Carol Queen, PhD, is a San Francisco sexologist and sociologist whose special interest is sexuality and culture. She was invited to comment on the Legion of Honor’s exhibition Last Supper in Pompeii, showcasing artifacts, especially those that document drinking and dining, from the legendary city destroyed by Mt. Vesuvius in 79 CE. Here are her reflections, via the mirror of her years in the Bay Area.

“Naughty” Art Content Advisory: This article contains sexually explicit content that may not be suitable for all viewers.

Installation of Last Summer in Pompeii, at the Legion of Honor. Photography by Gary Sexton.

In the accompanying publication for Last Supper in Pompeii, scholar Paul Roberts writes about the vital food and wine culture of ancient Pompeii and imagines the doomed Lady of Oplontis, one of the countless victims of the catastrophic Mt. Vesuvius eruption. Roberts acknowledges the end-of-life rituals the Lady could not receive, since her demise was so sudden: “We must imagine for her a journey’s end that she would have wished . . . drinking and feasting into eternity.”

That does seem a lovely endnote to a life, and I’m sure many of us might wish it for ourselves. Perhaps it’s even why we settled in the beautiful Bay Area in the first place—to have that sense of living well—and well-fed. But I am a sexologist as well as a devoted San Francisco transplant, and I cannot help seeing other profound parallels between the life I’ve lived here and the one they lived long ago in Pompeii.

I spend part of every week in Napa, on the other side of Mt. Atlas. That hilly escarpment is no volcano—but when the Atlas Fire sparked there on a windy October night in 2017, everyone in the immediate region had to flee as surely as if pyroclastic flows were coming down its slopes. Fire danced menacingly through the trees, pursuing my partner as he drove away.

The ruins of the Temple of Apollo, Pompeii. Roberto Lo Savio / EyeEm / Getty Images

The rest of the week, I live in a rent-controlled San Francisco flat. I had just moved to the city in 1989 when the Loma Prieta quake shook us hard enough to make bridges crack and overpasses fall. Almost two millennia before, a Big One hit Pompeii, too, cracking and tumbling buildings, but people in seismic country live on the edge and make the best of the years between the shakes—I bet that was as true for the Pompeiians as it is for us. Maybe the good life is sweeter when you know in the back of your mind you could be at risk.

I guess we’re all fortunate in that the nearest volcanoes are far across the state, but we Bay Area folk don’t live in a quiet place. I came to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1985, and for at least the next twenty years I felt that I was living in the shadow of a volcano of a different kind. In those years, HIV/AIDS burned through this region like a fire that couldn’t be extinguished. You have to look a little harder to see evidence of that disaster now, though signs of a more contemporary pandemic are still all around us. Even so, the minute people could leave their Covid-quarantine homes and pull down their masks at brunch, there they were: long lines of them at wine-country venues and taking over the whole street near my home in Hayes Valley.

Fresco of a Satyr and Maenad in an Intimate Embrace. National Archeological Museum of Naples. Photograph by Gary Sexton

People were so shocked in the eighteenth century when the archaeological digs began in Herculaneum and Pompeii—not by the culture of food and wine, but the sex! The sexy murals in the brothels, and the places that on second thought maybe weren’t brothels but were decorated with sexy frescoes anyway. The stupendous phalluses on the “fertility” statues in the garden, like Priapus—a minor god always depicted with huge penis flying high—was some sort of frisky gnome. Soon enough it was all hidden away in the Naples Archaeological Museum—locked in a so-called Secret Cabinet (Gabinetto Segreto) only accessible to a few. No upright families should get the idea that it was okay to decorate like that, visit such places, worship the likes of Bacchus and Venus. But you can’t keep a good god of pleasure nor goddess of love down! The sexuality of antiquity has been intriguing, calling, sometimes even guiding, subcultures ever since the digging and excavating began. What was the Summer of Love but all those old deities rising?

Fresco of Mercury/Priapus. National Archeological Museum of Naples. Photography by Carole Raddato

I wonder what future archaeologists, two thousand years from now, will think of our leftover cultural detritus. As a socially responsible hoarder (that’s archivist, when I’m talking to academics), I’ve helped preserve all I could of the recent history of the sexy town we live in now. They say history is written by the victors, but it isn’t written at all, if no one finds the clues you left behind.

The organization I cofounded with my partner, Robert Morgan Lawrence, the Center for Sex & Culture (CSC) held onto a triptych of paintings depicting shenanigans at a 1970s Hooker’s Ball. CSC showed a collection of more than 70 safe sex posters collected by gay activist Buzz Bense. A drawing club used the space at CSC to sketch models hanging from the ceiling in suspension bondage. Memorial gatherings were held for (to name just a few) porn greats Candida Royalle, Juliet Anderson, John Leslie, and Jamie Gillis; photographer Charles Gatewood; and sexologist Rev. Dr. Ted McIlvenna, who walked the streets of the Tenderloin in the 1960s on behalf of Glide Memorial Church, ministering to the sex workers and trans women who rose up in protest at the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot. CSC hosted an art show featuring enlarged Polaroids taken inside a friendly little Western Addition bathhouse called the Fairoaks, frequented by a diverse crowd of men at the height of the 1970s gay revolution. We hosted another show of Cockettes memorabilia, those high-kicking dance hall “girls” with glitter in their beards. The great disco-era musician Sylvester was a Cockette!

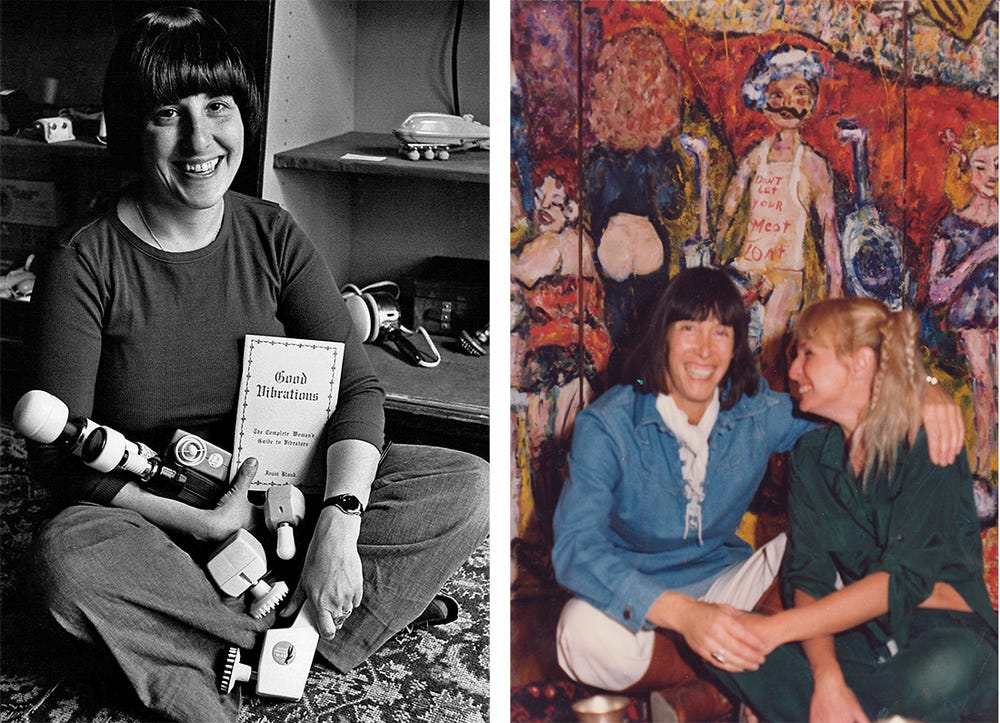

And the many ways San Francisco holds interest for a sexologist like me go much further back than the Summer of Love. In San Francisco’s early years more women were prostitutes than were not. Madams like Belle Cora and Ah Toy ran notable houses. Men up at the gold fields and down in the city slow-danced together. In 1917, angry prostitutes marched on a church whose pastor had been agitating against them. Madam Sally Stanford’s brothel was a few doors down from the hall on Pine Street where the United Nations was founded in 1945. Allen Ginsberg read Howl to the stunned crowd at the Six Gallery in 1955. Margo St. James founded COYOTE in 1972. Joani Blank revolutionized the world of sex toys when she founded Good Vibrations in 1977. The GLBT Historical Society collects materials from San Francisco’s important queer community. That’s just a smidgen of our often-hidden history. Whether or not it was inspired by Pompeii, this town has been full of sex from the get-go!

L: Joani Blank, founder of Good Vibrations. Photo courtesy Good Vibrations; R: Margo St. James and Roslyn Benet. Photo courtesy Center for Sex & Culture

And, as in Pompeii, class, color, and social status affect the history we know. Most of those stories feature white people. Less is known about workers and the servant and slave class. History favors the people who create or stand atop society and culture—but those who tended the vineyards and kept the brothels busy were (and are) here, and they matter.

Wall painting of a dinner party, 40-79 CE. National Archeological Museum of Naples. Photography by Gary Sexton

People who came to San Francisco might not have been born and raised under a volcano, or in earthquake or fire country. But people came to San Francisco who had lived the slow burn of discrimination or censure. Once we made our way here, out to the edge of the continent, many of us built lives and communities around sexuality—well, and brunch—raising glasses to freedom and the city where we found it. Here we put down our roots—at least until Mother Earth once again shakes us to the ground, as she did to the good people making the wine and raising their glasses in our long-ago sister city, Pompeii.

Carol Queen, PhD, is the cofounder and director of the Center for Sex & Culture and staff sexologist at Good Vibrations. Like the musician Eric Burdon of the Animals, she says of San Francisco, “I wasn’t born here . . . perhaps I’ll die here; there’s no place left to go . . .”

Learn more about Last Supper in Pompeii, on view now at the Legion of Honor through August 29, 2021.