To quote the English writer E.M. Forster, the story of the LGBTQIA+ community is “a great unrecorded History.” Largely erased, remnants survive in meaningful glances, rare documents, and powerful visual testimonies that the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco treasure, preserve, and celebrate as part of a common history. While great progress has been made in the last few decades—most significantly with the gay-liberation movement, the legalization of marriage between same-sex partners in many countries, and the prosecution of hate crimes—up until very recent times relationships between two people of the same sex was (and, in many countries, still is) considered illegal.

In celebration of this year’s Pride Month, we would like to share a selection of works from the Museums’ collection that shed light on private moments of male same-sex intimacy. While justly normalized today, such depictions of tender acts were incredibly radical at the time of their conception and charged with powerful political meanings of love, freedom, and pride.

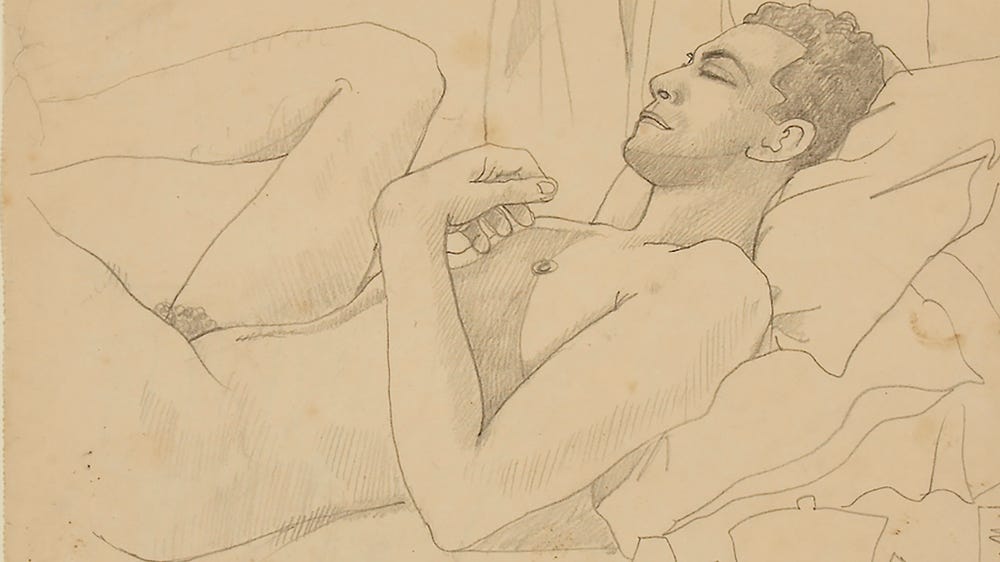

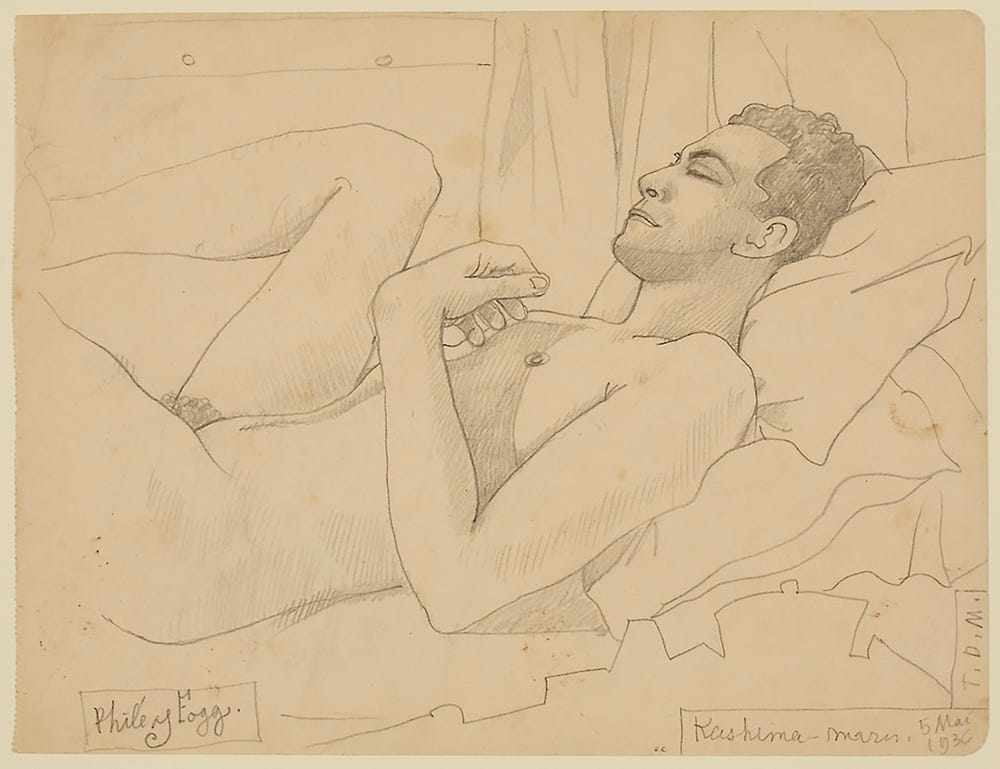

Jean Cocteau, “Lover Asleep” (1936)

A towering figure of the Dada and Surrealist movements of the twentieth century, Jean Cocteau (1889–1963) was hugely influential for European avant-gardes, thanks to an impressive body of work that included poems, films, paintings, decorative arts, set designs, and art criticism. While his work as a draftsman is somewhat lesser known, it is incredibly relevant to understanding Cocteau’s epic life and the making of his mythic character.

Jean Cocteau, Lover Asleep, 1936. Graphite on paper, 15 3/8 x 18 1/8 in. (39 x 46 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Joseph F. McCrindle, 2009.21.1 © 2021 Jean Cocteau / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The drawing (above), donated in 2009 by Joseph F. McCrindle, is dated 5 May 1936 and was executed when Cocteau was writing his travel memoir Mon Premier Voyage (Tour du Monde en 80 jours) (1937), an homage to Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days (1872). In an attempt to retrace and emulate the legendary journey of Verne’s hero Phileas Fogg—whose name appears at lower left in the drawing—Cocteau travelled from Athens to Bombay, Rangoon, and New York, accompanied by his lover, the Algerian Marcel Khill (1912–1940).

Identified here for the first time, Khill is portrayed in this drawing by Cocteau in the Kashmir region while resting, sensually reclined, and naked in bed, with his legs open. He is exalted as a symbol of youth and beauty. Cocteau captured his lover’s intimate moments throughout their journey in India (here he is again, in Rangoon, a few days earlier on 22 April 1936). (Khill was later killed in 1940 during WWII.)

Executed by Cocteau by means of neat black-chalk outlines, this striking drawing announces the powerful series produced later by the artist to illustrate his friend Jean Genet’s novel Querelle de Brest, published in 1947, which the German film director Rainer Werner Fassbinder would ultimately translate into the 1982 arthouse queer classic.

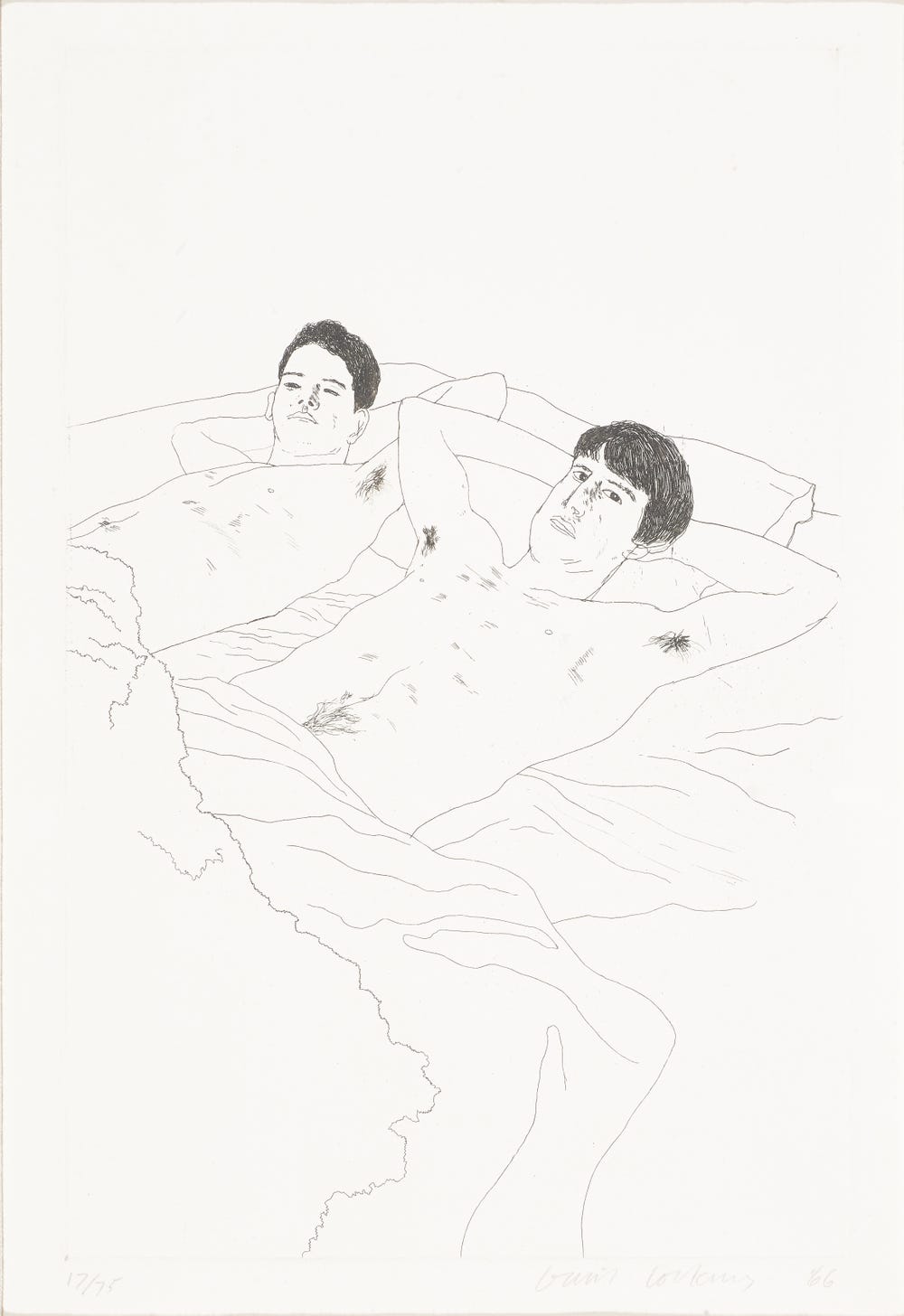

David Hockney, “In Despair” (from the series Fourteen Poems from C.P. Cavafy) (1966)

Produced in a context very similar to Cocteau’s, this newly acquired etching was executed by David Hockney after his travels in 1963 to Alexandria and Beirut. Part of a suite of thirteen prints, this work was intended as a commentary and illustration of poems by the prewar Greek-Egyptian author Constantine P. Cavafy (1863–1933). The young Hockney knew Cavafy’s work since his days at the Royal College of Art in London, and he responded strongly to the poet’s Mediterranean imagery, infused with barely concealed same-sex attractions and unapologetic evocations of homosexual desire. When Hockney was asked to make a series of etchings relating to Cavafy in 1966, he agreed without hesitation and chose only poems pertaining to the author’s upbringing in Alexandria.

David Hockney, In Despair, from the series: Illustrations for Fourteen Poems from C.P. Cavafy, 1966. Publisher: Editions Alecto. Etching, 14 3/16 x 9 1/16 in. (36 x 23 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Anonymous gift in honor of Dr. Stephen O. Murray, 2020.31

Showing intimate sexual scenes between men, his etchings for the series are executed with a delicate linear manner and reflect some of the artist’s most accomplished line drawings to date. In order to make careful pen-and-ink drawings of daily life in Egypt, Hockney spent two weeks in Beirut, which he saw as the contemporary equivalent of Cavafy’s Alexandria, but also he drew upon his own experiences as a gay man in his own environment. For instance, In Despair was most likely drawn in London using two of his friends as models. The suite of etchings was created upon his return to London, and with its realism marked a crucial departure from the artist’s early abstract beginnings. The publication of the etchings in 1966 must also be seen in response to a growing gay-rights movement in the UK, which resulted in the partial decriminalization of homosexuality with the Sexual Offenses Act of 1967.

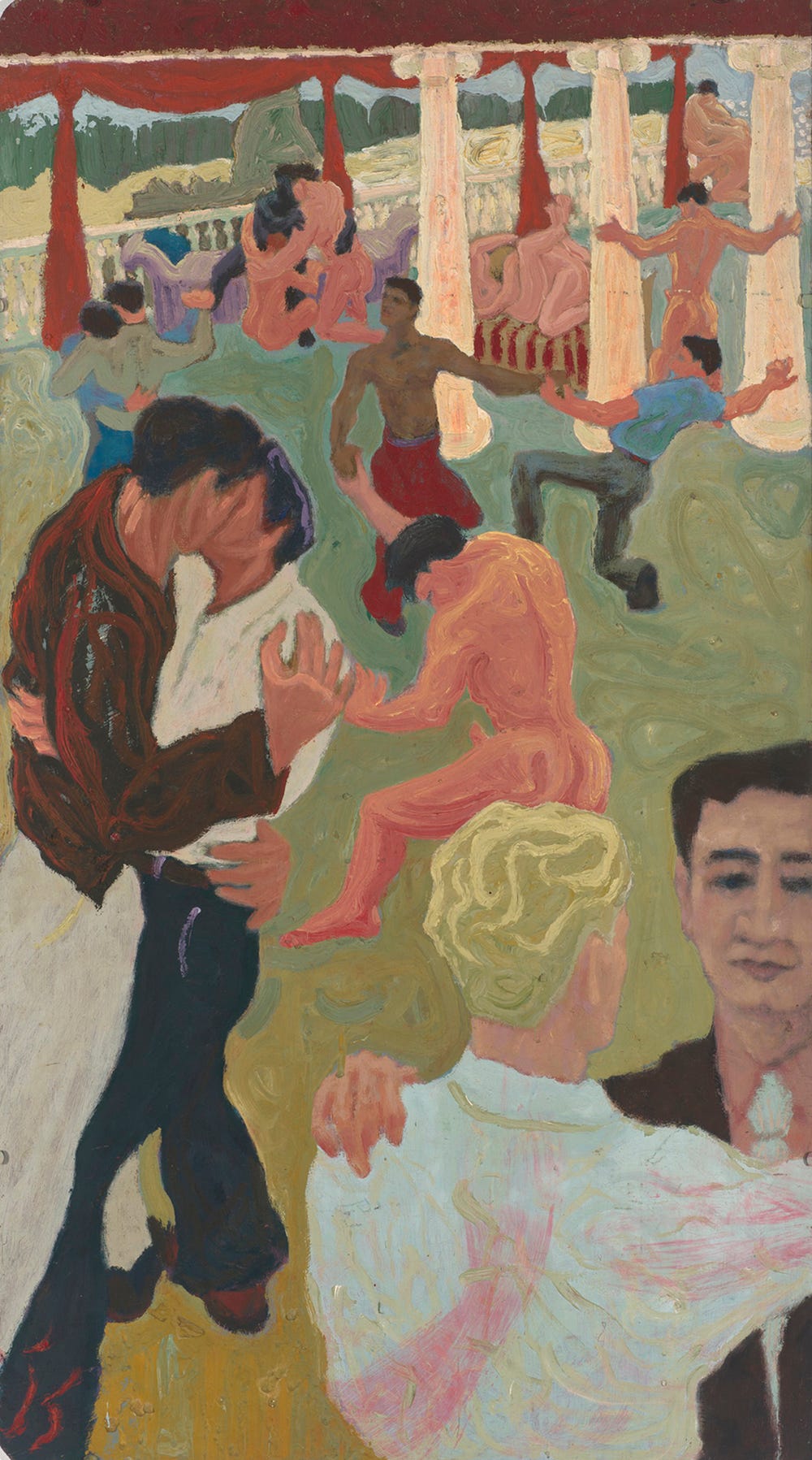

Jess, “Boy Party” (1954)

Announcing an important decade of social battles and cultural shifts in the United States, Jess's lively and liberating Boy Party (1954) constitutes a powerful early record of the life of the queer community in 1950s San Francisco.

Jess, Boy Party, 1954. Oil on plywood, 56 x 32 in. (142.2 x 81.3 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Odyssia Skouras, 1998.6. Copyright The Jess Collins Trust, courtesy Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

After being drafted into the military, the American artist, born Burgess Collins (1923–2004), enrolled in the California School of the Arts. He broke with his family and started referring to himself simply as “Jess.” Together with his partner, the American poet Robert Duncan (1919–1988), Jess became a key member of the 1950s Beat scene and San Francisco’s counterculture community.

As early as 1952, Jess wrote that he had been trying to create “homoerotic romances” with his paintings. An early work, Boy Party captures a moment of such romance and liberation. Set in an enchanted backyard garden, the scene is populated by a diverse community of couples kissing and dancing in the forefront, while others are engaged in more explicit activities in the background. Jess translated on canvas this energetic communal time with vigorous brushwork, an exuberant painterly technique, and flamboyant colors.

Jess’s powerful message still resonates today, as attested by work of the San Francisco–based African American artist John Bankston who, in 2005, paid homage to him in his large canvas Music. Bankston shifted the action from Jess’s protected backyard to an open landscape, projecting the same spirit of homoerotic freedom and sexual liberation into a wider, uncloseted realm.

John Bankston, Music (after Jess), 2005. Oil on canvas, 72 x 96 in. (182.9 x 243.8 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum Purchase, Annenberg Foundation Endowment Fund for Connections Projects, 2006.72.1 © John Bankston, Courtesy of Rena Bransten Gallery

Martin Wong, Sweet ‘Enuff (1988)

As in the works by Jess and Bankston, Martin Wong’s 1988 seminal painting, Sweet ‘Enuff, shifts the queer action and imagery from the intimate/inside to the outside. Populated by firemen, a man hunched over his boom box, and three skateboarders suspended in the air, this large canvas offers a vivid glimpse of the gritty and glamorous Lower East Side scene of the 1980s, as well as a sample of Wong’s powerful pictorial style.

Nurtured by San Francisco’s magnetic counterculture scene of the 1960s and 1970s, in 1978 the Chinese-American artist moved to New York. Seeking inspiration among the overlooked, Wong’s style drew from both the graffiti aesthetic of New York City (his personal collection of works by graffiti artists was extensive) and the Nuyorican and Hispanic artistic scenes—he was romantically involved with the playwright and actor Miguel Piñero, founder of the Nuyorican Poets Café. While a large part of his career happened in New York, Wong was a central figure in the local San Francisco artistic scene, having founded the the queer theater/performance troupe Angels of Light.

Martin Wong, Sweet ‘Enuff, 1988. Oil on canvas and muslin, 69 3/4 x 64 5/8 in. (177.2 x 164.1 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Michael and Judy Moe, 2007.103a-b. Courtesy of the Estate of Martin Wong and P·P·O·W, New York

Text by Furio Rinaldi, curator, Achenbach Foundation for Graphics Arts, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Learn more about the Achenbach Foundation.