George McCalman, James Baldwin, 2021. Image courtesy of Illustrated Black History

“I had a curiosity.” That’s the first line in the introduction to my book Illustrated Black History: Honoring the Iconic and the Unseen. It illuminates my cultural mission statement in making the book, which is a love letter to the accomplishments of the Black community. My curiosity in creating the book was multifaceted: I wanted to document the accomplishments of 145 pioneers of the American experiment. I wanted to share the stories of the Black experience. I wanted to show, yet again, that our history is also a shared one. I wanted to create a defining body of fine art work, but I was also interested in the art of making.

But first, some context. Dr. Carter G. Woodson created what was originally termed Negro History Week in 1926 to center the accomplishments of the community as a path to liberation. Dr. Woodson was the first African American to get his PhD from Harvard, pursuing initiatives to celebrate Black American achievement. Negro History Week evolved into Black History Month in 1976 in the post–civil rights urgency to make the playing field more level.

When I took on the intimidating task of writing, illustrating, and designing this book in 2018, I gave the fine art aspect the most consideration. The portraits were as much of a revolutionary act as the book itself. Portraiture is as important to defining Black history as the history itself. The images matter as much as the words; one doesn’t exist without the other.

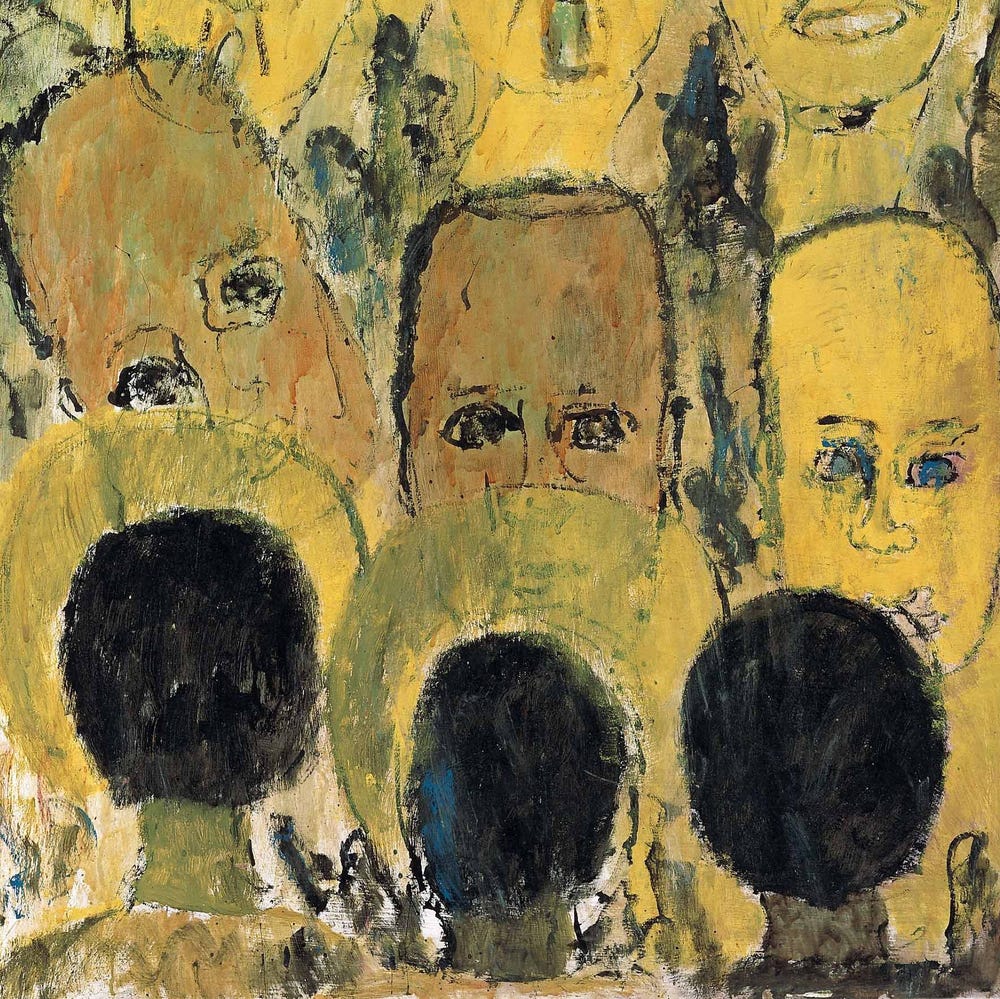

George McCalman, Jean Michel Basquiat, 2021. Image courtesy of Illustrated Black History

It was rare to see portraits of Black people in traditional fine art until the age of photography began in the late 1880s. When we use words such as “traditional” and “classic” in fine art, we are using code. And Black Americans understand that this code, a rendering of history and art, does not include us.

Portraiture is used to define power and permanence. It is a form of cultural propaganda: a way to envision immortality. It bottles up time in a moment. It also conveys historical elitism. In portraiture, we are presenting and preserving the messages of culture.

In our own representation, Black Americans are now defining a counter-narrative to how we have been depicted in the expanse of this nation’s history, a telling of history that is often at our expense. Black portraiture in fine art is in its renaissance. Artists like Toyin Ojih Odutola, Amoako Boafo, and Kehinde Wiley (with his 2023 show at the de Young) are representative of an iconoclastic trend. We are ushering in a new age of art. Beyond institutions (finally) giving the Black arts its due, there is a secondary layer of cultural consideration — the new paradigm is us representing ourselves. In the six years I created art for this book, I never lost sight of my desire to represent each pioneer’s individuality while also honoring the complexity of our country’s history. No two portraits (or accomplishments) are alike.

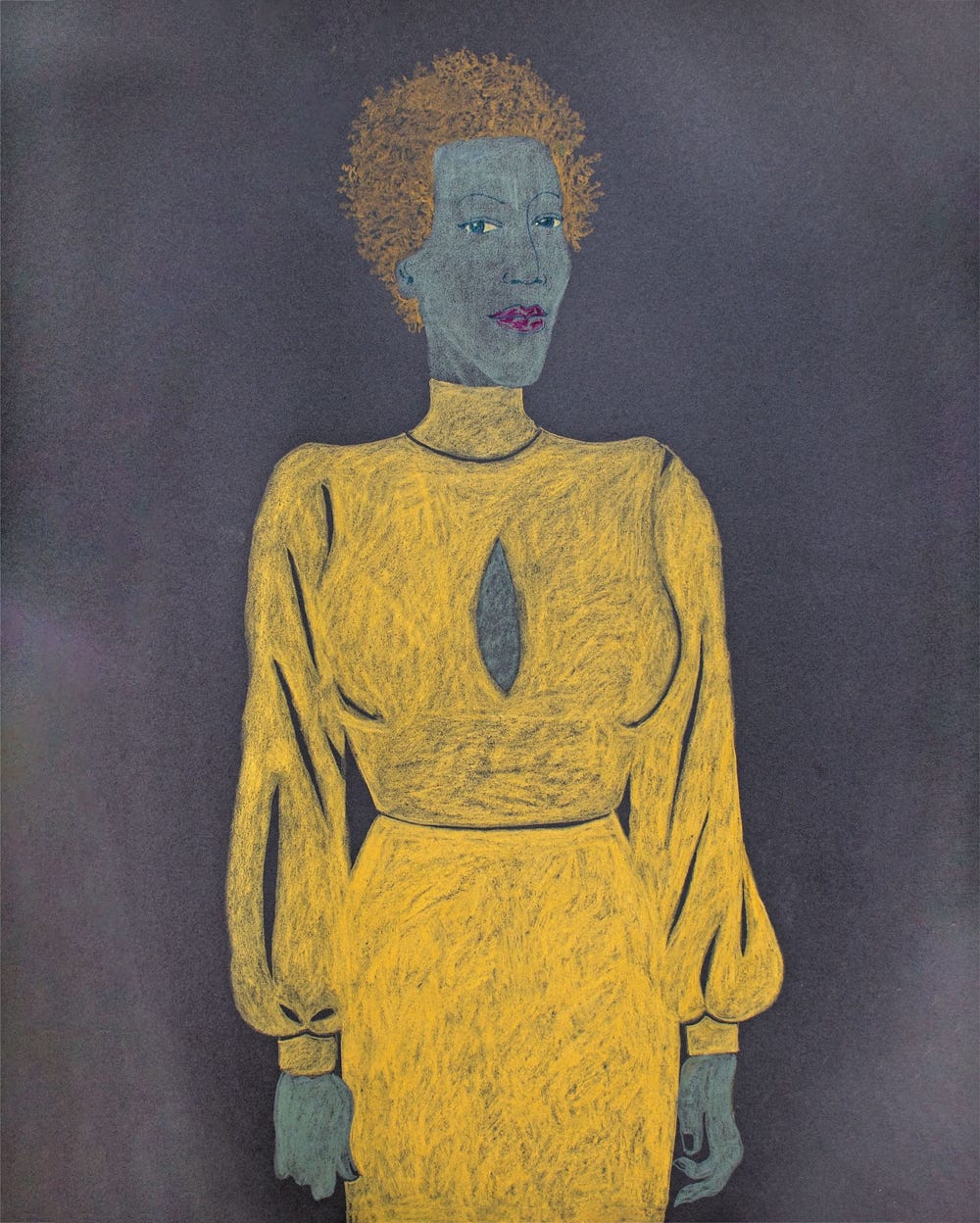

George McCalman, Amy Sherald, 2021. Image courtesy of Illustrated Black History

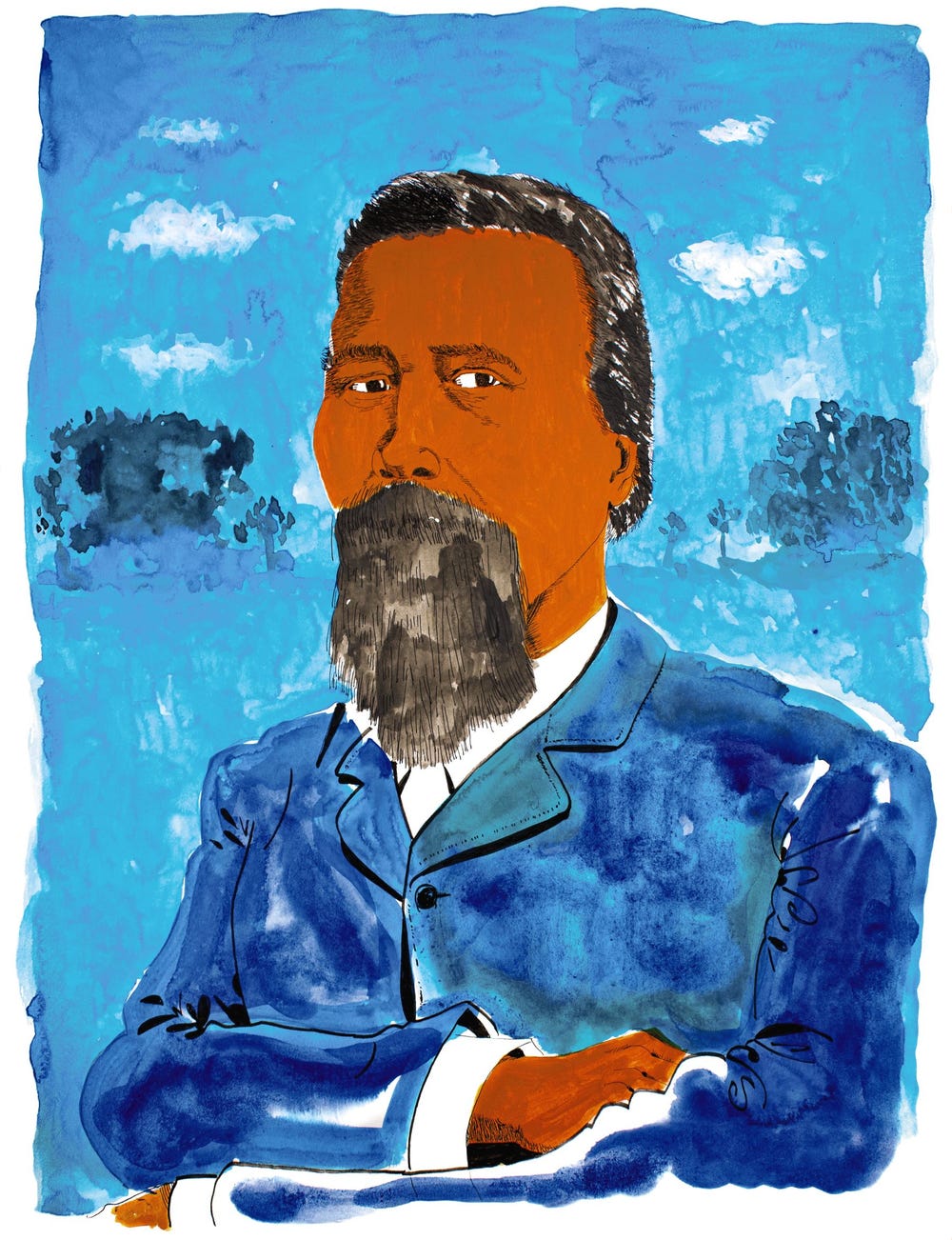

In Illustrated Black History, I adapted the artists’ own styles to define the individuality of each portrait. I looked at the lyrical loneliness of Amy Sherald’s work (also featured at the de Young); her compositional confinement spoke to me as I rendered her portrait. Edward Bannister’s luscious landscapes provided the setting for his portrait, where he sits in a field of fluid paint. I used Jean-Michel Basquiat’s passionate brushwork to define his mercurial personality, the underlayer and the top coat.

George McCalman, Edward Bannister, 2021. Image courtesy of Illustrated Black History

My bias as an artist is toward other artists, which can be seen throughout my book. I selected more pioneering artists than another author might have. I selected more women than men. My philosophy is also a truth: artists are on the front lines of defining American culture, and Black Americans have contributed disproportionately to what we take for granted as American culture.

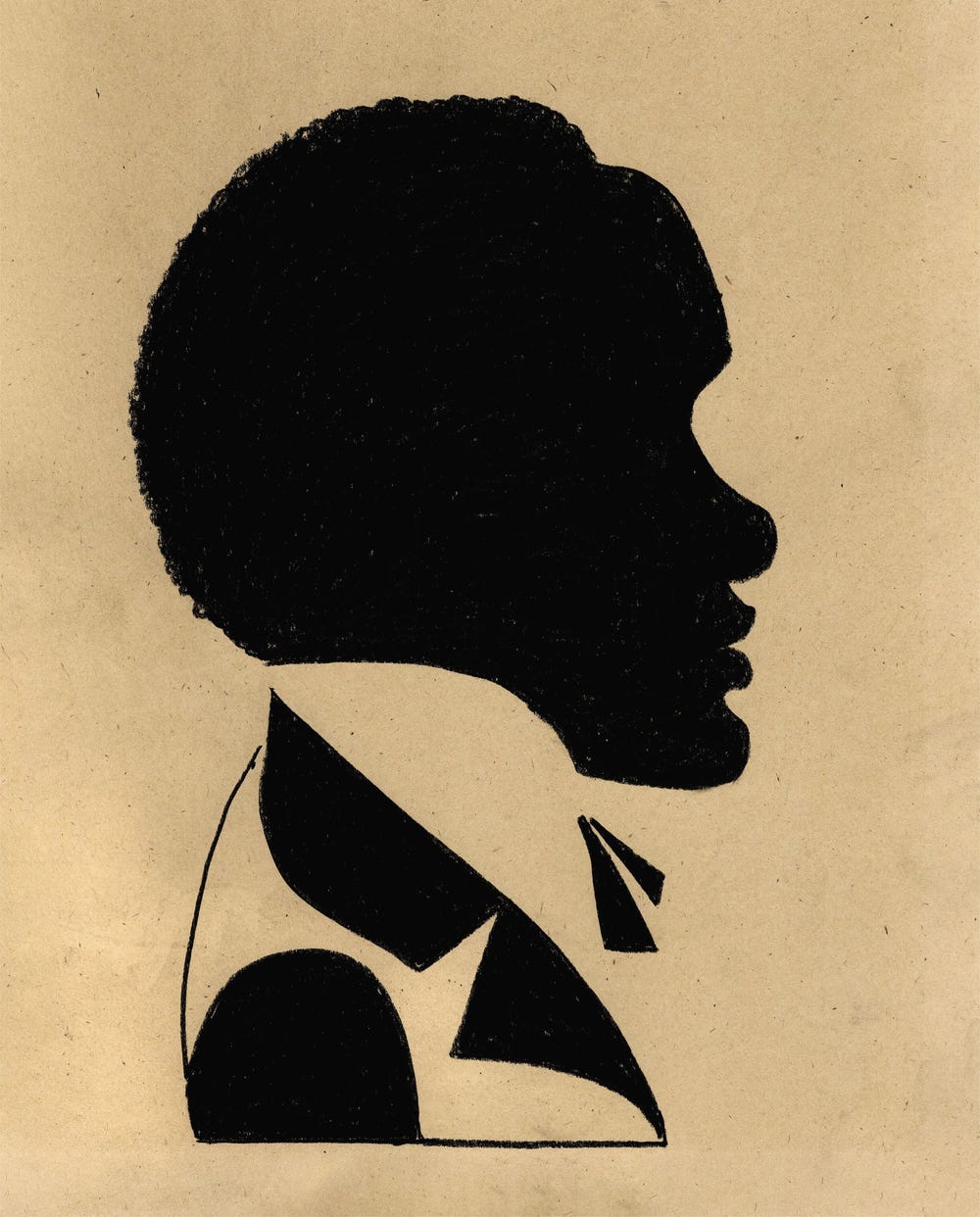

One of the more tragic aspects of making an illustrated guide to Black efforts is that, past a certain point in history, there are no visual references. I made a conscious decision that I wouldn’t be intimidated to create a portrait with no tangible foundation. The dearth of Black representations in visual archives is indicative of the rapacious effort to suppress our place in American culture. In creating the portrait of Cato Alexander, the originator of the cocktail and its culture, I had to call in a more spiritual path.

George McCalman, Cato Alexander, 2021. Image courtesy of Illustrated Black History

My process for creating Illustrated Black History married the extreme ends of rigor and intuition. The writing and design required research and discipline. The making of the art required spiritual intuition and feeling. I drew on the feeling my ancestors worked within me to produce. They asked me to render them in specific ways. I often didn’t know what medium I was going to work in before I sat down. It’s uncomfortable to admit that in this way, but the admission decenters the intellectualism of how fine art is publicly discussed. I sought to create immortality for the emotional truth of the pioneers, as much as their accomplishments. I now see that is my strength as an artist.

America is still in the (sometimes glacial) process of learning our Black American stories. And now we are defining ourselves, to ourselves. As it should be.

Text and illustrations by George McCalman, artist and author of Illustrated Black History: Honoring the Iconic and the Unseen.

Learn more at Illustrated Black History: Talk + Documentary Screening.