The costume and textile arts collections at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco are incredibly broad in scope, spanning multiple continents, media, and time periods from the ancient to the contemporary.

In the 1940s, the Bay Area established itself as a prominent center for fiber art, with the Museums becoming an integral part of this vibrant community. We continue to foster relationships with leading fiber artists, and hope many will submit entries to the exhibition, The de Young Open. In the past two years, we have received a number of contemporary works of art from leading fiber artists, a few of which are highlighted here.

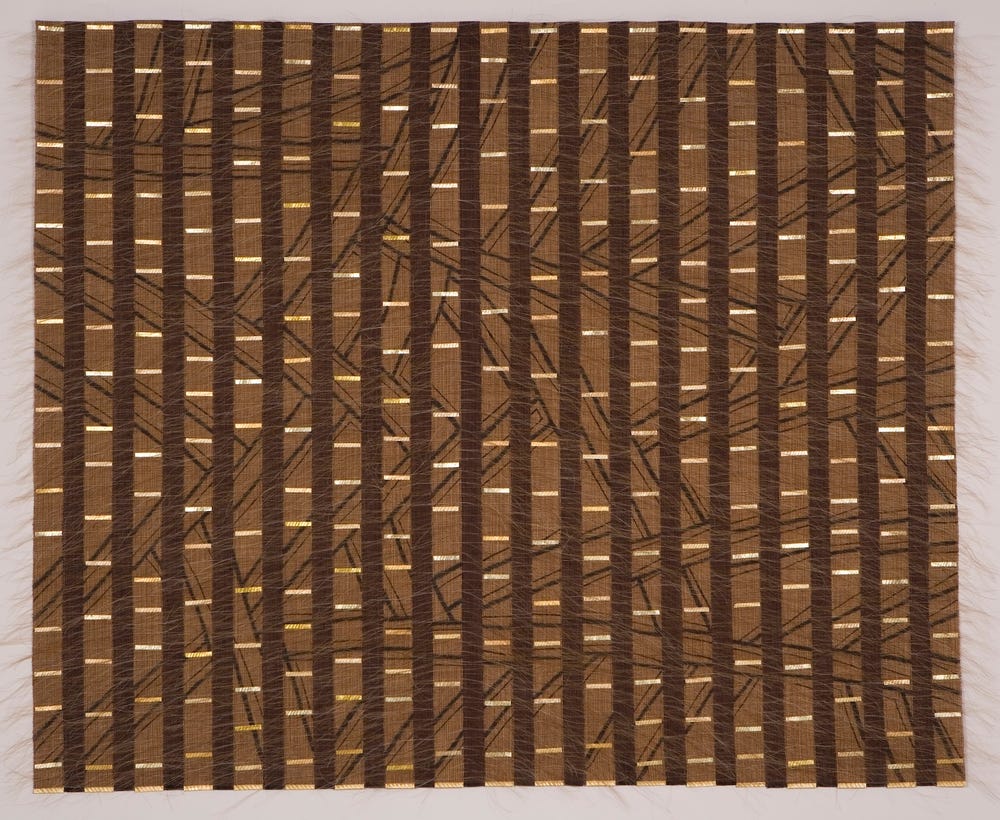

Adela Akers, Traced Memories, 2007. California Linen, horsehair, metal foil and paint, 48 x 58 in. (121.9 x 147.3 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Dr. Jorge Nieva, 2018.49. Courtesy of the artist

Adela Akers, Traced Memories, 2007

A leading American fiber artist known for her large sculptural wall hangings, Adela Akers shifted her practice when she was in her mid-80s to include more delicate materials like horsehair, linen, and recycled metal foil. Born in 1933 in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, and raised in Havana, Cuba, Akers received a degree in pharmacy from the University of Havana before moving to the United States to study at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Cranbrook Academy of Art. For more than twenty years, Akers taught at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University in Philadelphia. It was upon her retirement in 1995, when she moved to Sonoma County, California, that she entered a particularly prolific period in her career. Retirement offered her the time for artistic experimentation, and she continues to work in her studio on a daily basis.

Akers cites her background in science as influential to her work, which relies equally upon mathematical discipline, hand weaving, and organic processes and materials. Her work is both process and material driven, with her wall hangings taking up to three months to complete. She begins each work by hand-drawing a cartoon in an approach similar to that of tapestry weavers. These drawings are then scaled to size and transferred by means of a painted warp application. She then weaves thin strips, allowing for the long horsehair wefts to extend beyond the edges. Once the strips are woven, she arranges them into a pattern. She then sews hand-cut strips of recycled metal foil onto the woven surface. For Akers, this repetitive process is a time to be self-reflective, as she began this series as a memorial to dear friends she had recently lost. Traced Memories (2007; above,) the first work by Akers to enter into our collections, resonates specifically with our collections—Akers cites the Mbuti bark cloth in our holdings of African textiles as a source of inspiration.

Learn more about Akers on KQED’s Spark.

Liz Whitney Quisgard, Seven Clones, 2012–2017. Acrylic yarn on buckram (satin, running, raised fishbone, and cretan stitches), 72 in. (182.9 cm) (length per textile). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Anonymous gift, L19.12a–g. Courtesy of the artist

Liz Whitney Quisgard, Seven Clones, 2012–2017

Nationally renowned artist Liz Whitney Quisgard recently gifted a major artwork to the Museums. Quisgard’s artworks are recognized by their exuberant color palette and geometric patterns that evoke the scintillating shapes of Byzantine mosaics, Oriental carpet motifs, and Islamic geometric forms.

Quisgard emerged in her practice during the Abstract Expressionist era of the 1950s and 1960s, and since then, has worked across painting, sculpture, and fiber art. Born in 1929 in Philadelphia, she attended the Maryland Institute School of Architectural Design and Drafting, and studied color field painting with renowned artist Morris Louis in 1958. In 1966, she graduated from the Maryland Institute’s College of Art and earned her master of fine arts degree from the Rinehart School of Sculpture. In 2001, she was awarded a Pollock Krasner Foundation grant.

—Liz Whitney QuisgardMy goal is to surprise and engage the mind by seducing the eye. Toward that end I rely on pattern. We all understand a row of triangles, a strip of squares, an arrangement of circles and swirls. No need to ask their meaning. They simply are what they are. They speak to us universally and without apology.

Her textile hangings are formed by the stitching of lightweight acrylic yarns into stiff buckram, and are worked in a diverse array of colored threads and stitch techniques that attest to her mastery of color and texture. Seven Clones (2012–2017) is formed from seven separate textiles that, when displayed together, form a single work of art. The individual components were conceived to be exhibited in two different configurations, allowing for some diversity in their display. For an artist whose output is formed by an emphasis on the visual aspect of visual art, Quisgard notes, “Though they are identical on the outside, each one is different on the inside. That is the whole point.”

Learn more about Quisgard’s work.

Deborah Corsini, Into Tumucumaque, 2002. Wedge weave tapestry, 42 x 29 in. (106.7 x 73.7 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of the artist, 2019.44.2. Courtesy of the artist

Deborah Corsini, Into Tumucumaque, 2002

Deborah Corsini (b. 1950) has pursued her lifelong passion for weaving through her work as a California-based artist, lecturer, and teacher and as a former curator with the San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles, as well as a former board member of the Textile Arts Council, the curatorial support group for the textile arts department. Since 1973, her work has appeared in innumerable national and international solo, group, and juried exhibitions and is housed in dozens of private and corporate collections and in government embassies. In the spring of 2019, Corsini generously donated three of her tapestries dating from 1985 to 2005 to the Museums.

While Corsini has experimented with a variety of textile techniques—including ikat, rag-rug weaving, tablet weaving, and surface design—her primary art form is tapestry weaving.

—Deborah CorsiniThe interplay of color, line and negative space are the building blocks of my tapestries. The lines and forms are a part of a personal calligraphy and convey a suggestion . . . of things hidden and behind, of kinetic movement and space, and impermanence.

Corsini’s exploration of this medium is an ongoing creative process that continues to develop as she works. She adds, “I design on the loom—this process is interconnected to the actual woven process. I am always excited to see where the next tapestry will lead.” For her tapestry designs, Corsini has received the Award for Excellence from the American Tapestry Alliance. For the past 15 years, Corsini has been experimenting with the wedge weave technique, an eccentric-weft weaving technique used by Diné/Navajo weavers whereby wefts are woven at an angle to the warp.

—Deborah CorsiniThe dazzling designs created by Navajo weavers were my first teachers, and I owe my own intuitive style of designing from studying and appreciating their weavings.

K. Lee Manuel, Shaman’s Cape, 2003. Leather, feathers: painted, 63 x 72 in. (160 x 182.9 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Kelly Seymour, Peggie King, and Erin Reese, 2018.79. Courtesy of the artist

K. Lee Manuel, Shaman’s Cape, 2003

Last winter, the daughters of artist K. Lee Manuel made a sizeable donation of their mother’s work that offers an overview of her 40-year career. Born in Loma Linda, California, K. Lee Manuel (1936–2003) earned a bachelor’s of fine arts degree from the San Francisco Art Institute in painting. Manuel was an emerging artist in the mid-1960s, and her first body of work consisted of hand-painted cotton tunics in organic art nouveau–inspired patterns. Like the work of many fiber artists active during this period, Manuel’s work resonated both with the 1960s counterculture and with the burgeoning wearable art movement, of which the Bay Area would become a center.

Throughout her career, Manuel continued to hand-paint garments, jewelry, and accessories of varying materials, from cottons and velveteen to leather. In the mid-1970s, she began to paint intricate designs on individual bird feathers, crafting them into elaborate collars and wall hangings. The complexity of these works is remarkable—each feather is painted with a rich overlay of geometric, abstract, natural, and figurative motifs that evoke a range of world cultures, from Ancient Maya and Egyptian to Japanese theatre. These figures invoked a sense of power and took on a shamanistic quality. Manuel rarely explained her imagery in interviews, stating that the work should speak for itself. As the years progressed, her work became increasingly detailed. As she told Surface Design Journal in 1988, “Each piece has become a novel rather than a vignette.”

K. Lee Manuel, Shaman’s Cape (detail), 2003. Leather, feathers: painted, 63 x 72 in. (160 x 182.9 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Kelly Seymour, Peggie King, and Erin Reese, 2018.79. Courtesy of the artist

Diagnosed with cancer, Manuel embarked upon her final series: three “shaman’s robes” to serve as protective talismans for each of her daughters. The last work of art she completed was a cape for her daughter Peggy (above). A tour-de-force, the cape measures five feet wide by six feet long. Its leather substrate is covered with feathers painted with images of dragon masks from Kabuki theatre and small serpents. The Museums are greatly honored to be gifted this momentous work along with two tunics from the 1960s, a leather woman’s suit from the 1980s, and a feather collar.

Text by Jill D’Alessandro, Curator in Charge of Costume and Textile Arts.

Learn more about Costume and Textile Arts at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.