In any discussion of the pre-war artistic milieu of Paris, there is no more acute observer than Marjorie Perloff, who has written extensively on La Prose du Transsibérien, Cubism, Futurism, and other avant-garde movements in both art and literature. This essay is excerpted from her 2008 Logan Lecture at the Legion of Honor. La Prose du Transsibérien is on display at the Legion of Honor from March 10–August 12, 2018.

Excerpt

La Prose du Transsibérien is a text full of contradictions. The title, for starters, is odd: it should be “le prose” and, even then, why call a lineated lyric “prose”? Cendrars declared that he used the word “prose” so as to open up the discourse; then, too, the poem is “dedicated to the musicians”—evidently those new musicians of the period, such as Eric Satie or Igor Stravinsky, who were avoiding all conventional rhythms. The long free-verse lines, with their paratactic structure and repetition, remind one of Walt Whitman, but the voice of this poem is hardly Whitman’s oracular one. Rather, Cendrars stresses immediacy, nervous energy, and excitement:

Back then I was still young

I was barely sixteen but my childhood memories were gone

I was 48,000 miles away from where I was born

I was in Moscow, city of a thousand bell towers and seven train stations

And the thousand and three towers and seven stations weren’t enough for me

Because I was such a hot and crazy teenager

That my heart was burning like the Temple of Ephesus or like Red Square in Moscow

At sunset

And my eyes were shining down those old roads

And I was already such a bad poet

That I didn’t know how to take it all the way.

(Ron Padgett, Trans.)

“Back then”—“En ce temps-là”—when was that exactly? And what does it mean not to be able to go all the way (“jusqu’au bout”)? Cendrars’s metaphors are extravagant: his heart burns like the Temple of Ephesus or like Red Square in Moscow; in the next section, “the Kremlin is like an immense Tartar cake / Iced with gold,” and so on. The poem’s journey is poised on the threshold between documentary realism and fantasy. Time and space are carefully specified: the poet boards the Trans-Siberian in Moscow on a Friday morning in December; he is accompanying the jewel merchant going to Harbin, in the heart of Manchuria. The train itself is a microcosm of international technology—“hatboxes, stovepipes, and an assortment of Sheffield corkscrews.”

But it is also carrying “coffins from Malmo filled with canned goods and sardines in oil,” and as the poem unfolds, images of violence become more and more obtrusive. At first, the references are sexual—“I wanted to drink them [the women] down and break them”—but quickly the vision turns to “all those houses and all those lives / And all those carriage wheels raising swirls from the broken pavement,” which, says the poet, “I would have liked to have rammed into the roaring furnace / And I would have liked to have ground up their bones.”

Bombast, hyperbole, violence as Cendrars travels westward toward Manchuria, in the company of his amie, the little prostitute Jeanne, named for Joan of Arc, who keeps asking him when they can go back to Paris. The mood darkens. At first, war (the reference is to the Russo-Japanese War of 1905) is still far away. “In Siberia the artillery rumbled—it was war / Hunger cold plague, cholera.” But before long, “the telegraph lines” are seen dangling down from “the grimacing poles that reach out to strangle them” and “wild locomotives fly through rips in the sky.” Cendrars tries to entertain Jeanne (or himself) with fanciful exotic tales about lovers in the Fiji Islands or beautiful hanging gardens in Borneo, but he can’t avoid the sense that “we disappear into a tunnel of war.” And a note of fear comes in:

I saw

I saw the silent trains the black trains returning from the Far East and

Going by like phantoms . . .

I went to the hospitals in Krasnoyarsk

And at Khilok we met a long convoy of soldiers gone insane

I saw a quarantine gaping sores and wounds with blood gushing out

And the amputated limbs danced around or flew up in the raw air

These lines are astonishing in the premonition of what was to come. Written in 1913, before Cendrars knew that war would break out within a year and that in that war he would lose his right arm in battle, he anticipates the debacle. Indeed, in Au coeur du monde (1917), written not long after Cendrars lost his arm, read, “Ma main coupée brille au ciel dans la constellation d’Orion” (“My broken hand shines in the sky in the constellation Orion”). That image is anticipated in the Transsibérien by images of gaping sores, blood gushing, and trains disappearing. In the dream vision that follows, Jeanne has disappeared, and the poet, alone, is playing the piano.

Finally the dream dissolves. Cendrars steps off the train just as the offices of the Red Cross are set on fire. And now, without a break, we are suddenly back in an everyday Paris. In this “simultaneous” poem, narrative is replaced by descriptive noun phrases in apposition and hyperbole — “O Paris / Main station where desires arrive at the crossroads of restlessness” — and the poet wishes he had never left home. Now friends surround him like “guard rails,” women like “lighthouses.” In the end, there is nothing to do but to go to the Lapin Agile and have a drink. And the poem ends with an apostrophe to “Paris / City of the incomparable Tower the great Gibbet and the Wheel.” The gibbet is, of course, the guillotine, and in this context both the Eiffel Tower and the Ferris wheel for the Paris Exposition of 1900 seem sinister. The montage of sensations, images, and narrative fragments, the time-shifts from past to present and back again: all these make Cendrars’s poem a prescient elegiac homage to the Paris of the avant-guerre.

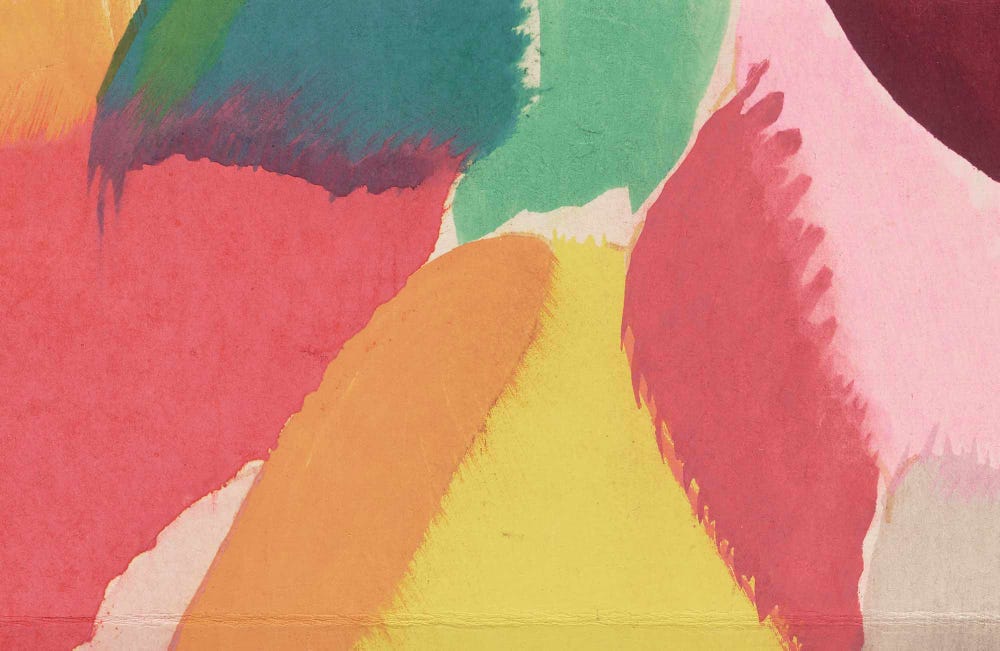

What does all this have to do with Sonia Delaunay’s imagery? Toward the bottom of the panel, we see black and brownish cloud shapes that look somewhat ominous: a storm, perhaps, is heading for the tower. But the little red phallic tower inside the orange-green wheel remains childlike and witty: one wonders why Delaunay’s lovely rendering of the poem is so serene, so pretty. In the end, this “artist’s book” is thus a study in contrasts. Just as the pochoir juxtaposes primary colors, so image and word present a contrast between the joie de vivre of the poem’s opening and its odd mix of buffoonery, high spirits, and a deep-seated anxiety.