Bierstadt to Birk: California Landscape Ideals Versus Realities

By Emma Acker

September 17, 2021

Sandow Birk, Fog over San Quentin State Prison, San Quentin, California (from the Prisonation series), 2001. Oil on canvas, 66 x 90 in (167.6 x 228.6 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, American Art Trust Fund, 2002.7. Photograph Joseph McDonald, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

In Gallery 27 of the de Young museum, visitors will encounter a large-scale and luminous coastal scene. Given the striking visual similarity of the work to many of the nineteenth-century American landscapes exhibited in nearby Gallery 26, viewers may be surprised to learn that the painting was created in the twenty-first century by the contemporary artist Sandow Birk (b. 1962). Although this arresting view of a rocky shore and serene waters readily evokes the picturesque landscapes of Northern California, such as those in nearby Marin County, Birk based the composition of Fog over San Quentin State Prison, San Quentin, California on Beach at Beverly (ca. 1869–1872), a coastal New England scene by the second-generation Hudson River School painter John Frederick Kensett. Artists associated with the Hudson River School, such as Thomas Cole and, later, Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church, used idealized views of the American landscape to symbolize the nation’s aspirations and progress.

Installation view of Gallery 26 at the de Young Museum. Photograph Randy Dodson, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

John Frederick Kensett, Beach at Beverly, ca. 1869/1872. Oil on canvas, 21 15/16 x 34 in (55.8 x 86.4 cm). National Gallery of Art, Gift of Frederick Sturges, Jr., 1978.6.5. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

In the nineteenth century, fueled by the concept of Manifest Destiny, the United States entered a period of aggressive westward territorial expansion. In the paintings, prints, and travel brochures of the era, California typically was represented as a New World Garden of Eden ripe for future settlement. Such artistic boosterism is evident in paintings like Bierstadt’s California Spring (1875), on view in Gallery 26 at the de Young. Replete with cattle grazing peacefully in verdant pastures near the Sacramento River, California Spring presents a romanticized vision of life in the Central Valley, disregarding its harsh realities such as recurrent droughts, flooding, and a landscape depleted by overgrazing. Silhouetted in the distance against a radiant sky, the dome of the Sacramento State Capitol—completed a year before Bierstadt finished the painting—symbolically underscores the region’s importance. Bierstadt painted California Spring in his New York studio in 1875, based on sketches he completed during his 1871 trip to San Francisco, and he exhibited the painting to great acclaim to curious publics in New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia1. Such paintings effectively served as advertisements encouraging westward migration and tourism to California.

Albert Bierstadt, California Spring, 1875. Oil on canvas, 54 1/4 x 84 1/4 in (137.8 x 214 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Presented to the City and County of San Francisco by Gordon Blanding, 1941.6. Photograph Randy Dodson, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Subverting the historically idealized, romanticized perception of the California landscape as unspoilt and paradisal, in Fog over San Quentin State Prison, San Quentin, California Birk included a distant view of San Quentin State Prison—a sprawling 275-acre correctional complex for men located at Point San Quentin in Marin, on the edge of San Francisco Bay. Partially enframing the scene at left is a eucalyptus tree, which Birk added to “create the sense of depth, with the foreground in shade, the middle ground in daylight, and the distance with the prison in the fog.”2 Such spatial dynamics aside, the shadowy presence of the tree—along with the jagged silhouette of the gnarled stump that juts out below—imbues the scene with a sense of foreboding.

Aerial view of San Quentin State Prison, near San Francisco, California. Image: California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation via Wikipedia

Fog over San Quentin State Prison, San Quentin, California belongs to Birk’s 2001 series Prisonation: Visions of California in the 21st Century. In this series of paintings and prints, Birk depicted all of California’s thirty-three state prisons, using the symbolic rhetoric of nineteenth-century landscape artists such as Bierstadt to address the harsh socioeconomic and environmental realities of life in the so-called “Golden State.” Birk’s three-year-long research process for the Prisonation series led him to travel across California, visiting as many of the 33 state prisons as possible—he made it to all but two—and making sketches and taking “sneaky snapshots (using those old cardboard cameras!)” that he would then bring back to his studio. Next, he noted, “I would search through old landscape books to find similar compositions, or compositions that fit what I had seen, or take parts from different compositions and make up my own.” Describing his process for creating Fog over San Quentin State Prison, San Quentin, California, Birk observed,

I had been out to San Quentin and that little neighborhood around it, right by the front gate, and I was looking for a work that was maritime, but also rural, nature, and then I added the fog to [Kensett’s composition]. Like all the works in the series, I felt they worked best when at first glance they seemed to be actual old landscape paintings, but on closer inspection the prison is revealed.3

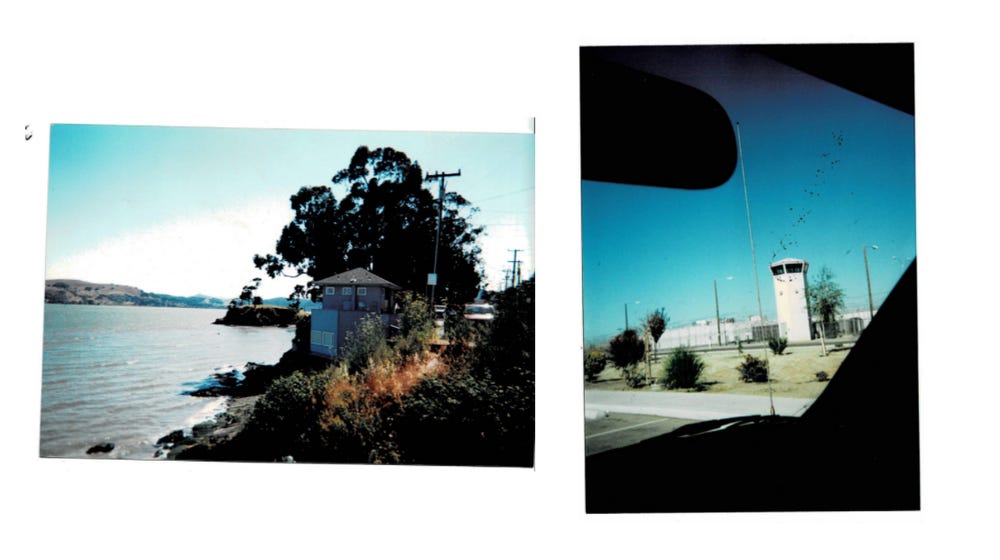

(Left) Sandow Birk, Photograph taken near the entrance to California State Prison San Quentin. © Sandow Birk, courtesy of the artist (Right) Sandow Birk, Photograph taken near California State Prison Solano. © Sandow Birk, courtesy of the artist

Birk’s insertion of an image of a mist-shrouded San Quentin State Prison in what would otherwise be an idyllic scene serves as a grim reminder of the state’s shockingly high incarceration rate, which is the highest in the nation, only slightly behind that of the United States as a whole. Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit organization that “produces cutting-edge research to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization, and then sparks advocacy campaigns to create a more just society,” notes that “241,000 people from California are behind bars,” and “California has an incarceration rate of 581 per 100,000 people (including prisons, jails, immigration detention, and juvenile justice facilities), meaning that it locks up a higher percentage of its people than many wealthy democracies do.”4 As is the case on a national level, the California penal system disproportionately impacts people of color, with incarceration rates that are ten times higher for Black men than they are for white men.5

In addition to perpetuating socioeconomic and racial inequities, prisons are a significant source of environmental hazards, and incarcerated people routinely experience high rates of exposure to toxins, including contaminated water and diseases such as valley fever. Paul Wright, the director of the Human Rights Defense Center, observed, “The EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] has a very long history of ignoring the environmental poisoning of people in prisons and jails in this country.”6 Sparking national outrage, an outbreak in 2020 of COVID-19 at San Quentin State Prison infected more than 2,000 inmates and resulted in 28 deaths.7

Birk described the Prisonation series as being “about landscape painting, what it meant in the past and what I might be able to make it mean, if it could be political.”8 His inspiration for the project came on the heels of a period of prolonged study of “the golden age of American landscape painting . . . promoting the West as this American Eden.” He recalled,

All that was on my mind when one day, in the car, I heard it mentioned that California has the largest percentage of its population in prison than anywhere else on Earth. It was a startling sentence, and I wondered how California had gone from being seen as the Paradise of America, the Eden, where oranges grew on trees, gold was in the ground, the weather is always sunny. . . . and in 150 years it became the most incarcerated people in the world. So that set me off thinking on prisons and deciding to go visit one. And that led to the project. . . . 9

Fog over San Quentin State Prison, San Quentin, California and other works in Birk’s Prisonation series exemplify the power of art to shift our perspective, calling attention to aspects of our environment that we may overlook, take for granted, or deliberately block out. The Hudson River School painters, from whom Birk draws stylistic inspiration, used landscape scenes to express social and political ideas, and ideals, of their era. In a trenchant contemporary twist on this approach, in the Prisonation series Birk visualized the disturbing evidence of human encroachment on a landscape that, in the artist’s words, “is fast becoming . . . [one of] imprisonment, confinement, and despair where it had once symbolized freedom, space, and hope.”10

Works Cited

1 Bierstadt traveled to California four times; in 1871, on his second trip, he stayed in San Francisco for two years and three months.

2 Sandow Birk, email to the author, August 3, 2021.

3 Sandow Birk, email to the author, June 22, 2021.

4 https://www.prisonpolicy.org/profiles/CA.html For example, California’s incarceration rate is significantly higher than that of the entire United Kingdom.

5 “In 2017, the year of most recent data, 28.5% of the state’s male prisoners were African American—compared to just 5.6% of the state’s adult male residents. The imprisonment rate for African American men is 4,236 per 100,000 people—ten times the imprisonment rate for white men, which is 422 per 100,000.” (https://www.ppic.org/publication/californias-prison-population/)

6 https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/05/behind-bars-on-polluted-land/484202/

8 Sandow Birk, email to the author, June 22, 2021.

9 Ibid.

10 Sandow Birk, quoted in Incarcerated: Visions of California in the 21st Century (San Francisco: Last Gasp, 2001)

Text by Emma Acker, associate curator, American Art.

Learn more about the American art collection.