5 Works to Know from the Osher Collection of American Art

By Magnolia Molcan, senior web managing editor

April 18, 2024

Robert Frederick Blum (1857–1903), Venetian Gondoliers (detail), ca. 1880–1889. Oil on canvas, 181/2 × 285/8 in. (47 × 72.7 cm). Promised gift of Bernard and Barbro Osher. Photograph by Randy Dodson

From sweeping desert landscapes to Venetian views, the Bernard and Barbro Osher Collection tells the story of American art in the 19th and 20th centuries. Let’s take a closer look.

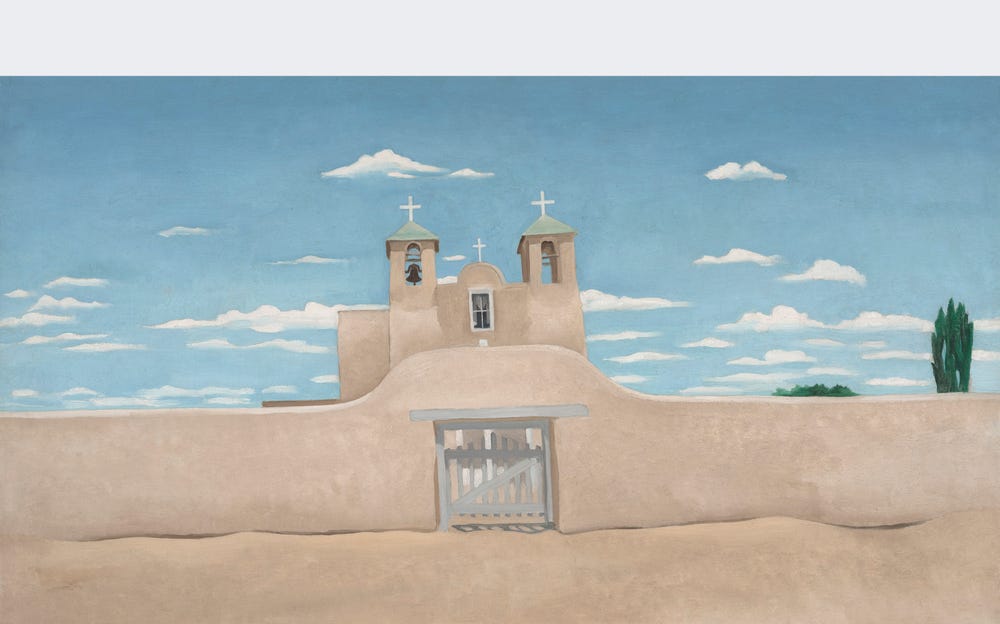

1. Georgia O’Keeffe, Front of Ranchos Church (1930)

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Front of Ranchos Church, 1930. Oil on canvas, 20 × 36 in. (51 × 91.5 cm). Promised gift of Bernard and Barbro Osher © 2024 Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Randy Dodson

Adobe architecture, sweeping desert landscapes, and mountain peaks. Georgia O’Keeffe made her first extended trip to New Mexico in the summer of 1929. She was enchanted by the brilliant light and endless skies, recounting: “When I got to New Mexico that was mine. As soon as I saw it, that was my country.” O’Keeffe’s love for this landscape is clear in her great series on San Francisco de Asís, often called Ranchos Church. This church inspired a generation of modernists — including O’Keeffe, and photographers Ansel Adams and Paul Strand. “Most artists who spend any time in Taos have to paint it, I suppose, just as they have to paint a self-portrait,” O’Keeffe said. “I had to paint it—the back of it several times, the front once.”

2. Charles Sheeler, Cat-walk (1947)

Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), Cat-walk, 1947. Oil on canvas, 24 × 20 in. (61 × 50.8 cm). Promised gift of Bernard and Barbro Osher © Charles Sheeler. Photograph by Randy Dodson

An early modernist, Charles Sheeler worked in both painting and photography. In the mid-1940s, he photographed a synthetic-rubber plant in West Virginia, using the photos as the basis for four paintings. In Cat-walk, Sheeler simplified the plant into overlapping lines, jutting catwalks, and interlocking shadows. By presenting the facility without soot or laborers, he created the fantasy of pristine industry. Sheeler was a student of William Merritt Chase, whose work we’ll look at next.

3. William Merritt Chase, Spanish Bric-à-Brac Shop (1883)

William Merritt Chase (1849–1916), Spanish Bric-à-Brac Shop, 1883. Oil on canvas, 29 1/2 x 48 3/8 in (74.9 x 122.9 cm). Promised gift of Bernard and Barbro Osher. Photograph by Randy Dodson. Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

William Merritt Chase was an American Impressionist who founded the Chase School (later Parsons School of Design) in 1896. He was also a collector, coming home from trips abroad with art, furniture, and antiques. Arriving in New York after a visit to Spain in 1882, he brought back so many antiques that he was detained by US customs officials. Chase filled his studio with these finds, regularly opening his doors to fellow artists, patrons, and the public as a way to market his work. Spanish Bric-a-Brac Shop depicts the type of antique store he would have visited on his travels. It also acts as a self-portrait, revealing the artist through the objects he admired, including the work of Diego Velázquez. Can you spot the portrait in the upper right? It’s a copy of Velázquez’s The Buffoon Calabacillas (1635–1639).

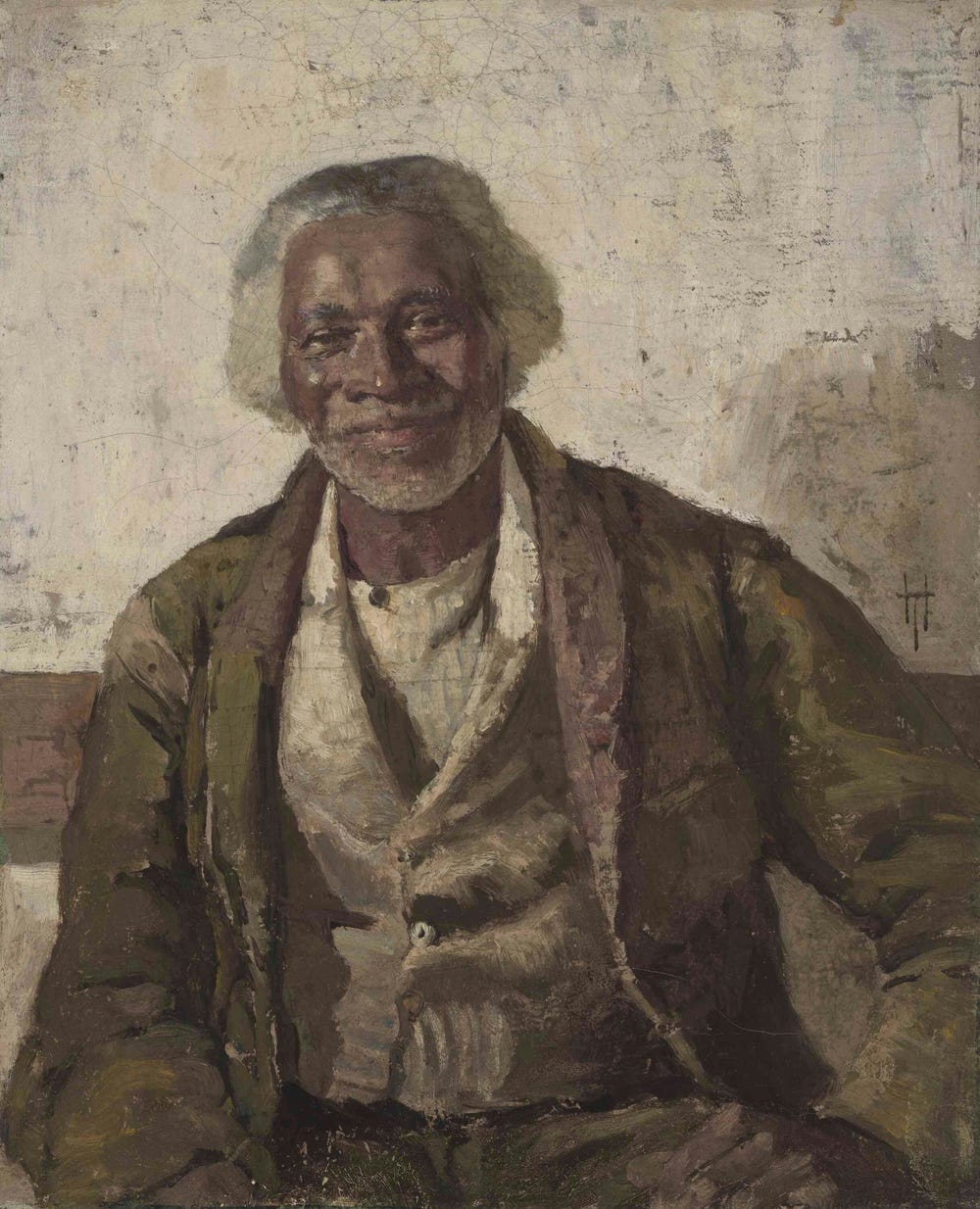

4. Thomas Hovenden, Portrait of Samuel Jones (ca. 1882)

Thomas Hovenden (1840–1895), Portrait of Samuel Jones, ca. 1882. Oil on canvas, 9 7/8 × 8 in. (25 × 20.5 cm). Promised gift of Bernard and Barbro Osher. Photograph by Randy Dodson

Thomas Hovenden married artist Helen Corson, member of a noted Quaker and abolitionist family, in 1881. They lived on her family’s property in Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania, a historic center of antislavery activity. Hovenden built his studio in the property’s Abolition Hall (named for the antislavery meetings that took place there). He became part of the community, and often featured his African American neighbors in his works. Hovenden’s friend and neighbor, Samuel Jones, was one of his favorite models. Jones was born in Maryland when slavery was still legal. He and his family settled in Pennsylvania in 1849, where he lived as a free man. Jones can be seen in at least six of Hovenden’s paintings, including our own Sunday Morning (1881). A departure from the artist’s staged scenes of everyday life, Portrait of Samuel Jones focuses on Jones as a person: relaxed, warm, and charismatic.

5. Robert Frederick Blum, Venetian Gondoliers (ca. 1880–1889)

Robert Frederick Blum (1857–1903), Venetian Gondoliers, ca. 1880–1889. Oil on canvas, 181/2 × 285/8 in. (47 × 72.7 cm). Promised gift of Bernard and Barbro Osher. Photograph by Randy Dodson

Robert Frederick Blum was one of many American artists who studied in Europe during this period. In Venice, he met James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). Whistler liked the view from Blum’s room, and was known to make pastel drawings looking out his window. This allowed Blum to observe Whistler’s techniques firsthand. Whistler’s influence can be seen in the harmonious colors Blum chose for Venetian Gondoliers. The work’s viewpoint seems to be the middle of the lagoon, as if the artist himself was sitting in a gondola as he painted.