John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), El Jaleo (detail), 1882. Oil on canvas, 91 5/16 x 137 in. (232 x 348 cm). Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, P7s1

John Singer Sargent (1856 – 1925) likely first encountered flamenco during an extended trip to Spain in 1879. Pioneered by the Roma inhabitants of Andalusia in Southern Spain, flamenco is made up of three main parts: el cante (song), el baile (dance), and el toque (guitar playing). This rhythmic art form inspired some of Sargent’s greatest works. While Sargent — himself a skilled pianist, as well as a guitarist and banjo player — was interested in a wide range of musical traditions, he was particularly passionate about flamenco.

Emilio Beauchy (1847–1928), Sevilla: Café Cantante, ca. 1880. Albumen silver print, 8 3/5 x 11 1/10 in (21.8 × 28.1 cm). Moderna Museet, Donation 1968 from Gunilla Hammarsjö, FM 1968 003 018

With centuries-old roots in Spanish Roma culture, flamenco began as a predominantly improvisational art, traditionally performed in a domestic setting for family and friends. During the mid-late 1800s, these intimate and informal performances became professionalized and available to a wider public in what were known as cafés cantantes. These lively “singing cafes” typically featured a raised stage where performances would take place as patrons ate and drank at tables below. Then, as now, audience members customarily shouted out jaleos, or expressions of praise and encouragement, accompanied by palmas (handclaps) and pitos (finger snaps).

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Spanish Roma Dancer, ca. 1879–1880. Oil on canvas, 18 ⅛ x 10 ⅞ in. (46 x 27.6 cm). Private collection. Image courtesy Adelson Galleries, New York

One common jaleo, the expression olé, appears in the background of Sargent’s Spanish Roma Dancer (ca. 1879 – 80). The painting is one of two closely related portraits Sargent made of an unidentified flamenco performer, whom he may have seen during his 1879 trip to Spain. Although it is possible he created the portrait in his Paris studio, the lively, sketchy brushstrokes used for the subject’s fringed shawl imbue the portrayal with a sense of dynamism and spontaneity.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), El Jaleo, 1882. Oil on canvas, 91 5/16 x 137 in. (232 x 348 cm). Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, P7s1

Sargent’s tour-de-force portrayal of a flamenco performance, El Jaleo (1882), captures the intensity of feeling associated with this celebrated art form. The word olé is scrawled on the wall at right, emphasizing the sensory richness of the experience presented. In El Jaleo, Sargent created the illusion that we are witnessing a real performance, thrusting us into the scene with a sense of urgency and immediacy. Yet Sargent’s process of creating El Jaleo was anything but spontaneous. He completed the painting in his Paris studio, more than two years after his 1879 trip to Spain. To produce this carefully crafted fiction, he relied on both his memories of the performances he had seen in Spain and numerous detailed studies he made, often working from posed models.

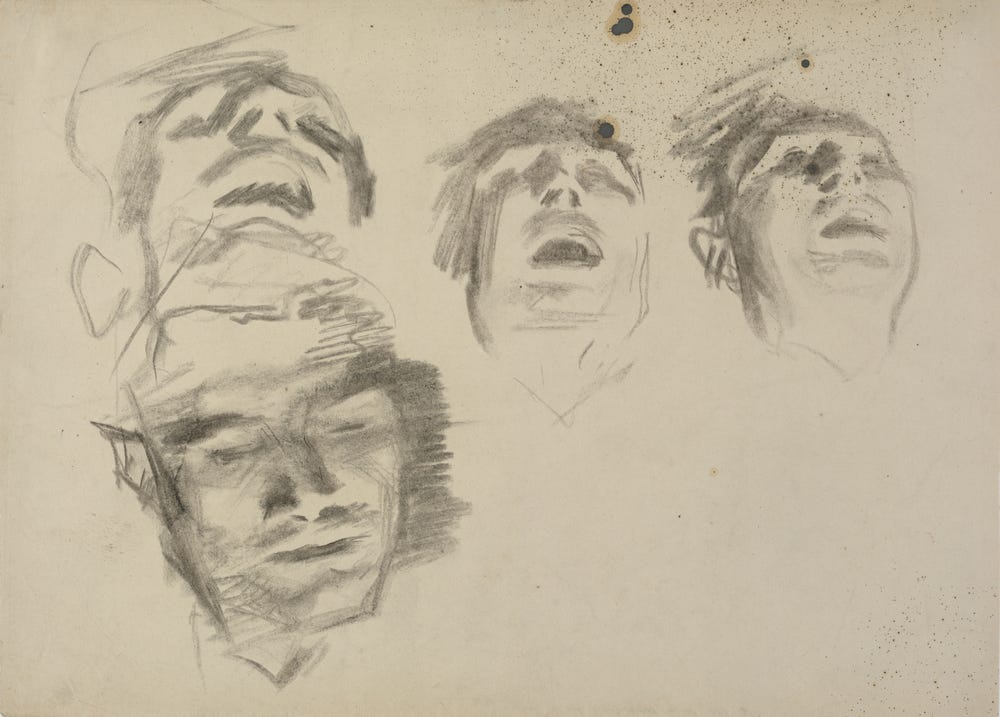

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925). Study for “El Jaleo”: Seated Musicians’ Faces, 1881. Charcoal on paper, 9 5/16 × 13 in. (23.65 × 33.02 cm). Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

El Jaleo caused a sensation at the 1882 Paris Salon, a reflection of both the artistic merits of the painting and the popularity of its subject at the time. This was a moment when the frenzy for all things Spanish was at a peak in both Europe and America. This vogue both shaped and reflected Spain’s burgeoning tourism industry, as well as the market for romanticized and exoticized scenes of Spanish life by Sargent’s contemporaries, such as William Merritt Chase and the popular Spanish artist Marià Fortuny.

Sargent shared his love of flamenco with his friend and patron Isabella Stewart Gardner, gifting her records of his favorite musicians. Gardner had long admired El Jaleo and acquired the painting in 1914 from Thomas Jefferson Coolidge, her cousin through marriage. For over a century, El Jaleo has occupied pride of place in the arched alcove Gardner designed for the painting in the “Spanish Cloister” of her Boston home, now the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. For generations of viewers, El Jaleo has come to epitomize flamenco dance and music.

The appeal of flamenco for American audiences is clear from the variety of companies specializing in this dance tradition established throughout the United States, many of them in Northern California. The Bay Area has long been a creative center for flamenco performance. During the 1950s, at the height of the Beat era, flamenco dancers, singers, and guitarists joined the bohemian artists, poets, and jazz musicians who congregated in San Francisco’s North Beach to express themselves in a creative, socially nonconformist atmosphere. The incredible talent and diversity of San Francisco’s flamenco community was on display at “Las Cuevas de los Flamencos,” a performance space in the Old Spaghetti Factory (in operation 1955 – 1984) at 478 Green Street, where jam sessions often took place.

Dancing in the courtyard of the Old Spaghetti Factory: Ernesto Hernandez (left), David Jones (a.k.a. David Serva, center), Isa Mura (right), and unknown guitarists.

Celebrated flamenco dancers flocked to the Bay Area, including Cruz Luna, who performed on Broadway and established the Casa Madrid in North Beach in 1960; Adela Clara, who founded the Theatre Flamenco company in 1966; Rosa Montoya, who created the Bailes Flamencos dance company in 1975; and singer Isa Mura, whose daughter, Yaelisa Petlin, founded Caminos Flamencos in 1993. Reminiscing about her childhood exposure to flamenco in the Bay Area, Petlin recalled:

The Spaghetti Factory was a grounding and centralized location where all new, and upcoming, and more seasoned performers could get together every weekend and learn and grow. And other Flamencos came into town. We were visited by lots of flamenco artists from Spain that came through and saw the great love that was being created in North Beach, and in San Francisco, and the Bay Area for Flamenco, and they wanted to be a part of it. This is how I grew up around the local flamencos, including my mother and then the visiting artists. . . . It’s always important to have these very authentic and wonderful artists come through an area, and this is how Flamenco grows and develops.

Yaelisa Petlin, interviewed by Frances Homan Jue, December 2, 2022

Today, San Francisco continues to be home to festivals, schools, and performance collectives, such as the San Francisco Flamenco Dance Company. Founded in 2004, the Bay Area Flamenco Festival has showcased Spain’s greatest flamenco artists on a nearly annual basis.

The enduring resonance of this centuries-old art form lies in its authenticity, visceral strength, and power. Describing the state of duende — an intense, deeply emotional and almost trancelike experience that can absorb a performer in flow — the Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca (1898 – 1936) observed:

So, then, the duende is a force not a labour, a struggle not a thought. . . . Seeking the duende, there is neither map nor discipline. We only know it burns the blood like powdered glass, that it exhausts, rejects all the sweet geometry we understand, [and] that it shatters styles.

Federico García Lorca, “Theory and Play of the Duende,” 1933

Text by Emma Acker, associate curator, American art.