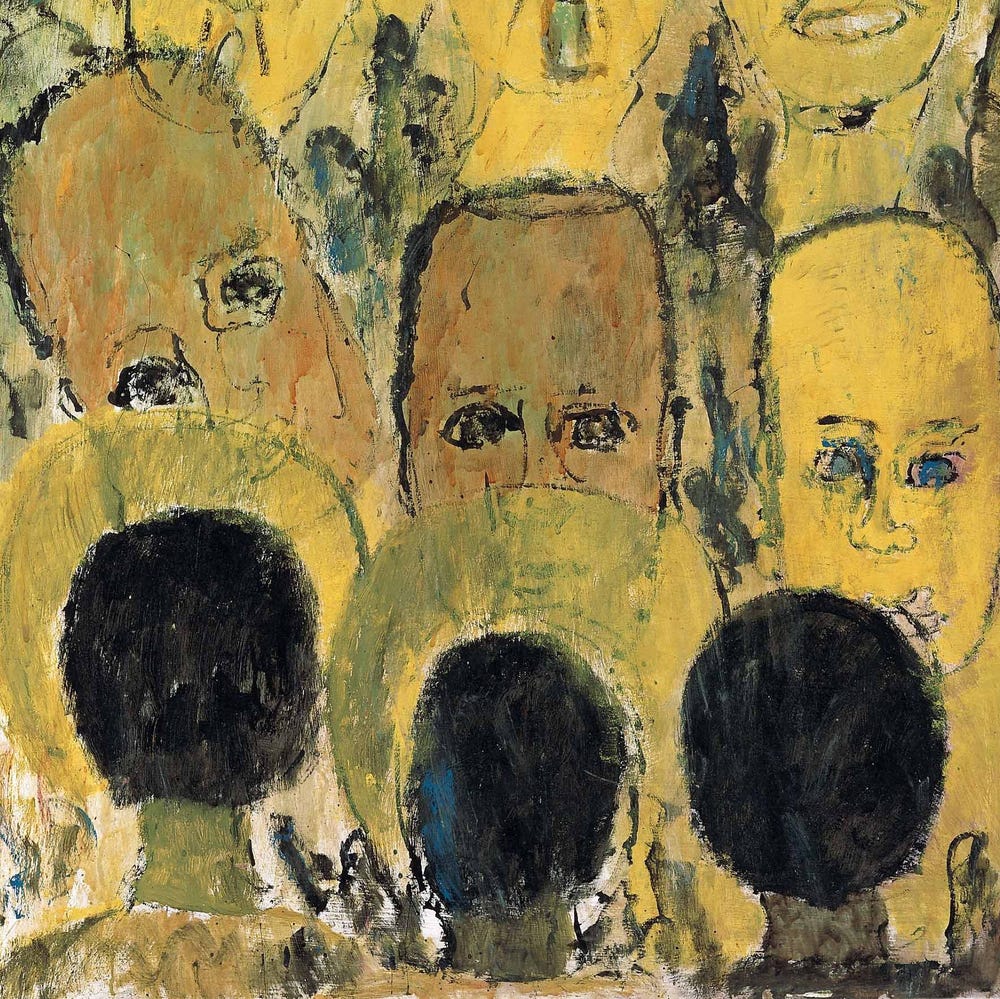

Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977). The Death of Hyacinth (Ndey Buri Mboup) (detail), 2022. Oil on canvas, 93 9/16 x 144 3/16 in. (237.7 x 366.2 cm). Framed: 104 5/8 x 155 3/16 x 3 15/16 in. (265.7 x 394.2 x 10 cm). © Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Galerie Templon, Paris. Photo: Ugo Carmeni.

Porcelain bodies lay stretched on the ground, lifeless, yet powerful. Glorified through art, we see martyrs’ persecution, suffering, and death, but also their advocacy and championing of challenged beliefs. The same can be said about the murders of Oscar Grant, Michael Brown, and George Floyd, as well as the image of Damar Hamlin’s lifeless body. Most recently, we saw images of Tyre Nichols, a Black man, beaten to death by five officers less than 100 yards away from his mother’s home. Caught on body cameras, Mr. Nichols’s body slumped over from the pain. Although lifeless Black bodies as the result of police brutality have become the norm, this was different — this was at the hands of Black officers, showcasing just how rooted white supremacy is within law enforcement. Black lives are continually lost due to state-sanctioned violence; this is the precipice of Kehinde Wiley’s newest exhibition.

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco describe Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence as “the senseless deaths of men and women around the world . . . transformed into a powerful elegy of resistance.” This exhibition showcases Wiley’s work under the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, the murder of George Floyd, and the resulting Black Lives Matter movement — arguably the largest movement in the country’s history. In the summer of allyship, as I describe the racial reckoning of 2020, conversations were had at home and in the workplace about how Black people were being treated in America, prompting overwhelming displays of advocacy rooted in being anti-racist and dismantling white supremacy. Today, even with continuous displays of systemic racism and oppression of Black communities, anti-racism and dismantling white supremacy are no longer the priorities. Places of advocacy and awareness have been replaced by the reactive excitement and entertainment of the news cycle telling stories about continued systemic violence. Wiley’s interpretations of Black life and death remind us again of the importance of Black lives.

Kehinde Wiley, Femme Piquée par un Serpent (Mamadou Gueye), 2022. Oil on canvas, 131 7/8 x 300 in. (335 x 762 cm), framed: 143 5/16 x 311 x 3 15/16 in. (364 x 790 x 10 cm). EX1137.2. ©️ Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Galerie Templon, Paris. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Wiley’s artwork is revered around the world; he even painted a world leader with his (in)famous Barack Obama portrait. Known for using symbolism and formats traditionally held for white people in positions of power and privilege, Wiley portrays Black men and women with rich, dark skin tones exuding the same amount of power and importance as the subjects in paintings and sculptures of the past. Wiley is known for referencing the work of “old master” artists. Old master refers to a renowned European painter or artwork prior to the 1800s. These works ranged from paintings to sculptures of and by white people who were wealthy or had access to wealth. Power dynamics played a large role, as art was either commissed or purchased by royalty, landowners, merchants, and statesmen. Rarely seen were images of Black people, as they were enslaved or servants, left invisible in most works or visible only in the background. It’s ironic that Wiley’s transformative work honoring wounded or dead Black people originates from a term like old master. It is impossible to view Wiley’s pieces without feeling the impact of enslavement of African and Black people in this country.

By placing Black bodies in positions reminiscent of old master works, Wiley is liberating Black people. With each stroke of paint, he reclaims the power Black people once had. “By inscribing Black bodies into known examples of Western painting and sculpture, Wiley counters the historical erasure of people of color from the dominant cultural narratives,” says Claudia Schmuckli, curator in charge of contemporary art and programming. This collection is the story of systemic oppression, in which these Black bodies endure while others are lost.

“That is the archaeology I am unearthing: the specter of police violence and state control over the bodies of young Black and Brown people all over the world,” says Wiley. In 2022, police killed 1,176 people, making it the deadliest year on record; Black people made up 24% of those murdered by police, but only 13% of the US population. Police violence is both the deadly outcome and the reminder of the fact that Black life is not valued. State control speaks to the systemic inequality supported by structural racism and systemic oppression that has limited the advancement and opportunities of Black people. State control is a form of power over Black people. A pillar of white supremacy is power. One way to capture that power is to have representation through art. Old master art, depicting everything from martyrs to royalty to everyday life, conditioned society to see white people as the norm.

Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977), Youth Mourning (El Hadji Malick Gueye), After George Clausen, 1916, 2021. Bronze, 14 3/16 x 16 9/16 x 31 7/8 in., 136.69 lb. (36 x 42 x 81 cm, 62 kg), base: 35 7/16 x 25 9/16 x 40 3/8 in. (90 x 65 x 102.5 cm). © Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Galerie Templon, Paris. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Wiley paints the outcomes of white supremacy. He sculpts images of death and resilience. Youth Mourning (1916), a classic by George Clausen, depicts his daughter's pain from losing her fiance in World War I — naked and balled up, her stark white skin before a wooden cross. I think of Black mothers who ball themselves up tight to stop the pain from entering their hearts when police murder their children. Wiley, inspired by Clausen, used the same pose in his Youth Mourning (El Hadji Malick Gueye), After George Clausen, 1916 (2021) to show the pain of death. The bronze sculpture displays the reality of Black youth experiencing death and harm on a continuous track. Black people don’t have the privilege of focusing on a single crisis, like the Ukraine war; we have to contend with state-sanctioned violence, environmental racism, infant mortality, food deserts, biased healthcare, inadequate schools . . . the list goes on and on.

Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977), The Virgin Martyr Cecilia (Ndey Buri), 2021. Bronze, 9 5/8 x 19 1/8 x 41 5/8 in., 130.07 lb. (24.4 x 48.5 x 105.8 cm, 59 kg), base: 35 7/16 x 28 3/4 x 51 3/16 in. (90 x 73 x 130 cm)., © Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Galerie Templon, Paris. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Why does it take a lifeless body for a Black person to be seen? Why did it take the killing of Oscar Grant to start the conversation of law enforcement training? Why did it take Michael Brown being murdered by police with his hands in the air for people to pay attention to the long and tenured history of racism and police violence in Ferguson, Missouri? Why did it take repeated imagery of a knee on the neck of George Floyd to cause international outrage that reginited the call for Black Lives Matter? Why did it take seeing Damar Hamlin’s lifeless body on a National Football League field to value his nonprofit GoFundMe toy drive, which asked for $2,500 but is now at $9 million and counting?

The beauty and value of art is how you interpret it, but what if you were called to see the value in Black people, in death and life. Black imagery in America is synonymous with death, pain, and resilience. An Archaeology of Silence celebrates how those who remain carry the legacy of those who have gone. The way you view Wiley’s work speaks to where you are in your anti-racism journey. Wiley demonstrates the value of and to those at risk of death or harm caused by the systems that benefit white people over Black people.

As a white person, you may be asking yourself, what do I do? I encourage you to take action. Supporting Wiley’s art provides a pathway for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco to continually work with Black artists to tell our stories. Let them know you want more. Attend one of the activations or find a resource from An Archaeology of Silence in the Piazzoni Murals Room (PMR) to continue to learn and unlearn. But most important, take some time to reflect and acknowledge the privilege you have to see Wiley’s work for the details, colors, and powerful imagery, rather than the value of your life.

Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977), The Death of Hyacinth (Ndey Buri Mboup), 2022. Oil on canvas, 93 9/16 x 144 3/16 in. (237.7 x 366.2 cm); framed: 104 5/8 x 155 3/16 x 3 15/16 in. (265.7 x 394.2 x 10 cm). © Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Galerie Templon, Paris. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Black people, you have the opportunity to reclaim and affirm your existence. You can celebrate in the space Wiley has provided for you to be seen. Take the time to value yourself in the PMR by reflecting on those you’ve lost and the excessive state violence you endure, and recharge for what is to come. See yourself in his work. I see myself in Wiley’s work. I see full lips, curly hair, sneakers, jeans, braids, and hoodies. I see the richest skin tones, from soft caramel to melted dark chocolate. I see how I am powerful and valued. Amongst systemic oppression and white supremacy, Black people may feel lost and forgotten. But Wiley reclaims what Black people originally possessed: our martyrs, our royalty, and our everyday lives.

Text by Dr. Akilah Cadet, founder and CEO of Change Cadet.