Q+A: Making Lhola Amira an Exhibition for All

By Magnolia Molcan, in conversation with Natasha Becker and Karen Berniker

December 15, 2022

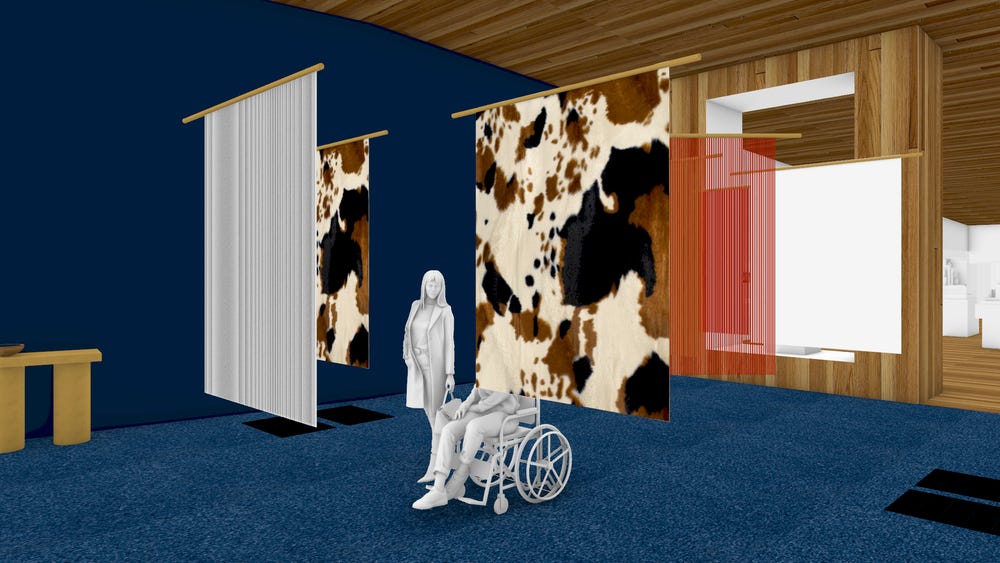

Design rendering for Lhola Amira: Facing the Future at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Lhola Amira: Facing the Future is the first in a series of exhibitions that interpret the arts of Africa through the eyes of contemporary artists. I spoke with Natasha Becker, curator of African art, and Karen Berniker, access programs manager, about how the exhibition was designed with accessibility in mind.

Magnolia Molcan: Natasha, can you give a brief overview of the exhibition?

Natasha Becker: Lhola Amira: Facing the Future centers art from Africa as a site of critical exploration for the evolving nature of African culture. Lhola Amira, a South African artist, is offering visitors ways of becoming more open and more sensitized to the pain of others, and the possibilities of the present. THEY have envisioned a new sacred portal called Philisa: Zinza Mphefumlo Wami (2022), which translates to “Let It Be Healed: Be Steady My Breath, My Spirit.”

The Philisa supports individual and collective health by opening up a space between past and future, between what was and what is to come, between the in breath and the out breath, between earth and sky, between dusk and dawn.

Because “the now” is interconnected with the past and the future, the Philisa is a waiting area, a threshold, between one point in time / space and the next. Visitors are invited to enter this space, where they are supported through sound, beadwork created by women’s beading circles, and gestures (such as salt and light) toward the cleansing of wounds.

Artworks from the permanent collection are placed in conversation with Amira’s work, exploring the themes of wounding and healing. These diverse selections of 19th and 20th century art from Africa include sculptures and ceremonial pieces made for rituals supporting and generating healthy human and ecological relationships. They reflect different worldviews about the interconnectedness of individuals and communities, ancestors and descendants, earth and ocean, physical and spiritual worlds.

MM: Karen, how did you get involved in the project?

Karen Berniker: I got involved by invitation of Natasha. She had been informed that I am typically invited to installation team meetings. Also, Lhola Amira was going to be at the de Young for more than three months, so we needed to make sure it was going to be ADA compliant.

Once I heard that there was going to be salt on the floors and beads hanging from the ceiling, immediately I became very concerned. I thought, OK, we need to think about people who use wheelchairs. We need to think about people who use white canes. How can a person who uses a wheelchair wheel into the installation? Natasha was very receptive and said that she was going to have another conversation with the artist to see what they could do to make it accessible to people with disabilities. The artist was really gracious and looked at this challenge as an opportunity to really rethink THEIR whole project.

MM: How is the Philisa in this exhibition different from Lhola Amira’s previous Philisa?

Installation of Lhola Amira at SMAC Jhb 2019. Image courtesy of SMAC Gallery, copyright Lhola Amira

NB: Typically, Amira’s Philisa are circular, beaded portals that hang almost to the ground, and they usually hover over a circular bed of salt on the floor. All have a sound element. This presents a challenge to a person in a wheelchair because the strings of beadwork could get stuck in the wheels of the chair, and they might not be able to put their feet on the salt.

In the new Philisa, the circular structure has given way to individual beaded and fabric panels; they hang like curtains floating in a breeze. Their height has been adjusted so that they gently touch the heads and shoulders of all visitors. The salt is in a special ceremonial bowl placed on a table accessible to all. The artist also reconfigured the light and water sources for the exhibition so that they activate the entire gallery instead of only the area around the Philisa.

KB: What’s nice is that there’s going to be a bowl that has the salt. This way people can feel with their hands, as opposed to walking on it barefoot. We’re able to provide equal opportunity of accessibility by doing it this way.

MM: How else was the exhibition designed with accessibility in mind?

NB: Amira creates melodic soundscapes from traditional instruments or vocalized sound in THEIR Philisa and films. Captioning is provided for both. Our gallery wall text is in large format, and we also produced a booklet with large-format fonts to describe the Philisa and the film.

KB: Last but not least, we needed to make sure that the panels that hang from the ceiling, which have writing and poetry on them, were four feet apart. This is so somebody can wheel through them and read the writing on the panels.

Installation view of Lhola Amira: Facing the Future, de Young, San Francisco, 2022. Photography by Jorge Bachmann,

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

MM: How do you work across teams to make sure exhibitions, including this one, are accessible?

KB: Facilities and access teams work closely together. We go hand in hand because the facilities team is always thinking about safety, and I’m always thinking about disability. We want to make sure that not only is it a safe environment for all people, but that it’s accessible for people with disabilities as well.

Typically we only focus on accessibility for special exhibitions, any exhibition that’s going to be on the premises for more than three months. We need to ensure that they’re ADA compliant; it is part of what the law says about a public facility. This was a really unique project because it’s an installation in the museum that’s going to be there for a whole year.

MM: How receptive was the artist to incorporating accessibility into the project?

NB: Rather than just “incorporate accessibility” into THEIR Philisa, THEY felt called to actually recreate the Philisa. THEY rejected the idea of modifying and asked that we allow THEM the time and space to meditate on the work THEY are being called to do for all. Amira’s work is addressed to all people, including those with health conditions or impairments. Everyone can benefit from deepening our state of connection, slowing down, leaning into the unknown, and moving with what is alive.

MM: Beyond physical accessibility, there are often other barriers to making museums accessible to the public. Natasha, you’ve talked about demystifying what people are looking at in this exhibition. Can you speak to that a bit more?

NB: Amira’s Constellation (elements and objects the artist has brought together) is profoundly experiential and complex. It’s important to offer visitors an understanding of the ideas, practices, and symbolism of what they are experiencing. Fortunately, we have a whole year to unpack the exhibition. And we are excited to begin this journey at the exhibition opening through a conversation with the artist.

MM: Are there takeaways from this exhibition that will inform how you approach future exhibitions?

KB: Yes. One idea that we’ve come up with is enhanced audio descriptions for people with low vision. How great would it be to use the artist’s voice as part of the audio tour, so they are actually doing the enhanced audio description? I don’t think it’s going to come to fruition for this project because the opening is so soon, and the idea only occurred to us a few weeks ago. But, for contemporary artists, this is something that we should really think about doing moving forward.

Another takeaway is the fact that, if you work proactively with an artist, you can create an accessible exhibition. I think the artist deserves so much credit and recognition for the fact that THEY really had an original understanding of how THEY wanted THEIR project to turn out. Along the way, THEY were being told, “Sorry, this is a challenge for accessibility. That is a challenge for accessibility.” And THEY ended up embracing it and incorporating it into THEIR vision. So I’m very curious to see what the end result is going to look like.

NB: Absolutely. We want to engage everyone, and it’s important to constantly improve on exhibitions to allow everyone’s full participation and inclusion.

MM: Is there anything else you’d like to share about accessibility and this exhibition?

KB: I think that this exhibition will become the standard of what the expectation is for curators and exhibition managers moving forward. I’ve done some trainings recently with the curatorial team and exhibitions team all about accessible design within exhibitions. And this is a model representation of what an accessible exhibition ideally should look like. I think that the communication between curator and artist is so important in terms of making that happen.

NB: I was fortunate to work with Karen on the exhibition. Myself and the artist would like to express our gratitude for the care and guidance she brought to the process.

Interview by Magnolia Molcan, web managing editor, with Natasha Becker, curator of African art, and Karen Berniker, access programs manager. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.