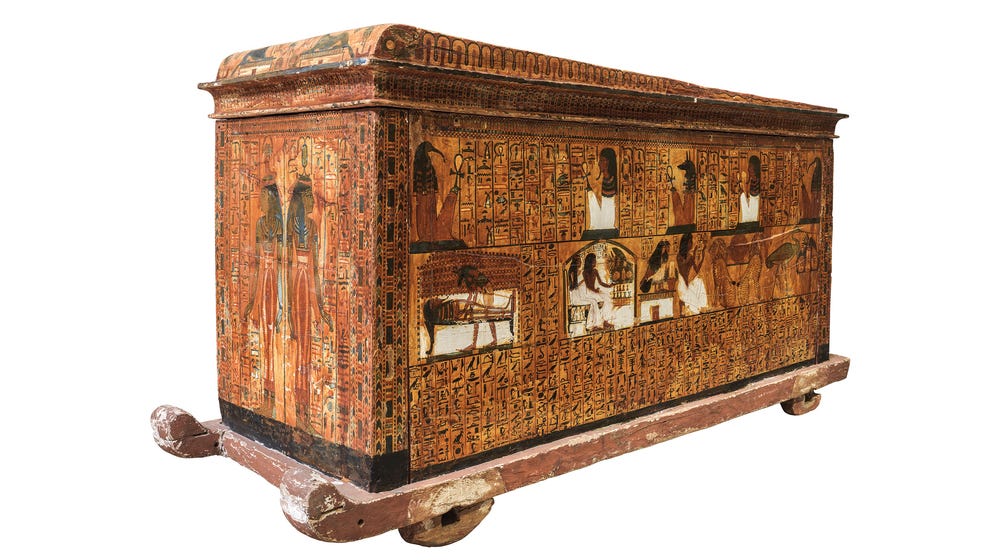

One of the most glorious and revealing galleries in Ramses the Great and the Gold of the Pharaohs is the one that holds a single object. It is the outer coffin of the ancient Egyptian artisan Sennedjem, who lived in Deir el-Medina (in Egyptian, Set Maat or “Place of Truth”) during the reigns of Ramses II and his father, Seti I. He was part of an elite group of skilled craftspeople and artists who lived in this walled village on the west bank of the Nile at Thebes and worked primarily in the tombs in the nearby Valley of the Kings. Sennedjem held the title of “servant in the Place of Truth,” indicating that he was one of a team responsible for constructing and decorating the royal tombs. Sennedjem’s own tomb was on a hill overlooking the workers’ settlement. A small pyramid sits on top of the entrance to an offering chapel. Below that lies Sennedjem’s decorated burial chamber. The painted reliefs from the walls and ceiling of that chamber are reproduced in the exhibition and surround Sennedjem’s coffin, as they did when the intact tomb was discovered in 1886. These are some of the most famous scenes from Egyptian tombs and show his progress from death into the afterlife.

The wooden coffin is beautifully decorated in vivid colors with texts and vignettes from the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Many extraordinary painted scenes on the coffin also appear on the tomb’s walls. For example, Sennedjem’s mummy lying on a lion-shaped bed attended to by Anubis, the god of death and mummification, is also on the north wall of the tomb. Sennedjem and his wife, lyneferti, playing the board game senet in front of a table of offerings on the coffin was also placed at the entrance to the burial chamber. The game was associated with the journey to the afterlife, and some squares reveal the hazards a person might meet on this cosmic journey. Others are good places to land as you travel this route.

Sennedjem’s village of Deir el-Medina was a department of the government and, as such, was supported by taxes of food and supplies levied on the area of Thebes and drawn, in monthly rations, from the nearby royal mortuary temples. It was the community of a permanent workforce and their families for about 400 years. Starting in the early 18th Dynasty in the late 16th century BC, this remarkable community was abandoned during the reign of Ramses XI in the 11th century BC when looting of the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings became widespread.

Thanks to the degree of literacy in this crowded village with about 70 houses within the walls and 50 beyond, there are preserved documents written on papyri, broken bits of pottery, and flakes of limestone that reveal the workers’ day-to-day lives. Thanks to these records, we know how their work was apportioned and carried out. The documents describe how the workers were divided into two groups, right and left, which may indicate that the two sides of a tomb were worked on simultaneously, each with a foreman in charge. A “scribe of the tomb” kept a daily progress record and attendance register. The men worked eight hours with a break in the middle and a day off every 10 days. While working on the tombs, the workers had cooked meals delivered to them from the village. Money did not exist in ancient Egypt, and the workers were paid with rations of grain, augmented by fish, vegetables, wood for fuel, pottery, and occasionally treats of meat, wine, and beer. In today’s terms, they would be considered middle-class. During their days off, they could work on their own tombs; in Sennedjem’s case, his is regarded as one of the most beautiful constructed for a nonroyal.

Text by Renée Dreyfus, George and Judy Marcus Distinguished Curator and curator in charge, ancient art. Adapted from Fine Arts, Fall 2022.

Ramses the Great and the Gold of the Pharaohs is on view at the de Young from August 20, 2022 through February 12, 2023.