February aka “African American–Black–Afro–Negro–Colored History Month”

By Nashormeh Lindo

February 12, 2021

Richard Mayhew, Spring Series #1, 1997. Watercolor, 10 1/2 x 14 1/2 in. (26.7 x 36.8 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, Museum purchase, Judith Clancy Fund, 1998.72. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

February is also known as Black History Month, an observance that originated in the United States. Recently it has gained official recognition in Canada. (Interestingly, it is also celebrated in Ireland, the Netherlands, and the UK—in October). For many years, I felt that the shortest, coldest month of the year (I grew up in Philly) was simply not sufficient to celebrate, explore, or magnify the rich history of the peoples of the African Diaspora. As an artist, educator, historian, and, most recently, Chair of the California Arts Council, I have made it my business to study and expose myself to the brilliance of artistic excellence across the board. Personally, however, I have always been particularly interested in African American art because it is my heritage and has often been left out of the art-historical canon. I worked at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in the 1990s, and in February we would be inundated with requests from schools and corporations for some kind of obligatory Black History Month presentation. That’s when I learned to adopt the idea that “every month is Black History Month,” and that we should be celebrating the contributions of all peoples, continuously, throughout the year. It goes without saying that 2020 was fraught with difficulty, especially for the Black and Brown communities, which were disproportionately hit with the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and systemic racism. For me, celebrating Black lives and achievements is all the more essential now. In fact, acknowledgment of Black History Month has expanded beyond schools to include other educational and cultural organizations, such as museums, and even the business/corporate world.

—African proverbA Race without knowledge of its history is like a tree without roots.

February was chosen as Black History Month for a reason. The historian and author Dr. Carter G. Woodson felt that African American contributions to the history of this nation and the world were “overlooked, ignored and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who used them. Race prejudice,” he concluded, “is merely the logical result of a flawed tradition, the inevitable outcome of thorough instruction to the effect that the Negro has never contributed anything to the progress of mankind.” In 1926 Woodson pioneered the celebration of Negro History Week, designated for the second week of February to coincide with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln.

Interestingly, that same year, the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library in Harlem purchased the bibliophile and collector Arturo Schomburg’s vast collection of books, manuscripts, prints, paintings, and other materials related to the African Diasporic experience, thus forming the foundation for the world-renowned Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Schomburg, a self-described Puerto Rican of African descent, had once allegedly been told by a fifth-grade teacher that his people had “no history, no heroes and no great moments.” This led him to pursue and amass a vast collection of the material proof of Black historic accomplishment. It was the height of a Black cultural awakening, the New Negro Movement, also known as the Harlem Renaissance, and the collection provided the “vindicated evidence” of Black achievement throughout history and the sustenance for new and powerful voices of creative expression. The library also hosted lectures, performances, and art exhibitions that provided a platform for Black artists and writers and that made the collection more accessible to the wider public. I believe we are currently experiencing a contemporary cultural renaissance—this time it is global.

—African proverbKnowledge is better than riches.

One prominent artist from the Harlem Renaissance who is represented in the de Young collection is Aaron Douglas. A pioneering Africanist and modernist, Douglas is the visual artist most often associated with the New Negro Renaissance in Harlem. His illustrations appeared on book covers and posters as well as in numerous journals and magazines, including the NAACP’s The Crisis and the National Urban League’s Opportunity, two major publications from the period. He was the only African American illustrator for the defining book of the time, The New Negro (1925), an anthology edited by Dr. Alain Locke. Douglas’s work helped set the visual tone of the era by incorporating ancestral motifs combined with aesthetic, social, and political themes. His work Aspiration (1936) is one of two extant paintings from a four-part mural commissioned for the Texas Centennial. The painting depicts themes such as the legacy of slavery as foundational to American history, commerce, and culture; the Great Migration of Black Americans from the agrarian South to the industrial North; and the idea that with exposure to educational opportunity, art, and science (think STEAM), African Americans would have the tools to enter into the future and to help form a more just and perfect society. Even though much progress has been made by African Americans in the many fields of endeavor depicted in Aspiration, Douglas’s utopian vision of the proverbial City on the Hill, with its attendant promise of an equitable, productive, enlightened, and prosperous nation, is still an elusive dream for many. In this current climate of racial strife, lost jobs, and homelessness, the struggle continues. Aspiration proffers a relevant and hopeful vision, and reminds us to keep our eyes on the prize.

Aaron Douglas, Aspiration, 1936. Oil on canvas, 60 x 60 in. (152.4 x 152.4 cm). Museum purchase, 1997.84. © Heirs of Aaron Douglas/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

—Harry EdwardsWe must teach our children to dream with their eyes open.

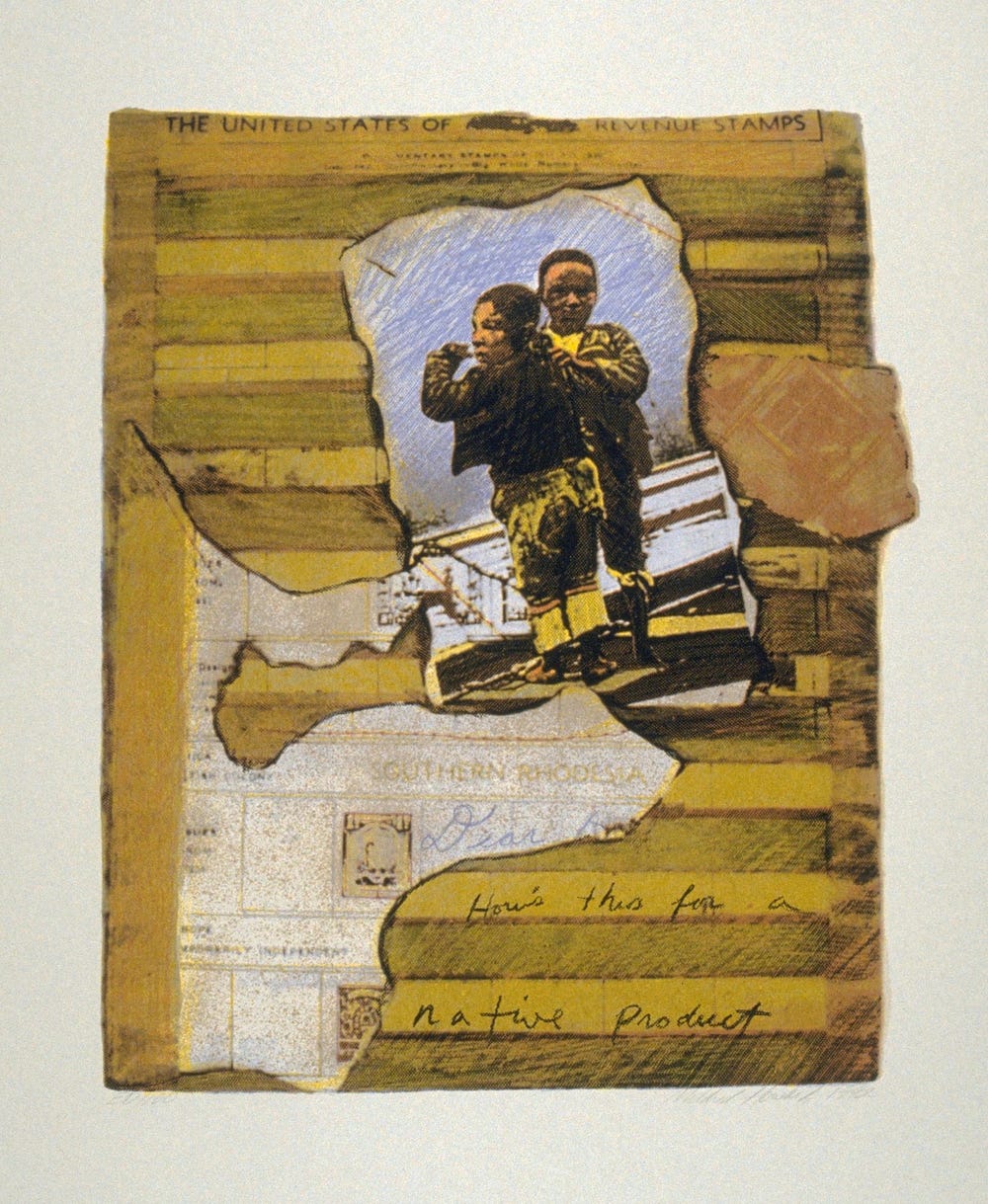

In 1970 Negro History Week was expanded to the entire month of February, and in 1976 it was designated “Black History Month” nationally. Interestingly, February is the birth month of numerous luminaries of African descent, including Langston Hughes, Richard Allen, Rosa Parks, Yara Shahidi, Hank Aaron, Bill Russell, Michael Jordan, Michael B. Jordan, Julius Erving, Smokey Robinson, Rick James, Dennis Edwards, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Leontyne Price, Nina Simone, Sidney Poitier, Joshua Redman, Augusta Savage, Deborah Willis, Fats Domino, Natalie Cole, Eubie Blake, Roberta Flack, Erykah Badu, Bob Marley, Alison Saar, Horace Pippin, William Artis, Raymond Holbert, Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Rihanna, Huey Newton, Samella Lewis, Ollie Harrington, Gregory Hines, Maceo Parker, Aida Overton Walker, JA Rule, Ice-T, and many others of note. In addition, Bay Area community activist Mable D. Howard and W. E. B. Du Bois, who once danced together, both had birthdays in February. With so many notable figures born in this month, Woodson was definitely on to something. (It’s ironic that these are all babies conceived around Juneteenth, in perhaps an unconscious commemoration of Emancipation!) Speaking of Mable Howard, her daughter Mildred’s work is also in the de Young collection. Of her silkscreened print entitled How’s This for a Native Product?, from the portfolio Beyond (1992), the artist says:

The two boys in the image came from a stereograph post card that I had collected. The piece is part of a series I did about my family’s move from Texas to California; what they left behind and what they brought with them. These stereotypical images of Blacks were often combined with those depicting ordinary Black families. Although none of my family members were used in this piece, it makes reference to how the media uses such images to plant negative thoughts about those that look different. The work portrays both the satire and the reality of racial injustice in this country.

Mildred Howard, How's this for a native product?, 1992. Color photo screenprint. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Frances Tullis and Reginald Leighton Vaughan Memorial Fund, gift of Reginald Bethune Vaughan and Dr. and Mrs.Donald Heyneman Fund, 1992.146.6. © Mildred Howard

Unfortunately, in the current sociopolitical climate of this country, we find that negative stereotypes continue to be propagated to marginalize Black people and to justify inequity, racial profiling, and violence against Black bodies and other communities of color. Art has consistently given voice to those who feel they have no say, and expressed the sentiments of the masses. Because art has the power to heal and to change the narrative, I remain cautiously optimistic.

—Alexandre DumasAll human wisdom is contained in these two words—Wait and Hope.

Elizabeth Catlett, Stepping Out, 2000. Laminated mahogany, 64 1/2 x 21 x 17 1/2 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, The Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. Art Fund, Inc., Beta Upsilon Boulé - Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity, The Links, Incorporated - San Francisco Chapter, Fine Arts Museums Tribute Funds, Ms. Del M. Anderson and Mr. John Handy, Mrs. Marguerite Archer, Rena Merritt Bancroft, PhD; Ms. Jo-Ann Beverly, Rev. "J" Edgar Boyd, Mrs. Mary Pat Cress, Mr. and Mrs. Richard Geist, Maxwell C. and Frankie Jacobs Gillette, Mr. and Mrs. Daniel Johnson, Jr.; Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Lathan, Mr. and Mrs. Terry E. Perucca and Dr. Alma Ribbs, 1999.199. © Catlett Mora Family Trust/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Elizabeth Catlett’s Stepping Out (2000) reminds me of the central role Black women have always played and continue to play in our culture and politics. This past year, women like Kamala Harris, London Breed, Barbara Lee, Holly Mitchell, Sydney Kamlager-Dove, Maxine Waters, Stacie Abrams, Keisha Bottoms, Val Demings, Karen Bass, Muriel Bowser, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi (the co-founders of Black Lives Matter) have demonstrated the power and bravery it takes to effect change in society. These women come from a long line of fearless activists who have often put their lives and careers on the line in order to confront the forces of oppression. Stepping Out is a visual affirmation of that strength and style, and asserts an unapologetic acceptance of a standard of beauty celebrating the Black woman’s body. The heroines in Catlett’s oeuvre show a firm resolve in overcoming the obstacles of racism and sexism that have plagued our existence for centuries.

A further affirmation of this resolve is the fact that there is currently a record number of Black women in leadership roles in our cultural and political systems. For example, the Black Lives Matter movement, founded by three women, has been nominated for the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize for the way its calls for systemic change have spread around the world, and has become an important global movement to fight racial injustice everywhere. People are literally “stepping out” in unity for that fair and just world Aaron Douglas envisioned. Most inspiring are the creatives who are using the arts to help spread the message of solidarity and social justice. February-born writer Audre Lorde once said, “It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.” This movement asserts that All lives will not matter until Black lives truly matter. It is a celebration and affirmation of our collective humanity.

—Paul RobesonArtists are the gatekeepers of truth.

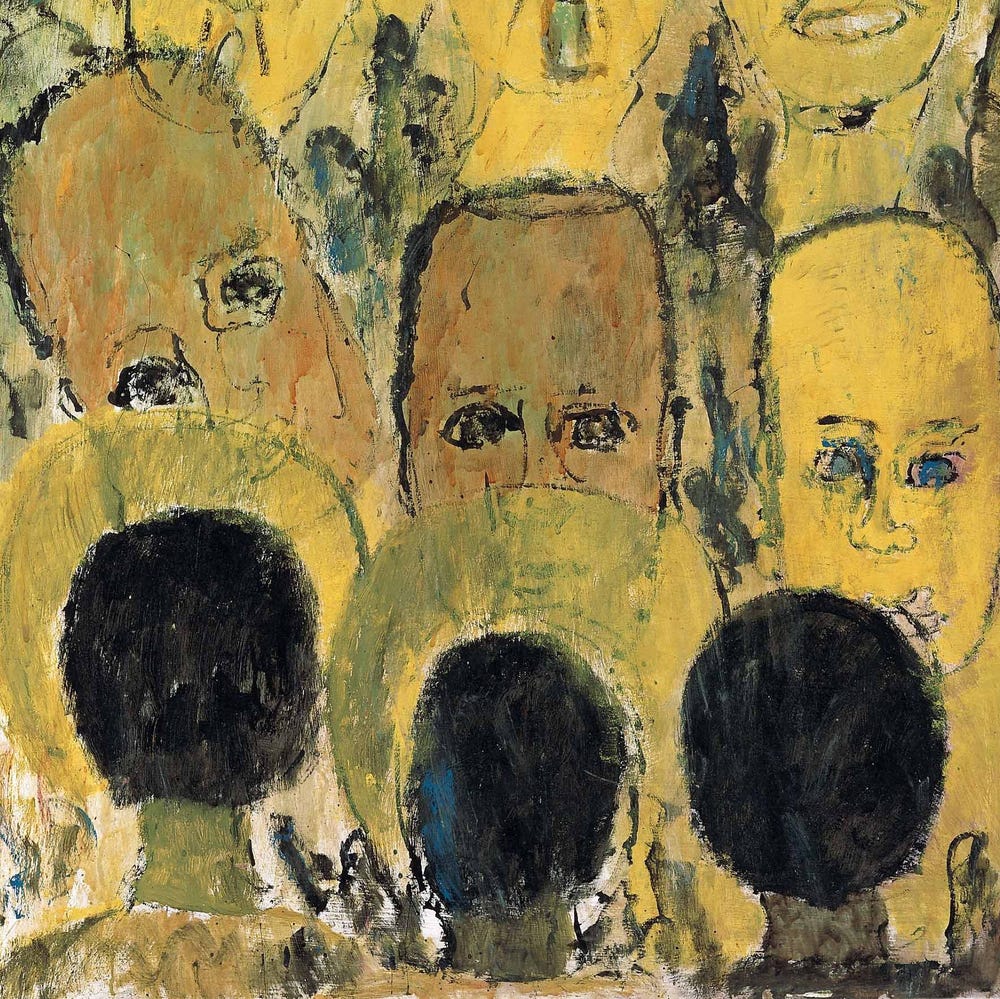

Robert Colescott, The Brown Grandmother of the Year, 1994. Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 72 in. (213.4 x 182.9 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of John B. and Jane K. Stuppin, 1997.47. © Estate of Robert Colescott / ARS (Artist Rights Society), New York, NY

Robert Colescott’s The Brown Grandmother of the Year (1994) is a luscious example of his skill as a painter’s painter and his ability to combine satire with biting social commentary. I first met Bob Colescott when his work was featured in the Black History Month exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art, where I worked in the 1980s. I didn’t know anything about him or his work, and was aghast when I first saw images of I Gets a Thrill Too When I Sees De Koo (1978), which features a depiction of a de Kooning–esque woman dressed as an Aunt Jemima–type character. I could not imagine presenting his work to a city with a majority Black population for Black History Month. But after a conversation with the artist and with scholar/curator Lowery Sims, who characterized Colescott’s paintings as “aggressively colorful gestural examples of funky Bay Area figuration and humor,” I got it and became a fan.

Interestingly, the first real artist Colescott met as a child also has work in the de Young’s collection. Sargent Claude Johnson worked with Colescott’s father on the railroad, and his daughter was a playmate of Robert’s. Standing Woman (1934) is a sculpture by Johnson, a prolific artist who worked with the Works Progress Administration in San Francisco and could be considered a West Coast representative in the second wave of the Negro Arts Renaissance. The sculpture has a quiet strength in its simplicity. Its demeanor is also the opposite of the wily Black Madonna / Mammy persona of Colescott’s Brown Grandmother. According to the artist’s widow, Jandava Colescott:

This painting is strongly driven by textile artistry and is reminiscent of quilts, tapestries and banners: the Italian Palio banner, in particular. Grandmothers are perennially coaxing cheers from tears: and this one wrangles her attributes—savory, sweet, soft, delectable and deadly alike—into the staff of life itself. She has birthed, raised, and nurtured legions. A simperingly presented, and demeaning statuette from a seven fingered paw, the (Mammy Grammy) seems lacking, at best and offensive, at worse, with its white gloved pose, courtesy of Al Jolson. Nonplussed and with a resigned side eye informed by eons, her attention shifts to the task at hand. And, as the Universe cries out for her ministrations yet again, her chromatic nimbus, a chartreuse halo, coalesces into pulsating, curative rays of violet and Aztec gold.

Sargent Claude Johnson, Standing Woman, 1934. Terracotta, 15 3/8 x 4 1/2 x 4 in. (39.1 x 11.4 x 10.2 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum collection, Federal Art Project, X1993.1

The Grandmother of the Year trophy/award adds insult to injury. Colescott’s painting is yet another nod to the myth of the central role Black women have played in the world as stereotypical caretakers with no power or recognition, little support, and all of the attendant assumptions, burdens, and indignities.

I would be remiss not to mention the work of Joshua Johnson in the de Young collection. Johnson, active in Baltimore from the late 18th to the early 19th century, was the first African American to be recognized as a professional artist and portrait painter. In a 1798 newspaper ad posted by the artist, he refers to himself as “a self-taught genius who has had to overcome many insufferable obstacles in pursuit of his craft.” This is indicative of the plight even of Free Black people during the antebellum period of this country’s history. Johnson’s Letitia Grace McCurdy (ca. 1800–1802) is a classic example of his skill painting children.The elements of the little red shoes, the puppy, and a hint of the landscape in the background are signature motifs. Given the circumstances, it was an act of defiance for a Black man to pursue a career in the fine arts in the nascent years of America.

Joshua Johnson, Letitia Grace McCurdy, ca. 1800–1802. Oil on canvas, 41 x 34 1/2 in. (104.1 x 87.6 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Acquired by public subscription on the occasion of the centennial of the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum with major contributions from The Fine Arts Museums Auxiliary, Bernard and Barbro Osher, the Thad Brown Memorial Fund, and the Fine Arts Museums Volunteer Council, 1995.22

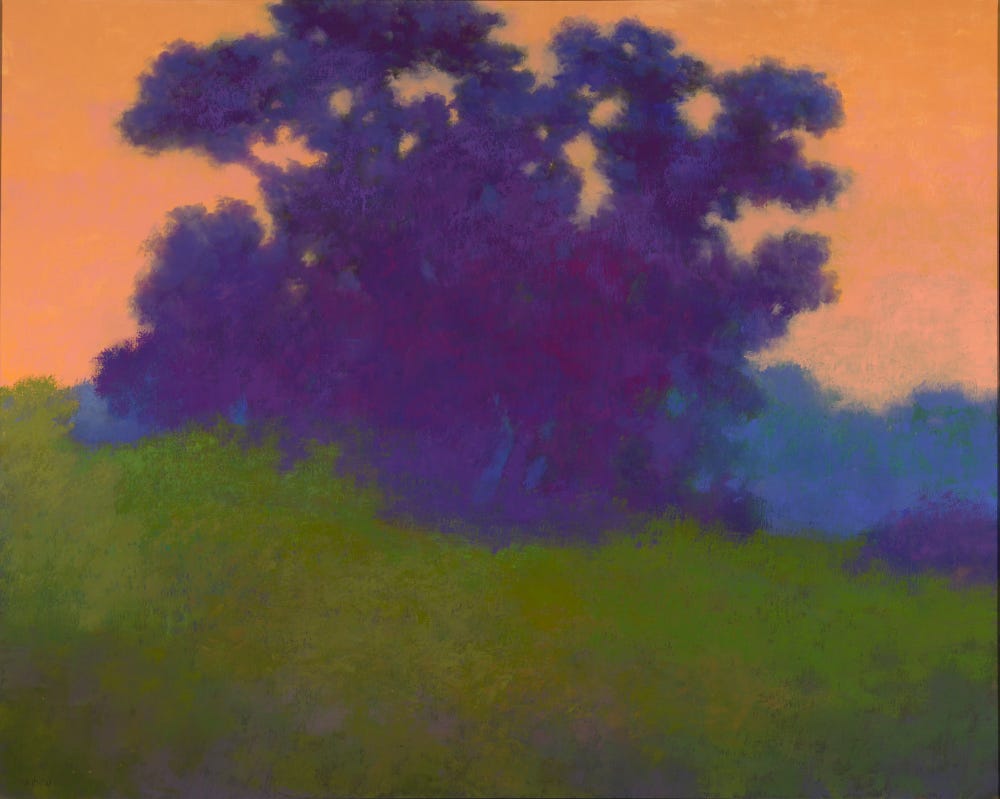

Finally, this past year has brought the environment into sharp focus and put climate change in the forefront of our collective consciousness. With the historic wildfires in the West and unprecedented hurricanes in the East, we in the US have had to face the sobering reality of global warming and an understanding that we can no longer take Mother Earth for granted. Richard Mayhew’s lyrical, colorful painting Rhapsody (2002) is a reminder of the spirit inherent in the land. While the artist calls his paintings “mindscapes,” his work is an exploration of light, color, and forms in nature, and are evocative of its transcendent beauty. Inspired by the landscape, music, Impressionism, and his African American and Native American heritages, Mayhew has also been an integral part of the larger history of mid-century African American artists and educators. He was an original member of Spiral, a collective of Black artists that grew out of the call for a visual arts component to the Civil Rights Movement. He also taught at several universities over the course of his career. There is a meditative quality about Mayhew’s work. The colors are rich yet soothing. But his work is also a clarion call for the preservation of the environment, for beauty and for harmony. In spite of the pandemic and shutdown, he is still painting, enthusiastically, at the age of 96. Mayhew is an inspiration to us all, and his example demonstrates that no matter what, keep working, keep creating, and surround yourself with beauty. Coda: Black is still, essentially, Beautiful.

Richard Mayhew, Rhapsody, 2002. Oil on canvas, 48 x 60 in. (121.9 x 152.4 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Volunteer Council Art Acquisition Fund, 2010.2. © Richard Mayhew

—Langston HughesPerhaps the mission of an artist is to interpret beauty to people—the beauty within ourselves.