New Interpretive Lenses and Updating In-Gallery Texts

By Melissa Buron, Lauren Palmor, Thomas Wu, and Isabella Holland

February 18, 2021

As we at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF) address and redefine what being an anti-racist organization means for us, we are actively engaged in the ongoing work of personal reflection and dialogue. The insights gleaned from our collections, our staff, and the communities we serve have provided multiple sources of inspiration while we as a FAMSF staff confront our individual knowledge gaps. This work will continue beyond the present moment and it will be essential moving forward to maintain a critical perspective on the presentation of our collections.

One core aspect of our curatorial work in recent months has been to identify the racist and colonial narratives and perspectives that we have inadvertently and often unconsciously upheld. As we reassessed the fundamental practice of presenting and interpreting our permanent collections with fresh eyes and new perspectives, it became clear that several measurable adjustments could improve the inclusivity and diversity of the lenses through which we share information about the works in our care.

For example, curators in the European art department rewrote the gallery introductory texts, called "chat panels," which are currently installed in every gallery at the Legion of Honor. Areas of concern that these panels touch upon, among others, include: the conquest and colonization of the Americas by European powers beginning in the 15th century, the persecution of Muslims and Jews following the reunification of Spain under Catholic rule beginning in the 15th century, and the Trans-Atlantic slave trade during the late 15th–19th centuries. These new texts provide more expansive contexts for the works of art presented in each room.

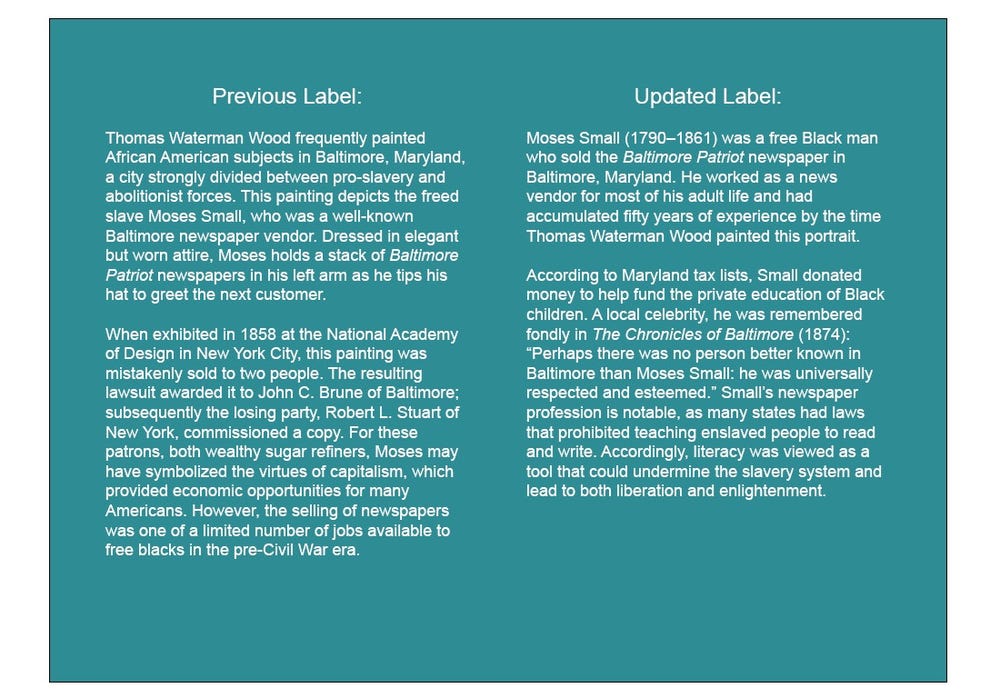

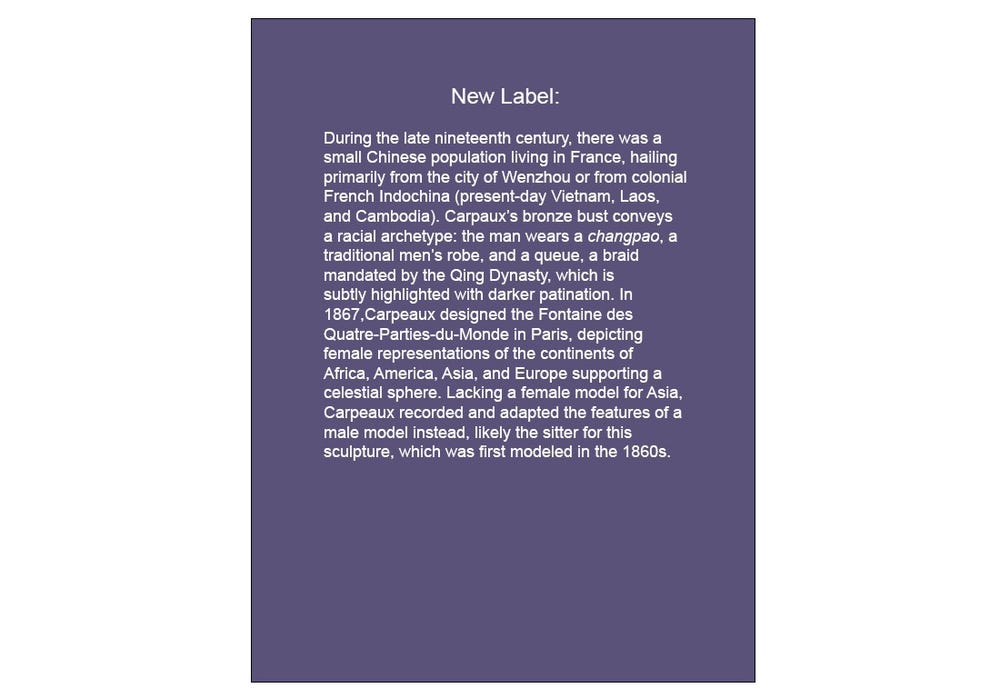

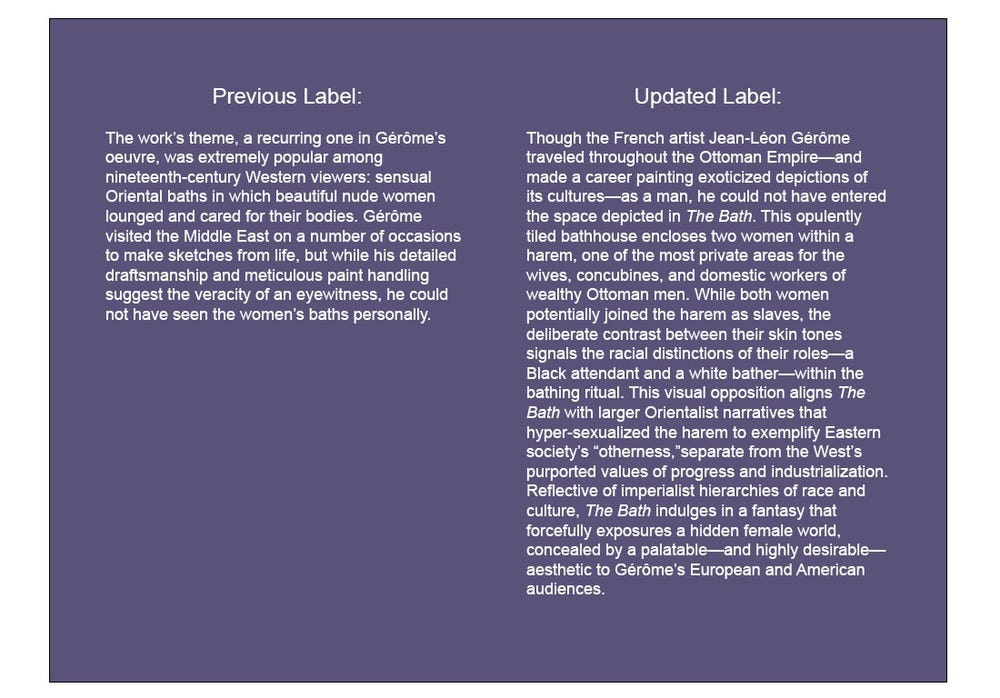

We have also written a series of new labels for individual objects in the permanent collection, two of which are highlighted below. Some objects received revised extended text, like the label for our Jean-Leon Gérôme painting, The Bath, written by Isabella Holland. Others, like a bronze sculpture by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Le Chinois (The Chinese Man), written by Thomas Wu, received an extended label for the first time.

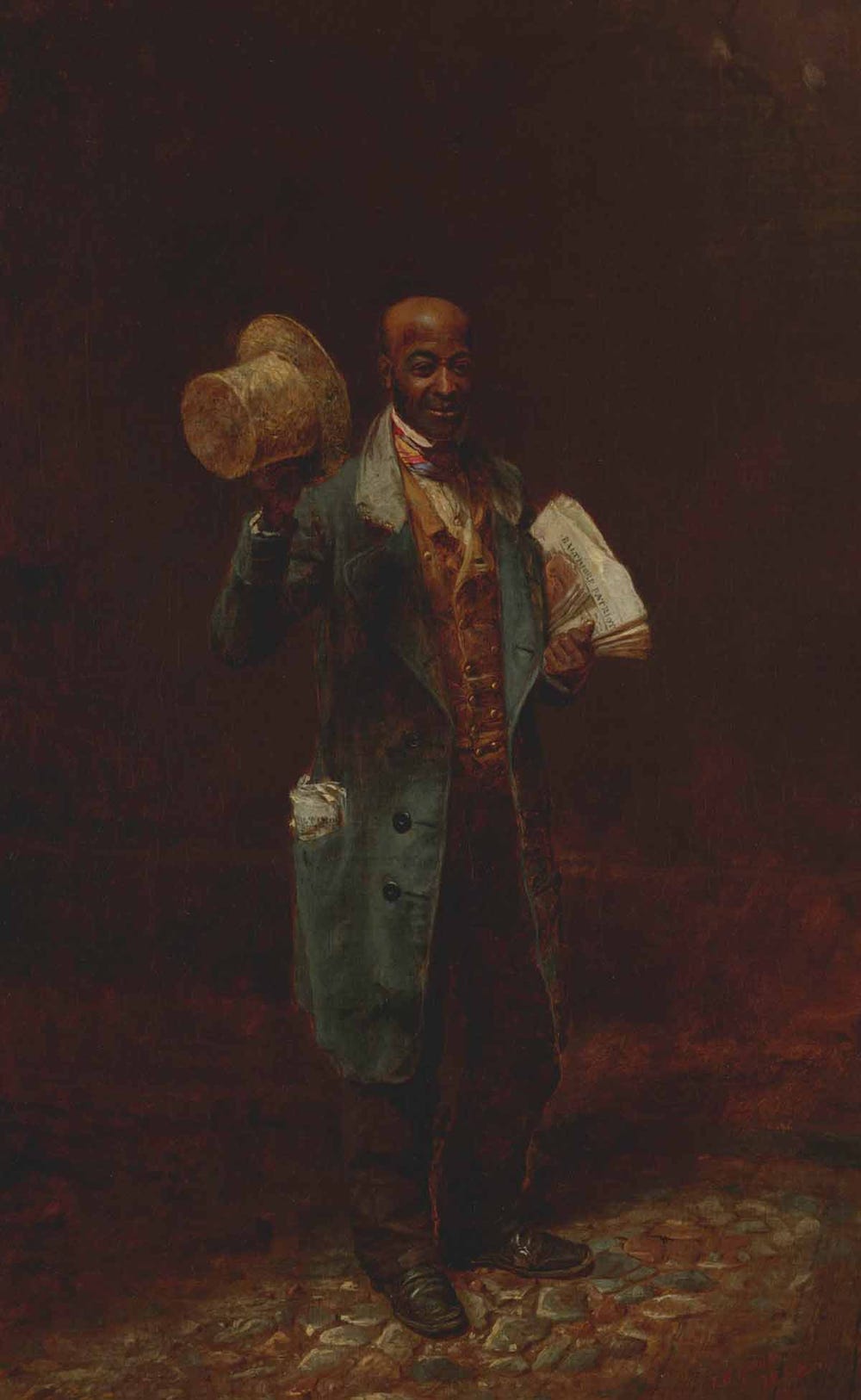

Similarly, new labels focused on historically underrepresented narratives were authored by the American art curatorial team. One example about the painting by Thomas Waterman Wood, Moses, The Baltimore News Vendor, 1858, written by Lauren Palmor, is included below. The new label positions the painting's subject—rather than the painter—at the foreground of the narrative. The challenge inherent in presenting any didactic text is telling a well-rounded story in the word count afforded by available space, however, these new interpretations expand the incomplete perspectives previously offered in the existing texts.

We also expanded the diversity of perspectives through which we understand the past by partnering with colleagues in our education department to engage with external readers who assessed these newly written didactics. This peer review identified areas of knowledge gaps, which helped to further explore the complexities of cultures, subjects, and the works of art themselves. Scholars such as Dr. Lizzetta LeFalle-Collins, Content Specialist/US Black Artists and Art of the Black Diaspora; Abram Jackson, Educator and adjunct faculty, College of Ethnic Studies, San Francisco State University; and Nitoshia L. Ford, Doctoral Candidate, African American and African Diaspora Studies, University of California Berkeley were paid consultants who reviewed these texts, providing an expertise and perspective that is evident in the final results.

Below you will find short descriptions of specific texts and the new processes through which they came to fruition.

- Melissa Buron, Director, Art Division

Thomas Waterman Wood, Moses, The Baltimore News Vendor, 1858

The changes to the object label for Wood’s painting of Moses Small, actually had their inception in November 2018, when I welcomed Douglas P. McElrath, the Director of Special Collections and Archives at the University of Maryland, to the American Art Study Center at the de Young Museum. McElrath came to the Study Center to conduct research for a biography of Moses Small. We spoke about Small’s status as an extraordinary individual whose life can serve as an entry point into the social history of freedpeople in the early nineteenth century, and this meeting alerted me to the much larger possibilities for rich biographical interpretation inspired by Wood’s portrait.

Thomas Waterman Wood, Moses, The Baltimore News Vendor, 1858. Oil on canvas, 24 1/8 x 15 in. (61.3 x 38.1 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Henry K.S. Williams, 1944.7.

The new label aims to center Small’s biography, providing an opportunity to learn more about the ways in which free Black Americans found ways to pursue their livelihoods and lift up their own communities. While the former label focused on the roles of the artist who realized this work and the collectors who desired to possess it, the updated text shifts the focus to the life and character of Small, the “universally respected and esteemed” newspaper vendor.

This text was included in a global critical reexamination of the labels found throughout the American galleries, which we appraised through a new lens of scholarship, urgency, and honesty. We aimed to proactively and critically address the problematic histories and issues inherent in some of the collection’s American objects, including associations with imperialism and colonialism that had previously been omitted from our wall labels. This project was supported by educators and curatorial colleagues, as well as three external readers (LeFalle-Collins, Jackson and Ford) who all brought important new perspectives to this undertaking.

- Lauren Palmor, Assistant Curator, American Art

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Le Chinois (The Chinese Man), ca. 1872

While changes in our galleries are often prompted by temporary exhibitions and the installation of new acquisitions, it is equally important to periodically rejuvenate existing permanent collection installations and materials. During the months of the ongoing pandemic, galleries at the Legion of Honor have been refreshed and outfitted with new or updated didactics, which consist of the labels, panels, and other written materials on the walls of gallery and exhibition spaces that identify and interpret the objects.

Organized in a “tombstone” format, a label identifies an object by its maker, title, date of creation, materials, credit line (how the object entered our collection), and accession number (a unique record number used to track the object). While all labels include this essential information, some also include a paragraph that provides background information and prompts visitors to look more closely at certain aspects of an object—an extended label.

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Le Chinois (The Chinese Man), ca. 1872. Bronze on marble base, 27 in. (68.6 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Collis P. Huntington Memorial Fund and Walter Buck Fund, 1968.2

A bronze bust by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (French, 1827–1875) depicting a Chinese man, titled simply Le Chinois (The Chinese Man) (ca. 1872), has received an extended label which, for the first time, provides historical context. This object raises questions, such as who is the subject? What was the artist’s intent or the sculpture’s purpose? The new text addresses Carpeaux’s depiction of an unnamed “Chinese man,” of a racial archetype, by explaining why it was probably created, defining details of the subject’s appearance, clarifying the possible origins of the model, and placing the sculpture within the context of French imperialism in Southeast Asia during the nineteenth century.

The label text was initially drafted by curators in the Museums’ European Art department. It was then reviewed by the Education department and external scholar Dr. LeFalle-Collins, who specializes in African American art and depictions of race, and edited by the Publications department. Label revisions, such as this one, follow the Museums’ new interpretative approach that seeks to engage Legion of Honor audiences with the most pressing issues in the field of European art history.

- Thomas Wu, Curatorial Assistant, European Decorative Arts & Sculpture

Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Bath, ca. 1880–1885

Another object that received a new label as part of the European Art department’s didactic review was Jean-Léon Gérôme’s (French, 1824–1904) The Bath (ca. 1880–1885). In writing this new label, it was crucial to address The Bath’s explicit Orientalist context in its depiction of two exposed women—a Black attendant and a white bather—enclosed within a harem bathhouse. A starting point in the rewrite was to acknowledge that The Bath’s original label description did not visually unpack, or even make mention of, the identities of the two women (both potentially slaves), and the overt racial implications of their two roles within the central bathing ritual.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Bath, ca. 1880–1885. Oil on canvas, 29 x 23 1/2 in. (73.7 x 59.7 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Mildred Anna Williams Collection, 1961.29

Before writing the new text, extensive research aided my understanding of the Orientalist, and more specifically the harem, phenomena in the 19th century European imagination. While art historical staples like Linda Nochlin’s 1989 “The Imaginary Orient” were consulted, more recent publications–like this article from The Root–were seminal in my understanding of how scholars of today are positioning the work of Gérôme (an artist constantly debated by art historians). Finally, the new label underwent extensive revisions that involved colleagues from the Education and Publications departments and Dr. LeFalle-Collins. The editing process was instrumental in restructuring the label and pushing for a critical tone to flesh out the painting’s visual oppositions: Blackness/Whiteness, East/West, and male (viewer)/female(subject).

As the first painting in the European Art collection to undergo a complete label rewrite, The Bath, and the cross-departmental process involved to produce its new label, provides an important precedent as our department seeks to present stories about our collections that go beyond the traditional European art canon. While previous didactic labels in the Legion of Honor focused heavily on relating an object to its maker’s career, our department is now engaging with an interpretative approach that provides audiences more insight into the historical context of an object’s creation. The year 2020 has been challenging for arts institutions, but a silver lining of extended closures has been the opportunity to refresh galleries and take steps toward addressing the darker aspects of history that our collections touch upon. Producing new interpretive texts like extended labels has been a learning experience for the various departments involved and we hope that visitors will likewise learn from them as they enjoy the revitalized galleries.

- Isabella Holland, Curatorial Assistant, European Painting

Our Ongoing Responsibility

Beyond labels in galleries, we have also started commissioning and co-authoring web articles, which invite community partners and scholars from communities of origin to help us interpret and present works in the collections. (Here is one recent example about a Luba figure on view at the de Young museum.) Finally, we also reexamined the thematic lenses through which we assess the collections, resulting in five new themes that will guide our ongoing interpretation of the collections: Dynamics of Power, Systems of Belief, Ideals of Beauty, How Things are Made, and Ecologies of Place.

The saying about hindsight being "20/20" feels apt. This challenging period has brought so much into focus, such as the importance of our permanent collections and resilience of our colleagues, teams, and community partners. This moment in time has been critical for internal work–both personally and at an organizational level. The examples presented in this article are just a few first steps as we commit more deeply to our work as anti-racist museums. Remembering that we are temporary stewards who care for our collections, our colleagues, and our communities–especially in challenging times–encourages me to continuously reflect on the opportunities inherent in our work and what an honor it is to interpret the collections in our care.

- Melissa Buron

Further Readings

- Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College: “How Can Museum Labels Be Anti-Racist?”

- Getty Iris Blog: “Rethinking Descriptions of Black Africans in Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Art”

- FRIEZE: “Harvard Art Museums Update Painting Labels to Reveal Histories of Slavery and Sexism”