disorienting, as viewers we can use our imaginations to “transfer ourselves” into the world of Ponds and Streams. We can follow the curves of the canal, look down the furrows of the field, or picture what it would be like to stand in the blue shadows of the trees gazing out over the central retention pond. With its disparities in scale and simultaneous, exhilarating perspectives, the composition recalls Thiebaud’s fondness for Chinese landscape painting. In addition to offering many different views of the same landscape at the same time, Thiebaud also aims “to anthologize or balance” the region’s kaleidoscope of seasonal colors: The browns, blacks, and grays of barren winter coexist with the greens and yellows of early spring.2

Dong Qichang (Chinese, 1555–1636), Shaded Dwellings among Streams and Mountains, ca. 1622–1625 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A dynamic vision of fertile California farmland, Ponds and Streams also inspires viewers to consider more deeply the urgent environmental issues of the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta. Specifically, as the title suggests, Thiebaud’s landscape focuses on the ponds, streams, and waterways that power the region’s highly productive agricultural enterprises. Water is essential to the region’s farms and the communities of people who live and work in these areas, driving the local economy and growing essential crops that feed so many.

Ponds and Streams was gifted to the Fine Arts Museums by Richard and Rhoda Goldman, lifelong environmental advocates and founders of the Goldman Environmental Prize. By looking at Ponds and Streams through the lens of water conservation and environmental sustainability, we can begin to consider the various water resources that shape — and are shaped by — this unique landscape. Thiebaud’s painting provides an opportunity to consider the important work being done to manage water resources in California to ensure that the health of these farms, communities, and environmental systems can endure.

I spoke with two environmental advocates whose organizations are working at the forefront of water conservation and restoration in agricultural regions of California. Julie Rentner, president of the organization River Partners, and Aysha Massell, director of the Water for the Future program at Sustainable Conservation, helped explain how Ponds and Streams can be understood in the context of water-resource management, environmental sustainability, current conservation and restoration projects, groundwater recharge, and the need to reintroduce critical California habitats.

— John Muir, 1875[The] Sacramento Valley is entirely covered with ancient river drift, and I wandered over many square miles of it. In every pebble I could hear the sound of running water. The whole deposit is a poem whose many books and chapters form the geological Vedas of our glorious State. (3)

California’s Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta The Freshwater Trust IBM Research via Flickr, Licensed Under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License

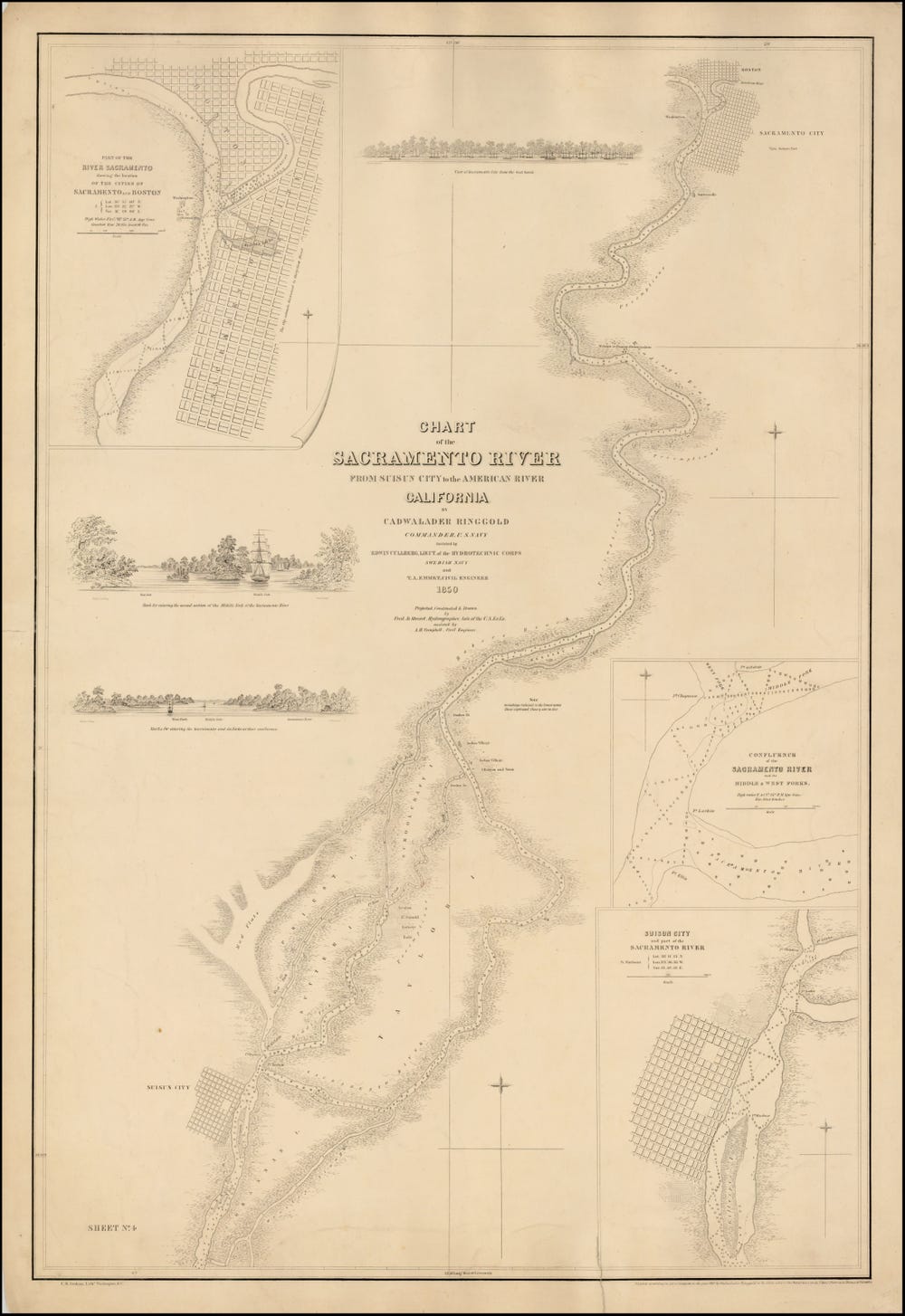

The Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta was once a great tidal freshwater marsh.4 As Massell explains, “The ponds and streams of the Central Valley are alive, but different than they once were. Gone are the meandering streams and vast wetlands that once dominated the landscape and supported great numbers of birds, fish, and elk that in turn supported the Yokut, Miwok, and Maidu people, among many others.” With the Reclamation District Act of 1861, the California Legislature authorized levee construction to make the land more suitable for farming. The region’s marshes were drained, reformed by channels and levees, and converted into fertile farmland. The physical work required by these reclamation and irrigation projects in the “tule lands” of the delta was largely done by Chinese laborers, along with workers from India and Hawaii, who used hand tools to reclaim about 140 square miles of land.5 The soil subsided, and the shallow fields — now below sea level — could be irrigated by flooding.

Cadwalader Ringgold Detail from the Chart of the Sacramento River from Suisun City to the American River, 1850 © Stanford University. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike

Agriculture flourished in the Delta, and the region is now essential to California’s communities and ecology. In addition to providing water to millions of Californians6 and fueling a major agricultural industry (more than 80 percent of the region, or 553,687 acres, is used for farming), the Delta is also home to more than 750 animal and plant species, including many birds and fish that are now listed as threatened or endangered. While farmers and their communities value this land and try to protect water resources, work still needs to be done to recover local wildlife habitats, manage groundwater, and improve water quality for all living things. Massell explains, “Agriculture is an essential part of the way forward — we want to keep it vibrant in the Valley and craft sustainable solutions that support people and the environment.”

River Partners is an organization dedicated to giving life back to rural and agricultural landscapes at the river’s edge. Looking at Ponds and Streams, Rentner notes, “There’s a timeliness in it. I see the landscape as it looks today. As I look at the striping of crop patterns, the road ringing the water feature, or the levees that have been dug out, I see the human footprint on water in the Central Valley . . . the living and vibrant processes of the Central Valley are completely gone. On the flip side, as a part of an organization that wants to see something different, I see a starting place for recovery. Bringing life into the valley, into this painting, is an activity that requires people participating in the rejuvenation of soils that have been depleted, replenishing the life that has been disappeared completely. There’s opportunity to connect to the natural cycles that are muted in the geometry of the painting.”

“There should be flocks of migrating waterfowl, either in the sky or the water. There should be songbirds lining the trees at the water’s edge. There should be fish in all of that water. If you went back to before these canals were dug in the first place, the landscape would be full of deer, elk, and bears — apex predators are missing. It’s only been 150 years since the land looked like this.”

USFWS Pacific Southwest Region via Flickr, Licensed Under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License

Rentner describes how River Partners might implement such environmental solutions in Thiebaud’s landscape, such as regrading the land around the canal at the top of the painting to make a larger wetland. “Dozens of shrubs, trees, and grasses could be planted in that area, where we could rely on the variability of the stream to periodically dry out that triangle of land. That change would provide a variety of houses for all the wildlife activity there — resting, nesting, rearing. If River Partners were engaged in doing a project in this painting, it would be in that triangle, bringing back life to those animals, and bringing back vegetation.”

Rentner continues, “In this landscape, natural processes have been muted or controlled, and giving new life to landscapes like this is simply about a recognition that we’re learning a lot more about our own reliance on ecological processes to keep ourselves and our families healthy. This image is a representation of what we used to think was necessary for economic growth, to manage water in a way that wouldn’t harm people, but what we know now is that we need the landscape to look really different to sustain people in healthy ways and make us more resilient to what is coming down the pipeline. This is the landscape that we work in. We give new life to river landscapes, so we empower people with proven solutions for resilient communities.”

Sustainable Conservation supports collaborative solutions to meet the water needs of California’s environment, people, and economy. Massell frames Ponds and Streams by reminding the viewer that “Everything depends on water, and the earth is drying up. Groundwater is plummeting, snowpack is shrinking, and even the ground beneath our feet is sinking. In our dreams of endless progress and efficient order, we have forgotten the wildness of our origins — but it still emerges mercilessly in drought, fire, and flood.”

Thiebaud’s painting explores the geometric textures of the land as it has been shaped and tamed into plowed furrows, planned orchards, and controlled canal systems. “When I look at this painting, the water is very contained,” Massell says. “The irrigation canal may have once been a river, which in its natural state may have been rather messy, had a lot of meandering curves and vegetation all around it. Rivers tend to form and reform their channels year after year, so they need room. This is a very orderly view of a “disorderly” environment, but that’s California. The Central Valley is volatile and vulnerable in its abundance it is a highly variable landscape upon which we impose human order.”

Wayne Thiebaud, River and Farms, 2002 Art © 2021 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS) / VAGA, New York, NY

Massell contrasts these details with contemporary best practices for environmental sustainability: “We must allow more nature and wildness in our lives . . . we need to give nature more room to be itself. We can farm in between the margins.” In other words, “Instead of the linear, hard edges of our water-delivery systems (so vulnerable to drought and flood), we must give creeks and rivers room and provide migratory pathways through the Valley, connecting coastal ranges and Sierra foothills. We can allow floodwaters to reconnect with their ancient floodplains and sink into the ground to replenish the dwindling aquifers below, all while reducing flood risk for human communities. We must transition to agricultural systems that incorporate biodiversity into their very fabric to help pollinate our flowers, clean our water and air, nourish our people, and keep wildness in our world. The typical intensifying battle of fish versus farms is becoming moot, as the fate of both is inextricably linked. We must move beyond the zero-sum water struggles of the twentieth century as we transition into an era of incredible climatic shifts that will affect us all.”

People have a right to water, and, in many cases, Delta farmworkers and their communities are suffering the consequences of poor water-management practices and exposure to pesticides and other harsh chemicals.

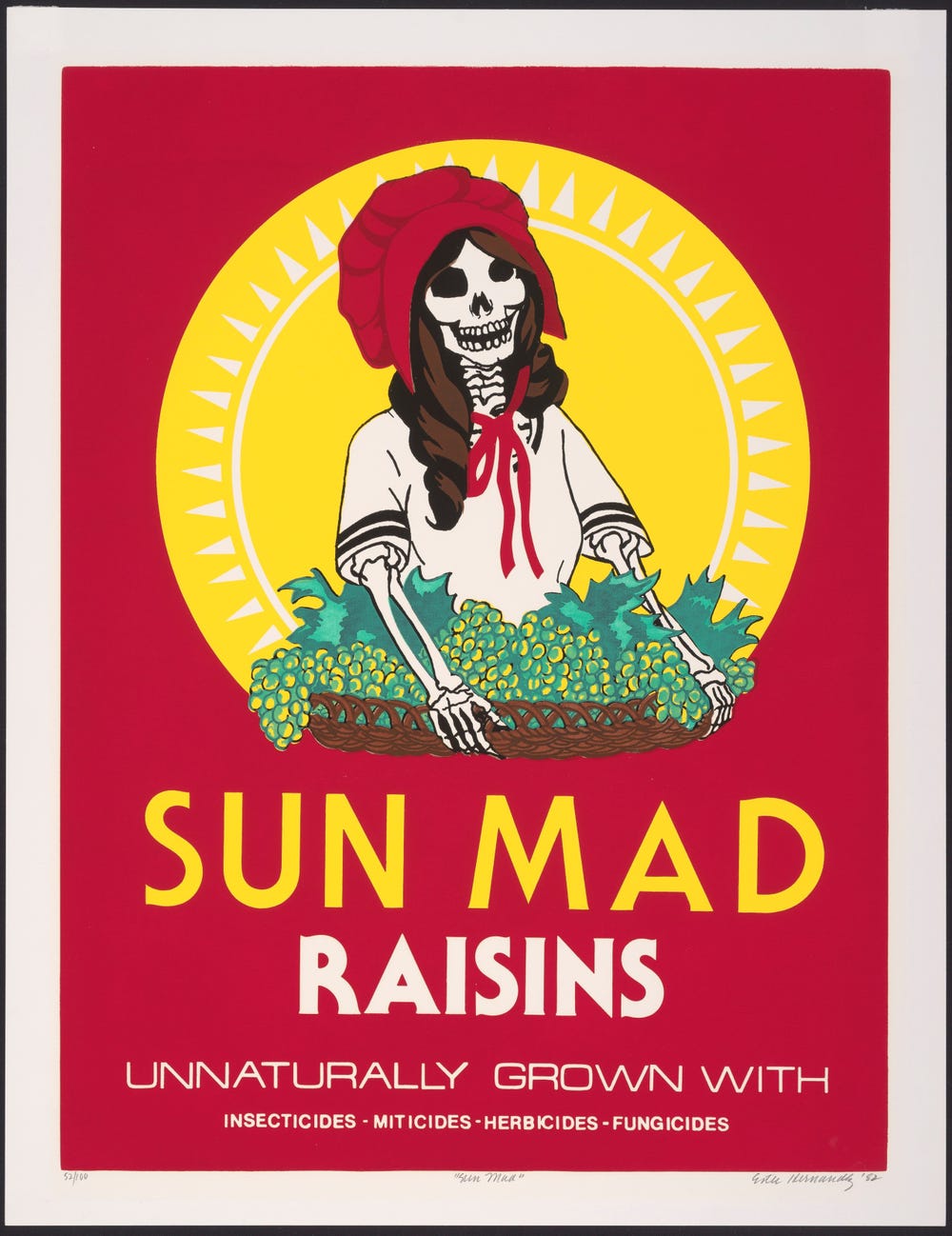

Sun Mad © 1982 Ester Hernandez

While the figures in Thiebaud’s painting are small and few, their labor is apparent throughout the scene, and they are the group most impacted by the degradation of local water quality.

Fortunately, much has changed in the twenty years since Thiebaud painted Ponds and Streams. Today, more people understand the need for urgent change in order to secure our water future. Organizations like River Partners and Sustainable Conservation help steward multi-benefit projects that support water-restoration initiatives and help farmers transition to more resilient agricultural systems. Beyond offering an exhilarating view of the Delta landscape, Ponds and Streams also provides a lens through which we can consider the future of California’s ecology and the actions we can all take to ensure the long-term health of our precious natural resources.

Text by Lauren Palmor, assistant curator, American Art.

Learn more about American art at the de Young

About River Partners

River Partners brings life back to California’s rivers. Founded in 1998, the nonprofit harnesses the power of restored riverways to create a thriving future for the state’s environment and communities. Using modern farming practices and cutting-edge science, River Partners reforests and reconnects entire river landscapes, critical wildlife corridors and networks, and vast ecological regions at a bold pace and scale. The organization’s statewide efforts result in lasting, tangible wins for wildlife, flood safety, climate resiliency, water conservation, public health, and local economies. River Partners has the largest on-the-ground restoration footprint of any nonprofit or firm in the western U.S., having led hundreds of large-scale projects across nearly 17,000 acres throughout California. www.riverpartners.org | info@riverpartners.org

River Partners invites you to join them in bringing life back to California’s iconic, imperiled riverways.

About Sustainable Conservation

Sustainable Conservation helps California thrive by uniting people to solve the toughest challenges facing our land, air, and water. Every day, they bring together business, landowners, communities, and government in some of the most productive yet economically disadvantaged parts of California, to steward the resources on which we all depend in ways that are just and make economic sense.

Sustainable Conservation currently drives collaborative solutions to meet the water needs of California’s environment, people, and economy for current and future generations—with particular focus on advancing sustainable groundwater management and accelerating the stewardship of natural and working lands and waterways. A sustainable water future for California that supports a thriving economy is achievable. But, a future in which nature and people have access to clean, affordable, and reliable water is possible only by working with — not against — each other. https://suscon.org/about-us/

1 Wayne Thiebaud, “So we did — I did lots of river pictures, lots of river landscapes, going out directly and painting. Then we owned a home down below Sacramento, near the delta, for about three and a half years, a big old, dilapidated mansion that we bought — which was a kind of a horror when we bought it — and fixed it up. But it was in the middle of pear orchards, and the river was right in front of the house. Did lots of series of those then.” Susan Larsen, “Oral History Interview with Wayne Thiebaud,” Archives of American Art.

2 Susan Larsen, “Oral History Interview with Wayne Thiebaud,” Archives of American Art.

3 John Muir, Letters to a Friend; Written to Mrs. Ezra S. Carr, 1866 – 1879 (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1915).

4 S. E. Ingebritsen and Marti E. Ikhara, “Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta: The Sinking Heart of the State,” U.S. Geological Survey, Fact Sheet 005 – 00.

5 George Chu, “Chinatowns in the Delta: The Chinese in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, 1870 – 1960.” California Historical Society Quarterly Vol. 49, No. 1 (March 1970), pp. 21 – 37.

6 Two-thirds of California’s population, or more than 20 million people, gets at least some of its drinking water from the Delta (Delta Protection Commission, 1995).