Confronting the Colossus: Two Female Artists Face the Steel Mill

By Lauren Palmor

July 24, 2018

“To me these industrial forms were all the more beautiful because they were never designed to be beautiful. They had a simplicity of line that came from their direct application to a purpose. Industry, I felt, had evolved an unconscious beauty—often a beauty that was waiting to be discovered. And recorded! That was where I came in.”

—Margaret Bourke-White, 1963

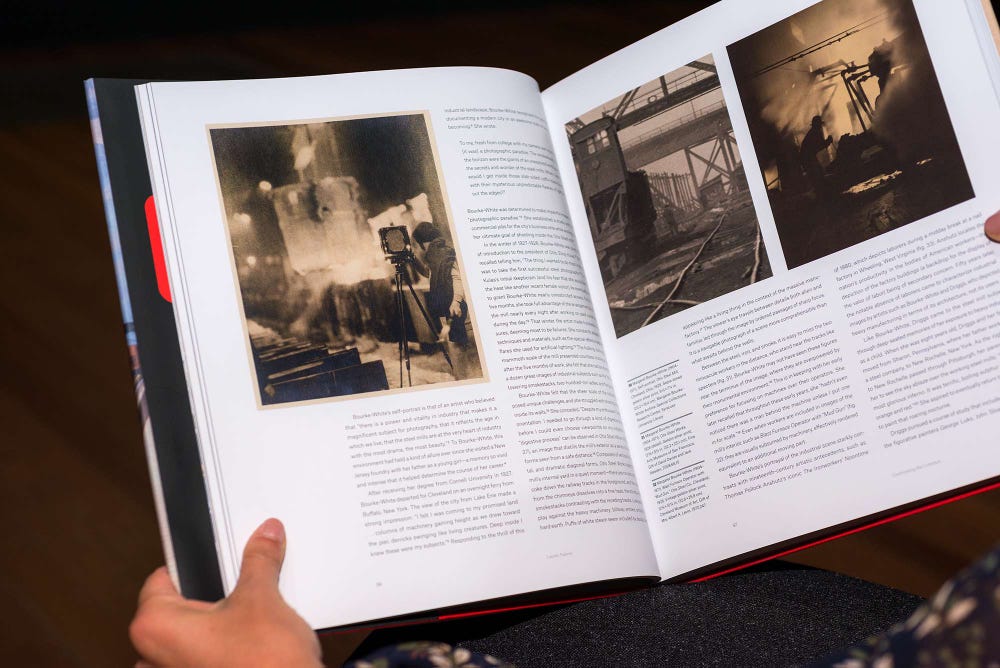

Margaret Bourke-White’s Self-Portrait, Otis Steel Mill (1928), which was on view in the exhibition Cult of the Machine, is an unconventional depiction of an artist at work: the photographer stands at the edge of her image, ceding the picture to an enormous ladle of molten iron. With her face turned away from the viewer and her body truncated by the frame, she appears to defer to the majesty of her subject.

Margaret Bourke-White’s Self-portrait, Otis Steel Mill, Cleveland, Ohio (1928) (left), as seen in the exhibition catalogue for Cult of the Machine. On the facing page: (left) A detail from Bourke-White’s Otis Steel Works (1928); (right) Blast Furnace Operator with “Mud Gun,” Otis Steel Co., Cleveland (1928), also by Bourke-White. Art © Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo: Randy Dodson

Flowing Metal, Flying Sparks

Environments like the Otis Steel mill, the site of Bourke-White’s self-portrait, had appealed to the photographer since childhood, when she visited a New Jersey foundry with her father. The experience was both profound and influential: “I remember climbing with him to a sooty balcony and looking down into the mysterious depths below. ‘Wait,’ Father said, and then in a rush the blackness was broken by a sudden magic of flowing metal and flying sparks. I can hardly describe my joy...Later when I became a photographer...this memory was so vivid and so alive that it shaped the whole course of my career.”

—Margaret Bourke-WhiteI felt I was coming to my promised land...columns of machinery gaining height as we drew toward the pier, derricks swinging like living creatures. Deep inside I knew these were my subjects.

Years later, as Bourke-White traveled to Cleveland following her graduation from Cornell University in 1927, she again had an overpowering response to an industrial scene. Aboard an overnight ferry from Buffalo, New York, she glimpsed her destination from Lake Erie and instinctively recognized the potential for documenting a modern city in a state of being and becoming.

The young photographer saw a “power and vitality in industry” and believed that the steel mills were “at the very heart of industry.”

“To me, fresh from college with my camera over my shoulder, [it was] a photographic paradise. The smokestacks ringing the horizon were the giants of an unexplored world, guarding the secrets and wonder of the steel mills. When, I wondered, would I get inside those slab-sided coffin-black buildings with their mysterious unpredictable flashes of light leaking out the edges?”

A Steel Will

Determined to make impactful images of this “photographic paradise,” Bourke-White established a studio in Cleveland, taking on commercial work for the city’s business elite while passionately lobbying to gain access to Otis Steel mill. In the winter of 1927–1928, she broke through when she received a letter of introduction to Elroy Kulas, the mill’s president. “The thing I wanted to do most in the world was to take the first successful steel photographs,” she later recalled telling him.

Kulas was initially skeptical of Bourke-White’s proposal, fearing that the photographer would faint from the heat like another recent female visitor, but he eventually granted her nearly unrestricted access. For the next five months, Bourke-White took full advantage of the arrangement, visiting the mill nearly every night after working on paid commissions during the day.

Lauren Palmor, assistant curator of American art, points out the two mill workers, small in scale, situated in the background of Margaret Bourke-White’s Otis Steel Works (1928). Art © Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo: Randy Dodson

Woman vs. Machine

Bourke-White made hundreds of exposures that winter, although she deemed most of them failures. She constantly adapted new techniques and materials, such as the special-effects magnesium flares she used for artificial lighting. But the hulking darkness and mammoth scale of the mill presented countless challenges, and she struggled with shooting images inside its walls.

After five months of work, she believed that she had produced only a dozen great images of industrial subjects such as the “hot pigs,” towering smokestacks, two-hundred-ton ladles, and flying sparks. She conceded, “Despite my enthusiasm I needed orientation. I needed to go through a kind of digestive process before I could even choose viewpoints on my subjects.”

This “digestive process” can be seen in Bourke-White’s Otis Steel Works (1928), a photograph that distills the mill’s exterior to a series of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal forms. The image portrays the mill’s internal yard in a quiet moment—no cars carry coke down the railway tracks, and the smoke from the chimneys dissolves into a fine haze. Lively textures play against the heavy machinery: billowy smoke, smooth rails, hard earth. Puffs of white steam seem included by design, appearing as almost a living thing amid the massive manufactory.

Between the steel, iron, and smoke, it is easy to overlook the two minuscule workers in the distance, standing near the tracks like specters. Their diminutive portrayal is consistent with Bourke-White’s early tendency to focus on machines rather than their operators. Even when she includes workers in her images of the mill’s interior, as in this work, they are visually subsumed by machinery, as though they are merely more of its moving parts.

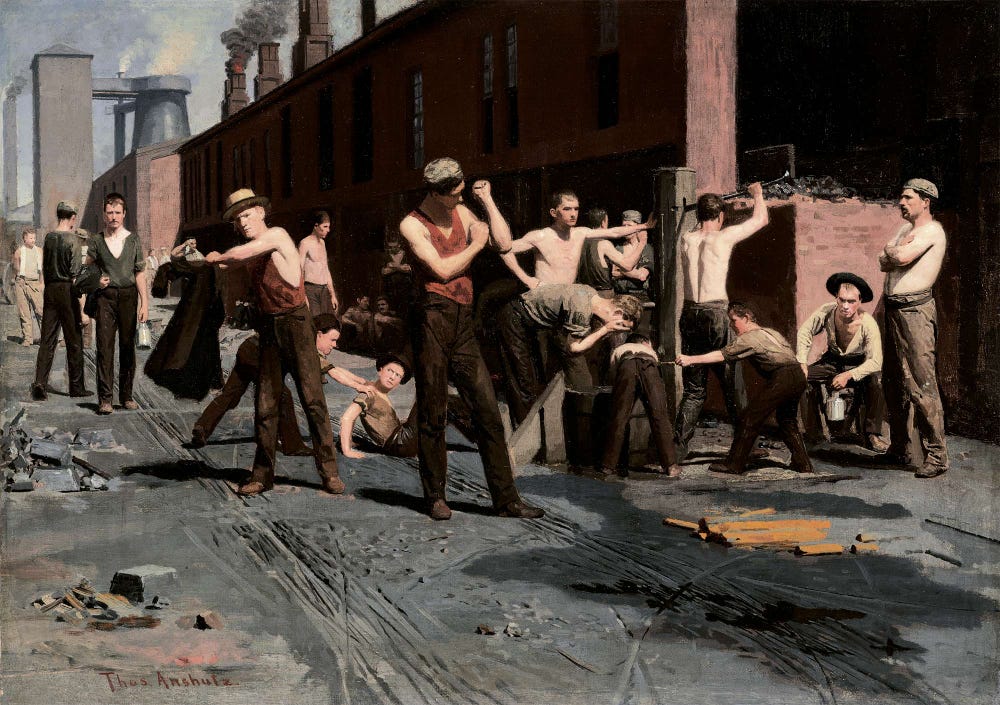

Thomas Pollock Anshutz, American (1851–1912). The Ironworkers' Noontime (detail), 1880. Oil on canvas. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd. 1979.7.4

Bourke-White’s portrayal starkly contrasts with nineteenth-century artistic antecedents. For example, Thomas Pollack Anshutz’s iconic Ironworkers Noontime of 1880 depicts laborers during their midday break at a nail factory in Wheeling, West Virginia. Anshutz locates the nation’s productivity in the bodies of American workers—the factory buildings are of secondary concern. Fifty years after Anshutz’s painting, the notable absence of laborers in images, such as those by Bourke-White, came to characterize the industrial depictions by Precisionist artists, who represented heavy manufacturing in terms of its architecture, not its operators.

—Elsie Driggs, on seeing the sky above a Pittsburgh steel millIt was the most glorious inferno. It was terrific, boiling sulphur yellow and orange and red.

Elsie Driggs in Pittsburgh

While Bourke-White was photographing the steel-making process in Cleveland, painter Elsie Driggs was portraying the industrial environment of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Like Bourke-White, Driggs had potent memories from her childhood of her exposure to heavy industry. When she was eight years old, she and her family moved from Sharon, Pennsylvania, where her father worked for a steel company, to New Rochelle, New York. As the night train to New Rochelle passed through Pittsburgh, her parents woke her to see the sky ablaze over the working steel mills, and she vowed to eventually return to Pittsburgh to paint that roaring nocturne.

As an adult, Driggs trained at the Art Students League in New York with the figurative painters George Luks, Maurice Sterne, and John Sloan. After studying for a year with Sterne in Italy from 1922 to 1923, she returned to New York, where she exhibited her own figurative watercolors and oils at the Daniel Gallery. In 1926, after saving enough money, she announced that she would travel to Pittsburgh to paint the steel mills from her childhood.

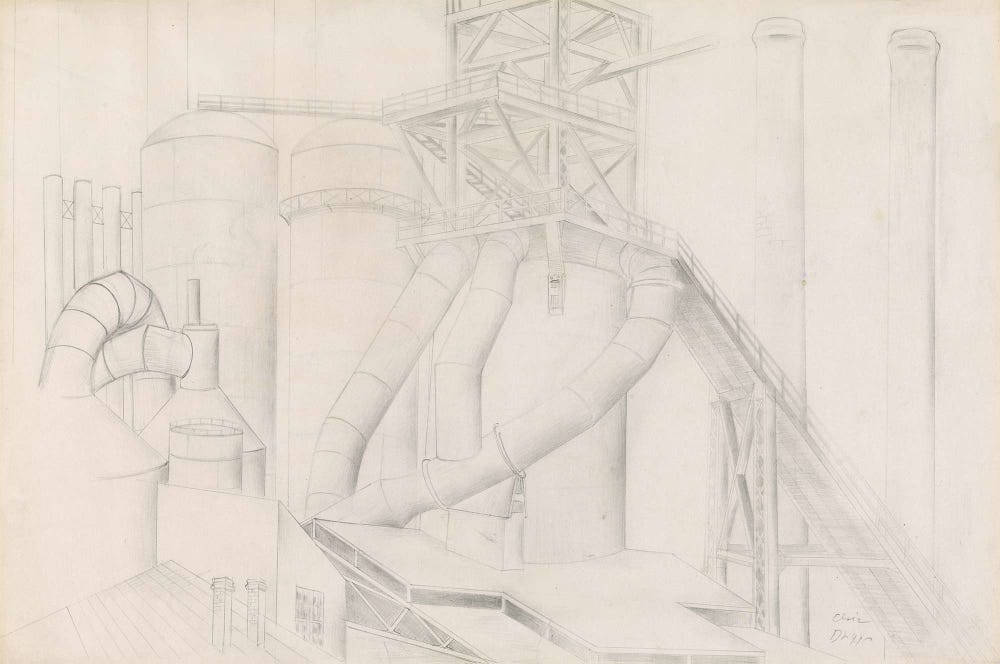

Elsie Driggs, Study for Pittsburgh, 1927. Graphite on paper, 12 × 14 3/4 in. (30.5 × 37.5 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 50th Anniversary Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Julian Foss, 80.6.3. Digital Image © Whitney Museum, N.Y.

Her Own Vantage Point

However, upon arriving in Pittsburgh, Driggs was disappointed to discover that there were no sulphurous flames to be seen—the steel mills had long-abandoned the fiery Bessemer process, and “the sky was totally black.” The artist turned her attention to the monumental architecture of the mill itself, locating poetry in the interplay between the industrial colossus and the darkened skies above. She described how “the particles of dust in the air seemed to catch and refract the light to make a backdrop of luminous pale grey behind the shapes of simple smoke.”

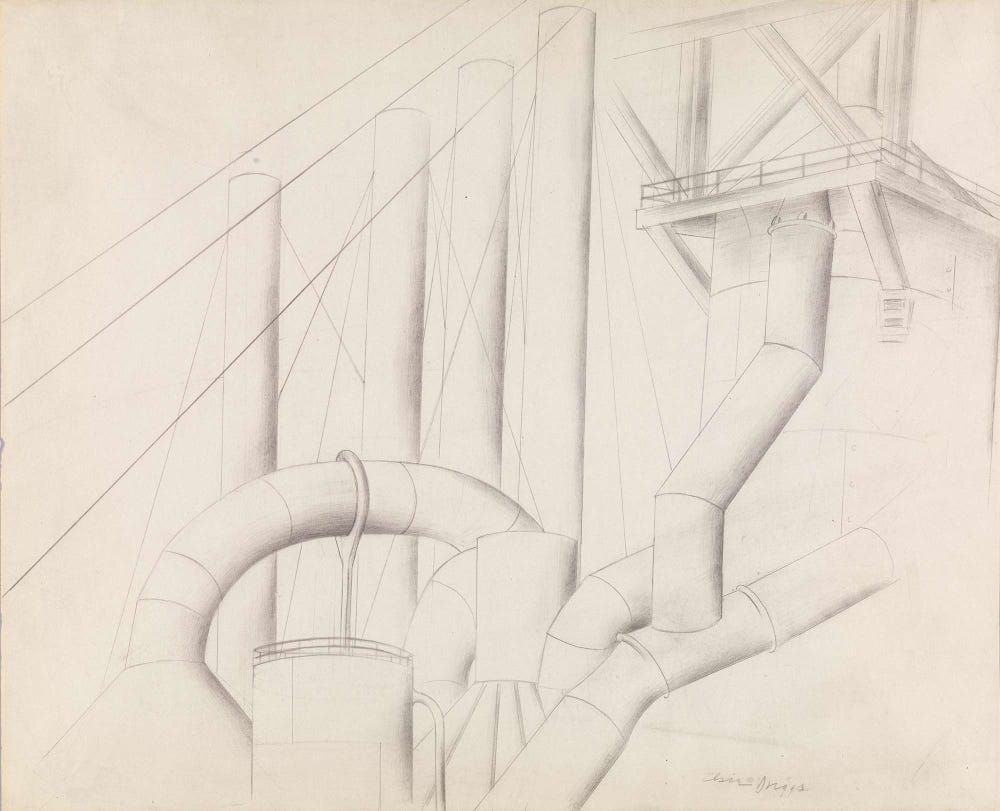

Elsie Driggs, Study for Blast Furnace, 1927. Graphite on paper, 12 1/8 × 18 1/8 in. (30.6 × 45.9 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 50th Anniversary Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Julian Foss, 80.6.2. Digital Image © Whitney Museum, N.Y.

Driggs quickly set out to secure access to Pittsburgh’s Jones & Laughlin Steel. Although she was armed with letters of introduction from her art dealer and a prominent collector, the steel mill viewed her with suspicion as both an artist and a woman; management saw her as a potential labor agitator or a spy from a rival firm. Driggs responded by changing course: “By the time they decided I was quite harmless, I didn’t care if I went in there anymore.” Instead she climbed uphill toward her boarding house, looking down on the mill’s smokestacks and girders and recognizing that the view she beheld “shouldn’t be beautiful. But it is.”

Elsie Driggs, Study for Pittsburgh, 1927. Graphite on paper, 12 × 14 3/4 in. (30.5 × 37.5 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 50th Anniversary Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Julian Foss, 80.6.3. Digital Image © Whitney Museum, N.Y.

From here, Driggs recorded her first impressions of the mill in pencil—“it was all I had so I drew it.” The resulting preparatory drawings for Pittsburgh (1927) and Study for Blast Furnace (1927) possess a precise elegance that amplified the might of the machine. However, the paintings that Driggs made from these sketches are more dramatic and less exact.

A Surreal Industry

Her painting Pittsburgh (1927) does little to describe the booming Pennsylvania city, instead offering a machine portrait of a place divided by thick smoke stacks and forebodingly dark architecture, silhouetted against a luminous sky. The severity of the shadows is relieved by a sobering mist, like the mitigating effects of the white steam in Bourke-White’s exterior image of the Otis mill.

Elsie Driggs, Blast Furnaces, 1927. Oil on canvas, 33 x 39 in. (83.8 x 99.1 cm). Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, 2017.1. From the Estate of Elsie Driggs

In Blast Furnaces (1927) (above), the second painting in the Pittsburgh series, the finesse of Driggs’s original drawing is replaced by a dense composition of metallic blacks and sturdy reds. She described the architecture of the final painting as “a potpourri of all the forms [of blast furnaces] that I saw on my way into Pittsburgh.”

—Elsie DriggsThe girders go nowhere; the smoke isn’t real...I guess I was always more or less a surrealist.

With its staggering sense of scale, tangle of calligraphic pipes, and subtle illustrative details, the painting presents the dreamlike fictions available to a painter who could sketch on site and later translate her observations in the studio. Driggs described how her finished paintings departed from their source material: “The girders go nowhere; the smoke isn’t real...I guess I was always more or less a surrealist.” Rather than a faithful transcription of the artist’s sketches, Pittsburgh and Blast Furnaces instead synthesize reality and imagination to capture the subject’s emotional essence.

A Secret Knowledge

Although both Bourke-White and Driggs were responding to what the latter termed an “inevitable rightness” in the steel mill, they adopted different approaches that contributed to their creation of two very distinct bodies of work. While Driggs drew the mills from a safe distance up on the hill, Bourke-White exposed herself to some of the same physical dangers that threatened Otis employees. Driggs improvised an elegant solution when she was denied access to the Pittsburgh mill. Bourke-White, on the other hand, refused to be rejected by Elroy Kulas, setting the course toward the nickname she would later earn from her colleagues at Life magazine: “Maggie the Indestructible.”

Over the course of their self-designed artist residencies, the two women sought to reveal the allure of steel mills through highly personal images. They both tangled with the unconventional beauty of the subject, which they perceived as a form of secret knowledge. While Driggs acknowledged that “this shouldn’t be beautiful,” Bourke-White felt “these industrial forms were all the more beautiful because they were never designed to be beautiful.”

Working in their respective media, both artists favored the exuberant or sublime effects of industrial architecture over the human aspects of industrial production. This preference may have been motivated, in part, by the ecstasy of the era: in 1927, Charles Lindbergh flew over the Atlantic, the Westinghouse Company debuted the Televox robot, and the Machine Age Exposition thrilled audiences with the design of the modern world. It was a time when the products of heavy industry provided the means for exhilarating experiences. Steel made the Machine Age possible, and these artists sought to make apparent the splendor of steel itself.

This essay was adapted from “Confronting the Colossus: Two Artists Face the Steel Mill,” by Lauren Palmor, assistant curator of American art, published in Cult of the Machine (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in association with Yale University Press; 2018).

Selected Bibliography

- Margaret Bourke-White. Portrait of Myself (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963).

- Geraldine W. Kiefer, “From Entrepreneurial to Corporate and Community Identities: Cleveland Photography,” in Transformations in Cleveland Art, 1796–1946, ed. William H. Robinson and David Steinberg (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1996).

- Howard Bossen, Eric Freedman, and Julie Mianecki, “Hot Metal, Cold Reality: Photographers’ Access to Steel Mills,” Visual Communication Quarterly 20, no. 1 (2013).

- Sharon Corwin, “Constructed Documentary: Margaret Bourke-White from the Steel Mill to the South,” in American Modern: Documentary Photography by Abbott, Evans, and Bourke-White (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010).

- Tom E. Hinson, “Recent Acquisitions,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 62, no. 2 (February 1975).

- Howard Bossen, Eric Freedman, and Julie Mianecki, “Shaped by Fire: How Photographers Gain Access to Steel Mills,” Meno istorija ir kritika / Art History and Criticism 9 [Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania] (2013).

- Ronald Elroy Ostman and Harry Littell, Margaret Bourke-White: The Early Work, 1922–1930 (Boston: David R. Godine, 2007)

- Françoise S. Puniello, “Elsie Driggs,” in Past and Promise: Lives of New Jersey Women, ed. Joan N. Burstyn (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1997).

- Constance Kimmerle, Elsie Driggs: The Quick and the Classical (Doylestown, Penn.: James A. Michener Art Museum, 2008).

- Susan T. Lubowsky, Precisionist Perspectives: Prints and Drawings (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1988).

- John Loughery, “Blending the Classical and the Modern: The Art of Elsie Driggs,” Woman’s Art Journal 7, no. 2 (Autumn 1986–Winter 1987).

- Whitney Museum of American Art, Drawing Acquisitions, 1978–1981 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1981).

- Ed Cray, Ramblin’ Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006).Thomas Folk, Elsie Driggs: A Woman of Genius (Trenton, N.J.: New Jersey State Museum, 1990).

- Ora Lerman, “Elsie Driggs,” in A Lifetime of Art: Six Women of Distinction, ed. Thalia Gouma-Peterson (San Francisco: Women’s Caucus for Art, 1982).

- Karen Tsujimoto, Images of America: Precisionist painting and Modern Photographer, exh. cat. (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1982).