On My Illustrated Books

By Enrique Chagoya

November 18, 2021

Since moving to the Bay Area from Mexico City in 1979, I began to have a different perspective of the world and the history of the Americas. This was due to the culture shock I experienced during my first years of living in this country. Attending college here and being acquainted with the local Chicano and Latino community solidified my new views, which were shaped by the physical distance from my formative years in Mexico and my slow adaptation and eventual citizenship to this country. This experience has been perhaps best expressed in making my painted codices (books made in an accordion format, following the ancient style of books from Mesoamerica), which I first started making in 1992 for the five-hundredth anniversary (or quincentenary) of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. Since that first book, Tales of the Conquest (1992), I have finished about forty painted codices and roughly thirty limited-edition print books. Many are now in the public collections of such institutions as the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and Museum of Modern Art, New York.

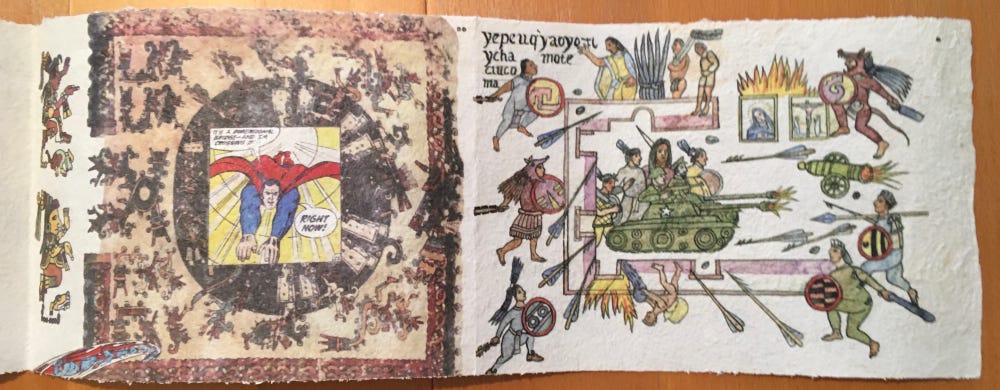

Enrique Chagoya, Tales From the Conquest/Historias de la conquista, 1992. Hand painting on handmade amate paper on solvent transfers of collaged photocopies, .5 in. x 112 in. Collection SFMoMA. © Enrique Chagoya, Image courtesy of the artist

The ancient codices of Mesoamerica and their tragic destruction is something I have had on my mind since I began studying pre-Columbian cultures many years ago. To summarize briefly, a little over half a millennium ago the end of the world came for all Indigenous cultures and civilizations in the Americas when Columbus arrived—in a land that, for the Europeans, eventually became clear as a new continent. The encounter has shaped life in all the Western (and non-Western) world beyond anyone’s imagination, for better or worse.

Enrique Chagoya, Tales From the Conquest/Historias de la conquista, 1992 (detail of pages 1-2). Hand painting on handmade amate paper on solvent transfers of collaged photocopies, .5 in. x 112 in. Collection SFMoMA. © Enrique Chagoya, Image courtesy of the artist

The bloody takeover of the Aztec kingdom during the conquest war of 1519 to 1521 consolidated the Spanish conquest of Mexico and eventually the rest of the continent. This year marks the quincentenary of that holocaust. Particularly cruel was the destruction of the Aztec library of Texcoco, most likely the largest library in the ancient Americas, built by Nezahualcoyotl (a poet and architect king who opposed human sacrifice during the peak of the Aztec empire). The Catholic priests, not knowing the contents of the books, considered them as devil worshipping and obstacles to Christianization. The library and its destruction were best described by a noble Aztec who survived the conquest, Fernando de Alva Ixtlixóchitl. (Ixtlixóchitl is known for his own book, the Codex Ixtlixóchitl, from which I have borrowed some imagery.) According to Miguel León-Portilla, a historian of pre-Columbian culture who corroborated Ixtlixóchitl’s account with different sources, there was a mass suicide when the population of Tenochtitlán (present-day Mexico City) witnessed the burning of the books from that library, and neither the priests nor the soldiers were able to stop it.

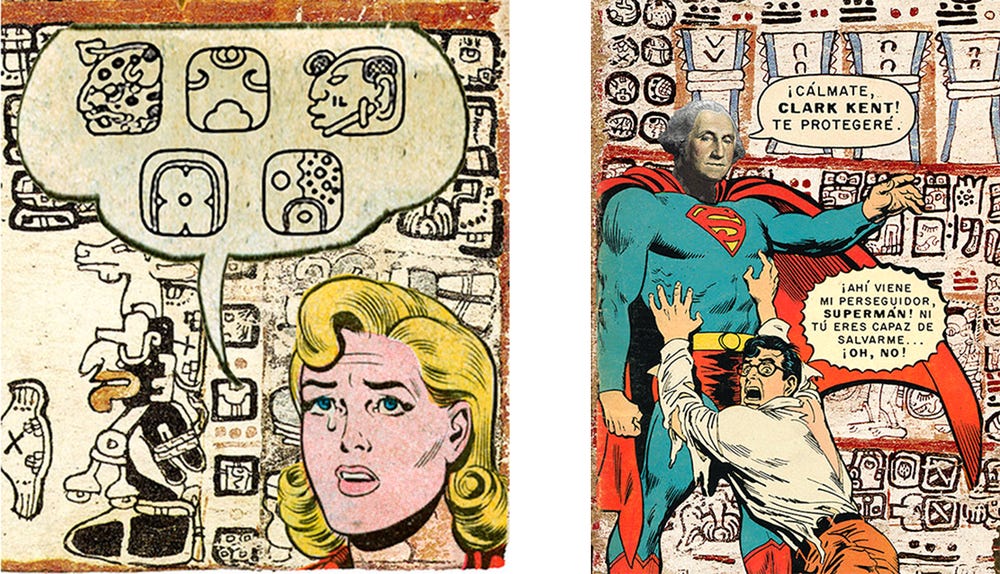

Enrique Chagoya, El Popol Vuh de la Abuelita del Ahuizote/The Community Book of King Ahuizote's Granny, 2021. Digital cured acrylic print on handmade amate paper, 8.5 in. x94 in. Published by Magnolia Editions in Oakland, limited edition of 12. © Enrique Chagoya, Image courtesy of the artist

The remains of pre-Columbian objects and monuments are the only sources of information we have to get a sense of the lost world. Mesoamerican codices from central Mexico and parts of Central America are probably the rarest objects to provide such information. Today only four Mayan pre-Hispanic books, three in Europe and one in Mexico, and around nineteen Mixtec-Zapotec codices remain. No pre-Hispanic Aztec codices are known to have survived the conquest since they were all burned during the conquest war. The books are presently in the collections of the Museo de América, Madrid; Sächsische Landesbibliothek—Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, Dresden, Germany; Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; and Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico City.

Enrique Chagoya, (Details) Popol Vuh de la Abuelita del Ahuizote (People’s Book of the King Ahuizote’s Granny) (Oakland: Magnolia Editions, 2021). L21.63.6. © Enrique Chagoya, Images courtesy of the artist and Magnolia Editions, Oakland

It is incredible that historians have been able to write volumes about the content of the few surviving books of Aztec, Mayan, and Mixtec-Zapotec origins (complementing the writings on ceramics, murals, and sculpture in archeological remains). This history made me ask the question: What would it be like if one of those book artists (known as tlacuilos) could travel in time to our contemporary world and depict our reality? My books are an attempt to answer this question. They are painted or printed on the same handmade amate paper (made from the bark of the native amate tree, of the fig family) used by ancient bookmakers. Amate is still handmade in the mountains of the state of Puebla by the Indigenous Otomi people. I feel lucky that the production of the paper survived the conquest war and three centuries of colonial censorship by the Holy Inquisition on indigenous books and papermaking, which was punishable with imprisonment or a death sentence.

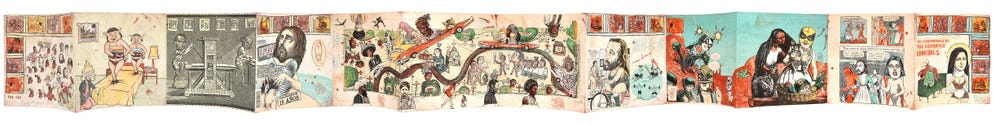

Enrique Chagoya, The Misadventures of the Romantic Cannibals, 2002. Lithographic book hand printed in color, 7.5 in. x 90 in. Edition of 30. Published by Shark's Ink, Lyons, CO. © Enrique Chagoya, Image courtesy of the artist

My books/codices present a nonlinear narrative, with a visual language that may be interpreted differently by viewers depending on how many symbols are recognizable to them. These books have taken me to many places I never expected to visit (socially, culturally and geographically), including controversy. One such place was in Loveland, Colorado. My work was attacked there in October 2010, when a religious fanatic destroyed one of my lithographic codices (The Misadventures of the Romantic Cannibals from 2002). In this work I presented a visual critique, with humor and satire, of the homophobia and hypocrisy behind the Catholic Church’s discrimination against same-sex marriage and its militant stand against birth control while its patriarchal leaders did nothing to stop the sexual abuse of children and nuns. The book had been included in the exhibition The Indelible Ink of Bud Shark, which featured the collection of prints from the publisher of my work, at the Loveland Museum.

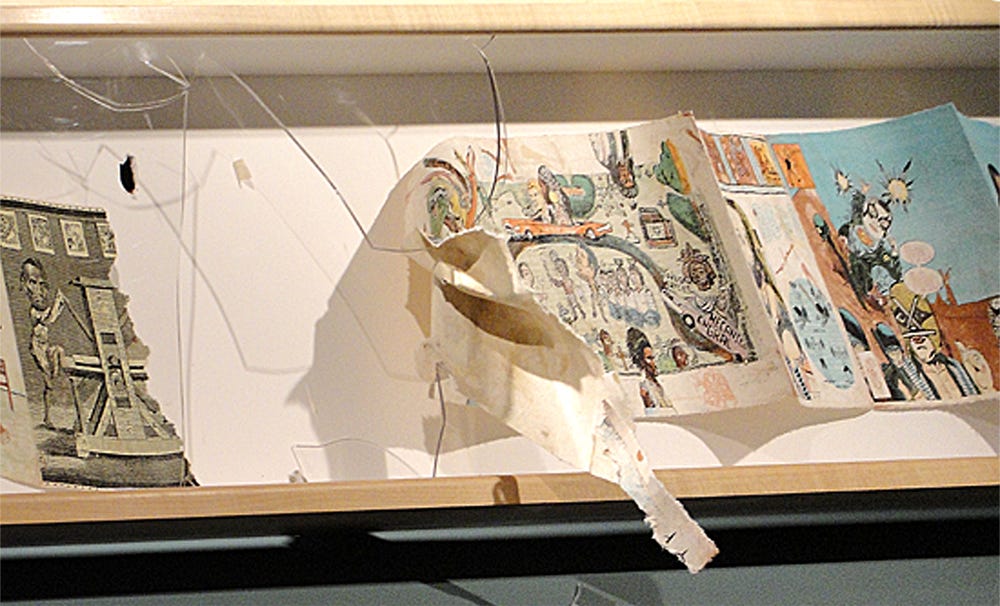

Detail, destruction of framed book The Misadventures of the Romantic Cannibals at Loveland Museum, Loveland, CO 2010. © Enrique Chagoya, Image courtesy of the artist

My work was picketed by a local group of fundamentalist Christians and members of the Tea Party; I was even viciously attacked on Fox News without ever being given a chance to talk about the content and my reasons. Instead of turning off her TV, one offended woman drove her eighteen wheeler from Montana to Colorado to destroy my framed book with a crowbar. I guess nobody told her it was a multiple, a limited-edition print, and not a one-of-a-kind work. Thankfully one local evangelist, pastor Jonathan Wiggins from the Resurrection Fellowship, agreed with my point of view, defended my artwork, and refused to join the picket line outside the museum, standing up to pressure from his large congregation of about three thousand members (many of whom left the church as a result). We both received hundreds of pieces of hate mail, death threats, and much unwanted publicity, but we became very good friends while facing our fears.

A few weeks later things calmed down, and we were quickly forgotten. Then Pastor Wiggins asked me if I would be willing to make a painting of Jesus for his church. I told him that I was not religious but if his congregation accepted a gift from me I would gladly do it. (As he risked his life to defend my work, I felt the responsibility to do it.) The congregation accepted, and I made a large painting with a resurrected Jesus, holding a banner displaying the word LOVE, in a style blending Mexican Baroque and Dutch religious paintings. The congregation loved it, paying for the shipping and inviting me to a reception in the summer of 2011. I was really scared to go, because I thought Pastor Wiggins or I could get shot and killed by some fanatic. (After so many reports of killings in Colorado for lesser offences, I was really worried.) But after thinking long and hard, I decided to go by myself and accept the consequences of making my art.

It was perhaps one of the most beautiful experiences of my career. They provided me with bodyguards, nobody tried to convert me, no religious conversations were forced among us, and the reception was well attended, including the rest of the pastors and their families. The large painting was hung high up on a big wall at the entrance of the church. I spoke to a very large crowd in their auditorium and thanked them for being open minded. I received a standing ovation. I got out of my art bubble, and the pastor got out of his religion bubble. It was a memorable dialogue. We remain friends, and the church now works with undocumented immigrants and denounces pedophilia in religious institutions. The Loveland Museum received much help from its membership as well; donations poured in thanks to Director Susan Ison (now a council member of the city of Loveland), who stood her ground against the protesters. The museum used the money to open a printmaking studio with a new press and started teaching art classes. There were two reviews of the incident in Art in America, one by Eleanor Heartney and another by Fay Hirsch. It was a happy ending to an otherwise horrific controversy.

I learned a couple of formative lessons from this experience. Art appreciation is deeply affected by context. What is accepted in one place and time may be subversive in another. Perhaps more importantly, I realized that art by itself may not change the world, but it is a door to walk into unknown territories and create honest dialogues with very different and often opposing constituencies that can only help change the world for the better.

Text by Enrique Chagoya.

Borderless: Artist’s Books by Enrique Chagoya is now on view at the Legion of Honor from October 30, 2021–March 6, 2022.