Minimal Michelangelo: The Journey of a Sketch

By Mauro Mussolin, art and architectural historian

October 31, 2023

Church of San Lorenzo in Florence. Photograph courtesy of Mauro Mussolin

Given Michelangelo’s remarkable body of work, why devote time to a scrap of paper featuring what seems like a commonplace and minimal sketch? Because it isn’t just a sketch. It’s a magnifying glass, allowing us to look closer at Michelangelo’s process and art. And it’s a record of time. The tears, folds, and stains on the sheet tell the stories behind its five centuries of existence and the long journey that carried it from Michelangelo’s hands to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

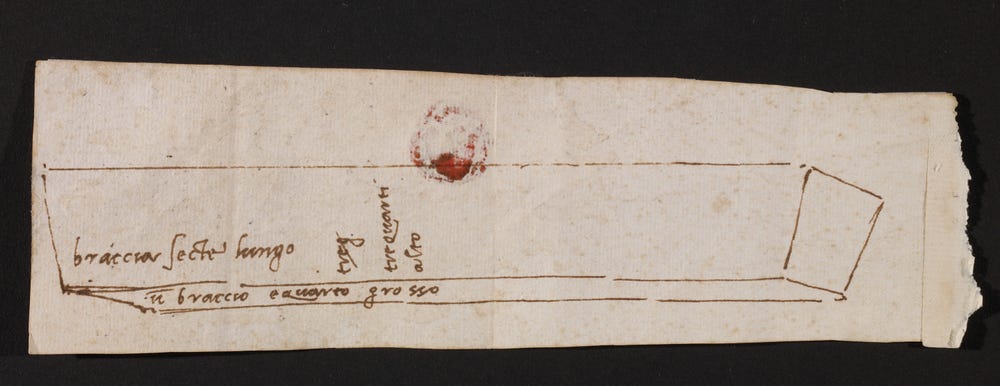

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), Diagrammatic Sketch of a Rectangular Marble Block, Inscribed with Measurements, ca. 1519–1530. Pen and brown ink, remnants of a wax seal on paper, 2 9/16 x 8 in. (6.5 x 20.3 cm). Museum purchase, Dorothy Spreckels Munn Bequest Fund, 2000.44

Project for a Pope

The first of these stories is about an immensely ambitious project commissioned by Pope Leo X, a project that became one of the most renowned architectural endeavors in the history of art. In 1516, Michelangelo was tasked with creating the facade of the San Lorenzo Church in Florence. For the first time, the roles of architect and sculptor converged. Michelangelo diligently studied the project, presenting a grand wooden model of the facade to the Pope two years later. He then meticulously designed every individual marble block on paper, providing precise measurements in Florentine braccia (equivalent to 22.9774 in. or 58.3626 cm).

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), Model of the facade project of the Church of San Lorenzo in Florence, ca. 1518. Wood, 85 x 111 7/16 x 19 11/16 in. (216 x 283 x 50 cm). Casa Buonarroti, inv. 518

On our sheet, Michelangelo notes the three main measurements of the block: “seven braccia long,” “three-quarters (of a braccio) tall,” and “one braccio and a quarter thick.” These measurements should be understood as rough; the final dimensions of the installed blocks were intended to be slightly smaller. The trapezoidal shape suggests the block represents the lintel above two corresponding portals of the side aisles of the church.

Church of San Lorenzo in Florence. Photograph courtesy of Mauro Mussolin

Across Land, Sea, and River

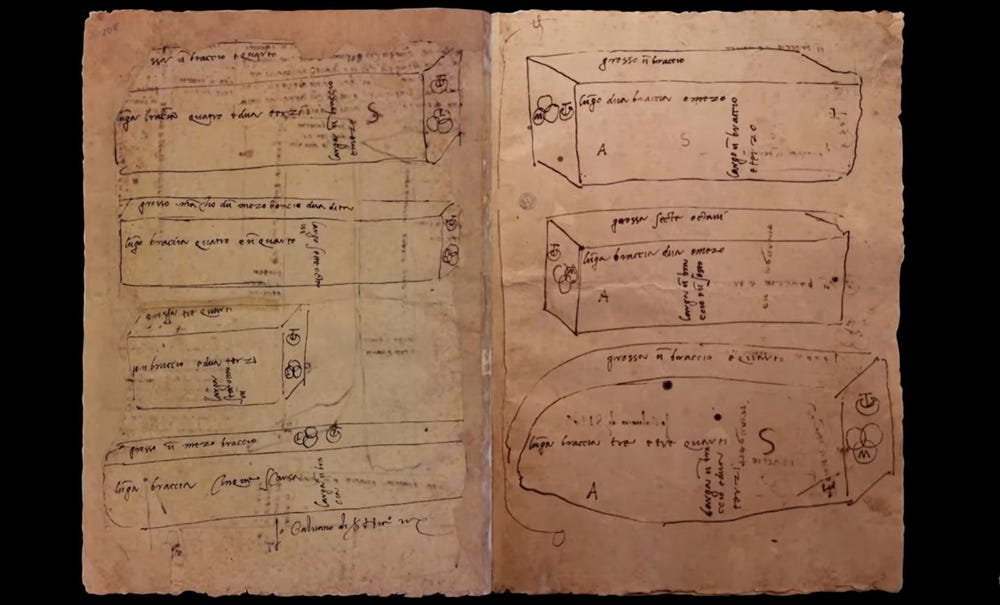

Michelangelo created numerous single sheets and bound folios adorned with dimensioned sketches of marble blocks, not only for the facade of San Lorenzo, but also for the marble structures of the Sagrestia Nuova (a mausoleum for the Medici family) and the funerary monument of Pope Julius II in Rome. These drawings served as tools for overseeing various phases of architectural design, streamlining the production and transportation of the blocks. This was one of many innovations introduced by Michelangelo that would later become widely adopted.

The designs provided instructions for quarrying the blocks, and allowed for the quantification of costs related to the material and its transportation. For the San Lorenzo project, this was a lengthy journey from the Apuan Alps to Florence, with four distinct stages: from the quarries to the port of Forte dei Marmi, by sea to Pisa, up the Arno River from Pisa to Signa, and over land from Signa to Florence. The block designs functioned as a kind of cargo manifest. In certain cases, they were even bundled and signed by the notary of Carrara, Galvano di Ser Niccolò, becoming legal transport documents and a form of insurance against potential theft, pilferage, or breakage.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), Quire containing sketches of marble blocks with measurements, signed by the notary Galvano di Ser Niccolò, ca. 1517. Red chalk and pen and ink, 12 6/16 x 8 9/16 in. (31.4 x 21.8 cm). Archivio Buonarroti, I, 82, cc. 223 recto-237 verso

Discovery of a Twin

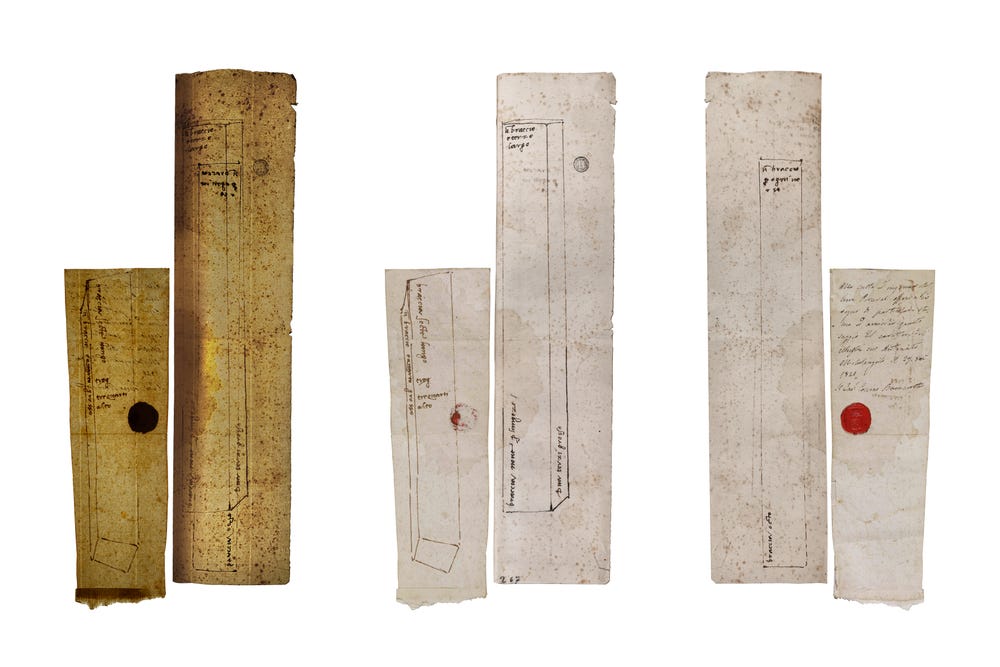

Among the existing block designs, only one features graphic and material elements matching ours: a design found at Casa Buonarroti, a museum dedicated to Michelangelo in Florence. It's possible that these two fragments were once part of the same sheet.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), Hypothetical reconstruction of the twin sheets containing marble blocks, the smaller one at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (Museum purchase, Dorothy Spreckels Munn Bequest Fund, 2000.44) and the larger one at Casa Buonarroti (Archivio Buonarroti, I, 150, c. 267 recto and verso)

Both are marked with a dark spot, likely from a spilled liquid. However, the mark on our sheet has been lightened due to a restoration that occurred before it came to FAMSF. Curiously, the drawings have inscriptions in opposing orientations. To explain this slight discrepancy, one could imagine a bifolium — with the two drawings traced on the outer pages, separated by the central fold. The stain would have occurred when the bifolium's pages were fully open.

A Gift and a Second Life

The idea that our sheet originated from Casa Buonarroti is further supported by an inscription on the back by Cosimo Buonarroti, the last direct descendant of Michelangelo. Cosimo had the habit of gifting small fragments of sheets with Michelangelo's drawings, authenticated by dedications, as tokens of friendship or esteem. Many of these featured block designs and were either auctioned off or found their way into various foreign collections.

A beautiful red wax seal, still perfectly intact, bears the Buonarroti family crest. A torn strip of paper in the right margin documents our sheet’s mounting in one of Casa Buonarroti's original albums. The dedication on the FAMSF sheet reads:

To the cultivated and gracious Miss Ann Parceval, as a token of special esteem and friendship, this sample of the work of her illustrious ancestor Michelangelo, on October 27, 1842. The Knight Cosimo Buonarroti.

This Ann Parceval may be the granddaughter of Michael Henry Perceval, the chief of customs in Quebec and the builder of Spencer Wood estate, now Quebec’s Government House. His wife, Anne Mary, was a botanist and the daughter of Sir Charles Flower, who served as the Lord Mayor of London.

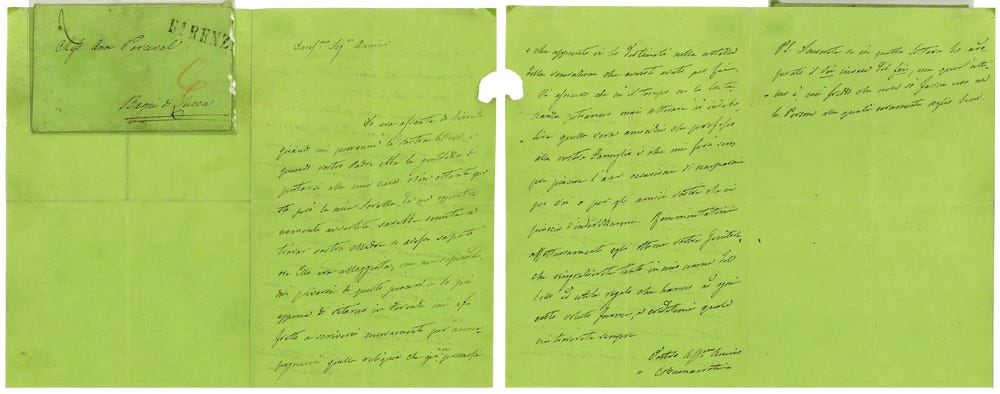

Letter from Cavalier Cosimo Buonarroti to Ann Parceval on October 27, 1842. Department files, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

In FAMSF's object files, we still have the letter that accompanied our sheet, filled with expressions of esteem. The address on the envelope is intriguing. It is from Bagni di Lucca, one of the most famous and well-frequented Italian spa resorts of the time, where Ann Parceval was staying with her parents. The folds in the thin, lemon-green paper perfectly match those on Michelangelo’s sheet, providing evidence that this precious gift was sent through Tuscany’s regular mail service.

Legacy

Even this simple sheet by Michelangelo reveals multiple stories: a project for a pope and a major architectural achievement; the adventure of a marble block across land, sea, and river; the possibility of the sketch being reunited with another that still resides in its native abode; and the second life of a ripped piece of paper, transformed into a precious gift and ending up in a far-off land. Most importantly, it gives us insight into the practical work and everyday methods of an artistic genius.