Broadening Perspectives in the Care of Art

By Tamia Anaya, Jena Hirschbein, and Jane Williams

December 16, 2021

Working collaboratively across many departments at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the conservation team is responsible for the physical preservation of artworks in the Museums’ collections and those shown at the de Young and Legion of Honor in temporary exhibitions. As conservators, we work to understand how an artwork is constructed, the chemistry of the materials used to make it, and how they might change or deteriorate in different environments over time.

While we focus on the physical aspects of the artwork, we try not to lose sight of preserving its intangible aspects, too. For this, we learn about an artwork’s historical context, as well as its conceptual, functional, and cultural significance.

Understanding the less tangible aspects of an artwork, especially when it is created within a culture different than our own, requires incorporating varied viewpoints and experiences that museums have too often ignored. This understanding does not come from research or specialized expertise alone. It requires seeking out and listening to other voices. Our Museums’ commitment to anti-racism means making the time for this work.

Erin Algeo, Conservation Technician in Costume Mounting, Alex Grassi, Museum Technician, and Laura Garcia-Vedrenne, Mellon Fellow in Textile Conservation, dressing a mannequin in preparation for the spring 2022 Guo Pei: Couture Fantasy exhibition

We are rethinking our traditional models of collaboration, learning, and teaching to allow for a broader range of voices in the care of an artwork. Although we are grappling with ways we may still fall short, the following are examples of our efforts to include a greater diversity of people and perspectives in the stewardship of the artworks in our care.

Conversations with living artists

In the last two years we have looked for ways to better capture the perspectives of living artists from the moment their artworks enter the Museums’ collections. As conservators, we have a legal and ethical obligation to consult with living artists on any treatment or alteration of their work. Especially as the Museums build more comprehensive and materially eclectic collections, we can’t afford to miss out on learning directly from artist-makers well before their viewpoint may be needed to inform a decision about treatment or display.

In 2019, an opportunity to talk with local artist Alan Rath before his untimely death served as a poignant reminder of the urgency of recording and archiving information to ensure the integrity of the artwork and, in this case, its operability. In Rath’s 2001 electronic and mixed-media sculpture When Is Now, eyes shift on small LCD screens contained within a large wooden cage. Less than 20 years after he made it, however, the Museums had no record of what exactly would happen when the artwork was switched on. In the final months of his life, Rath shared important details about the artwork, including the digital algorithms that drive the movement of the eyes. Today, our team is working with colleagues in the Museums’ Registration and Collections Management departments, along with many from other areas throughout the Museums, to better archive information from living artists at the time the Museums acquire their work.

Alan Rath, When Is Now, 2001. Beech, Aluminum, Electronics, And LCDs, 27 x 46 x 18 in. (68.6 x 116.8 x 45.7 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, American Art Trust Fund, Paul Sack, and Cheryl Haines Funds, 2002.73. Image from Hosfelt Gallery

When the Museums acquired works by artists in The de Young Open, our paper conservators led a renewed effort to develop and circulate artist questionnaires. Often followed by interviews or email exchanges, the questionnaires record detailed information about how artworks were made and the artists’ intentions for the display and long-term care of the work.

Departments across the Museums are working together to integrate this outreach into our workflows, which in turn informs our new collections database and website. Diligently archiving knowledge provided through dialogues with living artists and community collaborators, while also expanding access to this information, ensures artworks are shown as artists intended them to be seen, even years into the future.

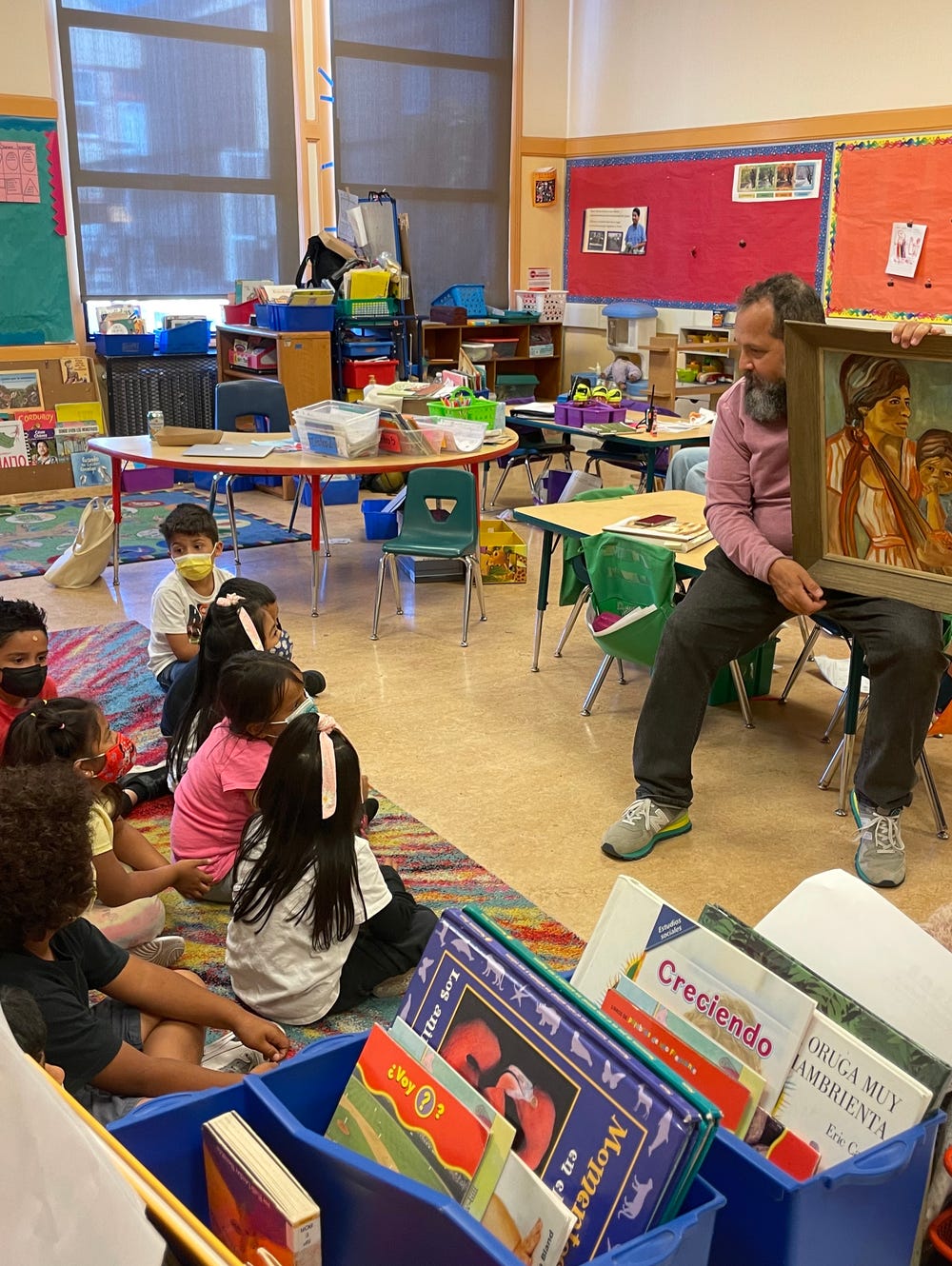

Temporary exhibitions also provide opportunities for conservators to support the vision of living artists. The Museums’ colleagues across many departments worked with co-presenters on the display of the upcoming Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo exhibition at the de Young. Robert Geary, Elem Pomo cultural leader, regalia maker, and co-presenter of the exhibition, supplied feedback about his headpieces featured in the exhibition. With Geary’s input and in dialogue with the curatorial and exhibitions teams, conservator Colleen O’Shea advocated for mounting the headpieces in a way that better demonstrates how they are worn than a more static display could do.

Colleen O’Shea, associate objects conservator, and Robert Geary, Elem Pomo cultural leader, discuss a headpiece featured in the Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo exhibition

Multi-directional learning

While conservators working today are expected to complete graduate study that combines aspects of studio art, chemistry, and art history or other humanities, our field remains rooted in a tradition of apprenticeship. Since the 1970s, more than 100 interns have passed through the Museums’ conservation departments. Hands-on internships and fellowships remain key ways for conservators to pass on experience and practical skills to the next generation. But as we strive for a greater diversity of voices, we are mindful that this requires challenging traditional hierarchies of learning. We embrace the ways interns and emerging conservators contribute essential knowledge to the Museums and how their fresh outlooks influence the practice of more experienced colleagues. Across the organization, we are recognizing interns’ vital contributions by ensuring that they are compensated for their work.

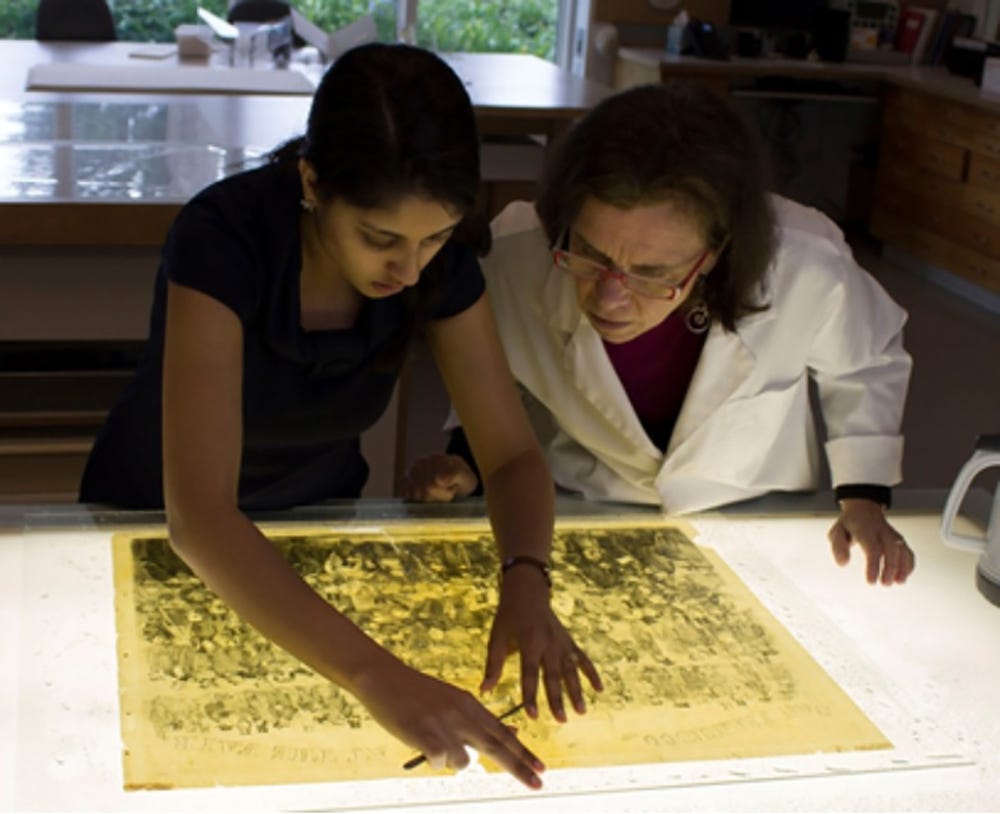

Anisha Gupta, former Mellon Fellow and Debra Evans, former Head of Paper Conservation, examine an artwork in the Paper Conservation Lab

The Museums’ current conservation fellows are here for continued postgraduate training. They are leaders in their departments, the Museums, and in communities beyond with their passion for and experience with the role language plays in the preservation of cultural heritage.

Tamia Anaya, Mellon Fellow in Paper Conservation, brings with her a professional, philosophical approach that sets out to build coequal collaborations with knowledge-bearers across disciplines and beyond the Museums in order to foster inclusion. Inspired in part by her previous work as project assistant for Untold Stories — a pioneering organization that engages directly with storytellers and community collaborators — Anaya promotes the perspective that a collection item’s materiality is inextricably linked to the oral histories and sociopolitical context that inform it.

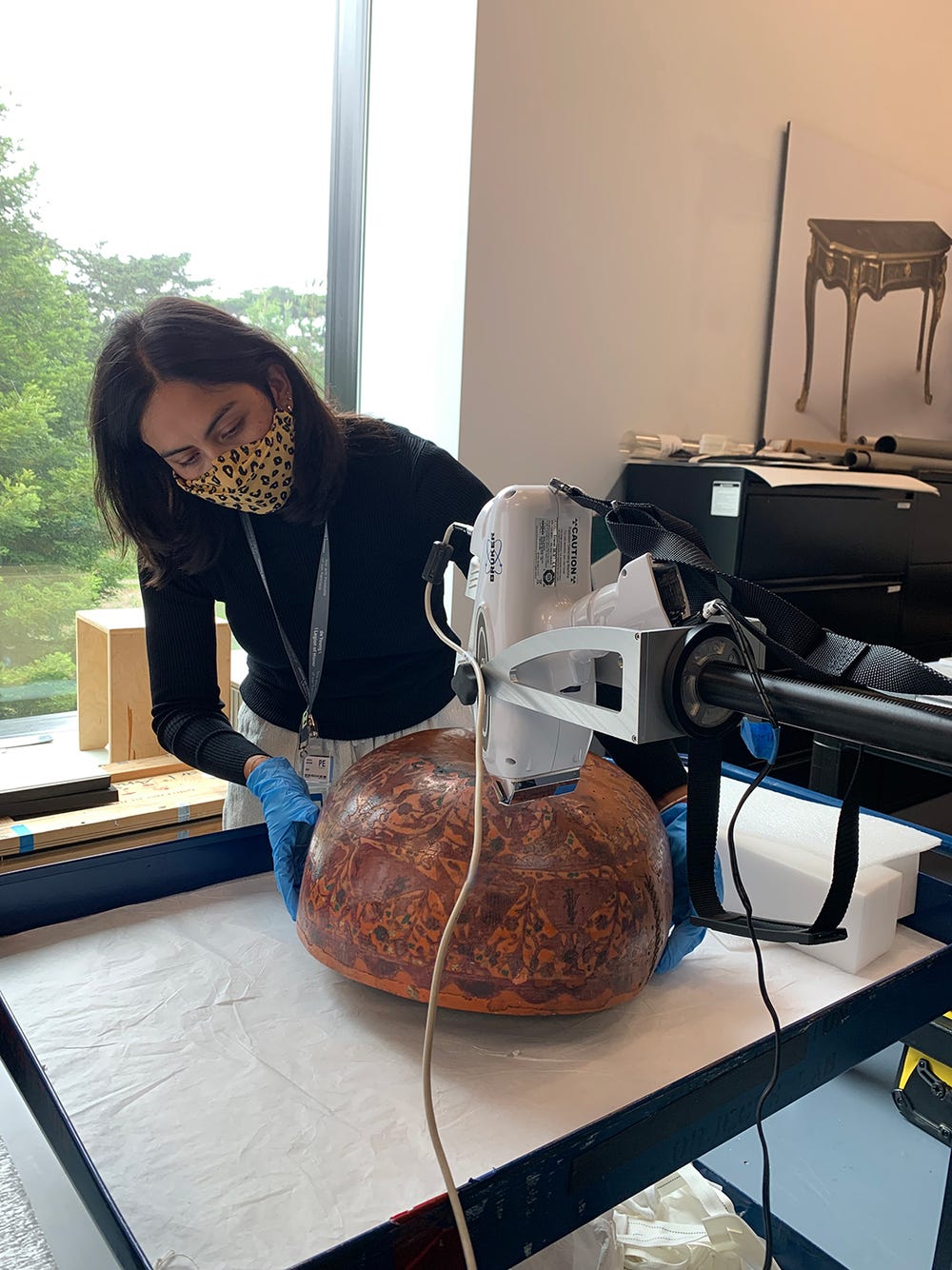

During graduate research, Anaya learned directly from lacquer makers in Olinalá, Mexico, and later worked with scientists to chemically identify the materials used. This work led to Anaya's translation into English of Nahuatl and Spanish terms used for materials and techniques, and to a common understanding of this practice. Sharing this information with the Museums, Anaya shed light on the story behind the lacquer objects in our collections, but, most importantly, this study served to push against the conventional idea of who is an expert and authority about a work of art.

Conservation Mellon Fellow Tamia Anaya conducting analysis on the Museums’ lacquer gourd

Laura Garcia-Vedrenne, Mellon Fellow in Textile Conservation, brings to her work at the Museums a commitment to expand access to training and educational resources across multiple languages. As a non-native English speaker, she provides insight on how to improve such access within the Museums’ community.

Beyond the Museums, Garcia-Vedrenne helped in the Spanish translation of a rich web-based resource, Museum Pests.Net, which addresses the damage by pests to cultural heritage objects as a global result of climate change. This fall Garcia-Vedrenne partnered with Winterthur Museum textile conservator and WUDPAC conservation professor Laura Mina to present a course on the use of gels for stain reduction on textiles. The course was offered to Spanish-speaking conservators in Chile, Argentina, and Brazil through a collaboration with Comité Nacional de Conservación de Textiles (CNCT).

Laura Garcia-Vedrenne treating a textile fragment from the Museums’ Julia Brenner collection

Garcia-Vedrenne, Anaya, and countless other fellows and interns contribute to symbiotic professional relationships within the Museums’ Conservation department. The Museums’ collection and the field at large benefit from their perspectives, as they benefit from the wealth of knowledge and skills within their respective departments.

Conclusion

As conservators, we are privileged in many ways. Our daily work brings us close to an incredible array of art, artifacts, and artists. We acknowledge that our work does not occur in a vacuum and appreciate collaboration. Yet, collaborative approaches to conservation work are not routinely part of museum practice. Time pressures and competing priorities often sacrifice a diversity of perspectives that might change how we display or preserve art. What's more, we recognize the distinction between “collaboration” born of necessity in a museum and building genuine relationships with individuals beyond the institution.

Conservators are taught early on to continuously question our assumptions in order to understand how something is created. This applies to our philosophical and ethical approaches as well, providing continued self-reflection and a chance to modify what we think we know as museum practitioners. At best, it allows for new insight on who is positioned to “care” for collection items and how to make room for voices that are not being represented.

Text by Tamia Anaya, Mellon Fellow in paper conservation; Jena Hirschbein, assistant objects conservator; and Jane Williams, director of Conservation.

Learn more about Conservation at the Museums.