Naked Truth: The Radical Candor of Alice Neel’s Nudes

By Lauren Palmor

March 31, 2022

For Neel . . . the occasion of painting a nude was more an opportunity to make an unclothed portrait, for instead of reducing the female form to a mere object of flesh, she endowed it with personality, wit, and humanity, particularized with the sitters’ facial features and restored their dignity as human beings, rather than treating them as sexual objects.

—Jeremy Lewison

Alice Neel’s lifelong artistic engagement with the figure included a pronounced interest in the nude body. Her attraction to flesh was evidenced by works produced throughout her career, notable for both their unflinching honesty and lack of erotic charge. With her brush Neel transformed naked flesh into an occasion for psychological and emotional investigation. Unsentimental and unromantic, Neel’s nudes defiantly privilege human interest over sexual pleasure.

A true humanist, Neel was devoted to recording both the external appearance and interior life of her sitters. She was insatiably curious about people, as reflected in her persistent interest in having sitters pose naked. Many of her subjects later described the experience of being coaxed into stripping down in Neel’s apartment, even after carefully planning outfits for their sittings. Neel was interested in the feeling of directness she captured in her nude portrayals, as evidenced by the painterly pleasures of the soft bellies and sagging breasts she depicted. She painted in this manner indiscriminately: men and women, young and old, confident and reserved. When viewed as a unified “body” of work, Neel’s nudes offer a radical revision of one of Western art’s most persistent themes.

Alice Neel, Ethel Ashton, 1930. Oil on canvas, Framed: 31 11/16 x 30 1/16 x 1 1/16 in (80.5 x 76.3 x 2.7 cm). Presented by the American Fund for the Tate Gallery, courtesy of Hartley and Richard Neel, 2012 T13703. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner

The earliest nude featured in the exhibition Alice Neel: People Come First is her 1930 portrait of Ethel Ashton, a friend from the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art & Design), where Neel studied from 1921 to 1925. Painted in the Philadelphia studio Ashton shared with her classmate Rhoda Meyers, Ethel Ashton appears distorted and uneasy. Neel appraises her friend without flattery, looking down at her from a strange angle, as though she was hovering overhead with her brush. Ashton looks up, her self-conscious expression compounding the restless and awkward effects of the composition. She appears nervous, stripped down, her sagging curves and hunched posture channeling her discomfort. Each limb is severed by the edges of the canvas, and this visual amputation enhances the painting’s overall feeling of distortion. Her soft breasts fall over her belly, the folds of flesh exaggerated across her midsection and thighs. “Don’t you like her left leg on the right, that straight line?” Neel later asked. “You see, it’s very uncompromising. I can assure you, there was no one in the country doing nudes like this. And also, it’s great for Women’s Lib, because she’s almost apologizing for living.”

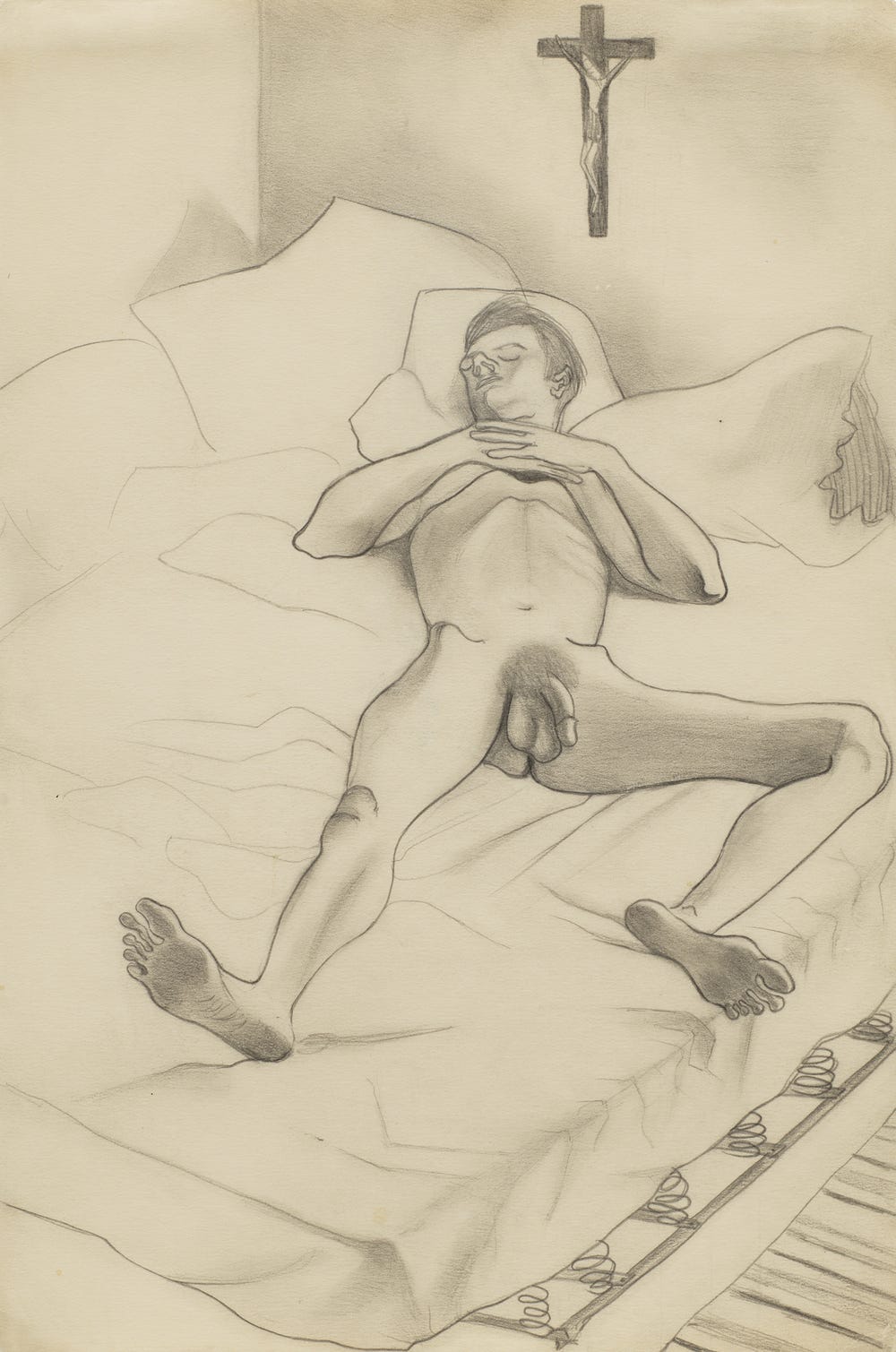

Alice Neel, Kenneth Doolittle, 1932. Graphite on paper, Framed: 22 3/8 x 17 1/8 x 1 1/2 in (56.8 x 43.5 x 3.8 cm). Private collection, courtesy of David Zwirner. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner

Created two years after Neel painted Ashton in her bewildered and bashful state, the drawing Kenneth Doolittle, 1932, appraises the nude male body without shame or discomfort. Rendered with Neel’s characteristic candor, the drawing depicts an intimate view of herthen-lover sleeping on a bed, his genitals arranged for maximum visibility. The soles of his dirty feet are also on full display, the perspective reminiscent of Andrea Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ, ca. 1480, an unusual depiction of Christ’s supine body in the moments after the descent from the cross. These connections are also suggested by the crucifix that hangs above Doolittle’s head — an atypically explicit inclusion on Neel’s part.

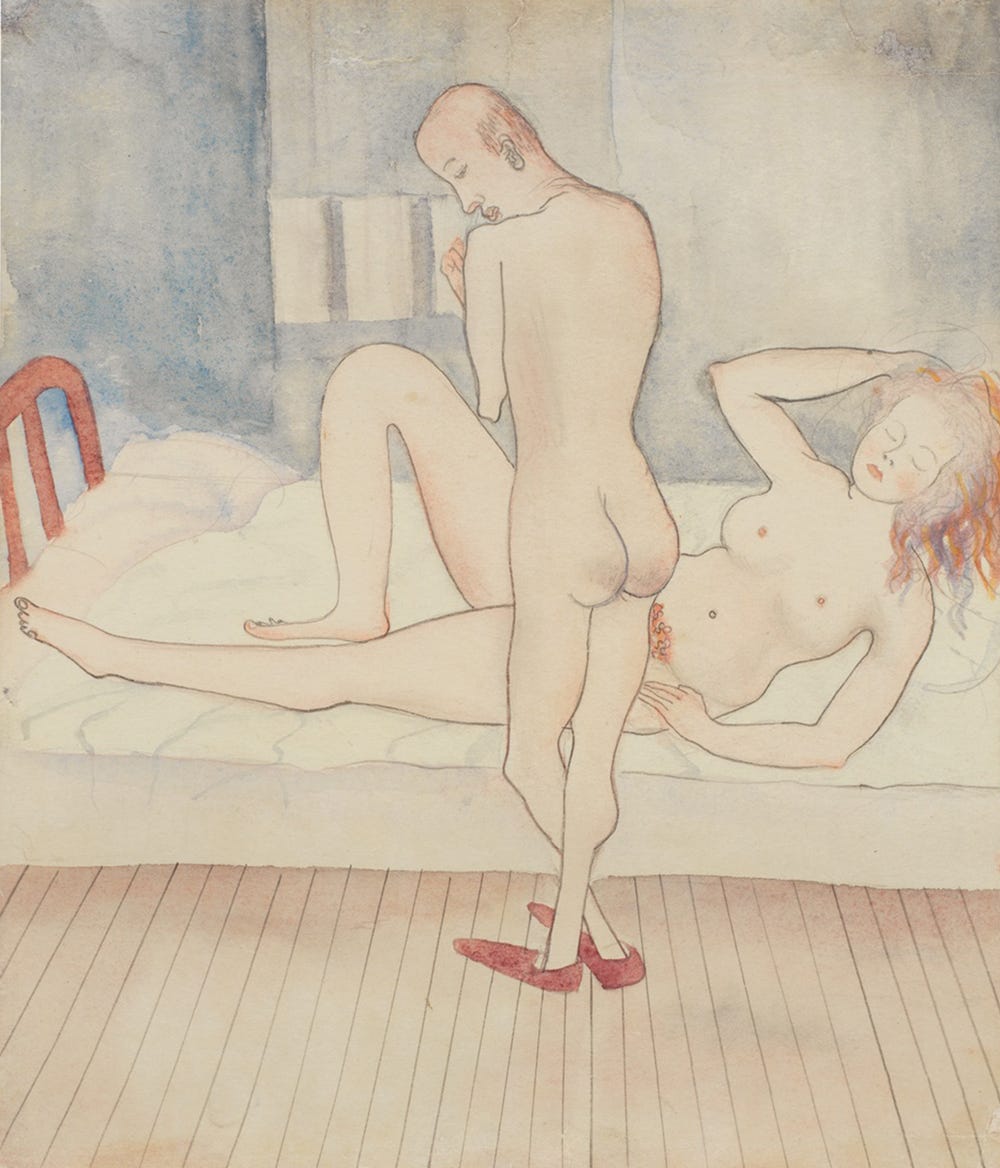

Alice Neel, Alienation, 1935. Watercolor on paper, Framed: 17 7/8 x 16 x 1 1/2 in (45.4 x 40.6 x 3.8 cm). Antonia Johnson Family Collection. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner

Neel’s depictions of her unclothed romantic partners often include precise details that counteract any perceived feelings of eroticism. Such features, like the bottoms of Doolittle’s dirty feet, ground Neel’s nudes in reality — what we see before us are real bodies reflecting real lived experiences. This is apparent again in a pair of rare early watercolors from 1935 that depict Neel with her lover in nude scenes that are stripped of romantic feeling. Untitled (Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom) graphically and bluntly depicts a likely pre- or postcoital moment between the two lovers in a bathroom. He urinates in the sink as she fixes her hair while seated on the toilet. Alienation shows Rothschild standing naked beside Neel, who lies in bed, its title suggestive of the troubled emotional and psychological dimensions of their coupling.

Neel’s engagement with the body persisted throughout the decades. By the time she began her remarkable series of pregnant nudes in the 1960s, she had already radically revised how other bodies were represented in Western art. Pregnant Maria, 1964, was the first in this new series. These paintings powerfully articulate the physical and psychological complexity of pregnancy. In 1962 Neel moved to a larger apartment at 300 West 107th Street on the Upper West Side near Columbia University. There she met Maria, a friend of some Columbia students who lived in the building. While she had previously painted a number of pregnant subjects and various nudes, Pregnant Maria combines these elements in one arresting representation. Confident and tranquil, Maria lies on rumpled sheets, her full belly filling the center of the composition. Neel painted the taut flesh of her pregnant stomach with swirling strokes of paint — peach, yellow, and green brushstrokes move with a dynamism and vivacity suggestive of the new life growing within.

Alice Neel, Pregnant Maria, 1964. Oil on canvas, Framed: 40 1/2 x 55 3/8 x 3/4 in (102.9 x 140.7 x 1.9 cm). Private collection. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner

When asked why she chose to paint pregnancy in this way, Neel explained:

It isn’t what appeals to me, it’s just a fact of life. It’s a very important part of life and it was neglected. I feel as a subject it’s perfectly legitimate, and people out of a false modesty, or being sissies, never show it, but it is a basic fact of life. Also, plastically, it is very exciting . . . I think it’s part of the human experience. Something that primitives did, but modern painters have shied away from because women were always done as sexual objects. A pregnant woman has a claim staked out; she is not for sale.

Nudity is employed to different effect in Cindy Nemser and Chuck, 1975, a tender portrait of the groundbreaking feminist art critic and curator and her husband, the coeditor of her Feminist Art Journal. Neel wanted to paint Nemser years earlier, but she had declined out of fear about how she would be depicted. In 1975 Nemser agreed to sit for Neel: “I believed she was the foremost portrait painter of the 20th century, and I considered it an honor to sit for her even if my portrayal didn’t turn out to be flattering.” The couple dressed up for their sitting, making an effort to wear fashionable clothes, shoes, and jewelry. As Nemser later described, “Alice took one look at us and said, ‘Oh, all those clothes, and that Mickey Mouse jewelry! . . . I just painted a dentist, so bourgeois.’ She said, ‘I know, I’ll paint you in the nude.’” Husband and wife appear unclothed, holding each other close and covering each other’s bodies. Their nudity is not a pretext for eroticism but a shared condition, a physical expression of their intimacy made even clearer by their instinct to protect one another.

Alice Neel, Self-Portrait, 1980. Oil on Canvas, Framed: 57 x 43 x 2 in (144.8 x 109.2 x 5.1 cm). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner. Image courtesy National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

For most of her life, Neel painted the bodies of others. At the age of 80, she finally turned her attention toward herself: Neel’s Self-Portrait, 1980, depicts her aging body, rendering visible the cumulative physical effect of six decades spent sitting at her easel. Painted four years before her death, Neel’s monumental and defiant Self-Portrait was executed during a period of unparalleled recognition and success. After finally achieving the critical acclaim so long overdue, Neel committed herself to the canvas with unprecedented aplomb. Wholly unselfconscious, the artist meets the viewer with a challenging stare. A steadfast representation of the passage of time is written across her wrinkled face, ruddy cheeks, and sagging breasts and belly. “My flesh drooping off my bones,” as she described it. Surrounded by halos of color, the figure of the elder artist is foregrounded in what otherwise appears to be an abstract composition, evincing Neel’s late-career reflection that all great painting has “good abstract qualities.”

While Neel’s nudes are all inherently unique and reflective of the psychology and appearance of her sitters, they share a certain directness. Rather than delight in sexuality, they offer unflinching candor. These uncompromising works attest to the various dimensions of Neel’s powers. “I do not pose my sitters. I do not deliberate and then concoct,” she said. “Before painting, when I talk to the person, they unconsciously assume their most characteristic pose, which in a way involves all their character and social standing — what the world has done to them and their retaliation.” Stripped down, her sitters are shown as they are.

Text by Lauren Palmor, assistant curator of American art at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Alice Neel: People Come First is on view at the de Young March 12, 2022 through July 10, 2022.

Sources Cited

- Flood, Richard. “Undergoing Scrutiny: Sitting for Alice Neel.” In Alice Neel, edited by Ann Temkin, 68 – 69. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2000.

- Lewison, Jeremy. “Showing the Barbarity of Life: Alice Neel’s Grotesque.” In Alice Neel: Painted Truths, edited by Jeremy Lewison and Barry Walker, 48. Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2010.

- Neel, Alice. Alice Neel to Patricia Hills. In Alice Neel, edited by Patricia Hills, 30, 141. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1983.