5 Botticelli Artworks We Only Just Found Out About

By Antonia Smith, digital project manager

December 7, 2023

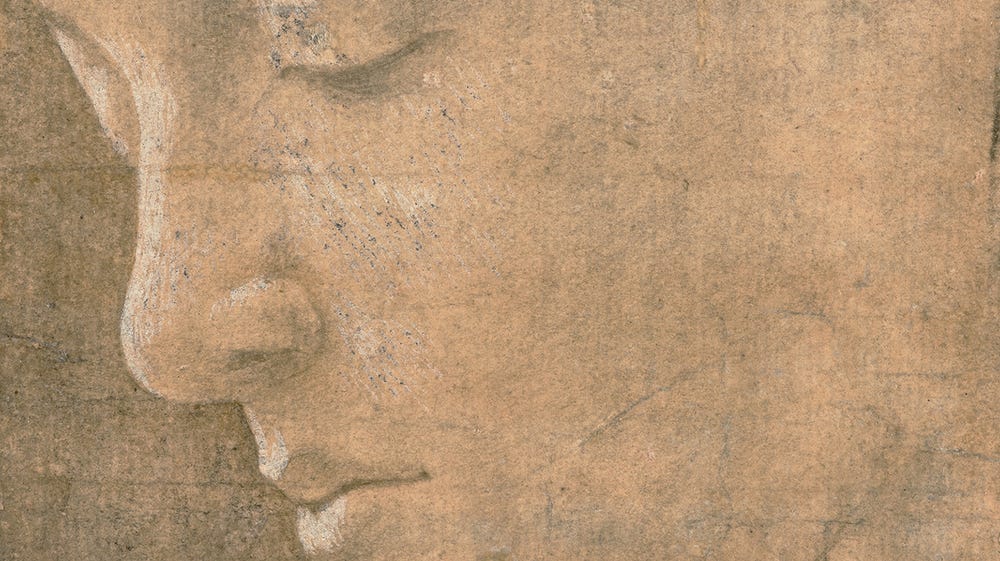

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, Florence, ca. 1445–1510), Head of a Woman in Near Profile Looking down to the Left (detail), ca. 1468–1470. Metalpoint, light gray wash, heightened with white, on yellow-ocher prepared paper, 5 1/4 x 4 3/16 in. (13.4 x 10.7 cm). Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford, 0060 (JBS 44)

While Sandro Botticelli (ca. 1445–1510) is known for some of the world’s greatest paintings, a lesser known (but equally impressive) part of his work is his drawings. Less than 40 known drawings by Botticelli exist today. In preparation for the exhibition Botticelli Drawings, curator Furio Rinaldi conducted thorough technical and stylistic analysis of previously unattributed drawings, making connections to early paintings by the artist. Through this research, he attributed five new drawings to Botticelli.

1 + 2. Head of a Woman + Head of a Man

Sandro Botticelli, Head of a Woman in Near Profile Looking down to the Left, ca. 1468–1470. Metalpoint, light gray wash, heightened with white, on yellow-ocher prepared paper, 5 1/4 x 4 3/16 in. (13.4 x 10.7 cm). Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford, 0060 (JBS 44)

Sandro Botticelli, The Virgin and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist (“Madonna of the Rose Garden”) (detail), ca. 1465–1470. Tempera and gold on poplar panel, 35 11/16 x 26 3/8 in. (90.7 x 67 cm). Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures

Delicately drawn in metalpoint, following a technique typical of the artist, these two head studies were likely cut from the same yellow-ocher sheet of paper. Head of a Woman in Near Profile Looking down to the Left (ca. 1468–1470), can be linked to The Virgin and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist (ca. 1465–1470). The round eyes, overarched eyebrows, and small, protruding lips of the figure closely match those of the Virgin in the painting.

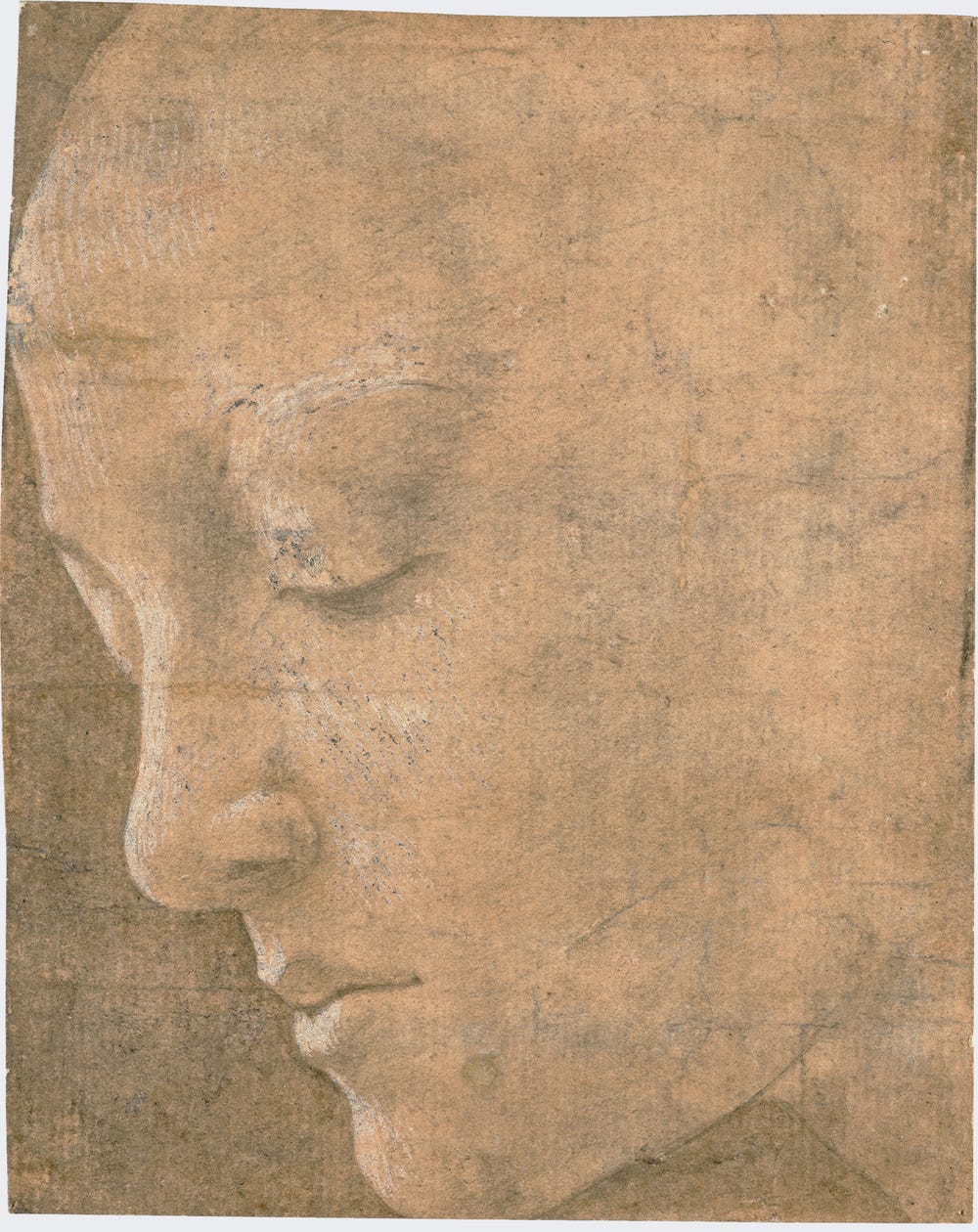

Sandro Botticelli, Head of a Man in Near Profile Looking Left, ca. 1468–1470. Metalpoint, traces of black chalk, gray wash, heightened with white, on yellow-ocher prepared paper, 5 3/16 x 4 5/16 in. (13.2 x 11 cm). Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford, 0061 (JBS 45)

Sandro Botticelli, Adoration of the Magi (detail), ca. 1478/1482. Tempera and oil on poplar, 27 9/16 × 41 in. (70 × 104.2 cm) National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.22

Head of a Man in Near Profile Looking Left (ca. 1468–1470), can be linked to the third onlooker at right in Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi (1478/1482). The lighting and facial structure — the prominent nose, protruding chin, and near-open lips — align closely with the witness in the Adoration.

Although prepared for specific paintings, the faces in Head of a Woman and Head of a Man became templates reused by Botticelli and his workshop. The woman became a pattern for works such as the Madonna della Loggia and the Virgin Adoring the Sleeping Christ Child. The man can be seen repurposed for the angel at right in the Madonna and Child.

3. Profile Studies

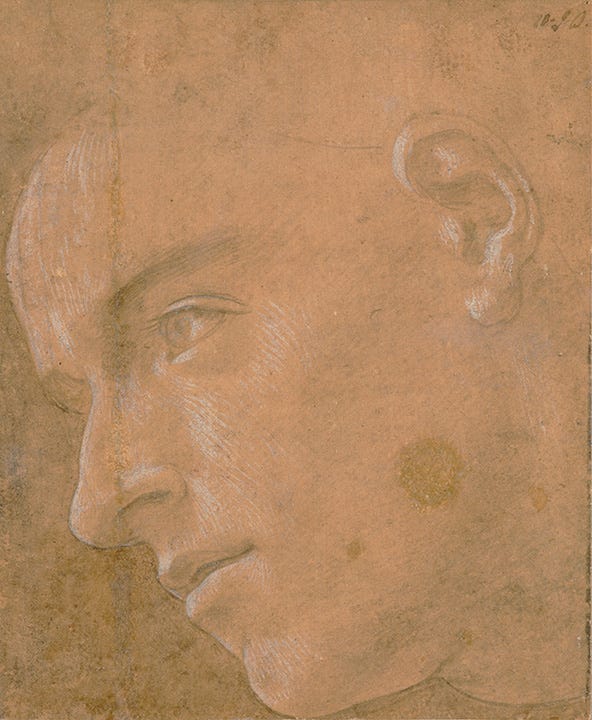

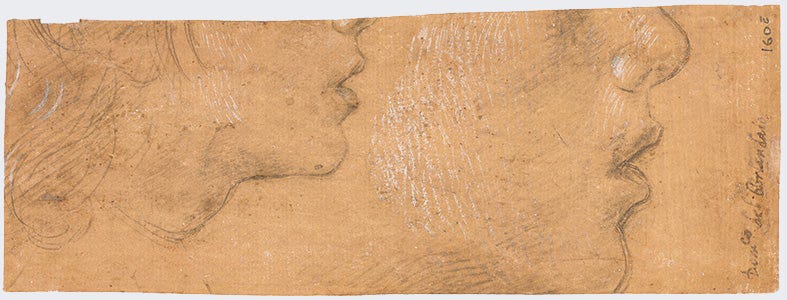

Attributed to Sandro Botticelli, Two Partial Studies of a Profile (verso), ca. 1475. Metalpoint, heightened with white, on yellow-ocher prepared paper, 2 13/16 x 7 7/16 in. (7.1 x 18.9 cm). Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, Florence, 160 E

Sandro Botticelli, The Annunciation (Cestello Annunciation) (detail), 1489. Oil on panel, 59 1/16 x 61 7/16 in. (150 x 156 cm), Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence, 1890 no. 1608

Two cropped drawings match the profile of the archangel Gabriel in the celebrated Cestello Annunciation (1489). They are metalpoint on yellow-ocher paper, used commonly by Botticelli. A light hatching produces shadows, especially evident under the neck. The light strikes the figure from upper left, and the shadows align with those of the painting. They are rendered by short, curved lines of white, spread with a fine-tip brush, a technique typical of Botticelli.

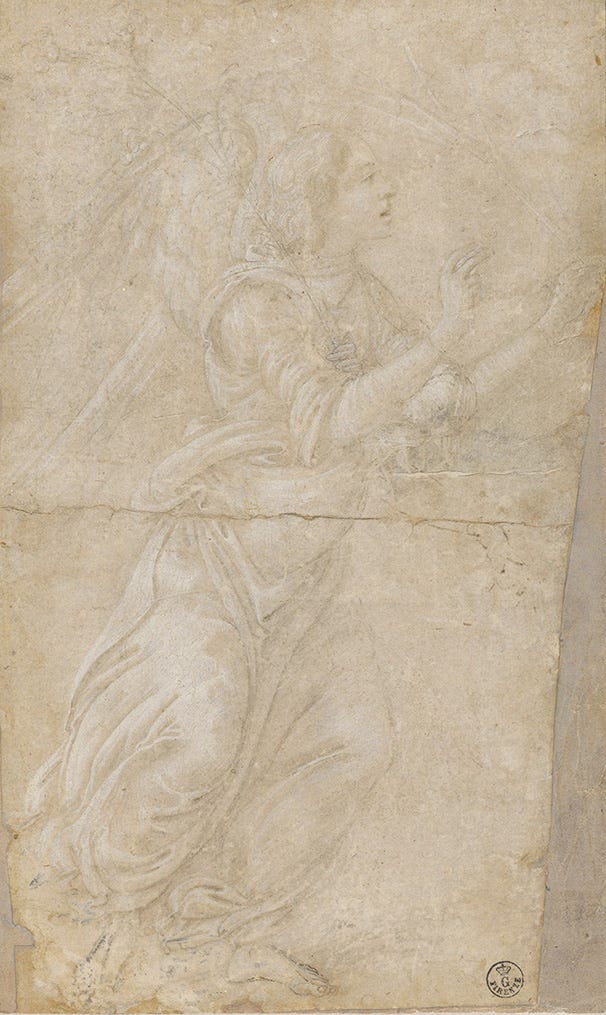

4. Angel of Annunciation

Sandro Botticelli, The Angel of Annunciation, c. 1485–90. Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over metalpoint, heightened with white, on paper tinted with reddish-pink (now discolored), laid down, 9 3/16 x 5 1/2 in. (23.4 x 14 cm). Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, Florence, 200 E. Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi

Sandro Botticelli, The Annunciation (detail), ca. 1485–1493. Tempera on panel, 19 1/2 × 24 3/8 in. (49.5 × 61.9 cm). Lent by Glasgow Life (Glasgow Museums) on behalf of Glasgow City Council, Archibald McLellan Collection, purchased, 1856 © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

During the 19th century, prolonged exposure to light led to the near disappearance of the ink drawing The Angel of Annunciation (1485–90). Upon closer examination, the fine, flowing lines — characteristic of Botticelli’s drawings in the late 1400s — become visible. You can see that Botticelli explored at least four different positions for the angel’s arms. The long stem of the lily can also be seen extending to the sheet’s top-left corner. Within Botticelli’s series of painted Annunciations, the drawing is most similar to the archangel Gabriel in The Annunciation (ca. 1485–1493).

5. Three Young Men

Attributed to Sandro Botticelli, Study for Three Young Men, Two Standing, One Seated (verso), ca. 1465. Metalpoint heightened with white, on pink-mauve prepared paper. 7 7/16 × 10 1/16 in. (18.9 × 25.5 cm). Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille, Pl. 82

Study for Three Young Men shows Botticelli exploring different positions of the human body by using a young workshop assistant as a model. It stands out for the artist’s use of silverpoint, exploratory marks, and thin white lines. The lessons of Botticelli’s teacher, Fra Filippo Lippi (c. 1406 – 1469), are clear — particularly the treatment of white on pink paper. Botticelli’s trademarks can also be seen in the central figure’s defined jawline and elegant stance.

Closing thoughts

Botticelli Drawings brings together rarely seen drawings and paintings for the first time in modern history, and illuminates the creative process behind the artist’s most memorable masterpieces. “I am thrilled to share my new findings,” says Furio Rinaldi. “These new . . . attributions will help lay the groundwork for a fuller understanding of Botticelli’s artistic output and the field of Italian Renaissance art at large.”