Grandeur and Serenity: Mallinson’s “National Parks” Textile Series

By Laura L. Camerlengo, in conversation with Madelyn Shaw and Michael Fehr

July 16, 2021

The natural world has long been a source of inspiration to textile designers. This fall, the de Young museum will explore the legacy of this tradition in To Teach and Inspire: The Julia Brenner Textile Collection. This textile, manufactured by H. R. Mallinson & Co., is a highlight of the presentation. Here, we explore the textile’s rich history — and its ecological inspirations — in depth with experts Madelyn Shaw and Michael E. Fehr. Shaw is a curator, author, and speaker whose research explores the history of textiles and dress with a focus on American manufacturing and its global connections. She is the former curator of textiles, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Michael Fehr has been an interpretive ranger since 2016, working in parks from coast to coast, and he enjoys opportunities to help visitors from around the world form connections to these places. He is currently a park ranger, interpretation, at Mount Rainier National Park.

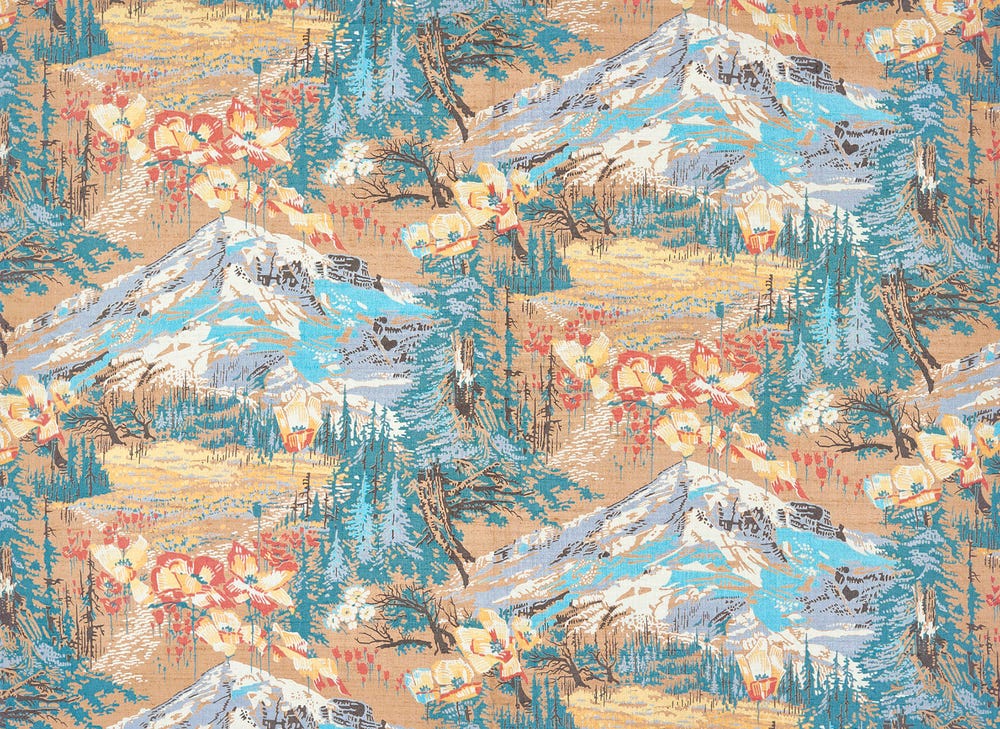

Dress fragment: Paradise Valley, Mount Rainier, 1927. Manufactured by H. R. Mallinson & Co. Inc., designed by Walter Mitschke. Silk, complex weave, cylinder printed. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, gift of Mrs. Gustave Brenner, 55237.7

LLC: Madelyn, H. R. Mallinson & Co. produced this textile, and at the time of its manufacture, Mallinson & Co. was a leading silk manufacturer in the United States. How did H. R. Mallinson & Co. come to such prominence?

MS: The company was founded in about 1896 by M. C. Migel, who had been a salesperson for a Paterson, New Jersey, silk manufacturer. He took H. R. Mallinson into partnership, and when Migel retired, in late 1912, Mallinson became the president of the firm. He changed the company name from M. C. Migel & Co. to his own in 1915. Both Migel and Mallinson were experienced salespersons, and they approached the silk business from the point of view of the consumer: What did customers want? How best can we give it to them? And how can we achieve profitability and stability? My short answer to these questions is “Attention to detail.” The firm created high-quality silk fabrics that would wear well, with interesting and inventive designs, and marketed them through publicity campaigns that drew on all the available media of the period. They positioned the firm from the beginning as on a par with the best European silks; consumers then, as often now, assumed that high-end European goods were better made and more fashionable than American made. Mallinson’s priced their silks in line with that business philosophy, but their design philosophy ensured that while a well-to-do woman might have her dressmaker create a new dress from three or four yards of one of their exclusive designs, a shop girl could also buy a yard and make herself a blouse or scarf. The design studio ensured that every taste — from the most conservative to the most avant-garde — could find something to like, in every line, every season.

LLC: What prompted H. R. Mallinson & Co. to produce this design, which was part of their “National Parks” series?

MS: In 1921 E. Irving Hanson, who was the vice president and head of the design department, visited several national parks on a western US trip with his family. The National Park Service (NPS) was then pretty new, only formally designated as such by the Federal Government in 1916. So, looking ahead, as designers routinely do for inspiration, they brought out the “National Parks” series in 1926, for the tenth anniversary of the park service’s founding. I suspect that Mallinson’s was influenced also by the fact that a competitor, the Stehli Silk Corporation, introduced a series in 1925 called “Americana Silks.” These were taken from designs by artists and illustrators and [were] very topical, very “Jazz Age” in style. Mallinson had used American ideas in designs before 1926 — the hugely successful “Mexixe” line in 1914 and the “State Flower” series in 1915, for example — but the Stehli series was very well received. It is likely that Mallinson’s wanted to capitalize on that bandwagon but position themselves differently. In Mallinson’s business, the company name was the guarantee of good design and quality; they only once or twice gave a designer credit in print or asked an artist to design for them.

Courtesy of NPS/Michael Fehr

Courtesy of NPS/Michael Fehr

LLC: Michael, could you tell us about the ecology of the park? What notable landscapes does the design capture?

MF: It looks like the textile is showing the subalpine meadows in the Paradise area, likely in the fall given the coloration. The subalpine zone extends generally from 5,000 feet to 7,000 feet in elevation and is characterized by tree clumps interspersed with open meadows. The Paradise area is largely made up of heather, bell-heather, and huckleberry communities, which are predominantly dense, low-growing shrubs. They turn vibrant reds and oranges in the fall and rival the wildflowers in beauty in my opinion. The Paradise area also features the Sitka valerian and showy sedge communities, which give us many of our more varied wildflowers. I’ve been trying to identify the wildflowers depicted in the foreground of the mountain. The smallest red flowers appear to be a paintbrush (Castilleja genus), and the small white flowers are likely subalpine daisies (Erigeron genus). However, I haven’t been able to get an ID on the larger flowers with the distinctive red trim. Our best guess is that they are an artist’s interpretation. The photographs above show the Pinnacle Peak trail from the same perspective on the mountain, and then also a picture taken in the Paradise area that shows that wonderful fall coloration.

LLC: How would visitors — such as E. Irving Hanson — experienced Mount Rainier park in the 1920s?

MF: Automobile touring would have been the primary way visitors experienced the scenery seen in this tapestry in 1927. Mount Rainier was actually the first national park to permit automobiles to enter — in 1907. Early motorists were subject to an extensive set of regulations, including a speed limit of six mph. Women were permitted to drive inside the park beginning in 1916.

The road from the park entrance to Paradise Valley was begun in 1903 and completed in 1912, and was designed intentionally to both expose stunning views and to fit harmoniously with the natural landscape. Chief surveyor Eugene V. Ricksecker noted in 1904 that “the intention is to follow . . . the graceful curves of the natural surface . . . being most pleasing and far less destructive than regular curves laid with mathematical precision.” However, with the advent of automobile travel came an influx of visitation. By 1920 (only eight years after the road was completed), Stephen Mather, National Park Service director, remarked, “The present parking space for automobiles at Paradise Valley is wholly inadequate for the needs at this point.” The Park Service continues to strive to balance the needs associated with increasing visitation with our mission to preserve the places we steward.

LLC: Mount Rainier National Park has been cared for by indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Could you tell us about these communities?

MF: In terms of indigenous use of the land, the original stewards of what is now Mount Rainier National Park are the Cowlitz, Muckleshoot, Yakama, Nisqually, Puyallup, and Squaxin Island peoples and their ancestors. We know that people have been living in the valleys and plains within sight of the mountain for well over ten thousand years; however, for much of that time the lands now encompassed by the park were covered in ice and permanent snowpack. Indigenous land use of the subalpine slopes like those depicted in the tapestry is believed to date all the way back to the initial establishment of permanent plant and animal communities in those areas coinciding with the end of permanent snowpack (approximately 8,500 years ago). A place like Paradise Valley would likely have been home to seasonal encampments (year-round occupation being difficult given the heavy winter snowfall). These encampments would be used for the gathering of edible and medicinal plants and berries, bear grass and cedar bark collecting, and hunting of game. The National Park Service works with our tribal partners to continue traditional land usage and stewardship.

LLC: Madelyn, you have noted in earlier writings that both Hiram Mallinson and E. Irving Hanson traveled widely and had a deep respect for the natural world. Could you tell us more about their appreciation of the environment?

MS: In about 2004, I interviewed Mallinson’s granddaughter. Although her grandfather died when she was only about five, she remembered him taking her outside to marvel at the stars at his summer home in the Adirondacks. While the company was, of course, looking to sell silks, and thus always looking for new designs that would sell, and flowers are perennial favorites for dress fabrics, I think the fact that both men traveled regularly for both business and pleasure — to France, to Britain, to Egypt (Mallinson was an early invitee to view the tomb of Tutankhamen!), around the US, and to the Caribbean (Mallinson was a member of a yacht club in Havana, Cuba) — opened them to bringing their experiences of gardens and landscapes and the sea into the company’s work, rather than sticking only to what might be termed a “design by seed catalogue” approach. Mallinson was also emphatically self-educated; he left school at [age] ten to work in a department store as a cash boy. But the company’s designs, such as the series they did based on William Beebe’s exploratory voyage to the Galapagos Islands in 1925, suggest he possessed a wide-ranging curiosity that expressed itself in the silk designs.

LLC: How many colorways of “Paradise Valley” were produced? Was this typical of silks from the larger “National Parks” collection?

MS: I am not sure exactly how many colorways of this design were produced. The big series prints like this one often had as many as twelve different colorways for each design, and usually at least eight. The designs were also usually printed on three types of ground cloths, such as, for this series, a sheer (Mallinson’s Indestructible Voile), a textured weave (Mallinson’s Khaki Kool tussah silk), and the company’s most famous product, Pussy Willow taffeta. Each colorway usually involved eight colors—this added to the cost of printing and the complexity of the designer’s job.

(Left) H.R. Mallinson & Co. Lounging pajamas, ca. 1930. Silk, 2009.300.2653a, b. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Designated Purchase Fund, 1999. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Right) H.R. Mallinson & Co. Dress, 1929. Silk, 2016.327. Purchase, Funds from various donors, by exchange, 2016. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

H.R. Mallinson & Co. Dress, 1929. Silk, 2016.327. Purchase, Funds from various donors, by exchange, 2016. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

LLC: Who was the intended consumer for this textile? For what purpose would the textile have been used?

MS: Paradise Valley was a pretty conservative design, very realistic in its drawing, and quite a lush landscape. It might have appealed to a conservative dresser who wanted a little flare in her wardrobe, but in a bright colorway it might also have appealed to a Bright Young Thing! It is also a design that fills the textile — it is not a stripe, or a sparse or scattered layout. So, it would have suited almost any garment purpose: dresses, blouses, scarves, even a coat lining. Ready-made hat, handbag, and umbrella manufacturers used Mallinson designs for their products as well. Nineteen-twenties fashion, with its columnar silhouette, was well suited to these pictorial-type designs. The later 1920s and 1930s, which used more bias (diagonal) seaming, required designs that looked good even when interrupted by seams.

I think it is also important to remember that when this silk was created, ready-to-wear clothing was really just beginning to edge out custom-made. Many women still purchased their fabrics at a specialty or department store and had a dressmaker (of varying degrees of exclusiveness and price) cut and sew the garment — or they made it themselves! While some ready-to-wear manufacturers did use these silks in their lines, most of the dresses that survive appear to be dressmaker or homemade.

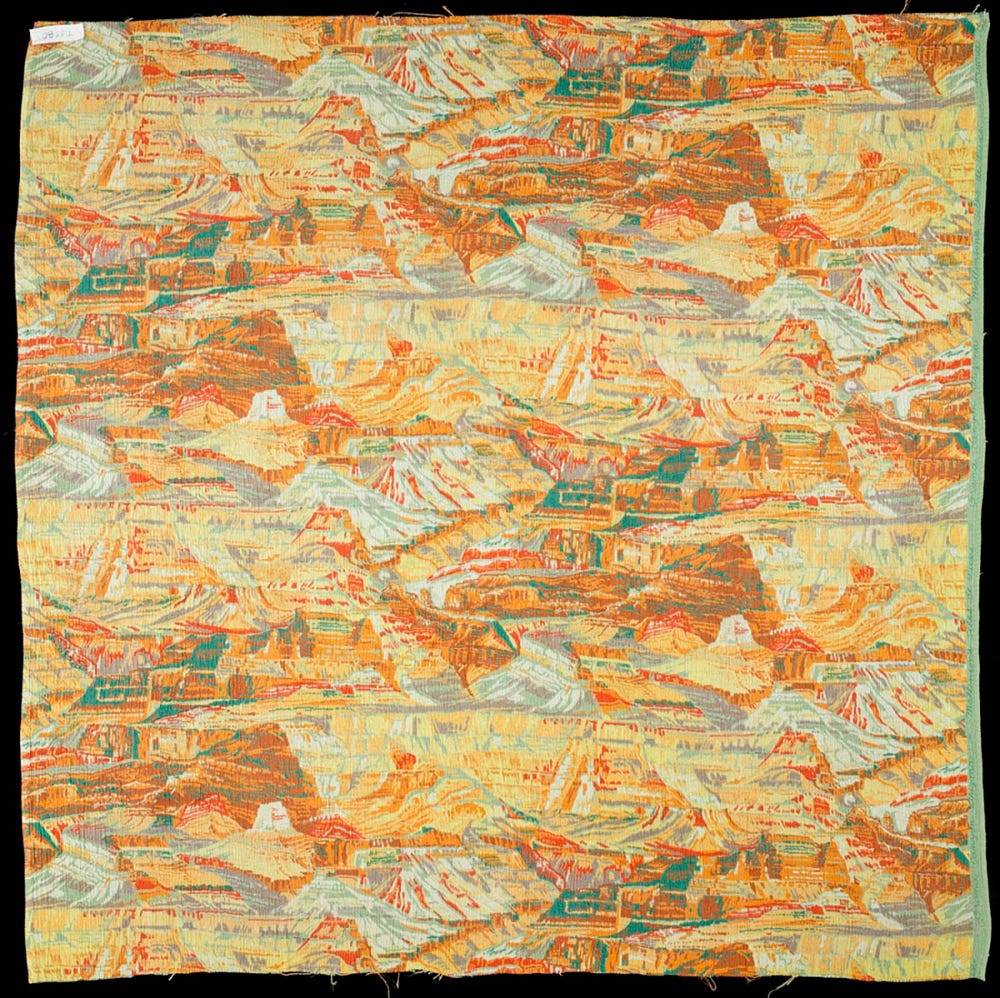

H. R. Mallinson & Co. Inc. Grand Canyon, 1927. Dress silk, 36 in. x 36 in. (91.44 cm x 91.44 cm). 95522. National Museum of American History, Smithsonian

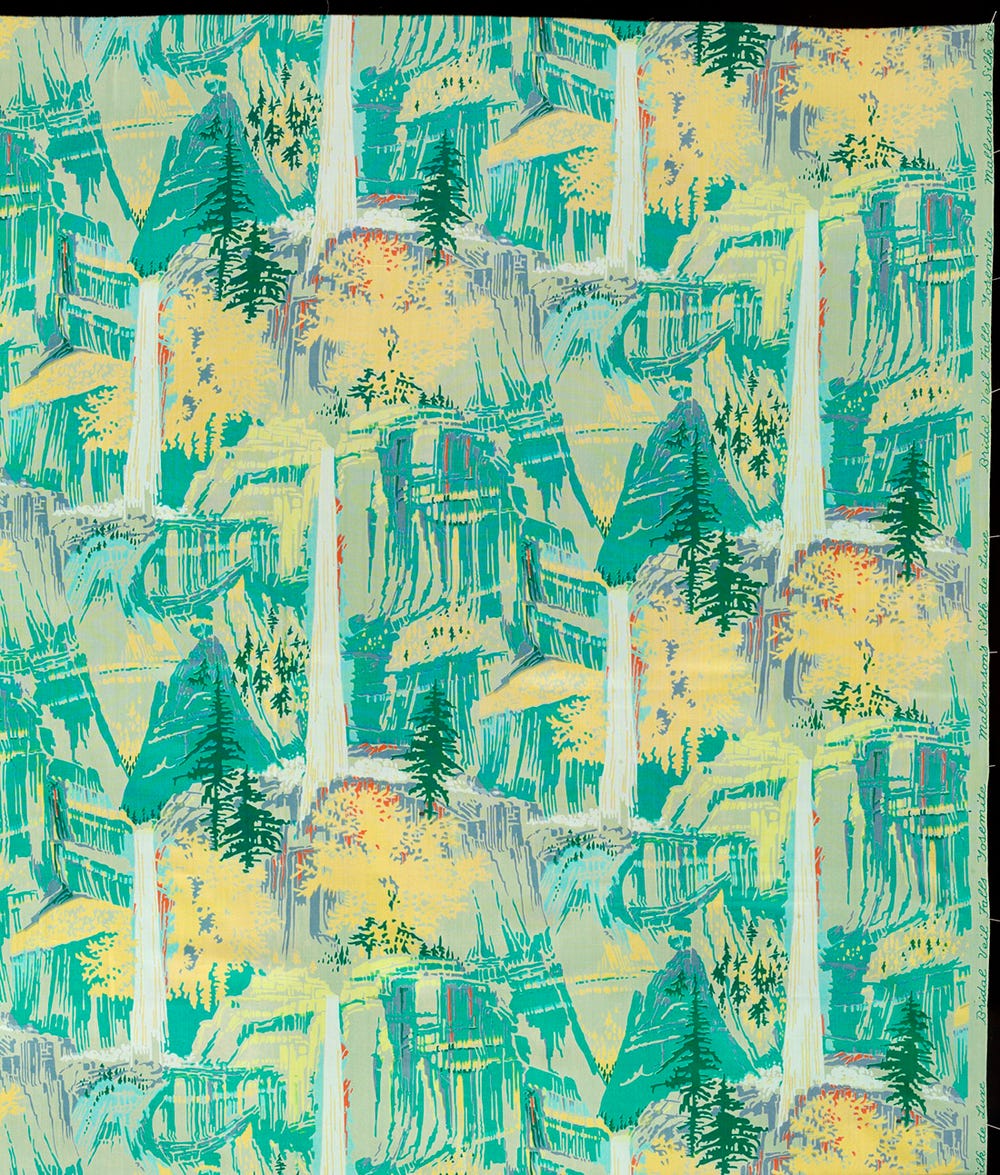

H. R. Mallinson & Co. Inc. Bridal Veil Falls, Yosemite, 1927. Silk, 36 in. x 40 in. (91.44 cm x 101.6 cm). 95522. National Museum of American History, Smithsonian

LLC: How was this series marketed or promoted by H. R. Mallinson & Co.? What aspects of the designs were emphasized in promotional literature?

MS: Mallinson’s adopted modern advertising practices and marketing techniques with the same clear vision that prompted its embrace of modern fibers, manufacturing methods, and aesthetics. Publicity, Mallinson believed, was the key to a strong business. His customers had to be told, and shown, that his silks were as good as imported silks.

The company sold its products wholesale to stores that sold yard goods, to the cutting-up trade for use in clothing and accessories, and, after the inauguration of its Upholstery and Decorative Fabrics department, to furniture manufacturers. Mallinson’s publicity campaigns targeted four market segments: individual consumers, buyers and salespeople for establishments that sold silk yard goods at retail, custom dressmakers, and the better grades of ready-to-wear manufacturers who purchased wholesale. The firm maintained that its direct advertising to the public made it easier for retailers to sell Mallinson goods, as consumers were conditioned to request Mallinson’s products by name. This “bottom up” philosophy motivated the company’s wholesale clients to carry or use Mallinson fabrics in the first place.

The company’s marketing arsenal included conventional print media such as newspaper and magazine advertisements, house publications, feature articles in newspapers, and what might be termed “outreach” media such as store window displays and fashion shows, and innovations such as exhibitions, contests, lectures, radio broadcasts, and even, at one point, a film. This particular series used all these except the film, as far as I know.

One thing I really like about the company’s marketing in this series is the fact that the “Blue Book” that was printed to accompany this series, which showed pictures of the designs and suggestions for how to use them, as well as pictures of the landscapes that inspired them, acknowledged the National Federation of Women’s Clubs as a mover and shaker in getting the National Park Service created. This has always seemed to me not only a smart marketing move, but a realistic understanding that women in the 1920s were not just well-mannered, beautifully dressed mannequins, but also active participants in the cultural, social, and political life of the nation. The designs themselves were chosen to show off the diversity of the American landscape, and both its grandeur and serenity

LLC: Our H. R. Mallinson textile was a gift of the company to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco through local textiles collector Julia Brenner in 1938. Was it common for Mallinson’s to give their textiles to collectors and museums in the 1930s? If so, what was their motivation?

MS: The Allentown Art Museum has many samples of Mallinson silks that were collected by Kate Fowler Merle-Smith. They are generally not full yard lengths, and I do not know if she bought them or requested them from the company. Mrs. Merle-Smith collected many different kinds of textiles (including samples of the Stehli Americana silks mentioned above), and her collection was the foundation of the department at the Allentown Art Museum. Mallinson did give a few samples of its work to the Metropolitan Museum. The Brooklyn Museum was given some wonderful pieces by a designer, I think Martha Ryther, but perhaps Hazel Burnham Slaughter — I can’t recall now. Several other museums have scattered examples. Unless we find the company name on a selvage or recognize one of the known designs, it’s impossible to tell how many more examples made of Mallinson silk might be hidden in fashion collections.

The bumper crop, so to speak, resides in the textile collection at the Smithsonian’s NMAH in Washington D.C. Back in the 1910s and into the 1930s, the curator there, Frederick Lewton, used to write to companies whose work he read about in the trade journals or newspapers and felt were being especially inventive or interesting and worthy of being highlighted in the Textile Hall at the old US National Museum. When Lewton sent you a letter asking for samples of your new line, you snapped to and shipped a box off by return of post! Textile manufacturing was one of the US’s biggest industries, and it touched millions. Having your products on display in the National Museum’s Textile Hall was a kind of seal of approval—this was the best that the US produced. Over the years the company gave about two hundred samples of its silks to the Smithsonian; database records for these can be searched (keywords “Mallinson” and “silk”) on the NMAH website, although many are not yet photographed. And many other important—and even some obscure — American textile companies are represented in the collection.

Interview conducted by Laura L. Camerlengo, associate curator, Costume and Textile Arts, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Learn more about To Teach and Inspire: The Julia Brenner Textile Collection.