-

Local Voices S3E6 - Catherine Wagner Air Date: 5.24.21 Length: 33:36 Music: AWEN - Your Voice Produced by: Supervillain

Speakers Francesca D’Alessio, Catherine Wagner

Francesca D’Alessio 00:03 We think of artists as storytellers and visionaries who bring beauty into life, but they are also creative problem solvers, researchers and scientists in their own right. Artists can transform traditional research and investigation into works of art that communicate exploration and creative solutions. Today I will be speaking with Catherine Wagner, a conceptual multi-disciplinary artist, and investigator with a deep appreciation for science. Wagner is a professor of studio art at Mills College, and has traveled the world working in photography, as well as site specific art installations. She lectures intensively at museums and university and is a longtime friend of the de Young Museum, collaborating with us on various projects, including the inaugural exhibition that celebrated the opening of the remodel de Young Museum in 2005. So what was the first piece of art you remember making and being excited about, you know, where did your career as an artist start?

Catherine Wagner 01:22 I mean, it's a strange story. But I really think that and this goes back to why educators are so important. I was somebody who, in high school, did not feel engaged with a lot of the courses, I didn't think that there was enough room to have kind of multiple ways of thinking about certain topics, whether it was history or mathematics. And not, there always seemed to be kind of like a finite answer to these things. And that just wasn't the way that my brain thought I was always thinking about, well, it could be done like this, or, you know, and so I found myself just not engaged.

Francesca D’Alessio 02:00 Did they consider you a troublemaker?

Catherine Wagner 02:03 Borderline

Francesca D’Alessio 02:04 Yeah

Catherine Wagner 02:05 Definitely borderline like it was also during the 60s in the Vietnam War. And so I was very engaged with, with what was going on in the world globally, and in turn with our community. And yet, when I found myself in classes, for instance, in art classes, or in some literature classes, where your mind could kind of begin to construct different scenarios, whether it was visually or philosophically in your head, that really, that grounded me, and I felt like I was interested in I could hang with that. And I could stay at me, I could stay in the class and be engaged. And it was a one professor who said to me, we were making photographs, and I can't remember what the assignment was, it was something about pans and light. And I remember, there was a construction project near the school. And there were there's people digging in the ditches. And I asked if they would come out so that I could photograph their hands. And so I mean, in this very kind of naive way, I mean, those hands were very marked with perseverance, and callous and age. And so I photographed these people's hands, and made those photographs and my teacher at the time said, I hope you're taking yourself seriously in regard to what you're doing. Kind of took me aback a bit, because I'd say I was somebody in in high school who didn't take myself seriously. Albeit, I was a very serious person. So there was that conflict there. And I have to say that, you know, in many ways that it kind of gave me a little prick about a sense of self-worth through thinking about what I'm doing, and the ways in which I'm kind of choreographing ideas visually.

Francesca D’Alessio 03:52 Right? Because the teacher is telling you, I'm taking you seriously you need to as well, I mean, that's the most powerful thing from a teacher.

Catherine Wagner 03:59 Absolutely. I feel like that that was some kind of turning point for me. And I have subsequently became an educator. And I became an educator, because I think that there's a period in high school, I think, really, people are searching for their identities. And they're searching for their identities. And they're trying a whole host of different identities on and what I noticed is that there's a lot of people who have amazing skills in terms of language or mathematics, but that they don't quite know how to express themselves. And when you put a visual problem solving question in front of them, where there is no right or wrong, it's a multi-faceted, problem solving situation that that gets resolved, if you will, visually, I noticed that people really excelled with that. And so I thought, Oh, this is so interesting. There's no SAT test in the world that would ever kind of tap the visual acuity of these people who have developed a very silent language. But albeit a language.

Francesca D’Alessio 05:01 Y'know, cuz I was just thinking these kids that don't think linearly that don't take the finite answer as truth are always labeled as troublemakers and they're not, you know, it's just a different way of learning. There's the seven different styles of learning visual being one of them. And so you know, I just imagine you are one of those kids. And to have a teacher who encourages you is such a powerful moment as aside from dismissing and saying, this is a bad kid, this kid is misbehaving, this kid isn't engaged. By recognizing how talented you are recognizing that you need to take yourself seriously. I mean, that is such a pivotal moment. That's such a game changer.

Catherine Wagner 05:40 I think it was for me, and it made me very aware that that's something that that I took with me, you know, at that young age,

Francesca D’Alessio 05:47 Why photography? What is it about photography that thrills you? I'm assuming you, you're using darkrooms, in high school.

Catherine Wagner 05:53 Oh, full analog, I mean, I wouldn't even known what the word digital meant. So full analog. And when I, when I went on to college, when I came back to the States, I got a job in the slide library. And in the slide library, they said, will you file these slides, to make sure they're being put back in the appropriate place. And so when in trying to sort out where the slides would be put back, I had to really look at them. I was like, Okay, here's this Francis Frith, 18, something rather, that belongs here. And then I looked at a lot of work in terms of history. And so in many ways, it was this kind of crash course in history, because I'm looking at all these different artists. And by and large, a lot of the slides, I was filing for the art history department, were photographic slides, historical 19th century. And so I thought I was looking at a lot of this work. And I was really kind of amazed that there wasn't another tool in terms of drawing, or painting that could kind of render that kind of information photographically. And I was really struck because the kinds of work I was attracted to was painting and sculpture. But then this, this photographic thing was happening, where I recognize that this tool, this tool, called the camera, delivers information in a way that I couldn't imagine any other tool doing that. And so in looking at a lot of these 19th century slides, and realizing like the camera obscura, and in all the early methods of drawing that came from like a lens based image, I started, it was kind of like, it opened up a lot of the world. And yet, at the same time, when I was looking at contemporary photography, I wasn't that interested, because the kinds of work I was living here in San Francisco, and the dominant themes in photo photography, at that time, were kind of the West Coast landscape. And there was a, you know, the F64 group and there was very strong landscape work, kind of moving in that world of Ansel Adams. And although that work was just exquisitely beautiful, to me, it reminded me of like, when the whole symphony stands up, and there's just this like, bom, bom, bom bom. And I was really interested in maybe the most silent flutist might like, play a few notes. And that was, I was interested in kind of making visible that which became invisible or that or that which looked invisible. So I kind of had a reaction or a little bit of a rejection to that to the West Coast school of landscape photography.

Francesca D’Alessio 08:33 Yeah, well, you know, there's something very interesting to that, where you're, you're really an artist, you have a very artistic aesthetic with the science work you do, if that makes sense.

Catherine Wagner 08:44 The times in which I was living in, and I'm talking now about 70s, the 70s, I was looking at, like, the cultural landscape around me. And there was a tremendous amount of construction going on. And I was thinking, well, actually, this is the landscape that I'm growing up around. And I'm not in Yosemite, I'm in an urban setting. And so I began thinking about what the urban landscape has to yield. And that's probably a transition that I became very aware of the fact that the kinds of ideas that I was talking about photographically were much more aligned to kind of philosophical ideals.

Francesca D’Alessio 09:22 And what is your process look like? And do you have a favorite camera that you always rely on? Or, like, what is it what is it normal shoot look like? And I imagine over the years your process has changed a lot.

Catherine Wagner 09:33 It's changed radically. But I have to say if I looked through kind of like the lineages and linkages of my work early on, I was always, I was always most interested in looking at architecture. And in many ways, I think architecture is one of the most important mediums of the 21st century because it it's this container. It's this container that holds culture. And I think all the ways in which buildings are made and they're purposeness paramount. To the way that culture moves forward or doesn't. So architecture was always something I was extremely interested in. But I think kind of very early on, I did a very early series called The California Early California Landscapes and probably more well known as the, the Moscone site. And the Moscone site is a giant well, now for people who live in San Francisco. It's a large Convention Center. But when it was first being constructed, it was an area South of Market, which has now become the cultural center of San Francisco. And what it was, was there was an industrial area of San Francisco and also a homeless area of San Francisco. And they didn't solve any of those problems in terms of homelessness, they took the people who were homeless on Third and Fourth Street, and they just pushed them up a few blocks to Sixth and Seventh Street. And so that, you know, 40 years later, has still not been solved. What did happen is that pushing of that silent line of demarcation of where does the city begin and end, that line became farther south, and thus, we have now South of Market. So I followed this, this construction site called the Moscone site for a period of six years. And I had a studio near there, when Gary and I received permission to photograph in the Moscone site, as long as I would wear one of those orange vests, and a hardhat. And I had that that construction site to myself on weekends. So I had the key, and I kind of was like my arena for research.

Francesca D’Alessio 11:34 That's amazing that I mean, you're like the mayor. That's really cool.

Catherine Wagner 11:39 So I was there, you know, religiously, every weekend, because I wanted to photograph when there wasn't a lot of things happening and construction wasn't going on.

Francesca D’Alessio 11:49 And you're photographing, I mean, you're on a construction site. So you're photographing half built pieces, and was it dangerous?

Catherine Wagner 11:57 When I think back about it, I'm like, oh, my God, how did they let me in there?

Francesca D’Alessio 12:02 I'm thinking, I can't imagine 2021, you know, you didn't have to sign your life away, or

Catherine Wagner 12:07 I think I signed everything away, it was like, take it all, I didn't have anything. So I was really intrigued with this giant construction site, intrigued and disturbed by what was happening in terms of how they moved the homeless population up to blocks. And so a lot of people were being incredibly displaced. But in terms of my own, like, philosophical thinking, here was the largest construction site I'd ever seen. They went down several floors, so it was a hole in the ground. And it was the building of a series of 26 columnless arches. So these columnless arches, it was a new architectural way of building. Imagine, you know, you start at point A, and then this columnless arch connects in this half circle to the other end to form this arch. So there, there was these very monumental, kind of iconic shapes of these rebars that were kind of stretching towards the sky, to connect with the other piece of the ground. And I thought that's so interesting that, you know, these columns are built of rebar, and then they're curved, so that you have to have this kind of semi-circle, and it connects two pieces of the earth. And I was fascinated with this idea of change. And that change is this, this metaphor for all of us, and that it's really the common denominator of all our lives. And so I thought, this site isn't really for me about these ideas about change these metaphors about archaeology in reverse, a lot of times you dig to find these archaeological artifacts, and in many ways I was photographing, to kind of look at future ruins. So that's why I call it archaeology in reverse. So it's like, I'm taking the methodology of an archaeologist, but I'm actually thinking about, will this be future ruins. So there was a wonderful kind of dance I was doing between thinking about the 21st century of what was to come, and not so much about the architecture of this building. But working very metaphorically upon about this site. And all the ways in which these kind of visual symbols became metaphors for the way I was thinking as an artist.

Francesca D’Alessio 14:20 Wow. And at the same time, you're documenting a specific time and space, because now the Moscone has, you know, I mean, that's a functional building that people are in and out of all day long, and that you were there in those moments. It was being built. I mean, that's amazing. Has the city asked you for those archives?

Catherine Wagner 14:40 So yes, the SFMoMA owns the portfolio of many museums on the portfolio. So it's not just specific to our area because other museums, the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley actually has a majority of the archive.

Francesca D’Alessio 14:57 Wow. I mean, those are so valuable for so many reasons

Catherine Wagner 15:00 Bringing it now to the 21st century. I am the artist who was awarded the commission to work on the central subway, the first subway that goes north south and I was awarded one of the Moscone site Commission for the central subway. And now those same photographs that are in the portfolio are like 15 foot granite panels, with those photographs etched in them. So it's very exciting to me that in my lifetime, this was probably the first important body of work I did, I did it and received a National Endowment of the Arts grant to complete this work. And that's close to 40 years ago. And now this work is going to be unveiled next year 2022. And they are those photographs from the mid-70s.

Francesca D’Alessio 15:48 That's so beautiful. I mean, that's so it's such a beautiful story sort of full circle, and that art is valued art still has a place our I mean, that's so wonderful. And you've showed me pictures of the etchings, which it blew my mind. I mean, they look like black and white photos. I mean, I have no idea how you were able to do that. It's amazing.

Catherine Wagner 16:10 There was probably three or four years of just research and development in order to learn how to etch granite, so that it had that kind of overall qualities of what paper can yield.

Francesca D’Alessio 16:22 Wow. I mean, I've never seen anything like it. I've never seen anything like it. It's amazing.

Catherine Wagner 16:27 When people can ride the subway, hopefully in 2020, they're going to see these large photographs 15 feet on granite that will take you back to the exact same place. I made those photographs 35 plus years ago. The central subway project has been like, oh, Mamma Mia. I mean, on and off and off and on. But ultimately, I think it really will serve a ridership, and it will help with the density of that downtown area.

Francesca D’Alessio 16:54 Absolutely. And everyone will be impacted as they ride the train. And it's going to be really stunning. And what do you hope people get from it as they walk past and see it?

Catherine Wagner 17:03 I hope that they experience the artwork in the same way they would in a museum, but now they're out in the real world. And there are some other really fantastic artists also within the station. I know, Leslie Shows has a wonderful piece. And it's truly like it's a museum quality experience.

Francesca D’Alessio 17:21 It's fantastic. I mean, when you showed me the picture, I thought it was a photograph. And then when you said it was etched in granite, I mean, I did a triple take exquisite. Are people going to be able to touch it and examine it? I mean, it's the wall, right?

Catherine Wagner 17:34 Well, you'll be right there. So I would wish they wouldn't. But if it was me and I was walking by I'd do it I would I am I am that person in the museum who touches

Francesca D’Alessio 17:46 Same, Is it hard to sort of release it to the public that way? I mean, you sort of lose control of your of your baby?

Catherine Wagner 17:54 Well, I think you know, as an artist and working for as long as I've had, I'm somebody who believes that when art leaves the studio, you don't own it anymore, it becomes a public domain, whether it goes to a collector's house or a museum, or in the case of public art, it goes out into the world. And I believe that artists become artists, because they're desperately trying to communicate. So to have artwork shared in whatever venue it is, I think that that gives it its full circle, because it's now being shared with other people who can bring what they want to it, they bring their own set of projections and their own set of circumstances and their own history, to whatever the artwork is, and find a way to kind of move and engage in it. And I'm an artist who believes that you hold the bar high, you never dumbed down the work because it's going to be in a public space. I'd say that's kind of maybe one of my issues with public art that I think that there's a lot of a lot more artists that could engage in public art, and really kind of raise the level of the dialogue that that can ensue from that.

Francesca D’Alessio 19:01 Absolutely. I mean, I think it's one of the greatest responsibilities of an artist. You know, yeah, I mean, you absolutely never want to dumb things down. We talk about our programming that way as well. You know, you keep the bar really high. And you just speak multiple languages, you keep it as accessible for people. And everyone can reach that bar,

Catherine Wagner 19:19 I had a very negative desire to work in public art initially, because I associated public art with going to a bank or a mall, and there would be some giant disk in the middle. And there was just the opacity of what it was, there was nowhere to enter it as a piece of art. And I knew it was there for decorative purposes. But I thought, God, there even missing the bone about that because there are ways to be aesthetic and decorative without having to make some kind of like what we call plop art. It's this thing and you just plop it in the center and it takes up space. So I was I really I ran the other way when people used to ask me to work on Public Art, because I just thought never, never, never.

Francesca D’Alessio 20:04 Hopefully the world is changing. And hopefully people are recognizing the power of public art and the dialogues that can come about. And you know, I hope so I mean, we do need to set higher standards for sure. So when do you know a piece is finished and ready to go out?

Catherine Wagner 20:20 In public art, because it's usually a commissioned piece, there's so many schematics, everything's really dialed in. So you're working towards the completion of that vision. In my studio practice, as an artist, it's a very different thing. Because it's like, I think when I start emulating myself, I think, Okay, I'm done, I think I've made that piece, I think I've talked about that. That's different, very different process. Because when you're in the studio, you're much more in a place of experimentation, when you're making work that's going to be seamlessly installed in a large architectural, civic building. All of that needs to be planned down to the 'nth, because you're working with engineers, architectural team, lighting designers, all of it. So it's from the beginning, you're a chess player, and you're working with the entire team. And there's a strategy that happens if I move this, then this happens. So that's a very different process than being in the studio and making work that's going to be for a museum exhibition.

Francesca D’Alessio 21:18 Right, yeah. And there's so many people that you're communicating with, I mean, is that tricky? What does that process look like for you having a vision in your head, and then talking with engineers about rebar? I mean, it's just amazing to me.

Catherine Wagner 21:31 I feel like it's more akin to making a movie because it's like, you might have the idea for that film. But in order to actually make that movie, you've got a huge crew of people that you work with. And so it's very different than having that dialogue that you have when you're in the studio, which is a much quieter dialogue, that your dialogue with yourself. And, you know, you're a one man band, when you are working on these larger scale projects, there's, you actually learn to work very collaboratively with a team. And I try to keep the same team when possible, because we all know how one another works. And so that's really, really important.

Francesca D’Alessio 22:07 Yeah, yeah, I can imagine where I mean, you develop sort of the psychic, you know, my team is like, amazing, and they can translate for me, and they know what I need before I need it. And yeah, I understand. I can imagine with these huge, large scale projects, you need good folks that you trust.

Catherine Wagner 22:23 That you trust. Yeah,

Francesca D’Alessio 22:24 Yeah, absolutely. And who speak the same language, you know, your work is so your public work. I mean, all of your work is so interesting, but the public work is so interesting, the way it interacts with the environment. You know, I mean, do you study the sun? Or how do you I mean, a Moray pattern, where does one learn to make that and the way that you play with shadow and, you know, using these natural elements to create these incredible experiences, it's, it's profound, really,

Catherine Wagner 22:50 I always start with kind of doing an in depth tour of the site, the one with the Moray patterns that was up in Seattle. And it came from an idea I had in the hotel room, because the rain was so strong, and it was just pouring down and the winds came up. And at one point, I looked at the hotel room, and the rain had gone from vertical to horizontal. And I thought, Oh, my God, that's, that's intense. And so I made these just photographs out the window of this horizontal rain. And the more I looked at it, it started really looking like a Moray pattern. And so I thought, what if I was to transfer these horizontal rain patterns to an algorithmic pattern, and work with an algorithm of these rain patterns? And then when you offset them just ever so slightly, that's what creates the Moray

Francesca D’Alessio 23:37 How beautiful. There's something is so brave. I don't know if that's the right word, but to be on the site and not know what you're going to do until the site speaks to you. I mean, there's something that's like almost fearless,

Catherine Wagner 23:50 It's called anxiety.

Francesca D’Alessio 23:53 You're very cool, calm, collected.

Catherine Wagner 23:56 It sounds, it sounds like kind of poetic now. But when I'm in those periods of like, conceiving of ideas, I'm in like kind of a hyper creative place that ideas are kind of zigging and zagging and moving and but I'm in this just incredibly anxious place, because there's just so much to kind of like, understand. And then as I as I begin to kind of like, put things together, the anxiety comes down. And I can kind of think more fluidly about what this might look like.

Francesca D’Alessio 24:27 It's amazing, because I'm listening to the story. And I'm wondering, like, would I have, you know, really taken account of the rain that way. And I think there's something beautiful about your spirit that you notice these subtleties that then become what that site really means. There's something very spiritual and beautiful about your process.

Catherine Wagner 24:45 I often will hire a historian or algorithmic designer because I don't know how to do all these things. So but in kind of like working with engineers and algorithms, designers and historians, there's just kind of a wonderful collaboration and when the Human Genome Project was going on. And we were trying to map the genome of ourselves, I was so intrigued with how genetics would change or construct culture and like kind of the miracles and the madness of what genetics can do, and kind of the ethics and the social implications of genetics. I was really struck with that. And I was like, wow, this is changing the way we will live. And so I immediately started reading all I could about genetics, and I have absolutely no background in science at all. And realized this is the miracles and the madness of culture of what genetics can do in terms of constructing culture, saving lives. But what are we going to do with this in whose hands will this information be? And so I, I wrote a fellowship to both the Science Foundation and to an arts foundation received them both. And then I found myself embedded in the seven sides of the Human Genome Project for five years. And so there I was around all these Nobel scientists, and I was working alongside of them. And we ended up having these incredible conversations and recognize that in many ways, we are climbing a similar mountain, albeit choosing different paths, I think the life of the mind is something that that takes me into places that have become very much part and parcel with my art making process.

Francesca D’Alessio 26:19 It's such a beautiful thing. I love that you're in these situations, I love that you're there amongst, you know, prize winning scientists. I mean, I think an artist needs to be in all of these spaces. I'm sure they learned so much from you, probably more than you realized.

Catherine Wagner 26:33 We ended up having some profound conversations. And you know, I had to kind of get over myself, I almost told him, you know, I have no science background, I said, the only thing I ever did was take human sexuality because it was a, you can do that instead of a biology class. And I got an A, you know, but there was something about that, and it was the catalyst for me to start thinking about public work. I think a lot of times I tackle projects that I don't know anything about, but that I'm so intrigued with the way I know, it impacts culture, that I feel like it's almost my duty. That's how I learn. And I as I said, for me thinking as a sensual pleasure.

Francesca D’Alessio 27:11 When it's so wonderful, because as you learn you interpret it and then communicated out to the rest of us, you know, through a different through a different language. What is what is next you have any ideas of outside museum?

Catherine Wagner 27:23 Well, I'm working on a project right now for a new airport in Tampa, Florida. And it's 32 feet high by 29 feet wide. And there's 120 etched aluminum tiles. And in order to make this wing of the Tampa airport, they had to destroy a very famous garden that used to be at the airport, it was a modernist garden, and they had to take it out in order to open this new international wing. And so in learning about that story, I thought the gardens gone, but maybe I could bring back a part of that garden through an artwork. So it's done in this laser etched, custom colored anodized aluminum that takes on this kind of undulating form, you can see it on four different levels of the museum. So you can actually you have these varying points of view, so you'll get pieces of it. Or if you stand at the bottom and look up, you can see the whole thing. But it's an amalgam of all the difference of indigenous tropical plants to that area in Florida. And so it's kind of like a magic realism of this cacophonous garden that now is 32 feet high to give this other image of a garden that had to go.

Francesca D’Alessio 28:32 Wow, I love that you brought it back. It's I like your sentiment on all of these projects. And tell me about prisons, because you do a lot of interesting cool work with light and sunlight and prism.

Catherine Wagner 28:45 I love to work with light I love to work with. I mean, it's was interesting that you asked, I have worked with these other prisms, I did a museum show called archaeology in reverse. And I had constructed an entire with these different colored acrylics in a very elaborate museum. And I had done an installation there. And I was just so intrigued with the engineering of just all these cacophonous struts. And then I thought nobody ever will see this because nobody's allowed up here. What could we do so that people could see this installation that's above the skylights? I thought periscopes that's how we'll do it. And the periscopes came from an idea I tried to work within in LA for the city of Santa Monica. So I kept that in my back pocket. And the piece I ended up doing for Santa Monica was a 36 foot ellipse with LEDs. And it was under a sky bridge that everybody entered, and only the people who had market rate housing had access to the ocean visually. So I thought what can I do to bring the ocean to everybody. So I found out that they have the buoys out there and you can tie into them. And they'll always give you a reading of what's happening atmospherically in the bay. So we did that and then this 36 foot ellipse under a sky bridge. It's giving a constant readout of atmospherically what's happening in the ocean. And so anybody who walks in there can get this can get a sense of the ocean. But then I put a thermal camera with a 12 foot wide radius, so that anybody who walks under that just the heat from their body is now being recorded. So now they're part of that ocean landscape. And whatever movement they make, whether they lie on the ground and make a snow angel, or they've got dogs and kids running around, you're seeing the pattern of the ocean. And then you're seeing these much hotter white spots, kind of moving throughout that pattern. And that was to kind of bring this sense that you are a part of this landscape, you have access to this ocean. So I think in many ways, I try to make things that are beautiful, so that people want to engage with them. But then these interactive components are kind of, you know, kind of another gift that happens.

Francesca D’Alessio 30:58 I'm sure it's so well loved. I'm sure there's people waiting for it to be turned on to show folks visiting to you know, it's probably such a big part of their community.

Catherine Wagner 31:06 Yeah, well, it's the entrance to this to this community. So that was kind of a fun, interactive project to do.

Francesca D’Alessio 31:11 So are there any movements or artists or anyone that you're following right now that helps inspire you?

Catherine Wagner 31:18 Oh, god, there's so many people making such great work and contributing in so many ways, this whole art world, it's like, there's not one person who's like this, this is the person who's leading the way. There's a big pie, it's a giant pie, and the pie keeps getting bigger. And I feel honored to be maybe a slice of that pie to, you know, make my contribution be one slice of the pie. But I think Theaster Gates is doing just amazing things in terms of community. I think he also has an incredible practice in terms of an object maker as well. And so I'm very interested in people who can straddle that the object making of their personal work that goes into museums, etc. And then the work that integrally involved with community and how community gets this kind of awakening and this other idea from that work.

Francesca D’Alessio 32:21 Next time you're in the city take a moment to look up. Catherine reminds us to take a moment to appreciate nature's beauty. Trace the patterns of the clouds, notice its movements creating choreography in the sky. Art is everywhere. And that unique approach that Catherine takes when drumming up inspiration from her works is absolutely fascinating. Please join us next week when I have the pleasure of speaking with the wonderful Tahirah Rasheed and Angela Hennessy, co-founders of the collective See Black Womxn an esteemed group of artists, activists and writers raised on black feminist theory, who are on the frontlines to increase visibility and create a community of support for self-representation and creativity for black women. I'm Francesca D'Alessio and I oversee the public programs initiatives here at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. And I'm your host for this series. Please visit our website deYoung.FAMSF.org/programs/localvoices to find the transcripts for this episode. And to be sure to subscribe to the museum's email newsletters to learn all about what's going on here at the de Young.

Hear from Catherine Wagner, a conceptual multidisciplinary artist, whose process emphasizes investigation and deep appreciation for science. Learn more about Wagner’s practice, collaborations, and site-specific installations all across the Bay Area and the world.

Over the course of her career, Catherine Wagner has been observing the built environment as a metaphor for how we construct our cultural identities. In 2001, Ms. Wagner was named one of Time Magazine’s Fine Arts Innovators of the Year. Her work is represented in major collections such as the de Young museum, LACMA, SFMoMA, The Whitney Museum, MoMA, among others.

Learn more about Catherine Wagner and her upcoming projects.

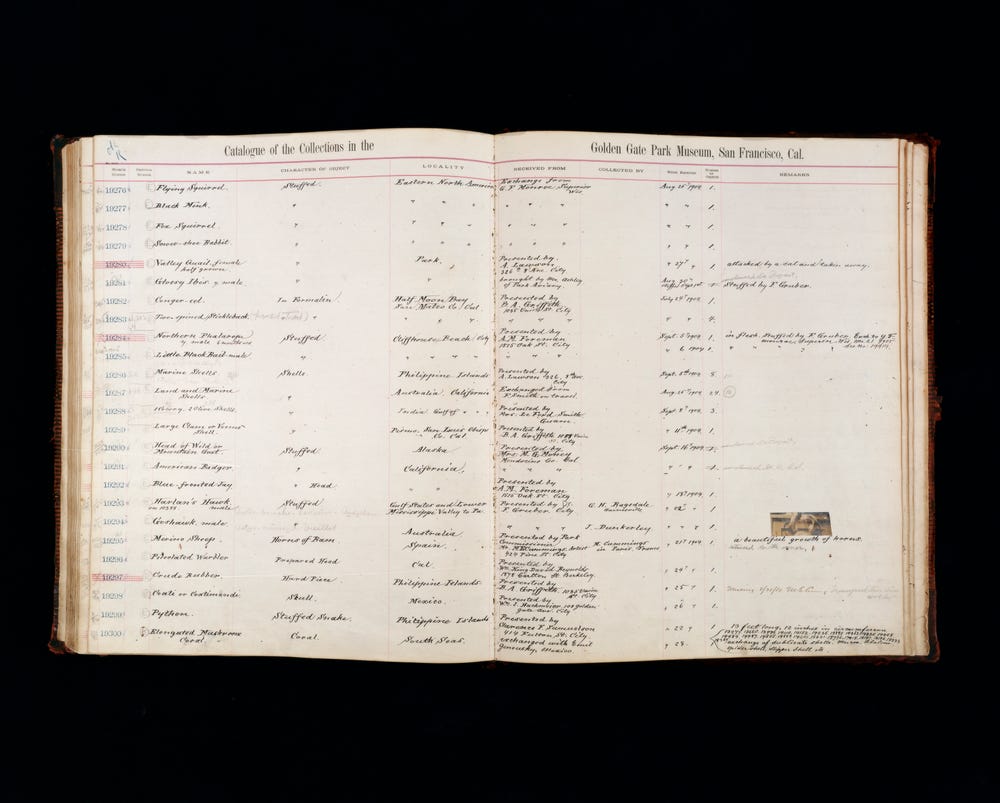

Wagner, Registars Ledger (Text Page #6) 20 x 24 in,1999.

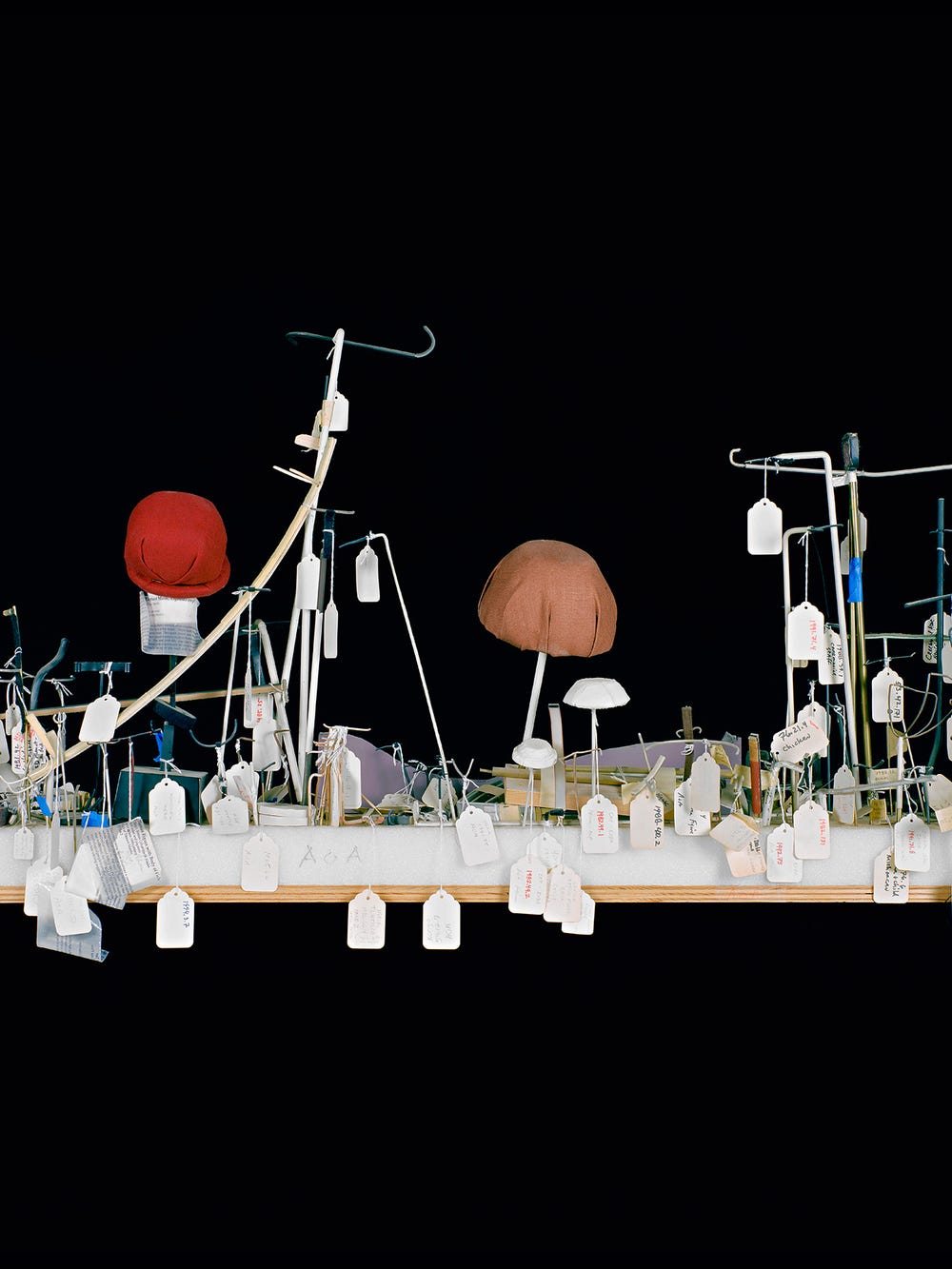

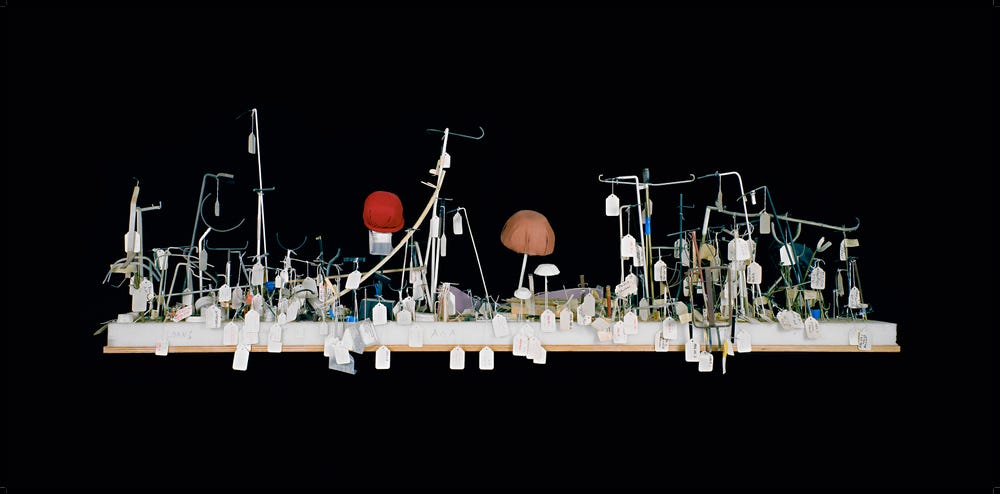

Wagner, ReClassifying History install at de Young, 2005.

Wagner, Columbus Penelope Delilah, 49.5 x 69 in , 2005.

Wagner, Ship II, 40 x 60 in. 1999.

About Local Voices

Local Voices is a new podcast series from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco designed to celebrate art and Bay Area creativity. Local Voices highlights unique perspectives from Bay Area visual artists, musicians, scholars, community leaders, and thinkers aimed to reframe exhibitions and collections through relevant and local narratives. Through these diverse access points, we welcome the Bay Area community and beyond to engage in meaningful and inspiring narratives.